Billye Talmadge

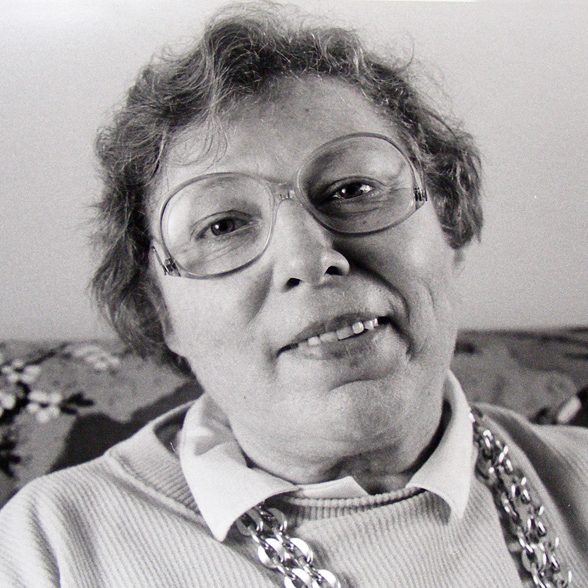

Billye Talmadge, 1990s.

Photo courtesy of Suzanne Deakins.

Billye Talmadge, 1990s.

Photo courtesy of Suzanne Deakins.Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: I first learned about Billye Talmadge when I began my research for the Making Gay History book back in the late 1980s. When I subsequently met and interviewed Billye, she taught me an important lesson. What I learned from reading about Billye, who was an early member of the Daughters of Bilitis—the first organization for lesbians in the United States, which was founded in 1955—made me think she was what some LGBT historians have called an “accommodationist.”

Billye earned that label because in the early days of the movement, DOB encouraged its members to wear traditionally feminine clothing (skirts, not fly-front jeans) that didn’t make them easily identifiable as lesbians.

This is the tricky thing about looking back on history through a contemporary lens—it makes it easy to criticize early activists over goals and tactics, because most of us don’t know nearly enough about what the world was like, what the context was, for their actions and decisions. At the time I interviewed Billye, I knew next to nothing about her life, but based on that contemporary lens I’d made assumptions about Billye “the accommodationist.” I couldn’t have been more wrong.

Casting aside my contemporary lens, I came to discover what Billye and the other courageous women on the front lines in the 1950s and ’60s were up against and how they nonetheless built a fledgling movement that provided a solid foundation for so much that came after.

Exploring the links below you’ll discover just some of ways in which Billye challenged the prevailing prejudice against lesbians and how she moved the ball forward at a time when a woman wearing fly-front jeans could face arrest or worse.

Please note that for her inclusion in the Making Gay History book, Billye asked me to alter the spelling of her name to protect her identity. She said, “I’m not using my real name for this interview. If we were not living on my salary, I wouldn’t care about using my real name. I would not be fired on the spot if they found out, but it would be made so difficult for me that I would have to quit. That’s the usual way now, because you can fight this kind of discrimination. But what you can’t fight is the way they get around it and make it so god-awful that you say, ‘Fuck it!’ and quit. And financially at this point in time, I can’t. That’s the only reason I’m not using my name.”

———

Read a brief biography of Billye Talmadge in this proudqueer.com article by Billye’s friend Suzanne Deakins. A short obituary of Billye appeared in the Bay Area Reporter.

Billye Talmadge’s oral history can be found in Eric Marcus’s book Making Gay History.

Watch a May 12, 1987 interview with Billye Talmadge from the Lesbian Herstory Archives’ Daughters of Bilitis Video Project.

Check out Beyond the Mist, a book of Billye’s musings and poetry, here.

For an obituary of Marcia Herndon, Billye’s longtime partner, go here.

To learn more about the Daughters of Bilitis, read Marcia M. Gallo’s Different Daughters—A History of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Rise of the Lesbian Movement and be sure to listen to our episode with DOB co-founders Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, too.

For information about The Ladder, the magazine of the Daughters of Bilitis, read Malinda Lo’s AfterEllen.com article. And take a tour of a GLBT Historical Society exhibit about The Ladder in this video.

As Billye mentions in the episode, the Daughters of Bilitis held its first national convention in San Francisco in 1960. Have a look at this DOB newsletter in which they announce the convention.

The episode talks about the risk of arrest for male impersonation faced by women wearing fly-front jeans. In our MGH Shirley Willer episode, Willer, who was the one-time president of DOB, talks about how wearing masculine attire made her the target of police brutality.

In Billye’s episode, Billye explains how your teaching certificate could be revoked if you were suspected of being a communist or a homosexual. This makes reference to what’s become known as the Lavender Scare, which was the gay analog to the 1950s Red Scare. The Lavender Scare is chronicled in a 2004 book by David K. Johnson called The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government. Read a summary of the book here. A new documentary called The Lavender Scare deals with the same subject; watch the trailer here. And check out our episode with Hal Call of the Mattachine Society, too.

During season two we heard from Herb Selwyn, a lawyer and ally, who said even hairdressers faced the prospect of losing their licenses to work and financial ruin if they got caught up in a legal system that criminalized same-sex love.

Perceiving “a real spiritual aridity” in the gay community, Billye became one of the co-organizers of a conference that led to the founding of the Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH) in 1964. CRH brought together progressive ministers and local gay rights groups with the goal of educating San Francisco’s religious communities about discrimination and anti-gay violence. For more information about the Council on Religion and the Homosexual, listen to our episode featuring Herb Donaldson and Evander Smith. And have a look at an exhibit about the Council on Religion and the Homosexual mounted by the LGBT Religious Archives Network.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History!

Billye Talmadge was an educator. Over the course of her life she was an elementary school teacher, accumulated two Ph.D.’s in education, and won awards for her work with blind and deaf children. But for most of her working life, who she was threatened what she did.

Billye brought her passion for education to her activism when she joined the first lesbian rights organization in the U.S., the Daughters of Bilitis, in the mid-1950s. Billye did everything from counseling women who had been thrown out of the military to holding “gab ’n’ javas” in her own living room. That was the 1950s version of a consciousness-raising group.

DOB offered Billye the chance to provide a new generation of women with the answers she herself had so desperately sought as a young woman coming of age in the 1940s.

But if anyone had found out about Billye’s work with the Daughters, she could have been fired from her job. When I interviewed her in 1989, she asked me to intentionally misspell her name for my book to conceal her identity. She was still worried about losing her job if her colleagues found out she was a lesbian.

Here’s the scene: Billye Talmadge is in her early 60s and lives with her partner, Marcia Herndon, and their three cats—two enormous calicos and one tiny kitten—in a small house in what was a rough neighborhood across the bay from San Francisco.

Billye is sitting at her dining room table. She’s heavyset, with short reddish-blond hair. She laughs easily and speaks with the excitement of a pioneer recalling the early days of her life in the movement. Billye lights a cigarette before explaining how she came to be a crusader for lesbian rights. But first she had to come to an understanding of her own identity.

———

Billye Talmadge: Cali, Cali, Cali, come…

Eric Marcus: I’ll get her as soon as I attach…

BT: If you give me that string over there, I can play with it and…

EM: I’m gonna see if she’ll sit in my lap.

BT: I don’t think she will…

EM: Interview with Billye Talmadge. Sunday, August 6, 1989. At the home of Billye Talmadge and Marcia Herndon in Richmond, California. That’s the San Francisco Bay Area. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

BT: I was always a tomboy, and I had had crushes, you know. And I had tried things with boys, and they just simply were not my cup of tea. I mean, I was uncomfortable. And I decided, If this is what it’s gonna be, I’m gonna know what one is supposed to do in this sort of business. So I had heard that there was this big dyke on campus.

EM: Where was this? Which school?

BT: This was in Kansas. And so I followed her for days. And so finally I saw her coming out of a cafe just off campus there going to her car, and I went up to her, and I said, “Well, I want to talk to you.” I’m sure I came on just that strong. And she sort of looked at me. And she said, “Well, okay, get in the car.” We got in and she started driving. And she said, “What is it?” And I said, “Well, I’ve just found out that I’m a homosexual and I want to know what this is all about.” I said, “I want to know how to make love to a woman. I never have and I think I better know.” And she looked at me and she kind of chuckled and she said, “Well, there’s only way to really show you.” And I said, “No, don’t show me, tell me.”

And so, we drove out somewhere. And we parked in a park, and I asked her every question I could think of. And she would answer to the best of her ability anything that I put to her.

And I think maybe somewhere along in there, when I look back on that particular scene, I think I knew then that, that there had to be questions like this that everybody was asking. And that somewhere, somehow there should be people who could answer as honestly as they could.

EM: At that time, this was 1950–51?

BT: Oh, no, this was, this was ’47, ’48.

EM: So there wasn’t… There was no one to call. And it was probably dangerous to be known, I assume.

BT: Absolutely. You could be thrown out of the campus in nothing flat.

EM: Let’s go back to when you first came in contact with DOB. How did you hear about DOB?

BT: I was with Jaye Bell. I know her as Shorty.

EM: Well, we’ll call her “Shorty” from here.

BT: She and I had moved down from the Tacoma-Seattle area.

EM: You were a couple by then.

BT: Yeah. We came down into the Bay Area. In fact, we were in Berkeley. And somebody we had met had been invited to this gathering at Del and Phyl’s, this buffet dinner or picnic type thing. And they ended up not going and Shorty and I did. But that was my first contact. And because I was… Both Shorty and I were so very impressed with Del and Phyl, and what they were trying to do. And it was another thing of, like a real interrogation. They were sitting there in the kitchen and we were just firing questions like crazy. And, but we both became very interested in it and just moved right in to…

EM: What interested you in that?

BT: The education, primarily. And the fact that there was the possibility of really, really helping people.

EM: Weren’t you concerned at that point about your job?

BT: No. [Laughs.] I look back on it, you know, and I don’t honestly know that I would have the guts now. I was a public school teacher at the time.

EM: This is the 1950s.

BT: Yeah.

EM: Where were you teaching?

BT: In Berkeley public schools. At that point of time, there were, there was a list of about 21 things that you could lose your teaching certificate for. The first one was to be a card-carrying communist. And the second one was to be suspected homosexual.

EM: Just suspected. They didn’t have to prove anything?

BT: They didn’t have to prove anything.

EM: And for you, for any professional woman, for any teacher, a bar was out of the question, wasn’t it?

BT: Yes, yes. At that point of time, to go to a bar was just sticking your neck in a noose. But there were house parties. This was one of the main reasons that the Daughters existed was, number one, in San Francisco at that point of time was to keep our kids out of the bars, because they were being raided and raided and raided and raided. And when we branched out a little bit, we had this chapter in Chicago. And two of our women were picked up and arrested on the streets for wearing fly-front jeans. They were arrested for impersonating males. That’s all that they had, was fly-front jeans. But they were picked up and arrested as impersonating a man.

EM: What could you do for them?

BT: Well, help them to know their rights. Number one, in most states you had to have more than one apparel to be impersonation and, two, unless they were soliciting or anything, or doing something other than that, other than the fly-front jeans, you know, to call a good lawyer, plead not guilty, and demand a jury trial.

They had no women police on the forces, and women, when they were stopped or picked up or whatever it—, were… I know of one person particularly… In fact, one of our DOB people was beaten to a bloody pulp.

EM: By the police.

BT: By the police. She was drinking and she was drunk, but she was beaten because she was a goddamn dyke and that was quoted again and again by the guy who was beating her to, you know…

EM: You sound very protective of DOB members, when you said you… Keep the kids out of the bars. I get a sense you had great concern.

BT: Well, we had a lot of kids too, see. You had to be 21 to be in DOB, but we had a lot of 17-year-olds, and they would come and they would call and they would try to, you know… And we couldn’t touch them legally because that was one way that they could get us.

EM: “They” meaning?

BT: “They” meaning the law. Because this then was still contributing to the delinquency of a minor. And that was seven years state pen.

EM: What could you do for the kids then? For the, for the young ones?

BT: We had house parties. They were not, they were not DOB things, and we, they did not drink, we would not let them drink. They had soda pop, they had Cokes.

EM: Really?

BT: Well, see, my my first and foremost punch was education and in any way whatsoever that we could achieve this and first and foremost of our girls. We had, we had one gab ’n’ java session for instance on, I can’t remember what it was, but how to make a butch into a dolly, or, you know, I mean something weird, but how to show, how to accommodate to a situation. So accommodate in that regard, if the, if the situation arose…

For instance, in our very first national convention that DOB had—we had it right here in San Francisco—and we had one woman who called us from Los Angeles area. She had been a subscriber and a member of DOB for several years. We’d never met her, we’d had a lot of correspondence from her. She had never been in a skirt in 17 years. She said, “Do we have to wear skirts?” And we said, “Yes, you have to wear a skirt.” And so she went out and she bought one skirt. She had several different men’s shirts to go with it. I didn’t care about the shirts, nobody else did. But she had to wear a skirt.

EM: Why?

BT: Honey, the law was still on the books that you could be arrested as a male for fly-front jeans.

EM: That’s a good reason to encourage her to wear a skirt.

BT: And that was the only reason. And, and if we had, and we had quite a number of people at our first convention. And if we had, you know, and we had police there, too, and they scanned every one of us. And I’m sure that Del and Phyl and I and a number of others were on the books to be watched.

EM: By the police. So this was a survival tactic to wear women’s clothes.

BT: Absolutely. Absolutely. And this was rough, too, because we wanted to bring our people together. And we wanted to have a convention. But we wanted to protect our people, too. We didn’t want to put them in jeopardy, and everything we did placed them in jeopardy, and they knew that. They did know that.

EM: Ah, ah, ah. No chewing.

BT: Oh, oh, oh, oh. Sorry about that.

EM: I’ll scratch the head.

BT: Ah, okay.

EM: No blood.

BT: I’ll give you an example. I had a threat of blackmail. And, um…

[To the cat.] Nicki. Nicki.

Shorty and I had moved down from Seattle and there was a very, very dear friend of mine still up there in the Tacoma area. And I was working and had, at this point of time I was working for a drugstore chain, and was still, I had to get my credential cleared. I had a couple of classes that I had to take to be certified in California.

EM: This was 1953.

BT: Yeah. Anyway, Shorty and I had met this woman here in the Bay Area, whom we liked very much, and I thought this was the perfect match for my friend in Tacoma, and so I started a communication between them, and I matched and I was good because they just celebrated their 30th anniversary.

EM: That’s a hell of a match.

BT: Yeah, I’m good. [Laughs.] And, but I had written this letter to Bonnie…

EM: In Tacoma.

BT: In Tacoma, and I, you know, I didn’t hear from her. What had happened was, Bonnie had gotten the letter, had read it just hurriedly, and had gone on to work, and apparently as she went out the door she dropped the letter, and the postman picked it up. And the postman then, because of my letter, which I had written on my company stationery, knew my name, my address, and where I worked.

EM: And he knew from the letter that you were…

BT: From the letter, obviously, that Bonnie was, too, was gay. And he proceeded to blackmail her on the basis of, if she didn’t provide him what he wanted, then he would see to it that I was blown all over the map. And I called her and I knew something was wrong. I didn’t know what. She said, “I can’t talk about it. I can’t talk about it on the phone.” And I said, “I’m coming up there.” And so I flew up there and found out what it was. And I said, you know, “Why in the hell didn’t you go to the police? Why didn’t you go to the post office? Why didn’t you do something?” She could not, felt she couldn’t because, and she said, “I want to, I want to work with this.” You know… “I think we’ll be alright.” She says, “I think I can persuade him and talk to him.”

And I was livid. I flew back the next day, I had to, but I was so angry. I wasn’t frightened. I was too angry to be frightened. So come Monday morning, I looked up “FBI” in the phone book. I don’t know anything else. You know, FBI was what came to my mind. I took my lunch hour and I stomp down to the FBI. There was no one home. The door was… And the door happened to be, I mean the office happened to be the upstairs in the post office in Oakland.

So I stormed down to the postmaster general in Oakland, and I said, “I want to talk to somebody about blackmail.” And he said, “What do you mean?” And I said, “I want to talk to somebody about a postal carrier who’s trying to blackmail me,” and he said, “My God, in my jurisdiction?” And I said, “No, the guy happens to be in Tacoma.” And he said, “Just a minute.” So he waltzed me over to the postal inspector.

And this was an education in itself because the postal inspector went all the way around the barn to say, you know, “What was in this letter?” He said, “Okay, let me ask you this.” He said, “Does the word ‘homosexuality’ enter the letter?” And I said, “Yes, it’s there, but,” I said, “it’s nothing that’s wrong.” And he said, “Let me ask you this, could my 16-year-old daughter read this letter? Would I allow her to?” And I said, “Yes,” and I said it would probably educate her but it would not harm her. And he said, well, the difficulty is that, this point of time nobody had ever come up with any definition of what was pornography, and using the postal department in this regard was, you know, tricky.

He said, “Now, again, is there anything in this letter that could not be read in court?” And I said, “Yes, it could be read in court, and I wouldn’t be afraid for it to. I would be embarrassed perhaps, but I would not be afraid.” And he said, “Okay, you let me handle this.”

The postal inspector in this, in Oakland area, contacted the postal inspector in the Tacoma area, and they landed the guy right smack on his ass. And so what happened was, he was, the man was confronted with it. He confessed, and he got three years.

EM: In jail?

BT: He certainly did, because the letter belongs to the writer until it’s dropped in the post office box. Then it belongs to the government. Once it is delivered, it is the sole property of the addressee, and anybody tampering with it tampers with the federal government. And anybody trying to use such an item in a blackmail situation that has gone through the post office, then they’re the ones who have committed the crime, not anybody else.

EM: And it becomes a federal crime.

BT: That’s right, and he spent three years in prison.

EM: Ever hear from him again?

BT: No.

EM: What an experience. Boy, were you gutsy.

BT: I was angry. Okay, and this was, this was the driving force, I think, of the very beginning of us in DOB. We were angry with what of the injustices that we saw. And our anger on those issues made us totally forget any fear. This is the only thing that drove us. I know.

EM: Um, thank you for your afternoon… and for the company of your cats.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: Maybe I wasn’t being completely honest when I thanked Billye Talmadge for the company of her cats—their new kitten was a cutie, and I could understand why Billye and Marcia had taken it in after neighborhood kids had beaten it. But the big calicoes took more than a few swipes at me, and seemed to think that the foam covers on the lapel mics were cat treats.

The blackmail story that Billye shared with me wasn’t the first I’d heard; extortion under the threat of exposure was a persistent fear going way back. You heard in our recent episode about Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld how blackmail overshadowed gay life in Berlin—and helped inspire him to found the first gay rights organization in the world back in 1897. That fear of blackmail was something the early organizations in the U.S. had to protect their members against. It was one of the reasons so many people in the early movement here used pseudonyms.

Billye mentioned the police “scanning” the first Daughters of Bilitis convention in 1960. The authorities had organizations like DOB and the Mattachine Society under surveillance. At one point the San Francisco police broke into, and searched, the Daughters’ headquarters and the FBI infiltrated DOB meetings. An FBI report from 1959 states that “the purpose of the DOB is to educate the public to accept the Lesbian homosexual into society.” That sounds about right.

After we decided to feature my 1989 interview with Billye in this season of Making Gay History, we worked on finding out what had happened to her in the years since. We came across an email address for her primary caregiver, Suzanne Deakins, and wrote to her. The next day, October 24, 2018, Suzanne responded to us. Her email said: “Billye Talmadge passed this morning at 7:25 a.m. Pacific time. It was a peaceful passing.” Billye was a few weeks shy of her 89th birthday.

Suzanne, who was also Billye’s dear friend of five decades and her one-time partner, told us that when Billye’s health began declining, she moved Billye to Portland, Oregon, where Suzanne lives, and where Billye spent the last five years of her life. A small community of friends fundraised for her and kept an eye on her.

When I spoke with Suzanne, she said Billye had taken special pride in the fact that gay people could live so much more openly than when she was young. Her hard work had paid off. But, as we all know, there’s still plenty to do.

———

Making Gay History is a team effort. Thank you to executive producer Sara Burningham and the rest of the Making Gay History crew: producer Josh Gwynn, production coordinator Inge De Taeye, social media producer Denio Lourenco, photo editor Michael Green, and our guardian angel, Jenna Weiss-Berman. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

A special thank-you to Billye Talmadge’s friend Suzanne Deakins for sharing her memories and photos of Billye.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. Season four of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, and our listeners, including a generous gift from Andra and Irwin Press.

There’s a new way you can support Making Gay History. Click on the merchandise tab on our website and you’ll find Making Gay History t-shirts, tank tops, and hoodies. We’ve also got Making Gay History tote bags, and mugs. So you can wear us, carry us, drink with us, and at the end of the day, lay your head on a pillow that says “I Am Making Gay History.”

If you like what you’ve heard, tell your friends or give us a shout-out on social media. Find us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Tumblr.

And to find out what we’re cooking up next, subscribe to our newsletter. It’s easy. You can find the link for that and all our previous episodes, as well as archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on Billye Talmadge, Marcia Herndon, and each of the people we feature at makinggayhistory.com.

So long! Until next time!

###