Stonewall 50 – Episode 1 – Prelude to a Riot

Matchbook cover advertising Bonnie’s Stonewall Inn, c. 1940s. Credit: From the collection of Tom Bernardin.

Matchbook cover advertising Bonnie’s Stonewall Inn, c. 1940s. Credit: From the collection of Tom Bernardin.Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: Context is everything. When I first started researching the Making Gay History book (originally called Making History), I thought that the Stonewall uprising was a singular event. Gay people fought back against police oppression and the gay rights movement was born. No before. Just a riot and the rest was history.

But I quickly discovered that Stonewall had rich, complex, fraught, compelling, exciting, and inspirational backstory. And that’s the story we cover in this first of four episodes marking the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising.

Unlike our usual format of featuring one or two voices in each episode, in “Prelude to a Riot” we share multiple voices to set the stage for that now-iconic night on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village when LGBTQ people said “Enough!” in a voice so loud and angry that it was the police who ran from us and not the other way around.

———

If you’d like a primer on Stonewall, here is a handy factsheet that Making Gay History co-produced. The final page has more resources if you’d like to dig a bit deeper. For even more Stonewall resources, check out Marc Stein’s The Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History.

To find out more about some of the people featured in this episode and the times in which they lived, check out the following Making Gay History episodes and the accompanying episode notes: Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen (part 1 and part 2), Randy Wicker and Marsha P. Johnson, Ernestine Eckstein, and Sylvia Rivera (part 1 and part 2). Craig Rodwell will be featured more extensively in upcoming episodes, but he also makes an appearance in our episode about Dick Leitsch, with whom Craig Rodwell was in a relationship during their early days at Mattachine.

To learn more about pre-Stonewall demonstrations and confrontations with the police, read Denio Lourenco’s VICE article here.

Many of our previous episodes include interviews with LGBTQ trailblazers who became active in the movement pre-Stonewall. To learn more about the founders of some of the early U.S. homophile organizations, have a listen to our episodes with Harry Hay, founder of the Mattachine Society; Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, cofounders of the Daughters of Bilitis; and Dorr Legg, Martin Block, and Jim Kepner, who spearheaded ONE.

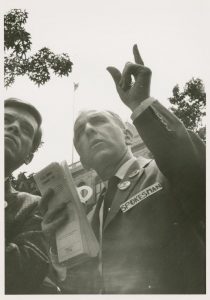

Craig Rodwell mentions an altercation between him and Frank Kameny at one of the annual Reminder Day pickets at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, which were held from 1965 to 1969. In the short documentary The Second Largest Minority, shot at the 1968 picket by Lilli Vincenz, you can see Craig Rodwell smiling at 1:23 and hear Frank Kameny starting at 1:53.

Jay Shockley and Amanda Davis, who take us on a tour of Greenwich Village in the episode, are both with the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, which maintains a terrific website where you can get more information about some of the gay bars and clubs (and much more) mentioned in the episode.

If you’d like to hear more of The New Symposium, the groundbreaking gay-interest radio program that aired on WBAI in the late 1960s, go here for an astonishingly frank 1968 conversation between host Charles Pitts and a gay hustler.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus: And let’s see if I’m picking up. I’m picking up.

Frank Kameny: Is it working?

EM: Yeah.

FK: All right.

EM: The question was about the movement, when it got started. Things got cooking…

FK: In ’51, with the famous meeting in a closed room in Los Angeles, which has been so often described. And I’m sure it has cropped up…

EM: June 3, 1989. At the home of Frank Kameny in Washington, DC.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

It’s almost exactly 30 years since I sat down to interview the proudly radical gay rights pioneer Frank Kameny and he tried to answer that not-so-simple question: When did it all begin?

And there’s another anniversary this June that’s being a bit more widely celebrated. The 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.

You’ll hear some people—not me, other people—say that Stonewall was the place where it all began. Not true. Queer resistance wasn’t invented in June 1969. But what happened at Stonewall did mark a key turning point in our history—one of those moments that draws a line between before and after.

This first episode of our Stonewall 50 season is about the before. So we’re going to take a quick tour through American LGBTQ history pre-Stonewall (and if you want more—we did 11 episodes on this last season).

The 1950s had seen anti-gay oppression in the U.S. intensify. Thousands of gay people were fired from their government jobs during the Lavender Scare, the military went on a witch hunt to root out homosexual service members, and police crackdowns on gay bars around the country were on the rise—all at a time when the gay rights movement was in its infancy.

And that’s why I want to take you back to Frank Kameny’s home in Washington, D.C. Frank stepped out of the shadows and fought back against discrimination when he was fired from his government job for being gay. He became a pivotal figure in the movement.

Here’s the scene: It’s 30 years ago. I’m 30. Frank’s in his mid-60s and full of vim and vinegar. We’re surrounded by piles of files in his dusty, jam-packed office and Frank’s explaining to me the state of the movement in the mid-1950s…

———

FK: The entire movement in the United States was only three or four organizations, most of which were chapters of Mattachine. DOB had just started. ONE, Incorporated, in Los Angeles was the other one.

———

EM Narration: And I had the audacity to suggest there were several dozen people fighting the good fight.

———

EM: … several dozen people…

FK: Several dozen? Several people! There weren’t several dozen in the movement! You’re in 1957! Not ’67 or ’77 or ’87!

EM: So we’re talking about a few people.

FK: Yes. A person or two.

EM: Could we count them on two hands, all the people in the…?

FK: I think you could count them on one hand. Well, that overstates. That’s hyperbole. But yes.

The movement of those days was a very unassertive, apologetic, defensive kind of structure. Not taking strong positions. Giving a hearing to everybody and saying, “All views must be heard, even those which were most harshly and viciously condemnatory. As long as it dealt with homosexuality, they must be given a fair hearing.” Drivel! We were sick. We were sinners. We were perverts. You have your long litany of pejoratives. There was absolutely nothing whatsoever which anybody heard at any time anywhere at all which was other than negative! Nothing! And so the movement, predictably, responded accordingly. And that was the nature of the movement.

———

EM Narration: You’ll hear echoes of Frank Kameny in what Barbara Gittings had to say when I talked to her in 1989. Barbara and Frank were kindred spirits in what was then known as the homophile movement.

While Frank headed up the Washington, DC, Mattachine Society, Barbara was the founding president of New York City’s chapter of the lesbian group the Daughters of Bilitis.

———

Barbara Gittings: We were considered sick, so the sickness label infected everything that we said and did and made it very difficult for us to have any credibility for anything we said for ourselves. We were considered sinful so we had to start dialogue with the churches. And we were considered criminal. So we had to deal with the sodomy laws and by extension with any of the laws that controlled our lives or did not give us the freedom that we needed.

———

EM Narration: Barbara met Kay Lahusen—her partner in life and activism—in 1961. And together they rejected society’s prescriptions for homosexuals.

———

Kay Lahusen: The going theory at the time was that you were sick and you should go to the doctor and get turned around.

EM: What did the therapist tell them at this time?

KL: Usually trying to cure them.

EM: Fix them.

KL: Uh-huh. Deep analysis. Find out what went wrong in your childhood and so forth. Not too many people just, you know, thought for themselves and thought, you know, this is a crock of shit. It was chic to be going to the therapist. Anybody with any income at all went to the therapist to get straightened out.

EM: Literally.

KL: Yes.

———

EM Narration: But as the 1950s waned and the ’60s dawned, attitudes had started to shift. A handful of psychologists were questioning whether the sickness label was anything more than a myth. And as the hysteria of the Red Scare eased, so did the witch hunts of the concurrent Lavender Scare.

The early 1960s gave way to the mid-’60s and a time of upheaval and unrest, from Black civil rights and the anti-war movement to women’s rights, assassinations, sexual liberation, and inner city riots. Confrontations with the police on college campuses and at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago filled television screens on the nightly news.

The waves of activism sweeping the country were felt by local gay rights groups—and they began organizing on a national level.

Frank Kameny recalls a breakthrough meeting of homophile organizations in New York City in 1965.

———

FK: We looked around and, to our amazement, there were representatives from 16 gay organizations. We honestly didn’t realize there were that many gay groups in the country. And decided, this is wonderful. We have to have a national meeting. So we had a February meeting, we set it for February ’66, in Kansas City, because Kansas City was equally inaccessible to all the organizations that then existed and didn’t favor anybody. By February of ’66, the 16 had gone up to 20.

———

EM Narration: Alongside the growing numbers of groups and activists, there was a growing push for visibility.

Randy Wicker was a 24-year-old gay rights organizer living in New York City who formed a one-man action committee and marched into community radio station WBAI in 1962 to demand representation.

———

Randy Wicker: A lot of people think I was terribly idealistic. I was. But if I didn’t do it, no one else would. I mean, on BAI, they had these psychiatrists that were making all these stupid statements about homosexuals. None of them knew a damn thing what they were talking about. I mean just nonsense. So I went to BAI and I said, “Why do you have these jerks discussing homosexuals? I can get a group of gay people together that’ll tell you more about homo–, know more about homosexuality, that lived the life, than these so-called experts.”

I never heard such garbage in my life, because, you know, they’re saying they could change people or cure people or, I mean, every time I turned on the radio, it was one of these creep jerks that are out there looking for guilt-ridden homosexuals to pay them $50 an hour, per hour, for therapy to cure them, and I was outraged by this. So I began plugging into the network, saying, “If you’re going to have a show on homosexuality, please know we’re available.” So they would start including us on panels, especially on the radio. And then I was on every major show.

———

EM Narration: In addition to early radio and TV appearances, activists staged the first public demonstrations challenging discrimination in employment and the military. And Randy Wicker led the very first public picket in 1964. More protests followed in 1965—at the White House, the Pentagon, and then the first annual July 4 picket outside Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. It was called Reminder Day, to remind all Americans that gay people were being denied their constitutional rights.

Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen were at the Annual Reminders. Interviewing them back in 1989, I asked them if those early pickets were thrilling—apologies for being a little off mic.

———

EM: Was that thrilling?

BG and KL: Oh, yes!

BG: You were really… You know, you knew you were doing something momentous. And people would stare at you. They had never seen self-declared homosexuals parading with signs.

KL: And there were like 50 in the line in front of the White House…

BG: Fifty! It wasn’t that many. It was 26.

KL: Well, there was a second picket that had a little bit more people, I believe.

BG: Not many.

KL: But, um… And suits and ties, and, you know, dresses for the women, and all that.

BG: That was one of the few things we agreed on at the time, all the groups. We hashed it out and decided that we were the bearers of a message and in order not to attract attention to ourselves but to get to the message we’d have to blend into the landscape so we would look unexceptional.

KL: Right.

———

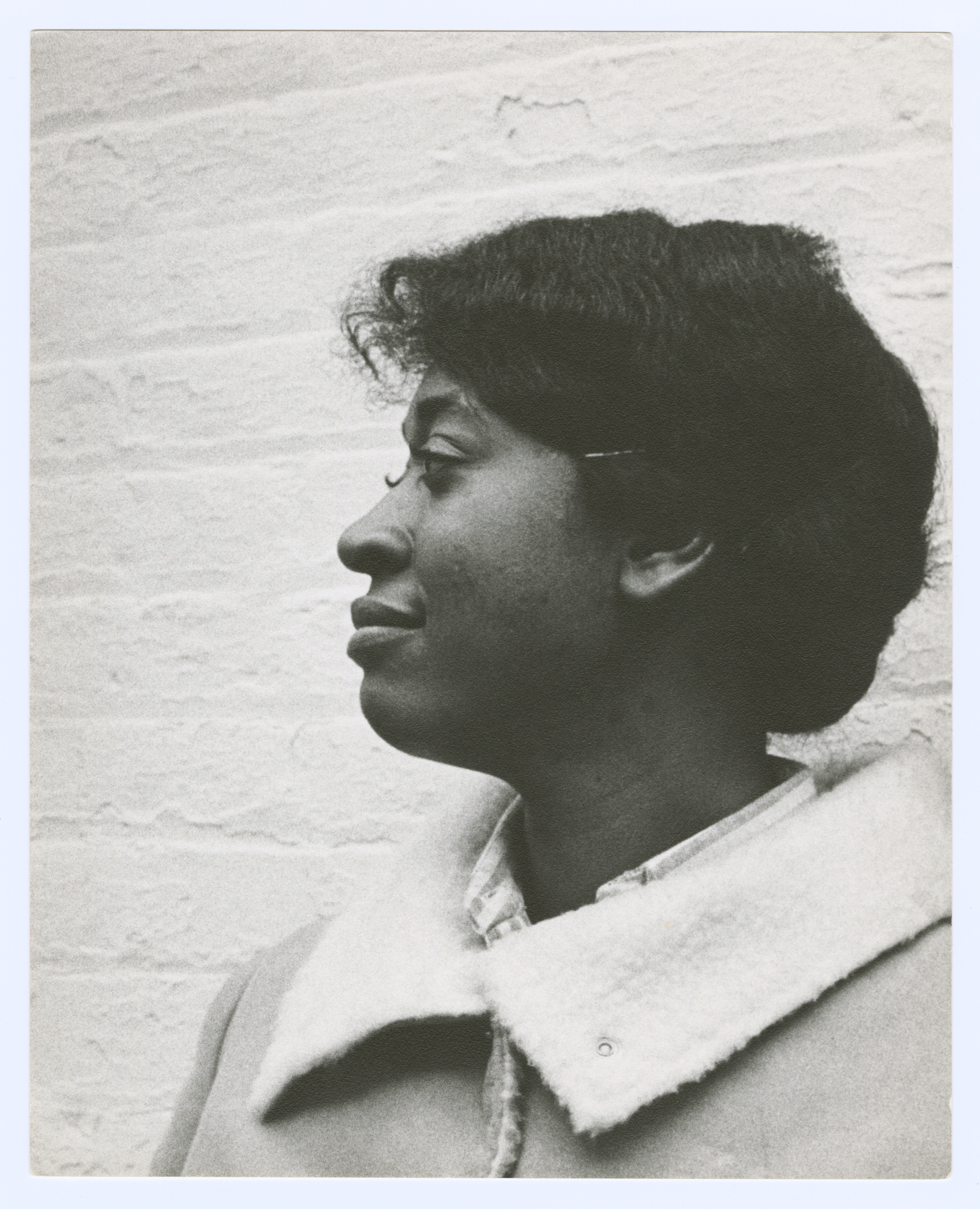

EM Narration: Ernestine Eckstein walked those early picket lines, too. She was the vice president of the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis, and she brought her experience with the Black civil rights movement to the homophile movement. But when Barbara and Kay interviewed her in 1965, Ernestine told them that polite picketing might not be enough anymore.

———

KL: Do you believe in forms of civil disobedience for our movement at this time or in the future?

Ernestine Eckstein: Picketing, I regard it as very, almost a conservative activity now. I mean, sit-ins, you know, and that kind of thing are the thing. All of this is the educational process of calling attention to the unjustness of the situation, which is the same thing the Negro did.

———

EM Narration: Ernestine wasn’t the only activist feeling weighed down by what they considered the homophile movement’s cautious approach.

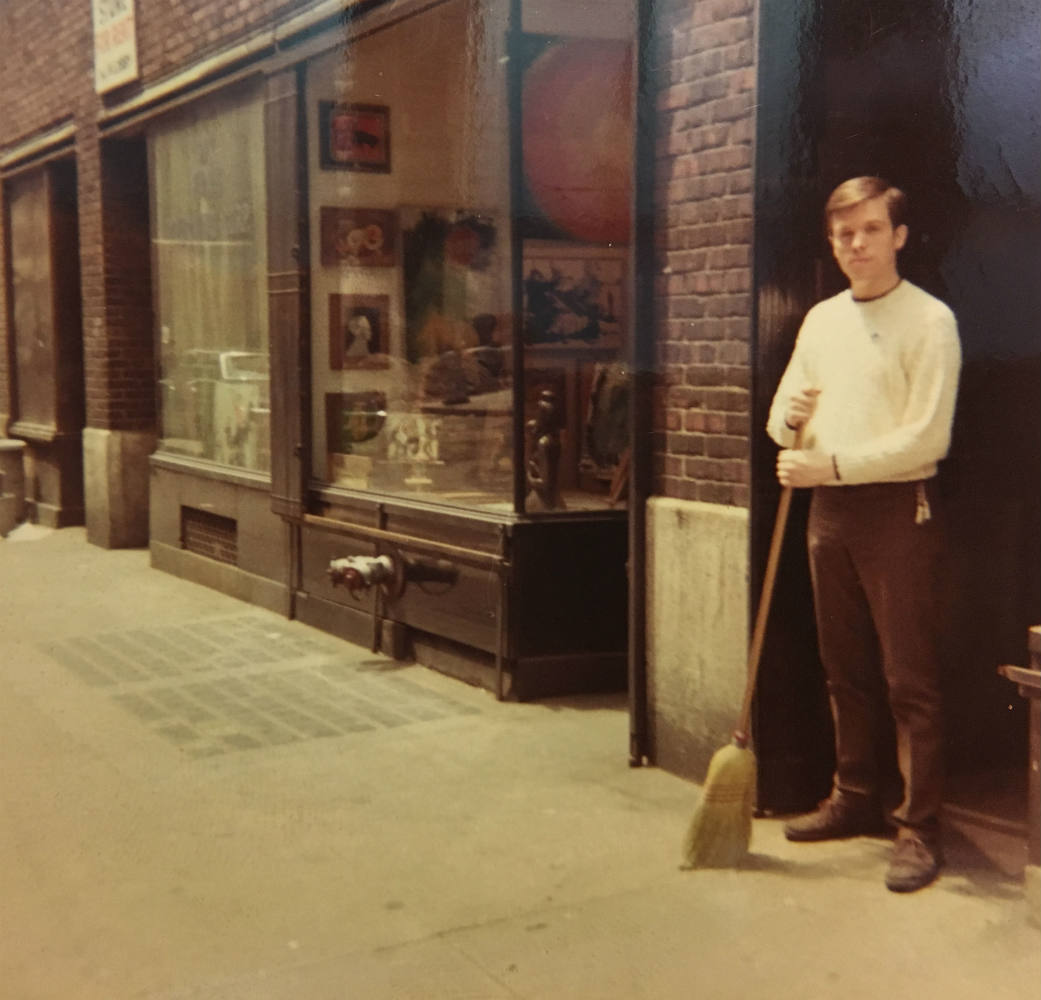

Craig Rodwell was a troublemaker who burst out of the closet at a young age. You’re going to hear from Craig a lot this season. Pick a significant moment in gay history in the 1960s or ’70s, Craig was there.

In the late 1950s in Chicago, Craig tried to join the Mattachine Society. But he was turned away because he was too young. Both the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis required members to be 21 or older, for fear of being accused of corrupting minors.

So Craig saved up his school bus fare and asked for cash for Christmas and birthdays so he could move to New York City and find “his people.” Teenage Craig had read about the homosexuals who hung out in a mysterious place he called “Green-witch Village.” He didn’t know it was pronounced “Gren-itch,” because he’d only ever read it.

———

Craig Rodwell: So I came to New York in January of ’59, ostensibly to study ballet, which I’d studied since I was seven. And I got a scholarship with the New York City Ballet Company. I wanted to be more involved in, not only in gay life, but in movement work.

———

EM Narration: That’s Craig, speaking almost 50 years ago in a treasure of an interview we found from 1970. Kay Lahusen is asking the questions. She recorded the interview as research for her book The Gay Crusaders. Craig told her that when he made it to New York, he headed straight for the Mattachine office. He was 18 years old.

———

CR: I went to Mattachine immediately. But, again, I couldn’t really work with them because I wasn’t 21. So I subscribed to the newsletter and went to meetings and what have you.

KL: Did you tell them about it at ballet school?

CR: Well, all of my fellow students were gay and, sure, I used to take them to meetings or try to get them to go to meetings.

KL: Did they dig it?

CR: No. I would get a few of them to go, ’cause back then no one really, especially young people, didn’t think of homophile organizations as being anything to gain your rights particularly. They were more socializing, hearing speakers on psychology and psychiatry, religion, things like that.

———

EM Narration: Despite his ballet school friends’ reluctance to take part, Craig formally joined the Mattachine Society after his 21st birthday in October 1961. He set about trying to modernize Mattachine from the inside. But as the decade wore on, Craig became more and more frustrated with the movement’s self-imposed restrictions.

———

CR: To me, suits and ties as a uniform are part of the larger heterosexual culture. It’s part of how society tries to define us as men and women. You know, men wear this and women wear that.

———

EM Narration: Craig and Ernestine were on one side of a generational rift that was starting to open up between activists who had previously been perceived as radicals—Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings, Kay Lahusen—and a younger generation coming of age in the late 1960s who were losing patience with buttoned-up homophile leaders—a conflict that broke out into the open at one of the Reminder Day protests.

———

CR: Kay and I had an altercation on this, which I’m sure you remember. Two women were holding hands on the line, and Frank went up to them and told them to stop, which infuriated me, as you can well remember. I just hit the ceiling, so I went and organized three or four couples to hold hands. And it created a mini-furor within the thing to the point where I barged at a reporter and had a verbal fight with Frank, called him an Auntie Tom, I think.

———

EM Narration: That’s the first time I’ve heard the term “Auntie Tom.” And you just heard Frank Kameny a few minutes ago. Can you imagine that moment? I wouldn’t dare. But I’m not Craig Rodwell.

Back to Kay Lahusen’s interview with Craig, and you can hear that friction between the generations.

———

KL: Well, his idea was that you don’t call attention to yourself as an individual, that the issues must be pushed. And the person is subservient to the issues.

CR: Yeah, but to me, especially what always has been one of the main issues, if not the main issue, you know, in my own head and I’m sure a lot of other people, was that homosexuality is just as viable a way of life as heterosexuality.

KL: But we weren’t picketing for a way of life at the time. We were picketing for fair employment and all that shit.

———

EM Narration: While the homophile organizations were blazing a trail with public demonstrations—albeit dressing conservatively, picketing in a straight line, and asking for employment protections—LGBTQ people also faced routine harassment from the police, entrapment, and physical abuse at the hands of the authorities in cities and towns around the U.S.

For a trans woman of color like Marsha P. Johnson, who survived as best she could on the streets of New York City, that oppression meant the constant threat of arrest. When I interviewed her in 1989, Marsha told me that the police picked her up countless times when she worked 42nd Street in the mid-1960s.

———

Marsha P. Johnson: And every time we go, you know, that going out to hustle all the time, they would just get us and tell us we were under arrest. Yeah, they’d say, “All youse drag queens are under arrest.” So we, you know, it was just for wearing a little bit of makeup down 42nd Street. That was like in 1960, when I first came here was in 1963.

———

EM Narration: Back then, if you were wearing fewer than three items of clothing that aligned with your legally assigned gender, you could be arrested. That gave the police broad authority to harass and humiliate people who didn’t conform to the gender norms of the time.

On October 26, 1962, dozens of attendees who were dressed in drag at the National Variety Artists’ Exotic Carnival and Ball held at New York City’s Manhattan Center were arrested on charges of masquerading and indecent exposure. Here a policeman leads two men in drag by the arm. Credit: Getty Images/Bettmann.

———

Sylvia Rivera: You want me to tell you how many times I went to jail?

EM: How many times did you go to jail?

SR: [Laughs.]

———

EM Narration: This is Sylvia Rivera, who later founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries with Marsha. I interviewed her, too, back in 1989.

———

SR: Oh, when I was growing up, if you walked down 42nd Street and even looked like a faggot, you were going to jail.

EM: So you went to jail a few times.

SR: Oh, I went to jail a lot of times.

EM: Fifty times? A hundred times? Two hundred times?

SR: About 200 times.

EM: What were you in jail for?

SR: Prostitution, you know, bullshit loitering. Back then when I first started out, I was in women’s clothes. It was what they call scare drag.

EM: Scare drag? What is scare drag?

SR: What I’m wearing right now. You don’t have the tits on or anything. You just have a little makeup on, you have your hair out, you got women’s clothing on. But every time that I used to go in front of a judge—”upper head female impersonation.”

EM: That was the charge.

SR: Yeah.

———

EM Narration: The harassment wasn’t confined to 42nd Street and the street queens—although they doubtless bore the brunt of it. Craig Rodwell told me Greenwich Village, the so-called gay ghetto, was not exempt.

———

CR: I mean, back then, in cruising areas, you couldn’t stand still. Like on Greenwich Avenue, which was a major cruising area at the time. I mean, every night there would be hundreds of gay guys sitting on cars and stoops. But if a cop came along, everybody’d get up and start walking. And if you didn’t, they’d come up and they’d poke you.

EM: What was everyone afraid of?

CR: Being beaten or arrested and I suppose ultimately of being publicly identified as a homosexual.

EM: What would that mean?

CR: Perhaps loss of job or… In other cities, when they would raid gay bars, the papers would publish the name and address and where they worked of the people who were arrested. On the front page of the papers the next day, I mean, like they were mass murderers or something.

———

EM Narration: And Greenwich Village is where we’re headed next.

———

Jay Shockley: My name’s Jay Shockley. I’m one of the founders and co-directors…

Amanda Davis: And I’m Amanda Davis, the project manager…

JS: … with the New York City LGBT Historic Sites Project.

———

EM Narration: I’m on a tour of Greenwich Village with my favorite experts on gay-related sites in New York City. We’re standing on the corner where Christopher Street, Greenwich Avenue, and 6th Avenue meet.

———

JS: On this corner, across the street, where there’s now a garden, was an enormous art deco prison that was the Women’s House of Detention. Actually, it was the first all-women’s prison in New York City. In terms of the gay community, it was famous and infamous because if women, if lesbians were in bars that were raided, they were taken to this house of detention. And it became notorious in the Village. There were lesbians on the street that were shouting to their girlfriends. The street residents of Greenwich Village had a long campaign to have it demolished because they didn’t like that street interaction and the constant screaming.

AD: Yeah, and actually Joan Nestle, who went on to co-found the Lesbian Herstory Archives, famously said that it was called “the Country Club” by many lesbians who were arrested and put there at that time.

EM: So this was even going on in 1968-69 when if a women’s bar was raided, the women would be carted to the Women’s House of Detention.

JS: This is such a major intersection. The PATH station coming in from New Jersey is just across the street from there. The northern end of the Washington Square subway stop on the, is just south of 8th Street. So this is a major focal point for people getting out of subways. If you continued west from this site, then you’d start hitting bars that were all along Christopher Street.

EM: Stonewall wasn’t the only bar…

AD: As far as lesbian bars, there was the Pony Stable Inn on West 4th Street right off of Madison, uh, Washington Square Park. There was the Sea Colony, which was very popular, on 8th Avenue just north of here, and the Bagatelle on University Place. These were all in existence. As far as gay bars, gay male bars…

JS: Yeah, Julius’, which is just one block away from here around the corner, was a very popular gay bar and a very important bar. Also just across 7th Avenue South on Grove Street, Marie’s Crisis was always a popular piano bar. There definitely were places on Greenwich Avenue. Some of them may not have been “bar bars.” They may have been cafes that may or may not have had liquor licenses.

EM: I’m looking down the street now and this is, I don’t see gay people parading, gay men parading up and down the street. From what I understand, both Greenwich Avenue and Christopher Street were major points at which gay men in particular met.

JS: Prior to Stonewall actually happening, Greenwich Avenue was, was the main cruising spot all the way from Christopher Street up to 7th Avenue up there. Now on the other hand, I’ll qualify that to an extent, because people were always going down Christopher Street, down to the piers, and men looking for other men, sex, whatever, way back there were waterfront-oriented bars, when those were the steamship piers. So there always was street traffic going all the way down there.

EM: For people who don’t know, what was cruising? I mean cruising isn’t what it used to be because so many people now meet online, but in the olden days, when you and I were young, what was cruising?

JS: Well, cruising is different in different locations. I mean, everybody, if you’ve seen any movies that are set in the ’50s, American movies, in small towns people were cruising in cars. They’re going to the courthouse square or whatever else. All young people and all teenagers are looking to meet other similar-age people, whether it’s just to hang out with or socialize or whatever. In terms of New York and the LGBT community specifically, cruising was either lingering in doorways or on street corners, or walking up and down the street looking to meet other men. For socializing or for sex or anywhere in between or beyond.

AD: Thank you. I’m glad the rain held out.

EM: Yes, we’re lucky.

———

Charles Pitts: The program is “The New Symposium.” My name is Charles Pitts and the members of “The New Symposium” are…

Dale Tyson: Dale Tyson.

Kermit Lamb: Kermit Lamb.

CR: Craig Rodwell.

Leon Smith: Leon Smith.

Louis Maletta: Louis Maletta.

CP: I should mention that Craig Rodwell is visiting us tonight to discuss his, discuss the subject, which is cruising areas.

———

EM Narration: This is the WBAI show “The New Symposium.” This edition of the show was broadcast in August 1968. Things had moved on since Randy Wicker’s first appearance on WBAI back in 1962 and by now there was a whole show dedicated to gay life. As you just heard, the main focus of this broadcast was cruising.

But first…

———

CP: News and reviews.

———

EM Narration: The show followed a simple format. At the top of the show, news and reviews, when the assembled panel—almost always entirely composed of gay men—would scan the newspapers and tease out stories affecting the gay community—and they give us a unique window into gay life in New York City at the time. Here’s Craig Rodwell explaining a story he found, about an incident at the docks on the far west side of Greenwich Village.

———

CR: One morning last week at 3:30 a.m. a Transit Authority policeman just happened to be passing by them, the infamous docks at the foot of Christopher Street, on his way home. And there he observed three men leaving the back of a truck.

———

EM Narration: The trucks were another fixture of gay life in the Village, a place where men went to have sex in the back of freight trucks parked overnight underneath the elevated West Side Highway that ran past the mostly abandoned shipping piers.

———

CR: And when the cop went to question the three men what they were doing in the back of the truck. And as the story goes in the Times, one of these three men pulled a screwdriver, whereupon the cop pulled a gun and killed the man and the other two men fled. There’s much more to this story, I’m sure, than meets the eye. The two men that fled, we would appreciate it very much if you would contact Charles Pitts or Baird Searles here at WBAI. Your identity will be protected. We would like to know the story of really what happened.

Unidentifiable Speaker: It does sound a little suspicious.

CR: Well, I think the most incredible part of the story is that this Transit Authority patrolman just happened to pass by the docks on his way home at 3:30 in the morning. It isn’t a place you just happen to pass by, I don’t care where your home is, unless you live in a houseboat at the foot of Christopher Street.

———

EM Narration: And now Kermit Lamb pulls out an item from the “Scenes” column in the Village Voice, the now defunct alternative downtown weekly newspaper.

———

KL: Howard Smith in “Scenes” column had happened to notice in last week’s Voice that there was an awful lot of cruising or homosexual activity at the corner of 6th and 8th in the Village. A lot of the rest of us have noticed it for years! Apparently, according to Mr. Smith, it’s a game among some people down there to figure out which are the boys and which are the girls, and that’s no news either.

———

EM Narration: They also comment on police raids at the popular gay summer destination of Fire Island before turning to the main discussion.

———

KL: The subject tonight is meeting places, cruising spots.

———

EM Narration: Buckle up and get ready for a whistle-stop tour of gay New York in 1968.

———

KL: That doesn’t necessarily mean bars. It includes a lot of things. I suppose you can cover in just a few sentences a lot of the public places, such as certain areas of 3rd Avenue, which in the 50s is more commercial, and farther up 3rd Avenue in the 60s is, is less so. Central Park West, Times Square, many areas of the Village, and small local spots like Brooklyn Heights’ Promenade. I have some friends who live near Columbia who cruise a lot along the park along the Riverside Drive.

There’s a little postage stamp park at the end of 57th and Sutton Place. The only thing there is you almost have to have a dog to cruise there because everybody cruises with their dogs. You have to discuss vet fees, various things, you know. And then of course there’s always the kind of people who will do subway johns, tearooms, Grand Central, Port Authority, all of that kind of public thing.

Unidentifiable Speaker: There’s a one-way mirror in the urinals at Grand Central. And the next time you’re in Grand Central, just take…

Unidentifiable Speaker: Wave!

Unidentifiable Speaker: Just glance up and give a wave to whomever is behind there or whatever is behind there, if it’s a camera.

Unidentifiable Speaker: More recently I had the opportunity of taking some friends from Michigan around New York, visiting several gay bars. I thought to myself that it’d be interesting if we would plan out several routes, you know, to give a potpourri to people in the city that they could take. So I thought of, I started them at the Stonewall to give them the younger set, plus the dancing boys, I thought, was kind of cute, they had never seen anything and they were a little taken aback when they walked in. And from there we walked down Christopher Street to the next block over, and the nice thing about this is that you don’t have to walk too far without getting into another place and another kind of clientele. And on the corner of, what is it, Christopher and Hudson? Right down from the Theatre de Lys. There’s another bar…

Multiple Speakers: Danny’s.

Unidentifiable Speaker: Just a little below there, yeah.

Unidentifiable Speaker: That’s an interesting group of people. And then we went from there to Keller’s to kind of get the leather, and we ended up at the docks. So they had a full swing of what we’d call from one end to the other of the gay life and the gay bars in New York City.

———

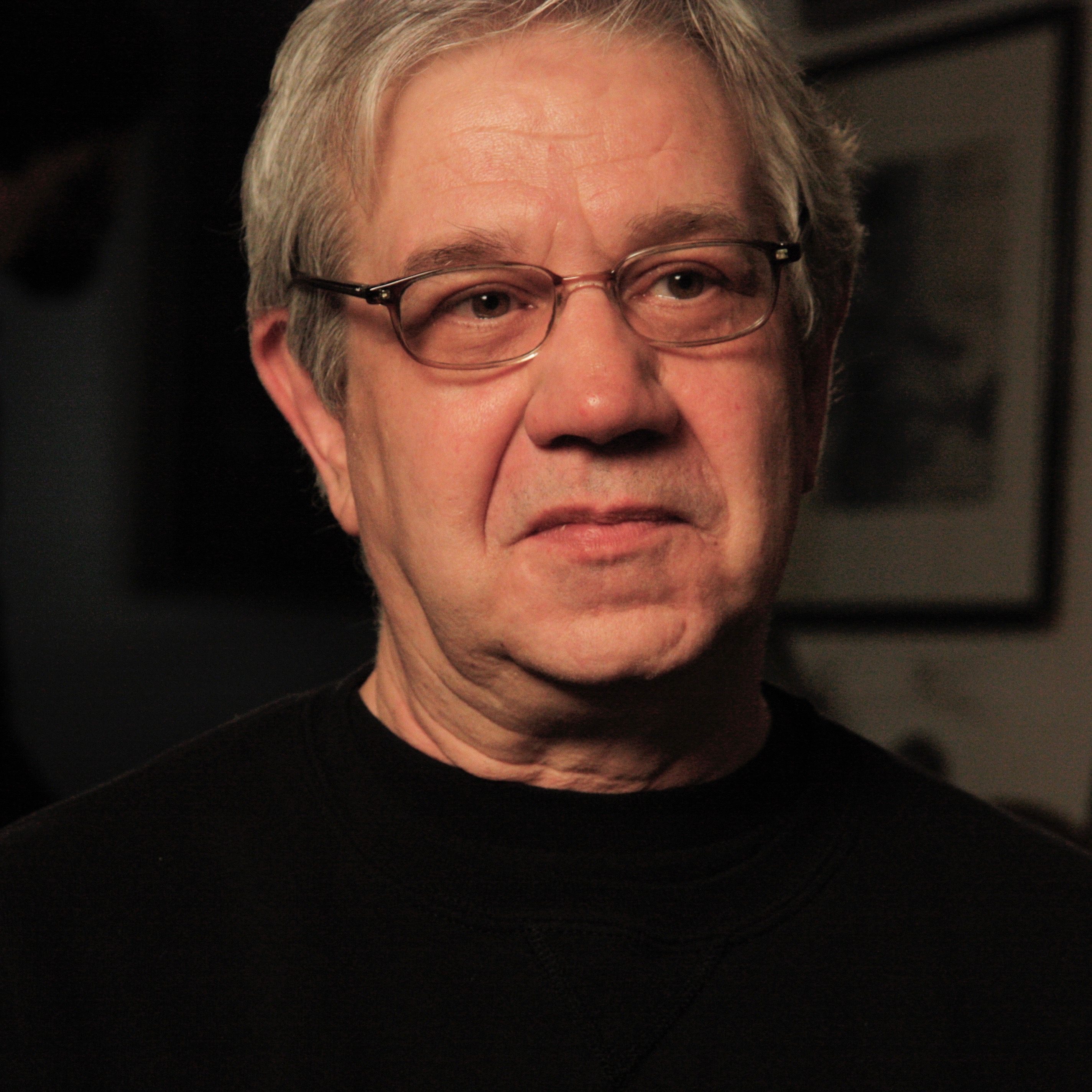

EM Narration: That younger set at Stonewall? It included Martin Boyce, born and raised in Manhattan by working-class parents. During the summer, Martin would spend every night of the week at the Stonewall or on the streets of the Village with a band of mostly homeless teenagers, many of whom dressed in scare drag. These days, they might describe themselves as gender non-conforming. Martin was one of those rare street kids who had a home to go to.

Fifty years later, Martin is a 71-year-old with a poet’s soul. When we meet on Christopher Street outside the Stonewall Inn on a gusty spring day, you’d never guess this kindly looking man with thinning white hair was once a scare-drag-wearing street queen. The two of us look on, as a group of school kids on a field trip play in the small park that was designated the Stonewall National Monument by President Barack Obama in 2016.

———

EM: Today the Village is a really wealthy neighborhood and pretty straight. What was it like through your eyes then? What was the, what was the character of the Village in the 1960s?

Martin Boyce: Well, the character of the Village in 1960s was a welcome mat. I mean, for any dissident group. And, but it didn’t say it was going to be easy. But you felt if you went down there, you were very hopeful that things could go your way. You can make friends and meet other interesting people. But, yes, the Village was a place where biracial couples would congregate, where gays could go, where the hippies, the beatniks at the time, too, could go. And people like that, everybody could find a little spot in the Village or at least tolerance, but real tolerance. They didn’t have to like you, they let you alone, they’d serve you, and they deal with you. And that was all we really wanted from a neighborhood.

EM: What were, what was the terrain like? Was it a five-block range, a 10-bock range? Was it from 6th Avenue to the river, from Christopher north? What was your terrain?

MB: Our place was Christopher Street, Greenwich Avenue, those side streets, and spreading out from the docks within two or three blocks. But it seemed like a world because, psychologically, it changed from Christopher Street near Greenwich Avenue, you know, to the river, this lonesome, lonesome place. Fascinating and dark and interesting.

EM: You had a lot of trouble around the different parts of the city about getting beaten up. Was that ever, was it a fear for you ever in the Village when you were a kid that this was a dangerous place for you?

MB: The Village at the time was a very dangerous place if you went off Christopher on your own, depending what time of night. I mean, there was a lot of gay bashing. But in order to gay bash, they gotta isolate you. It’s almost like a pride of lions, they isolate you and then they get you. For some reason that’s part of the pleasure or that’s part of the way things are. So you had to be wary. The further you got from Christopher Street, the more wary you were.

A typical night out would be to expect nothing, not to make really too many plans because you knew something was going to happen that was out of your control and interesting. It was just interesting to go out, interesting to go to the stoop where all the queens were hanging out, interesting to listen to last night’s stories, especially if you missed one night in the Village. And some queen would get up and tell her story, what happened just the night before, and then there would be a discourse, like approval of what she did or how she handled it, how it could be handled better, and everybody would listen or joke and have fun. You had to give a sense of loyalty, not to that particular group, like a lodge or anything, but to the camaraderie of the street.

EM: How old were you the first time you went to the Stonewall Inn?

MB: Eighteen. I first heard about the Stonewall quickly because I was with a hip crowd so we would really know. It was about dancing, people could dance. I mean, I wasn’t into dancing that much, but the real thing was the excitement of everybody going. When I went to the Stonewall I was of the preferred age, because I was 18 years old, and that’s who they wanted because these are the kind of… It’s like letting women into a bar, you know, you’re going to find men. And if you let young gays in, you’re gonna find, I wouldn’t say predators, but people searching. And sometimes predators.

———

EM Narration: While Martin and his friends were dancing at the Stonewall and cruising the streets of the Village, back in the WBAI studio, the “New Symposium” panelists were pontificating about gay nightlife.

———

Unidentifiable Speaker: Many and various kinds of bars, which might include leather bars or the dance bars, the private clubs, which is a new thing. Since the great purge of the middle ’60s, the clubs started up.

———

EM Narration: As you heard in our last season, the Mattachine Society of New York had turned its attention to fighting entrapment and regulations that made it illegal for gay people to drink in bars—and they’d made some progress.

———

CR: Shortly after the Lindsay administration took over, when harassment and the pressure on gay bars lessened, not particularly because of Lindsay but because of the challenge to State Liquor Authority…

———

EM Narration: By the late 1960s, the routine practice of police entrapment of gay men was allegedly over and gay bars were allegedly legal.

———

CR: Remember, especially since January when Judge Keating ruled that dancing between homosexuals is legal…

———

EM Narration: But that progress was accompanied by an explosion in the number of private clubs, and Craig Rodwell was not a fan.

———

CR: And the reason for the private clubs, it’s the Mafia’s new way of keeping people out they don’t want in there, such as…

Unidentifiable Speaker: Health Department.

CR: Health Department, right. There’s nothing illegal about a gay bar anymore except for the fact that the Mafia is running them and the heat’s on them. But if they call them private clubs, they are a little more insular and have a little more protection.

CP: What are some of the clubs, do you know?

CR: At the moment there’s probably a hundred in Manhattan. New ones every week opening up.

CP: And I know that the Corduroy Club is still going, I’ve checked. The Telstar, I think, is the same setup. The Stonewall’s a club setup, too, isn’t it?

CR: It’s a setup of some kind.

———

EM Narration: As Craig said, the Stonewall was a setup of some kind, which apparently made it ripe for two police raids in the same week of June 1969. But it’s the second raid we remember because that’s when the shit hit the fan.

Next week we’ll bring you voices from that second raid and from the riots it sparked—a series of events beginning in the early morning hours of Saturday, June 28, 1969, that are known by just one word these days: Stonewall.

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: executive producer Sara Burningham, producer Josh Gwynn, assistant producer Mo LaBorde, administrative and special projects manager Inge De Taeye. Sound design and mixing by Rae Kantrowitz. Thanks to our photo editor Michael Green, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Denio Lourenco. Thanks also to our intrepid researchers, Brian Ferree and Brian DeShazor. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season five of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, Irwin and Andra Press, and our listeners—like Hal Brody. Thanks, Hal!

Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. Our website is also where you’ll find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

So long! Until next time!

###