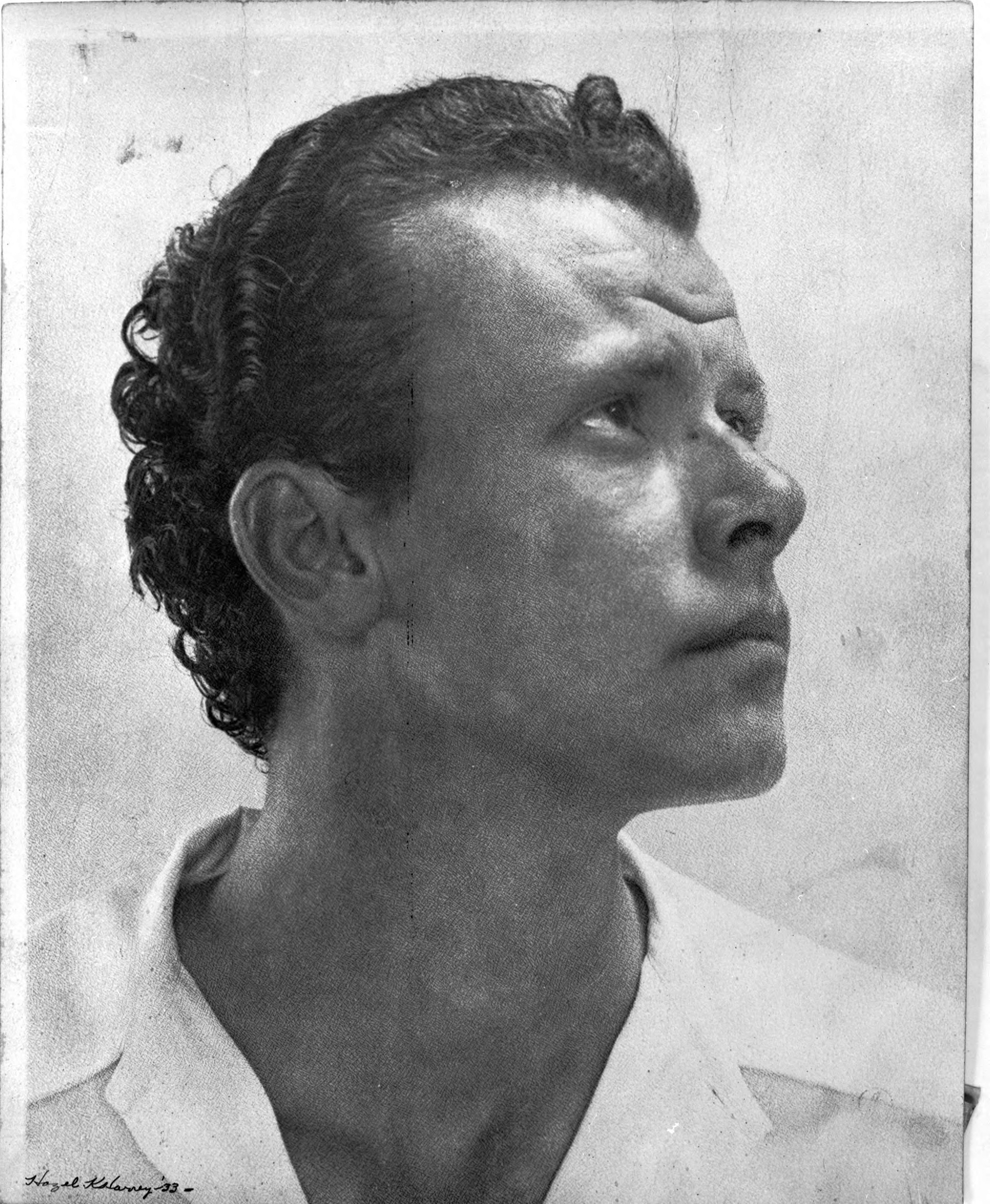

Harry Hay

Harry Hay, Los Angeles, CA, 1989. Credit: Photo by Robert Giard © Jonathan Silin, courtesy of The New York Public Library.

Harry Hay, Los Angeles, CA, 1989. Credit: Photo by Robert Giard © Jonathan Silin, courtesy of The New York Public Library.Episode Notes

Harry Hay was precocious. He knew from an early age that he was attracted to men, had his first gay sexual experience when he was nine, and developed an interest in union organizing in his early teens while working on an uncle’s farm in Nevada. Born to an upper middle-class family and raised in California, Hay was sent to the farm by his father to toughen up, but what he learned working side by side with migrant laborers was first and foremost ideological, as many of his fellow workers were “Wobblies,” members of the International Workers of the World (IWW).

By the early 1930s, Hay was out, had dropped out of Stanford University, and had moved to Los Angeles to work in the theater. His lover, actor Will Geer (who gained fame in the 1970s in the role of Grandpa Walton on the popular television series, The Waltons”), recruited him into the Communist Party. Together they performed agitprop street theater meant to incite people to protest against Jim Crow, anti-Semitism, and other societal ills, and they demonstrated for the right to unionize.

Anti-communist sentiment at the time taught Hay much about guarding the anonymity of his fellow Reds—lessons he would carry to his other activist cause: gay rights and the establishment of the Mattachine Foundation in 1950. While the Mattachine Foundation (later the Mattachine Society) was not the first gay rights organization in the U.S., it was the first to last and spread across the country, albeit under different leadership.

As Harry Hay’s 2002 obituary in the New York Times stated, “Hay’s contribution was to do what no one else had done before: plant the idea among American homosexuals that they formed an oppressed cultural minority of their own, like Blacks, and to create a lasting organization in which homosexuals could come together to socialize and to pursue what was, at the beginning, the very radical concept of homosexual rights.”

In 1953, Hay—and the other leaders of the Mattachine Society, including Chuck Rowland (featured in this MGH episode)—was ousted in part because his communist affiliation, which was deemed a liability by an insurgent group of more conservative members of the organization, including Hal Call (featured in this MGH episode).

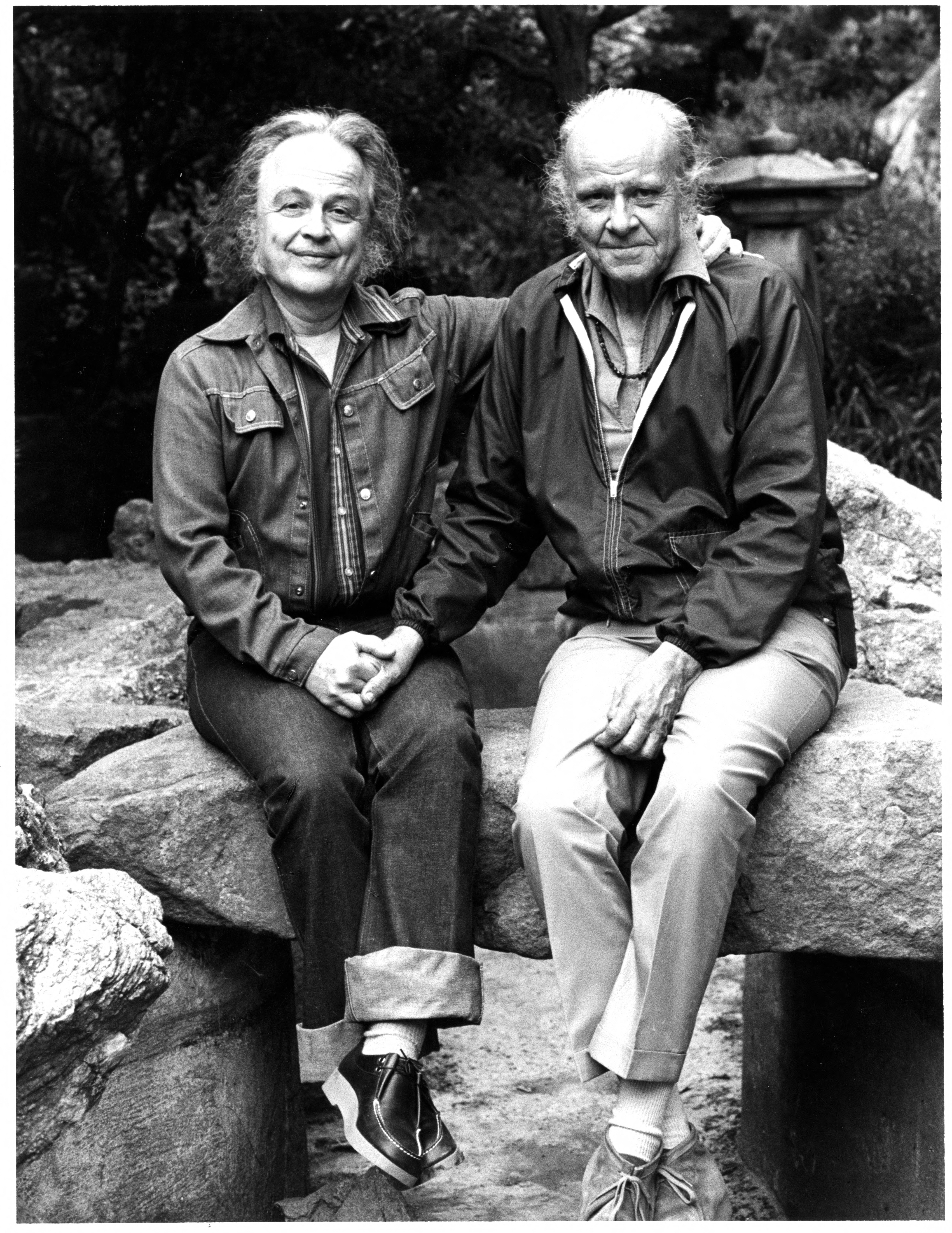

Hay’s gay rights activism didn’t end with his Mattachine ouster, however: in 1966 he co-founded the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations (NACHO) and in 1979 the Radical Faeries, a “mixture of a political alternative, a counter-culture, and a spirituality movement,” in the words of Hay’s biographer Stuart Timmons. The anti-assimilationist group, which drew inspiration from Marxism, paganism, anarchism, and Native American spirituality, was also co-founded by John Burnside, who was Hay’s partner from 1963 until Hay’s death in 2002. Radical Faerie sanctuaries and gatherings exist to this day.

———

Read more about Harry Hay in his San Francisco Chronicle obituary. For a more in-depth look at the early days of the Mattachine Society, check out C. Todd White’s Pre-Gay L.A.: A Social History of the Movement for Homosexual Rights and James T. Sears’s Behind the Mask of the Mattachine: The Hal Call Chronicles and the Early Movement for Homosexual Emancipation, and listen to our episodes featuring Chuck Rowland, Herb Selwyn, and Hal Call, who wrested control of the Mattachine from Hay, Rowland, and the other original members of the group.

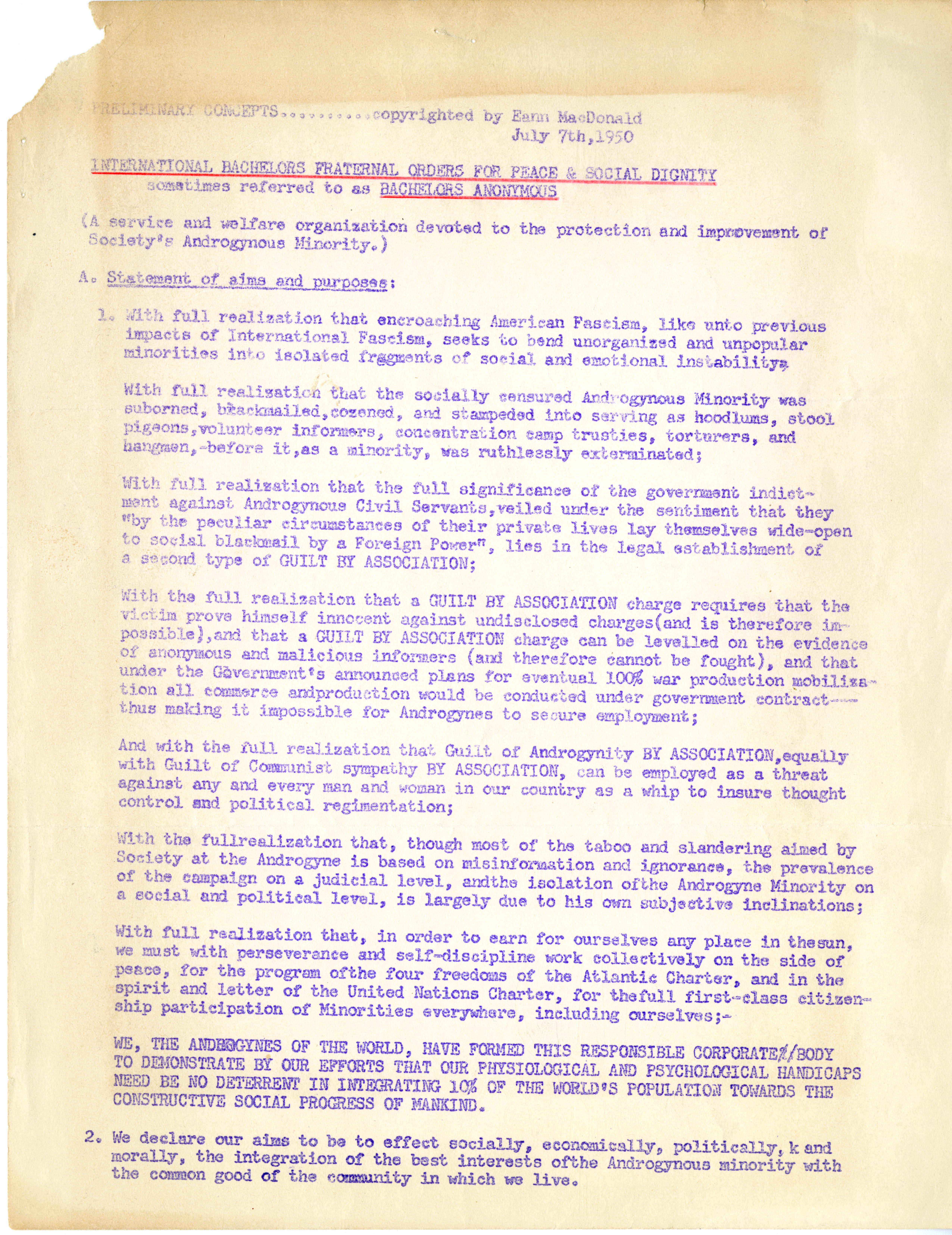

In the episode, Hay mentions the “call to the society” that the early Mattachine Society used to gauge the interest of potential new members in joining; you can see the prospectus (written by Hay under the pseudonym “Eann MacDonald”) in its entirety if you scroll down past the transcript of this episode. And you can listen to an episode from Devlyn Camp’s Mattachine Podcast about “The Call” here.

In 1983 Vito Russo (whom you can hear in this MGH episode) interviewed Hay and Barbara Gittings (who was featured, along with her partner Kay Lahusen, in two MGH episodes, which you can listen to here and here) for his Our Time TV program. Here are part one and part two.

Hay is featured in the 1984 documentary Before Stonewall, which also includes interviews with MGH luminaries Edythe Eyde, Barbara Gittings, Frank Kameny, Chuck Rowland, and Dr. Evelyn Hooker.

As he says in the episode, Hay had a fondness for the word “fairy,” and in 1979 he would go on to co-found the Radical Faeries. Philippe Roques made a documentary short about the movement titled Faerie Tales. The Radical Faeries website has a tribute page to founders Harry Hay and John Burnside.

In the episode, Hay touches on a short-lived gay “social group” begun in 1924 Chicago. This is the Society for Human Rights (SHR)—the oldest documented gay rights organization in the United States. SHR was founded by Bavarian-born Henry Gerber (1892–1972), who drew his inspiration from Magnus Hirschfeld’s work with the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. Listen to our MGH Magnus Hirschfeld here. More on Gerber and SHR here.

The author whose work had such a profound effect on young Harry Hay (and who introduced him to the word “homosexual”) was Edward Carpenter (1844–1929), known as the “sexy sage of Sheffield.” Carpenter was a gay socialist philosopher and pioneering advocate of sexual freedoms. You can read all about him in the biography Edward Carpenter: A Life of Liberty and Love by Sheila Rowbotham.

Another author mentioned in the episode is Dr. Alfred Kinsey, whose work provided talking points for some of the early Mattachine discussion groups. Dr. Kinsey authored two landmark books about sexuality: Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948), and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953). The Kinsey Institute at Indiana University offers extensive information and research on human sexuality and gender.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History!

The first sustained gay rights group in the U.S.—the Mattachine Society—sprang directly from the mind of Harry Hay in 1950. Harry was the gay rights pioneer who paved the way for everything that came after. So if this fourth season of Making Gay History is an exploration of beginnings, Harry Hay was there at the inception of the movement in the U.S.

But if you skim the pages of the Making Gay History book, from which this podcast is drawn, you won’t find Harry’s interview. And that’s not because when I tried to shake his hand goodbye he grabbed my face and planted a wet kiss on my lips. Although that definitely pissed me off. Nor is it because of his tut-tutting, which drove me nuts. And it’s also not because he lectured me, almost as if I weren’t there, resisting my questions, and paused only to call me “sweetie” or “dear.” It’s because I needed Harry to fill in some key building blocks on how the gay rights movement in the U.S. was born.

But there was no corralling him and after a very frustrating 90 minutes, he had to leave for a doctor’s appointment and I was heading back to San Francisco. We were out of time. And I can see now from reading my post-interview notes, I was also out of patience.

Harry was a theorist. An activist philosopher. He was more interested in expounding on the arc of homosexual history starting with the ancient Greeks, than telling me the story of how he founded Mattachine, which is why I wanted to interview him in the first place.

But 30 years later, listening to Harry’s tape was a revelation. Now, I could hear Harry’s story loud and clear. And it’s about carving out an identity in a society that says you don’t exist.

One more thing you should know about Harry Hay is that he was something of a time traveler. He was born at the end of the Edwardian era in England in 1912, but raised in California—where his mother dressed him as little Lord Fauntleroy. That’s a fictional character straight out of a 19th century children’s novel. Think black velvet jacket and matching knee pants worn with a fancy blouse with a large ruffled collar and a floppy bow.

But in 1989, Harry greets me at the door of his broken-down Hollywood, California, bungalow dressed like an aging hippie. Beaded necklace, ample sideburns, long gray hair, a single dangling earring. He looks every inch the Radical Faerie. He was a co-founder of that movement, too.

We step into Harry’s cool, book-lined living room and take our seats. I clip the microphone to his shirt and press “Record.”

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Henry Hay, Friday, August 24, 1989. Location is Los Angeles, California. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Harry Hay: Every class has to good, has to have a good available sissy. One sissy, anyway, is the scapegoat. And so all of a sudden I quickly became chief sissy, you see.

EM: What kinds of things did they say besides…?

HH: Because after all, honey, I was, I really was a sissy. Don’t kid yourself. I mean, you know, I threw a ball like a girl. I walked differently than the boys did, and I knew that I felt differently than the boys did. I knew I saw differently than the boys did, and, um, I had a tendency to cry. And I liked poetry and all those things that boys are not supposed to like, you know. And they would call me a fairy and I knew that fairy was a terrible word, but I kinda liked it. Secretly, I liked it.

Uh, when I was 11—this is 1923—I managed to get a book out of the locked glass case behind the librarian’s desk. This is a book by Edward Carpenter. I’ve got lots of Edward Carpenter up there now, um… Um, from the look on your face, you don’t seem to know him, do you? Well…

EM: A lot of things I don’t know.

HH: Let me… Edward Carpenter is one of the great, one of our great forebears in this regard. What we do know about the personal life of Walt Whitman, we know from Edward Carpenter, who came here and stayed with him twice. So, as I said, I’m reading this book and, um, he was, the book itself was published in 1921 and, and he’s talking all about the Greek tradition and how they were, each one was everything to the other person completely, that there were a totality between the two of them, and lifelong lovers. And he talks about the Romans and doing the same thing. Then it goes down to, you know, Michelangelo and William Shakespeare, and so on, and it uses the word “homosexual.” And I’ve never heard of that. And I don’t know what it is, and I go look in the dictionary. Of course, it isn’t there. Um, it won’t be in any American dictionary until 1937.

EM: Until ’37?

HH: That’s right.

EM: So even if you knew the word “homosexual,” you couldn’t go to the dictionary and look it up.

HH: Well, as I said, if I’d had the sense I was born with, I would have gone downtown to look in the penal code, I would have found it. It’s in the penal code and in the medical code, but it wasn’t in the libraries. So anyway, I can’t find out what it means, but I know. I just know it’s me. And it’s wonderful, because up until this point I have thought I’m the only one of my kind in the world. I have absolutely no one I can ever talk to, I’m something peculiar and strange and different, and it’s beautiful, but nevertheless there’s no one to talk to.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: Harry spends the next decade looking for someone to talk to. And, ironically, it was his self-made, autocratic father who helped Harry find his way to other gay men. He sent Harry out into the world at 13 to work on his uncle’s farm doing heavy manual labor. Harry hits the road as a seasonal farm worker, then heads for San Francisco. He pays his way down the California coast by working on merchant ships. That’s where, at age 14, he meets his first lover. Eventually, and a few lovers later, he finds his way to a new life in Los Angeles.

———

HH: By 1930, of course, I am out, shall we say, because in February of 1930 I’ve made contact with the man who introduces me more or less to gay life here in Los Angeles. And, um, it turned out that he had been the, um, protege of a doctor in Kansas City, where he had recently come from, who had been interned at one time in St. Louis and before that in Chicago. And in Chicago, he in turn had been the friend, the young friend of an older man, who at one time had started a group of homosexuals in Chicago in 1924.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: Did you get that? Maybe not, because the thread of history is rarely straight. So let me untangle this for you. The thread begins with Magnus Hirschfeld, who founded the first gay rights organization in 1897 in Berlin, and in 1919 he founded a sexuality institute. Inspired by Hirschfeld’s institute, German immigrant Henry Gerber founded a short-lived gay group in Chicago in 1924. That’s the organization Harry just mentioned. So how do we get from Henry Gerber to Harry Hay? It’s almost like a game of telephone where a single message is passed from person to person. In this case, the message was to bring people together to fight for our rights—and through a series of filament-thin connections across time, and between friends and lovers, that message was whispered in young Harry’s ear.

———

HH: And this doctor in turn had another protege, who was the guy who picked me up. And he told me how dangerous it was, how I must never have anything to do with anything like that at all because it was so dangerous…

———

Eric Marcus Narration: And that was the other message that was coming through to young Harry Hay, but this message was far louder and more clear…

———

HH: Just simply stay away from it. In every state of the union, that it would ruin you for life. So I was warned.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: It was a terrible idea to even try to build an organization for homosexuals.

———

HH: We ourselves have always been, up until the 20th century, we have been seen as outlaws. We are beyond… The law doesn’t cover us. In the church, we oftentimes talk about the picado nefando, and they always speak of our sin as the nefarious sin. And that’s a nice word, until you look at the word, because what it really means: the sin for which there is no forgiveness. Every other sin, you can go through 40 years of penance, but it can eventually be forgiven, but that one is not forgivable. Now why? Very interesting, why. And the Emperor Domitian who had you burned at the stake for it.

Others had you, uh, obliterated by stones, but the point was that you were wiped out, so there’s nothing left for the, when the body is called for to go into resurrection in the last day. There would be nothing left of you. That’s what obliteration means. So therefore there’s nothing left. There’s no place for the soul. All right? The reason why is because you have taken the law in your own hands, and the point is, if you will take this law and even though we burn you and even though we stone you and even though we do all these things, you take the law anyway—what other law would you take into your own hands? You are a danger to the state because you have deliberately take a law and break it. We can’t afford to have you exist. That’s why we have always been an outlaw and why we continue to be that outlaw.

One of the things that I have been saying all along is that—and this is something that has to be said in the histories, I believe—is that the middle class never established anything brand new. This is something they don’t do, they don’t do this well at all. The drive to do something revolutionary and different is going to come from people who have already been working as outlaws and knew how to do this.

EM: How then in 19—, this is late ’40s, early ’50s, did you come to have conversations with people about doing something that was…?

HH: Because in 1930, dear, I was, as a communist and a trade union member, fighting for the oppressed. And therefore I saw my, our own people as oppressed as these people were, so that I had been practicing taking the law into my own hands for a long time. And so in 1934, when I was, uh, working in the theater, I fell madly in love with the leading man whose name was Will Geer. Uh, he was a man who eventually showed up in The Waltons and the various things you may know him by that…

EM: I know exactly who he is. So this was in ’34, you fell… and he fell in love with you.

HH: We became lovers, and in the course of that, he was a member of the Communist Party and he recruited me. In that period we, we would never have kept an address book. We would have never kept records. We have never kept a telephone book at our houses because people could be, uh, could be identified through us. Well, any of us left of center had gone through that training, so that in 1950, when we were starting the Mattachine, we are going to be guaranteeing anybody who comes anywhere near our groups that any of us who have the names and addresses of people will take the Fifth Amendment before we ever, before we ever give away anything. And that integrity, as a matter fact, was tremendously important because this had not happened to gay people.

Up until that time they had been usually betrayed by somebody somewhere along the line, or they would find somebody’s telephone book or somebody’s address book and all kind of people would be exposed. We didn’t have any lists. We didn’t allow ourselves to have pictures taken in a group. So that’s one of the reasons why there are no pictures of that period.

EM: The only picture from that period is…

HH: The picture that John Gruber took.

EM: At Christmastime… which he’s getting me a copy of.

HH: Christmas 1951 at Chuck Rowland’s house.

EM: Right. There were no pictures.

HH: No pictures. We knew at this time that we had to set up a facade. We had to have a respectable, socially acceptable legal facade behind which we could operate as we needed to operate. And what we had thought to do was to set up a foundation which would sponsor semi-public discussion groups, based on the Kinsey Report, which is out at this point. Now we’re using that, I’m using the chapters and the various points that are in that, to have people to openly discuss this.

And the public discussion groups were set up in such a way that everybody who came did exactly the same thing: “I have a friend who…,” or “My father, my uncle who lives in Alaska…,” or “I had a cousin who killed himself last year, but he lived in Montreal,” you know, and then on and on and on, and they, so all the autobiographies come out in the form of “I have a friend who…” or “I’ve got an uncle, his…,” you know, which is okay. That’s great because… Oh, we got the points out. We discuss all the things we need to discuss and people occasionally forget and say “I” instead of “him.” But, you know, outside of that, you can forgive those little, little slips.

EM: So they created their own facade.

HH: And, uh, so the, within the discussion group, there are members of the society, which is a separate group is behind this, and it’s a closed group who are conducting this discussion. And who are watching to see whose eyes get inordinately bright and have a gleam going, which is more than ordinarily interested. In other words, the veil has raised and you’re looking at the person. And you take that person aside and invite him to have supper with you, and if he seems to be sufficiently interested in what we’re all interested in, you show him “the call” to the, to the society.

EM: What is that?

HH: We had a call to come together to begin to develop a gay organization.

EM: You say, “show him the call.” Was it printed?

HH: Oh, sure. It was a five-page thing, as a matter of fact, the original call. And, um, then if he was interested in that, then you invited him to a guild meeting. The society was set up in guilds, and you invited him to, uh, a guild meeting and, um, then… But his acceptance into the group would have to be unanimous. All the things that we did in the society and the foundation were unanimous. We did not vote.

EM: It’s not an easy thing to achieve.

HH: No, it wasn’t, but the point was that, and this was my thinking, too, that we, as far as we knew, we were the first kind, this kind of an organization in the United States, in the history of the United States. We didn’t know of anything else, and this is the height of the McCarthy period. And all of us who are organizers were all way left of center, as a matter fact, we were Reds. And so consequently, we felt that, that we mustn’t make a mistake, or if we did make a mistake, that we would set back the whole idea of a gay organization for years to come, that we’d just terrify everybody.

And, uh, uh, it happens that the found… the Mattachine Foundation was made up of, um, my mother as president, um, Conrad Stevens his mother as secretary, and his sister, I think, as treasurer. Um…

EM: So you asked your mother to become involved because you needed a presentable front.

HH: We, we, we knew we needed heteros to, uh, to found the foundation. The foundation would have to be that.

EM: You needed what, I’m sorry?

HH: We needed heteros for the foundation, we recognized that. And we recognized the fact that we would have to have hetero people who would, with whom we could work and who could hear us. And so I, asking my mother, um, I knew that she was, let’s say, the most respectable person that I could possibly think of who had a certain, she had a certain standing here in the community, and this was what she was doing in 1952.

EM: Did she have any idea what she was president of?

HH: Large… To some extent, she did. And, consequently, all the other young men who were part of the board of directors of Mattachine Foundation she loved. She thought they were wonderful people and she felt they were doing a very interesting job and she did agree, agree that this was an idea whose time has come.

EM: And the idea, the idea that…?

HH: That gay people should be finding their own place, and that the laws should be being changed to recognize who they are. Because by this time, you see, the Kinsey Report has come out, and I’ve given her the Kinsey Report to read. But these are the people who are, who are acting, going to be there for the foundation, who will be therefore present, presenting us to the society at large, and this is what it really amounts to.

EM: Yeah, why couldn’t you do it yourselves?

HH: Well, in the first place, we’re totally illegal.

EM: Why were you totally illegal?

HH: We were totally illegal because, um, perverted acts are… Homosexuality in itself is totally illegal. And, uh, uh, to be a homosexual meant, among other things, that you were, as I said, a degenerate performing degenerate acts, and so consequently you would be fired from your job. You would lose your insurance. You would be thrown out of your apartment. Um, if at any moment… The great threat, which the red, the vice squad held over everybody’s head was that if you were ever caught in any, uh, in any situation where you were in violation of 647…

EM: Which was?

HH: Which is the lewd and lascivious act in the state penal code. Um, there’s 647, a, d, a through f, I think. There’s all these various… But if you make the mistake of raising one eyebrow, uh, rather than both you’re, it’s like that, you would be in trouble as far as the cops are concerned. They immediately assume that you are making an assignation, and this therefore leads to licentious conduct and that is illegal.

This, this had been the law for as far as we knew all the way back. This is what we were told, and so consequently the idea, uh, of being able to fight that law was something that hadn’t occurred to anybody. What we were doing, we were finding ways and means to accommodate to the law. And this is what the society was doing. It was attempting to accommodate that law.

One of the important things that the Mattachine does, which it has never been given credit for, and I think it should be, one of the first series of discussion groups we had was that we were very dissatisfied with the name “homosexual,” because it didn’t describe how we felt and what we were doing. What it really, all it kept, we ourselves knew that the moment you mentioned “homosexual,” the law, the judge, the lawyers, everybody said, “Oh, we know what a homosexual is,” and they read up what a homosexual is out of the penal code.

EM: Which means, which is…?

HH: Which is, uh, that you are a hetero performing nasty acts. That you are a hetero, and you’re a deviant, perverted hetero, but hetero you are. And this we wanted to change, because this didn’t speak us at all. So, consequently, we worked for about six months trying to find an acceptable word. I can remember, we’d have meetings every couple of weeks on just this thing alone. And I would come in with a whole list of a prefixes and a whole list of suffixes and we’d try putting the two together and see how it sounded. How it felt.

EM: Do you remember some of the alternatives?

HH: I forgot now what they all were. But eventually we ended up, decided that we liked “homophile.” That was the one we liked. Now, everybody said, “Well, they were using it in Holland, how come you didn’t copy it from them?” Well, fine, except we didn’t know that, because literature like that was not permitted through the mails, and the only way that you could have known that is if we had people of the upper middle class who were traveling in 1948 and ’49, and we didn’t know too many people who did, who would have gone to Europe and found this out and come back and told you.

Because this is the only, that was the only transmission for information of that sort. We would get, after, after we got our discussion group started and there were people who came to them, and then, or who were Europeans who were here and would write back to us, we would get little billets-doux from the post office saying, “We just received this package in your name. We want you to know that we’ve destroyed it.” And that would happen over and over and over again. People are trying to send us books or pamphlets and they would be stopped.

EM: And what kind of note would you get?

HH: From the post office.

EM: What did it say?

HH: Telling us that a package had come from England from so-and-so in our name, and it was illegal and unlawful material and it had been destroyed.

EM: So the fact was you couldn’t receive things through the mail that had any homosexual orientation.

HH: No, not at all. We couldn’t… Any homosexual orientation at all. No pictures. No nothing. Books couldn’t come, pamphlets couldn’t come, and if letters came, sometimes even the letters were intercepted. The letter would have been opened, and closed up again.

EM: And that wasn’t illegal?

HH: As far as the post office is concerned? Don’t be silly! The post office is the law! Or at least as far, as far as a little queer in L.A. is concerned, it’s the law. Because nobody’s going to fight your case for you.

EM: That’s right. That’s right. There’s nobody to fight the case.

HH: That’s right. These are the things you must understand. This is why I say there was no identity. It doesn’t exist. You’re a hetero performing nasty acts, so, therefore, therefore you’re a criminal.

EM: You were a deviant.

HH: You’re a criminal. I mean deviant sounds pleasant, but you’re a criminal.

EM: I mean you, to be a deviant, it means you must, you, if you’re a normal homosexual, you’re not a deviant, but since…

HH: What?

EM: If they considered homosexuality to be a real thing…

HH: Then you wouldn’t be a deviant.

EM: Because you were normal, but you’re a deviant heterosexual is what you’re saying. I never thought of that, and that’s exactly what it is.

HH: You were a deviant heterosexual and in that respect, this is unlawful.

EM: Homosexuals weren’t even recognized as a thing.

HH: It’s an adjective, it isn’t a person. We make a person out of it.

———

EM: You might just have heard something click for me. Thirty years ago, sitting with Harry Hay, I started to understand what he was up against, what we were up against in forming an identity and a movement in the mid-20th century. How do you fight for your rights if you don’t exist—if what you are is just a criminal act? Harry not only co-founded an organization to fight for our rights. He also helped shape who we are as a people.

So if an image of Harry Hay’s mother sipping tea while listening to a group of gay people discuss the Kinsey Report sounds meek, it wasn’t. It was subversive, it was radical, and risky in a way that many of us living our lives out and proud find hard to imagine. Harry Hay was one tough sissy.

Making Gay History is a team effort. Thank you to executive producer Sara Burningham and the rest of the Making Gay History crew: producer Josh Gwynn, production coordinator Inge De Taeye, social media producer Denio Lourenco, photo editor Michael Green, and our guardian angel, Jenna Weiss-Berman. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. Season four of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, and our listeners, including a generous gift from Andra and Irwin Press.

If you like what you’ve heard, tell your friends or give us a shout-out on social media. Find us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Tumblr. And to find out what we’re cooking up next, subscribe to our newsletter. You can find the link for that and all our previous episodes, as well as archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people we feature at makinggayhistory.com.

Just one more thing. Going forward, we’ll be sharing a new episode with you every other week. So we’ll be back in two weeks.

So long! Until next time!

———

###