Frank Kameny

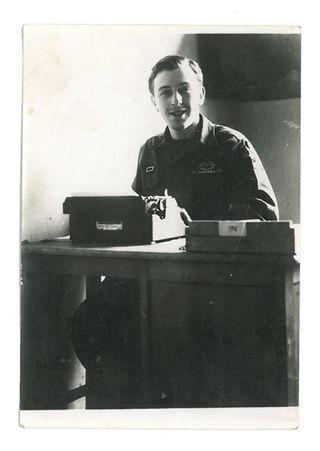

A young Frank Kameny in an undated photo.

A young Frank Kameny in an undated photo.Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: Here are the absolute basics of what you need to know about Frank Kameny, who lived a long and extraordinary life. He was fired from his federal government job in 1957 because he was gay. He didn’t just go home and pull the covers over his head. He fought a successful 18-year battle with the government to change the law so the same thing didn’t happen to other gay people.

Along the way Frank founded a militant gay rights group in 1961 in Washington, DC, and in 1965 organized the first public protests by gay people in front of the White House, among other places. In 1968 Frank also coined the then-radical “Gay Is Good” battle cry. Beginning in the early 1970s, he fought successfully (along with Barbara Gittings and others) to get homosexuality removed from the list of mental illnesses. And Frank’s impressive list goes on.

Listening to Frank’s episode, you learn that he lived by three rules that should inspire us all:

- Have absolute confidence in your beliefs;

- Fight for what’s right;

- Never, ever give up.

———

For a book-length account of Frank Kameny’s legal battle, read Eric Cervini’s Pulitzer Prize-nominated The Deviant’s War: The Homosexual vs. The United States of America.

For students and scholars, there is a treasure trove of Frank Kameny’s papers (77,000 items!) to be found at the the Library of Congress.

View a selection of items from Frank’s Library of Congress collection here.

You can also explore some of what’s available at The Library of Congress on a now out-of-date website devoted to Frank’s papers.

Here’s an article about some of the artifacts of Frank’s activist career that are in the possession of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Executive Order 10450 was used to fire gay people like Frank Kameny from their federal jobs.

In 2009 the U.S. Government officially apologized to Frank for his 1957 firing from his job with the Army Map Service because he was gay. You can read about it here, including the government’s letter of apology.

For a collection of Frank’s letters, which provides insight into his remarkable life and work, have a look at Michael Long’s book, Gay Is Good: The Life and Letters of Gay Rights Pioneer Frank Kameny.

Frank would have been very pleased to know (although he wouldn’t have been surprised!) that he rated a New York Times obituary.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

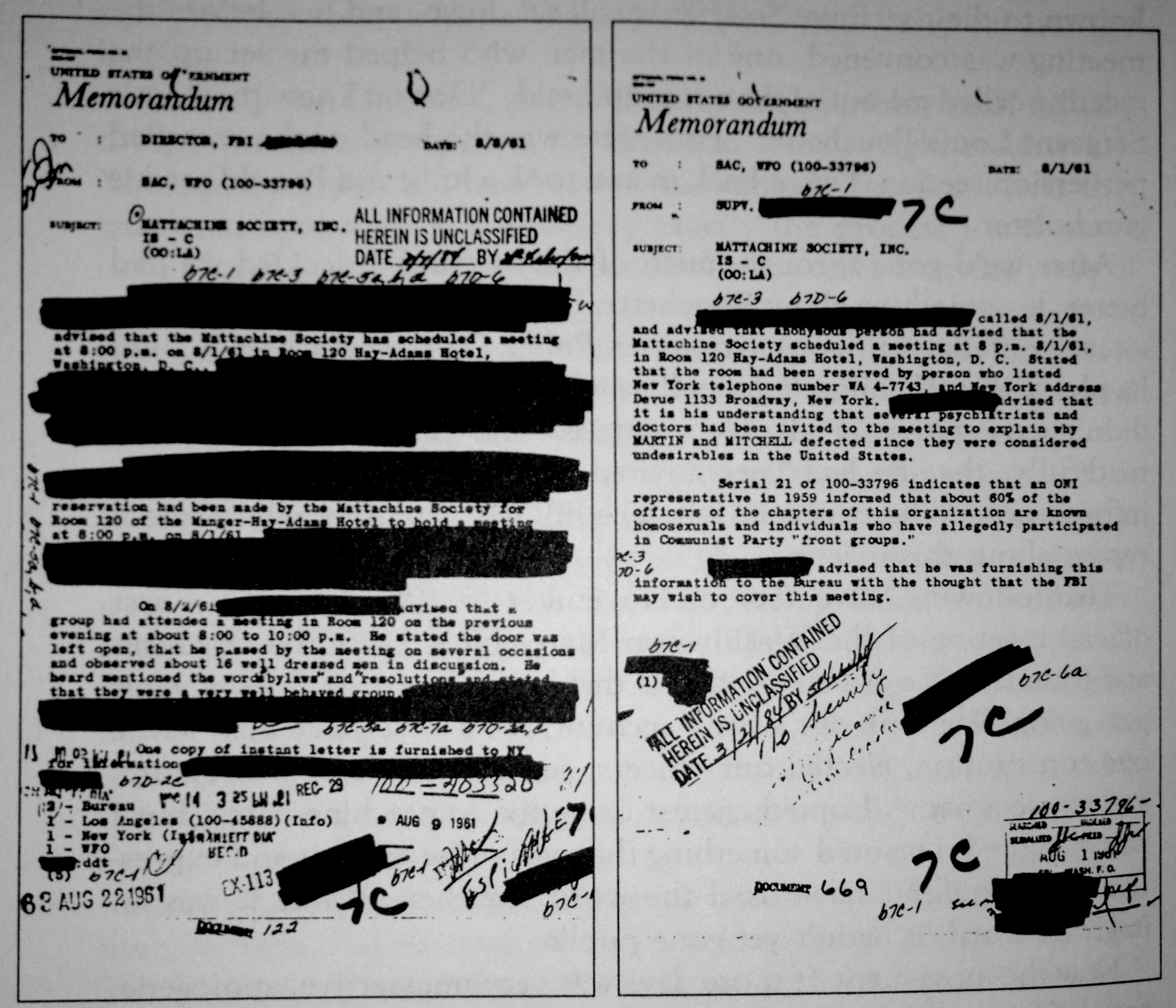

In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed an executive order that essentially banned gay people from federal employment. It was an incredibly paranoid time in our nation’s history. The anti-communists thought they saw subversives behind every tree and traitors under every rock.

So the federal government set out to fire all employees they believed threatened the nation’s security. And gay people were a huge risk. Why? Because they could be blackmailed by foreign spies. And why could they be blackmailed? Because they had to keep secret they were gay. And why did they have to keep secret that they were gay? Because they could be fired from their jobs, lose their homes, even lose their families if anyone knew they were gay. Don’t bother trying to figure out that logic because it’ll make your head explode.

One of the people who lost his job because he was a known homosexual was an astronomer employed by the Army Map Service named Frank Kameny. They had no idea what they were doing when they fired Frank.

Frank wound up becoming one of the most militant and important thinkers and leaders of the LGBT civil rights movement long before it was called the LGBT civil rights movement or even the gay rights movement.

So I went to Washington to interview Frank. It was a surprisingly mild early June day when I arrive at Frank’s house in Washington, DC. It’s a modest two-story post-war brick Colonial in a leafy prosperous neighborhood just outside the center of the city. His house is a bit scruffy around the edges with a lawn that could use some attention, too.

Frank greets me at the door wearing a white button-down shirt and gray slacks. He looks like a retired scientist out of central casting. And he’s a bit scruffy around the edges, too. So Frank strikes me as the kind of person you’d expect to have a pocket protector in his shirt pocket filled with a half dozen pens and pencils.

I don’t get a tour of the house. We go directly to Frank’s office. There are files and unidentifiable dust-covered piles everywhere. Frank takes a seat behind his desk. He motions for me to sit, and is ready to go. I quickly clip the microphone to his shirt because I don’t want to miss a word. He’s already talking as if addressing an auditorium filled with hundreds instead of an audience of one.

A lesson I learned a long time ago is that when a bulldozer is coming toward you, get out of the way. Frank was a bulldozer and I’m going to get out of the way and let him tell his story.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Frank Kameny. June 3, 1989, at the home of Frank Kameny in Washington, D.C. Interviewer is Eric Marcus.

Frank Kameny: You will learn when you talk to me that I cast my sentences by putting all the modifying clauses and words at the beginning. And you have to listen, and go along, and ultimately you will find what it is that I am modifying. So…

EM: And my tendency is to interrupt, so do whatever you need to.

FK: Alright. So, I was called in and [they] said that “We have information that leads us to believe that you are a homosexual. Do you have any comment?” I said, “What’s the information?” They said, “We can’t tell you.” And I said, “Well, then I can’t give you an answer. You don’t deserve it. And in any case, this is none of your business.” Which got them upset because bureaucrats never like to be told that something is none of their business. That basically was the interview. Ultimately, it resulted in my termination late that year.

EM: You must have been shocked.

FK: Yes, of course. And, um, …

EM: How did they do it? Did they come into your office?

FK: No. They issue a… The way the government does anything, they issue you a letter.

EM: Did they say, “We’re dismissing you because you were a homosexual”?

FK: Yes, for homosexuality. Such firings were not uncommon in that period.

EM: Were you depressed by it?

FK: Naturally, because I had no source of income. And the next two or three years were extremely difficult. In fact, by the time I got into 1959 I was living for about eight months on 20 cents’ worth of food a day, which even by 1959 prices was not terribly much. It was a great day when I could afford five cents more and put a pat of butter on my mashed potato.

But meanwhile, by that time, I had decided that basically what this amounted to was a declaration of war against me by my government. “A,” I don’t grant my government the right to declare war against me. And “B,” I tend not to lose my wars.

I went through such appeal procedures as there were, which take you through the lower level of the bureaucracy and then, on the philosophy that ultimately the head of the executive branch of the government is the president, you go to the top. And I have always gone to the top on these things. So I worked my way right on up without success, ultimately to letters to the president.

I—my feeling is that you always pursue things to their final conclusion. I was put in touch with a local attorney who had been a congressman and who was willing then, having exhausted everything, my having exhausted everything, to take my case on a contingent fee basis, since I had no money.

In 1960 the U.S. Court of Appeals turned it down. And he indicated that he felt it was hopeless and therefore he didn’t want to pursue it further. I said I did. So he gave me a copy of the Supreme Court rules and told me about filing pro se documents. Pro se means for yourself. And in theory, any citizen can any time do anything that a lawyer will do, can do it for himself if he chooses. It’s not always wise, but you have the prerogative under our system always of doing it for yourself. You’re not required to have a lawyer.

I had the rule book. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Supreme Court procedure. It’s a double round. You have two knocks at the door. Your first effort is a knock at the door to say, “Will you let me in or won’t you let me in?” And if they say no, that ends it. If they say yes, then you prepare all your briefs and really go at it. The first knock is called a petition for writ of certiorari.

And so he gave me some other petitions. And whenever I had questions… My philosophy then, as now, is, I pay for the government with my taxes, therefore they’re there to serve me. So if I had questions I called up the Supreme Court. Or walked over there and said, “Here’s my question. Give me an answer,” which they did, very nicely. Not the justices obviously. And I ultimately drafted and filed my own petition.

The government then put its disqualification of gays under the rubric of “immoral conduct.” The word simply does not belong in any issuance in this country. Morality is a matter of personal opinion and individual belief on which any American citizen may hold any view he wishes and upon which the government has no power or authority to have any view at all. But more than that, then having stated a general principle, you have to apply it very specifically and pointedly to the case at hand and that was that, in my view, homosexuality is not only not immoral, but is affirmatively moral. And that was the theme that underlay that. And that was the direct address to the government’s policy. And it had to be said and nobody else had ever said it that I know of in any kind of a formal court pleading.

And in March, not unpredictably, came the letter. As I recall, it was on blue paper. I still have it upstairs, signed by Chief Justice Warren, indicating that I had been, that certiorari had been denied. That ended the formal case. But the battle went on for another 14 years.

EM: What the government essentially did is they turned an intellectual, bookish astronomer into a radical.

FK: Thank you for using that word. I have had cases over the years that I’ve handled of meek, mild, unassertive, un-aggressive people who just want to go about doing their work and suddenly they are hit hard. They are trampled upon with a hob-nailed boot and suddenly it does exactly that: it radicalizes them. And off they go marching militantly. And case after case after case. So, anyway…

EM: So by ’61 you had become radicalized.

FK: Oh, very much so. Very much so. So anyway…

EM: Oh, boy, they had no idea what they were getting themselves into.

FK: So, anyway, we founded the organization. And now the movement of those days… And I say this next, not critically, and not necessarily derogatorily, because it was a very, very, very different era. We were sick. We were sinners. We were perverts. You have your long litany of pejoratives. There was absolutely nothing whatsoever which anybody heard at any time anywhere at all which was other than negative! Nothing! And so the movement, predictably, in retrospect, responded accordingly. And that was the nature of the movement.

EM: People were frightened and they had good reason to be.

FK: It was not only frightened, it was simply a lack of intellectual strength. We had to defer to the experts.

EM: Oh, you hated that, didn’t you?

FK: My answer was, “We are the experts on ourselves and we will tell the experts they have nothing to tell us!” But it took a few years to get that across.

The movement of those days was a very unassertive, apologetic, defensive kind of structure. Not taking strong positions. Giving a hearing to everybody and saying, “All views must be heard, even those which are the most harshly and viciously condemnatory. As long as it dealt with homosexuality they must be given a fair hearing.” Drivel! And I… That didn’t suit my personality. And the Mattachine Society of Washington was formed around my personality.

We characterized ourselves within the movement as an activist militant organization. Well, those were very dirty words in those days in the movement, such as it was. This was ’61 and ’62.

EM: No one else was, except for the civil rights movement, just…

FK: It was just beginning. Even within the gay movement, even more so. You weren’t supposed to be.

EM: Did you have an overall goal? A stated plan of what you were going to do as an organization?

FK: That was sort of set out in our statement of purposes, which I could dig out.

EM: Generally, what was it?

FK: Generally, to work for gay rights—although gay rights as such wasn’t necessarily the phrase of choice of those days. But to achieve equality for homosexuals and homosexuality against heterosexuals and heterosexuality. Equality, I guess, was the primary theme.

EM: That wasn’t born in ’69, those ideas.

FK: Oh, certainly not! ’69 wouldn’t have happened if we hadn’t come along.

EM: But as you well know, that’s not how it…

FK: Well, they’re wrong. We started—to digress before I get back—we started picketing here in ’65, which first created the mindset which allowed for gays doing openly public things by way of demonstration, as gays. There would not have been Stonewall if the mindset hadn’t already been established by us for that in ’65, with our subsequent demonstrations year by year, which were widely publicized in New York, at Independence Hall every Fourth of July each year after ’65. And which was being publicized in ’69 in preparation for that one when Stonewall occurred. And it would have never have occurred to gay people to do anything publicly if we hadn’t already started it.

EM: What happened to your case, though?

FK: My case was dead with the Supreme Court. That ended that permanently.

EM: The commission changed its rule in ’75. You must recall first hearing about that.

FK: They called me up. By that time I was on—I speak with obvious hyperbole and figuratively—on virtually daily communication with the general counsel of the Civil Service Commission. He knew my cases. He knew other things that had come along.

EM: So people were coming to you.

FK: Oh, yes, he had informed me 18 months before, in ’73, that they were beginning the process of changing their policy, but there were a lot minds that had to be changed inside the commission, and he informed me that it was going to come out on July 4, except that July 4 was a holiday, so it was going to have to be July 3, very appropriately. And that’s when they issued the news release and the formal change in policy.

EM: July 3, 1975.

FK: Yes, 1975. Of course, in ’78, under the Carter administration, the Civil Service Reform Act went through Congress and that abolished the Civil Service Commission under that name. It’s the Office of Personnel Management—the O.P.M. changed all the laws. So that, that’s one battle, one book, that has nicely been closed and put on a shelf as a complete success.

So at this point I’m sort of, I don’t know, people call me a living legend or…

EM: I’ve heard that phrase. Do you like being called a living legend?

FK: It doesn’t bother me. It’s complimentary. Or humorously, the world’s oldest living homosexual. Or the grandfather or the great-grandfather of the gay movement, which is not technically correct, as you well know.

Life takes its turnings, and you don’t foresee them. But ultimately, I think, in retrospect, life has been more exciting and stimulating and interesting and satisfying and rewarding and fulfilling than I ever could possibly have dreamed it would have been.

———

EM Narration: I hope that by hearing Frank’s voice and a bit of his story that you have a sense of why he continues to inspire me and so many others.

There are three key lessons that Frank has taught me that I want to share with you: have confidence in your beliefs; fight for what’s right; and even in the darkest of times, never, ever, give up.

We’re recording this two days after the election and part of me feels like giving up. I’m scared. I’m angry. I’m heartsick. But part of me also feels like I need to do something. On my own. And collectively. So I’m going to hang on to Frank’s fighting spirit for inspiration and remind myself that he didn’t give up. I shouldn’t give up. We shouldn’t give up. Not now. Not ever. No way.

I have two favorite photographs of Frank that I’ve posted on our website at makinggayhistory.com. The first is from a protest Frank organized and led in front of the White House in 1965. So for anyone who thinks there wasn’t a gay rights movement before 1969, look at that photograph. They are dressed in coats and ties for a good reason. Frank was an incredible marketer. His belief was, “Don’t get in the way of your message.” And if you wear a coat and tie and the women wear skirts and heels—which looks pretty ridiculous to our eyes—they knew, Frank knew, that you don’t get in the way of your message.

Frank is carrying a sign that says, “We Want: Federal Honorable Discharge…”—they weren’t even fighting to stay in the military; they at least wanted honorable discharges if they were thrown out—”Security Clearance…”—because you couldn’t get a job in the government and needed security clearance—and they wanted “Conferences with Our Government Officials.” So you’ll see that sign that Frank is carrying.

The second photo is of Frank shaking President Obama’s hand at a 2009 White House ceremony after signing a memorandum providing benefits to the same-sex partners of federal employees. This was before marriage equality became the law of the land. You can only see Frank from the side, but his smile and the President’s smile light up the room. In 2009, Frank also got a formal letter of apology from the U.S. Government for having fired him in 1957. Persistence paid off.

For a man who fought to break down the barriers between the federal government and the nation’s gay citizens, it seems fitting that Frank’s extensive papers now reside in the Library of Congress. And that’s thanks to the efforts of my friend Bob Witeck and several others.

Frank died on October 11, 2011, just weeks before his house was listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. You can find it online. Frank was 86.

———

Many talented people made this podcast possible. Thank you to our executive producer, Sara Burningham; our audio engineer, Casey Holford; and our composer, Fritz Myers.

Thank you also to our social media guru, Hannah Moch, for getting the word out about us; our webmaster, Jonathan Dozier-Ezell, who’s made our podcast website a beautiful thing; and Zachary Seltzer, the man responsible for each episode’s show notes. We had production help from Jenna Weiss-Berman, who believed in this podcast even before it was a podcast and always gives me good advice.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Funding is provided by the Arcus Foundation, which is dedicated to the idea that people can live in harmony—we can hope—with one another and the natural world. Learn more about Arcus and its partners at arcusfoundation.org.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also listen to all our episodes on makinggayhistory.com. That’s also where you’ll find photos and information about each of our interview subjects, including Frank Kameny.

So long. Until next time.

###