Magnus Hirschfeld

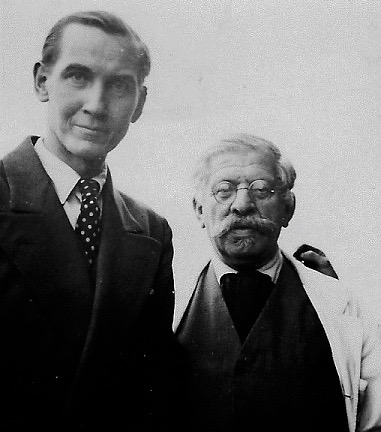

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, 1927. Credit: Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V., Berlin.

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, 1927. Credit: Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V., Berlin.Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: When I wrote the original 1992 edition of Making Gay History (which was then called Making History), my oral history book about the LGBTQ civil rights movement, I devoted just one paragraph to Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld’s work in the opening to the first chapter:

“More than four decades before World War II, the first organization for homosexuals was founded in Germany. The goals of the Scientific Humanitarian Committee, as the organization was called, included the abolition of Germany’s anti-gay penal code, the promotion of public education about homosexuality, and the encouragement of homosexuals to take up the struggle for their rights. The rise of the Nazis put an end to the Scientific Humanitarian Committee and the homosexual rights movement in Germany.”

And that was it. Not even a mention of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld himself or his sexuality institute, which he founded in 1919. Considering that the focus of my book was the gay rights movement in the United States, that’s not so surprising. But given what I’ve come to learn about Dr. Hirschfeld and his pioneering work, as well as his influence on the founding of the movement here in the U.S., I’m sorry I didn’t at least include his name!

So as you can hear in this episode of Making Gay History, three decades after I first started conducting interviews for my book, Sara Burningham, Making Gay History’s executive producer, and I took a deep dive into the life of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld. That included traveling to Berlin in May 2018 for the huge celebration in honor of the 150th anniversary of the birth of Magnus Hirschfeld, interviews with Magnus Hirschfeld experts, an interview with a Canadian pack rat/citizen archivist who saved a suitcase full of long-lost Magnus Hirschfeld belongings, and a reenactment of Hirschfeld’s 1918 silent film, Different from the Others. If reenacting a silent film in a podcast sounds like an impossible task, well, Sara Burningham figured out how to do it brilliantly.

As we traced the threads of history back in time, I came to discover that one of the threads of Magnus Hirschfeld’s history came back to the present day and had a direct connection to our Making Gay History family. Here’s the story. Before I left for Berlin, I found out that our photo editor, Michael Green (who also happened to be the original publicist on the Making History book back in 1992), was going to be in Berlin with his partner, Ilan Meyer, too. Ilan was heading to Berlin for a family reunion.

It wasn’t until Michael and I were having lunch after our tour of the Schwules Museum and we were waiting for Ilan to join us that I discovered the reunion Ilan was attending was for Magnus Hirschfeld’s family, which had been decimated during the Holocaust and the survivors scattered across the globe. Turns out Ilan, who grew up in Israel, is a cousin of Magnus Hirschfeld.

In the photo below you can see Ilan on the left, his cousin Ruth Gabrielle Cohen, who is Magnus Hirschfeld’s niece, and Michael Green on the right. They’re standing against the back of the Hirschfeld monument in the Charlottenburg neighborhood of Berlin where there had just been a wreath-laying ceremony.

One of the things I love about following the threads of history is that you never know where they’ll lead you.

To learn more about Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, a true hero of the LGBTQ civil rights movement, have a look at the information, links, photos, and episode transcript that follow below.

———

On the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld’s birth in May 2018, Gay City News published this overview of his life and work. To learn more about Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, check out Ralf Dose’s biography Magnus Hirschfeld: The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement. While no recordings of Hirschfeld’s voice remain, here is a silent video snippet of Hirschfeld at work.

For information about the two loves of Hirschfeld’s life, check out this Hirschfeld Institute entry on Karl Giese and this Xtra article about Li Shiu Tong.

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project has an entry for Magnus Hirschfeld’s trip to New York City in 1930 when he stayed at the New Yorker Hotel at the start of a three-month lecture tour of the U.S. Have a look at several photos and images related to that trip.

Find out more about the Eulenburg Affair, which kept Germany spellbound from 1907 to 1909, here. Hirschfeld’s involvement as a court-appointed expert in the Eulenburg Affair drew the attention of cabaret singer Otto Reutter, whose “Das Hirschfeld-Lied” you can hear in its entirety here.

Another prominent trial the episode mentions is that of Oscar Wilde—a trial that was the subject of the film The Trials of Oscar Wilde, starring Peter Finch as the playwright. You can watch the whole film here. You can also learn about the life and work of Oscar Wilde on the website of the Oscar Wilde Society.

Watch a reconstructed version of the 1919 silent film Different from the Others here. Find out more about just how groundbreaking the film was in this featurette by Jeffrey Schwarz.

For an account of the birth of the gay rights movement in Germany, read Alex Ross’s “Berlin Story” in the New Yorker.

Learn more about the vibrant gay scene in Berlin during the Weimar years in Terry Gross’s Fresh Air interview on NPR with Robert Beachy, author of Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity. You can hear the era’s gay anthem “Das lila Lied” (“The Lavender Song”), as sung by Marek Weber, here. Go here for the lyrics and background information.

Adam Smith, the Canadian man who found Li Shiu Tong’s suitcase with, among other things, Hirschfeld’s death mask, recorded the moment when Ralf Dose of the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft first laid eyes on the treasure at Smith’s Vancouver apartment. You can watch clips of the video here.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

If you’ve listened to our first three seasons, you know what to expect from a Making Gay History episode: we explore LGBTQ history guided by the voices of the people who lived it.

I’m afraid that’s not going to be possible this week. You see, I’d like to share with you the story of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, the founder of the world’s first gay rights movement, who, more than a century ago, put his life on the line to stand up for LGBTQ people. Hirschfeld said, “Soon the day will come when science will win victory over error, justice a victory over injustice, and human love a victory over human hatred and ignorance.” And the reason I read that quote aloud rather than just playing you archival tape is because all recordings of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld’s voice have been lost. But by following his words, and his work, we’re going to tell you his story.

This past spring, I traveled to Germany. I hoped to track down some little-known pieces of LGBTQ history—at least little known to me—and to meet some of the history detectives working to reconstruct a scattered legacy.

So here’s the scene. Berlin, May 2018. I’m in Charlottenburg, an upscale neighborhood in the western part of the city. I’m with a group of scholars, researchers, and relatives of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld. We’ve come together to honor the 150th anniversary of his birth. Here, in front of where Hirschfeld once lived, a monument now stands. It’s a bronze pillar, topped with Magnus Hirschfeld’s unmistakeable face—bespectacled, with a bushy moustache. More reminiscent of a favorite uncle than a dangerous radical. But make no mistake. Hirschfeld’s life and work were revolutionary.

Ralf Dose, historian and director of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, steps forward and lays a wreath at the foot of the monument.

Magnus Hirschfeld was born in 1868 into a Jewish family in a town in the Prussian Empire that’s now part of Poland. He studied to become a physician and eventually moved to Berlin. When news of Oscar Wilde’s trial and imprisonment reached Germany, Hirschfeld was outraged. This was part of what inspired him to blaze a trail as a pioneering sexologist and gay rights champion. In 1897, when he was 29 years old, he founded the, uh… I’m gonna need some help with my German here…

Daniel Baranowski: Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee…

EM Narration: …or, as it’s known in English, the “Scientific Humanitarian Committee.” And that’s where it all began. The first gay rights movement in the world. Hirschfeld was gay, but closeted. That’s just how it was.

At the time, homosexual acts between men were illegal under paragraph 175 of German law, punishable by imprisonment. Hirschfeld and his newly founded committee got to work, lobbying for paragraph 175 to be repealed.

Dagmar Herzog: His aim is to decriminalize male homosexuality but also to combat anti-homosexual prejudice more generally.

EM Narration: This is Dagmar Herzog, distinguished professor at the Graduate Center at the City University of New York, and best known for her work on the history of sexuality.

Dagmar Herzog: So he runs a petition campaign, which gets thousands of signatures from prominent politicians, medical doctors, religious leaders. He also gives 3,000 public lectures to all manner of audiences. He starts a sexual medical journal in 1899 called “The Yearbook for Sexual Intermediaries,” which is highly respected among medical doctors.

EM Narration: Establishing himself as an expert on sexuality, frequently giving evidence in court, Hirschfeld argued that homosexuality was inborn, natural, and should not be punished. Here’s Rainer Herrn, a senior lecturer specializing in the history of sexology. He’s spent the last 30 years researching the work of Magnus Hirschfeld.

Rainer Herrn: He used his function as an expert widely, and he really, he was so clever in doing that, his enemies they raving mad because the courts believed Hirschfeld.

EM Narration: Hirschfeld’s fame as an expert turned to notoriety when he was drawn into Germany’s biggest gay scandal. The Emperor Wilhelm II’s closest confidant was accused of having an affair with a high-ranking general, sparking a scandal with wide-reaching political implications that set the stage for the first World War. Known as the Eulenburg Affair, it sprawled over three years of courts-martial, libel trials, suicides, blackmail, and imperial intrigue.

Kevin Clarke: For three years it was discussed in the German newspapers whether homosexuality is dangerous, whether it’s natural, whether it should be punished, how it affected the emperor, and so this went back and forth and back and forth…

EM Narration: Dr. Kevin Clarke of Berlin’s Schwules Museum, which roughly translates to the “Fag Museum”…

Kevin Clarke: And Hirschfeld was called as a witness, or as an expert, to talk about this, but because he became so famous because of those statements, one of the big cabaretiers, you know, pop singers, of the time wrote the “Hirschfeld Lied,” the “Hirschfeld Song”…

The “Hirschfeld Lied,” and it’s by Otto Reutter, he’s a very famous singer in that time… “Watch out, Hirschfeld’s coming, and he will see homosexuality everywhere. So beforehand you had two dogs just walking down the road, but now, you know, when they sniff each other’s butts, they have to watch out, because when Hirschfeld comes, he’ll say, ‘Oh, they’re perverts.’”

“Two men who were just, you know, supposedly regular friends, who like to hug each other, and go out together, and have fun, but now, you know, when Hirschfeld comes around the corner, they immediately start kissing their girlfriends or wives just to erase all possible evidence that they could be gay.” It’s quite a funny lyric and very typical of course for its time.

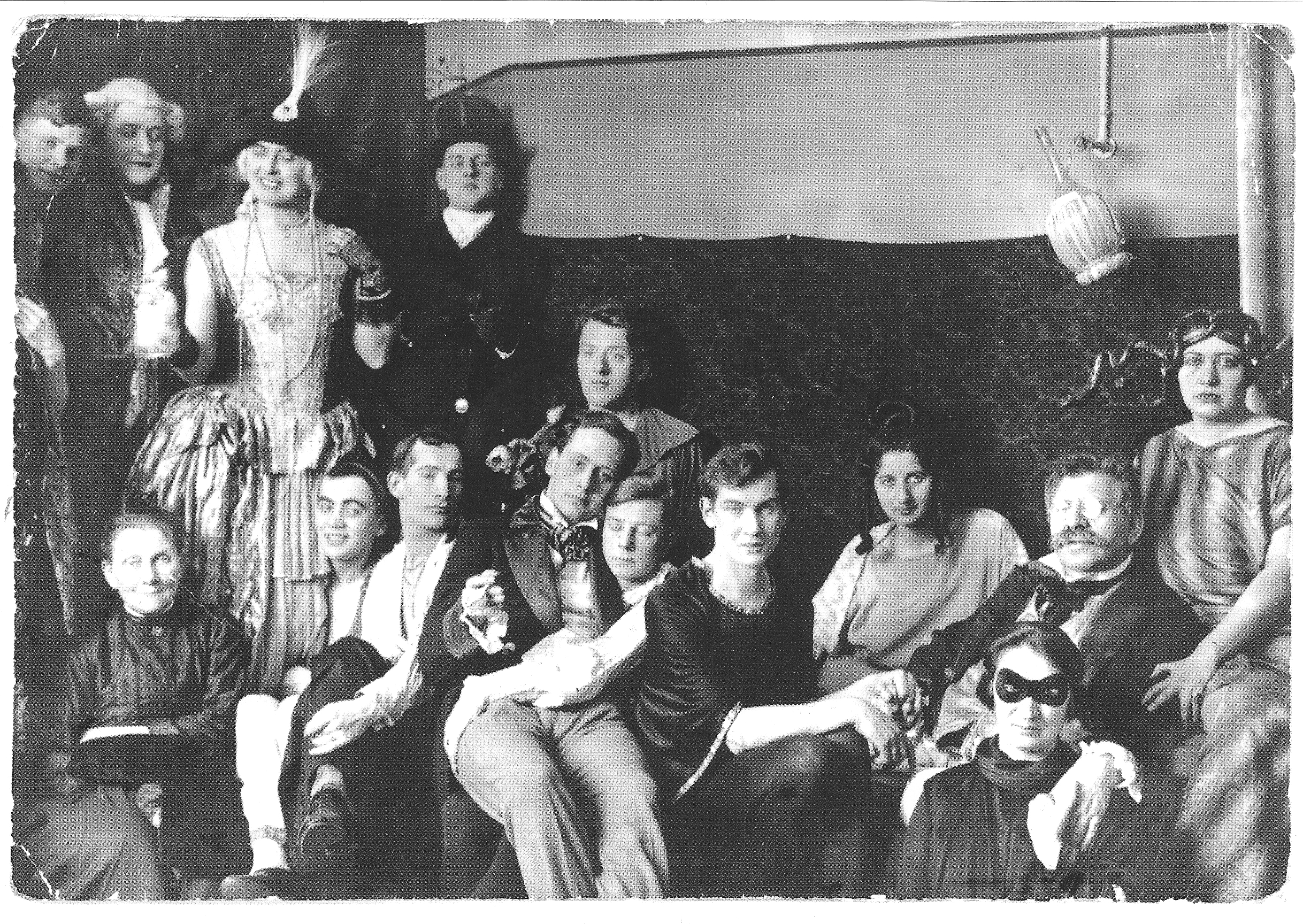

EM Narration: But the times were changing. After the First World War, the liberal atmosphere of the Weimar Republic ushered in an era of relative freedom in Berlin. By 1919, Hirschfeld had met one of the loves of his life, Karl Giese, and had helped create the world’s first film dealing with homosexuality.

EM Narration: I’m going to need some help with my German again. The film was…

Ralf Dose: Anders als die Andern…

EM Narration: … or, in English, Different from the Others. And I’m going to need even more help, because Different from the Others was a silent movie. So, with a little help from Dagmar Herzog, Rainer Herrn, and Ralf Dose, here’s Different from the Others.

Dagmar Herzog: It’s a love story between two musicians, two violinists, a teacher and a student.

EM Narration: Different from the Others is a tragic gay love story—a trope that, by the way, Hollywood’s taken a hundred years to get over.

Dagmar Herzog: In fact, the movie begins with the main character reading obituaries in the newspaper, which in veiled language are indicating that these were all men accused of homosexuality who had suicided, so that is the framing narrative.

EM Narration: An aspiring musician and his talented concert violinist teacher fall in love. The relationship is discovered and the couple is blackmailed.

Dagmar Herzog: Which was one of the major dramas in Berlin at that time. There were many male prostitutes who made their living by blackmailing adult men who were seeking homosexual acts.

EM Narration: As the blackmail pressure mounts, the young musician flees, and the older violinist is heartbroken. The blackmailer is relentless. The violinist pays him off, but the blackmailer vows to report him to the police. When the blackmailer is arrested, he accuses the violinist under paragraph 175, and they both end up in court together.

Dagmar Herzog: And in the midst of it all, Hirschfeld, who is the script writer for the movie, is also one of the characters in the movie. He is the good doctor who offers wonderfully affirming comments that same-sex love is a beautiful thing.

EM Narration: Hirschfeld, appearing as himself as an expert witness, pleads in court on the violinist’s behalf. The violinist is convicted but given a light sentence—just a week in prison. But the scandal has ruined him. He is shunned and his concert tour is canceled. Inconsolable, he takes his own life. The young musician hears of his former lover’s death, and is devastated. He, too, contemplates killing himself. But Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld appears again.

Rainer Herrn: And then Hirschfeld says, “Don’t do it, you have another task—you have to encourage future generations so they don’t suffer the same destiny as your lover did.”

EM Narration: Hirschfeld says, “What matters now is to restore honor and justice to the many thousands before us, with us, and after us. Through knowledge to justice!”

Rainer Herrn: In a way, it’s tragic, maybe you can say it’s kitschy, but at the end…

EM: Magnus Hirschfeld sent a message to the future.

Rainer Herrn: Yes. Yes, he did.

EM: And his message was not destroyed.

Rainer Herrn: No.

EM Narration: Hirschfeld was the expert on homosexuality—and he was a gay man. But as Ralf Dose, director of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, says, only one of those things was a public matter.

Ralf Dose: So he himself never came out in a way we would expect that, to say “I am…” And so you never find in his publications the word, “I am a homosexual.”

EM: Did he just live his life, then?

Ralf Dose: He led his life, he lived together with his boyfriend, everyone knew, uh, if everyone wanted to know.

EM: But it wasn’t spoken.

Ralf Dose: It wasn’t spoken.

EM Narration: That tentative openness was a feature of gay life in Berlin at the time. While homosexuality remained illegal, dozens of gay clubs were open and thriving. In 1920, Kurt Schwabach and Mischa Spoliansky wrote “The Lavender Song,” or “Das lila Lied.” Here’s Marek Weber’s recording of it.

He’s singing, “We are just different from the others who are being loved only in lockstep of morality.” The song became a gay anthem and was performed in the cabaret clubs around Berlin.

Dagmar Herzog again…

Dagmar Herzog: And it’s a city that sort of celebrates every possible predilection. I mean, the crucial thing about Berlin in the Weimar years is not the pervasiveness of people who are comfortable with their homosexuality and acting on it; it’s the visibility, it’s the proud visibility, and the glamor and the fun of it. And that already triggers conservative responses, even before the Nazis come to power, of two varieties: Christian-conservative, on the one hand, and right-wing thuggish Nazi, on the other.

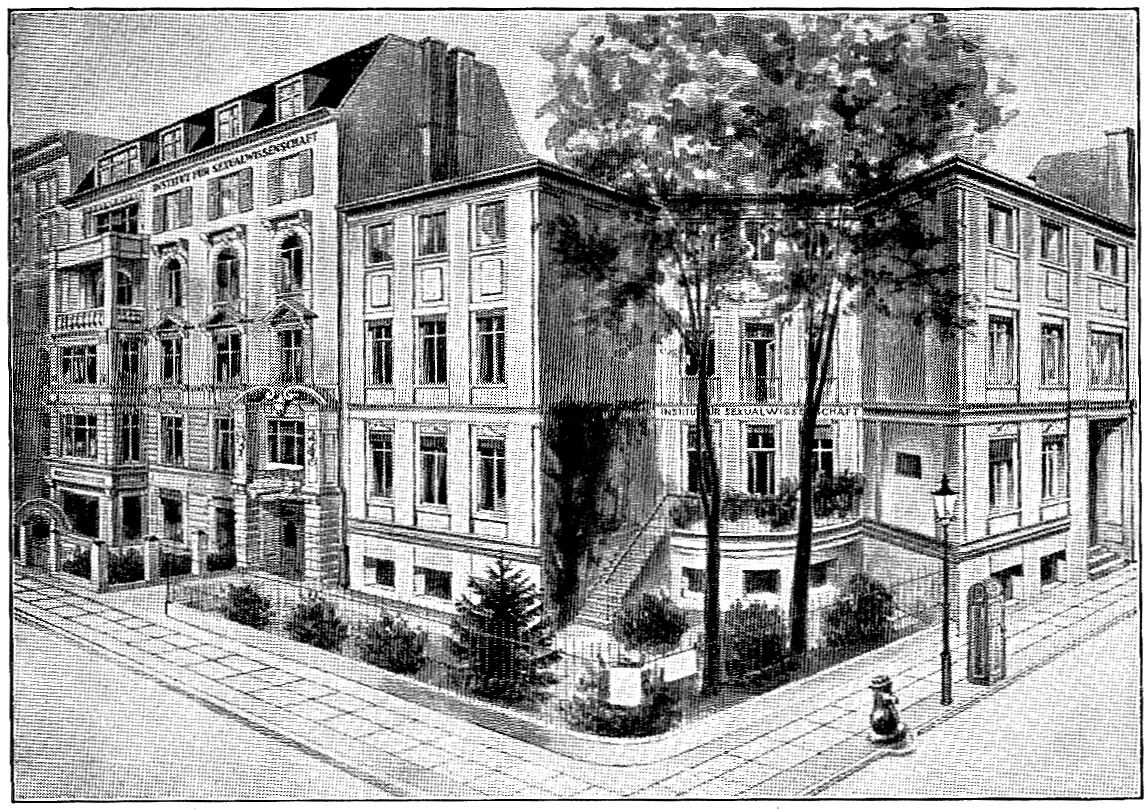

EM Narration: While the backlash built in the background, in the middle of gay Berlin—literally the middle—Hirschfeld’s institute opened its doors in 1919, on the edge of Berlin’s Central Park.

Dagmar Herzog: You have to imagine this building. It’s this gorgeous villa on the northern edge of the Tiergarten Park. And the Tiergarten Park also had cruising areas for gay men, so there’s kind of a logic to that location, but it’s also just this incredibly sumptuous place. The whole complex ends up having about 50 rooms.

I mean, it’s a huge thing. There’s a library with, I don’t know, by the end 20,000 volumes. There’s an archive, 35,000 photographs of every imaginable sexual predilection and possible way of being in gender expression terms. There’s an enormous amount of information about sexuality being collected there. There’s a lecture hall. There’s a question box, where people can go and put their little questions. And it turns out that he was also a huge resource for heterosexuals.

In fact, the majority of the questions end up being about contraception. And he was a major advocate for premarital heterosexuality as completely morally okay. He was their, he was an advocate for a morality of consent—you know, the idea that consent is sexy was his concept already then. He was an advocate for the idea that the state should get out of the private business of the bedroom. And he defended everybody’s sexual rights. And he advocated contraception. So all those things made him a real magnet for people who were interested in having happier sex lives.

EM Narration: Hirschfeld’s institute was also a magnet for visits from people such as Christopher Isherwood, W.H. Auden, and Lili Elbe, the trans woman who was immortalized in the film The Danish Girl.

Dagmar Herzog: So what we would now call gender alignment or gender confirmation surgery—some of the very earliest surgeries of that kind were conducted in Hirschfeld’s institute. He didn’t do the cutting himself, or the sewing, but he had doctors there doing it, and from 1920 on.

EM: But Hirschfeld’s profile and his beliefs made him a prime target.

Dagmar Herzog: He is the preferred hate object for the right wing and especially then for the Nazis. He is constantly reading slander. You know, you think you’re dealing with aggression on the Internet now, but, I mean, every morning he woke up and there was nasty, crappy, disgusting, anti-semitic stuff, above all, being said against him. And, you know, 1920, he’s at a lecture in Munich, and right-wing thugs beat him up and leave him for dead on the street. He’s bleeding. And then he’s reading his obituary the next morning. And luckily he’s still alive, but then there are many right-wing venues that say, “Oh, we’re really sorry that this poisoner of the Volk hasn’t died already.”

EM Narration: Despite the threats, the violence, and the slander, Hirschfeld persisted. Through the 1920s, his institute grew, and in the late 1920s Hirschfeld organized the first of several international congresses for sexual reform. The speakers were a laundry list of leaders in the nascent gay rights movements, the fight for women’s rights, and sexual science.

In 1931, while Dr. Hirschfeld was on a tour of the U.S., the Hearst newspaper chain nicknamed him “the Einstein of Sex.”

The Nazis set their sights on Hirschfeld early in their reign of terror. He posed a triple threat as a gay, Jewish socialist. As far back as 1920, Hitler had singled out Hirschfeld, calling him “Jewish swine.” When the Nazis swept to power in 1933, Hirschfeld’s library at the Institute for Sexual Science was their first target for book burnings. On the night of May 6, Nazi youth ransacked the institute—most of the contents of the institute were destroyed or stolen, and thousands of books were seized. Four nights later, stacks of volumes from Hirschfeld’s library went up in flames on the Opernplatz. The bust of Hirschfeld that had greeted visitors to the institute was tossed on the fire, too.

But Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld wasn’t in Berlin. He was in Paris, where a few days later he watched his life’s work reduced to ashes.

Ralf Dose: He writes that he saw the destruction of the institute with his own eyes on a newsreel in Paris.

EM Narration: By this time, Dr. Hirschfeld had been living out of suitcases for years. He had left Germany for a world tour in 1930. Along the way, he’d met the second love of his life, Li Shiu Tong, and for a while, the three of them—Li, Karl Giese, and Dr. Hirschfeld—lived together in a grand apartment on the Avenue Charles Floquet in Paris. But Dr. Hirschfeld’s health was fading, and in 1934 he moved to the sunnier, warmer climes of Nice. The following March, Hirschfeld named his two lovers, Li Shiu Tong and Karl Giese, as his sole heirs.

On May 14, 1935, Dr. Hirschfeld spent the morning with a friend and his great-nephew. It was his 67th birthday. They opened birthday letters together, then went for a walk and had lunch. Upon their return, Hirschfeld collapsed in the doorway to his apartment building. They somehow managed to carry him up the stairs to his apartment on the third floor, where he died. Dagmar Herzog again…

Dagmar Herzog: It’s pretty clear that he dies of a heart attack, but you could say of a broken heart.

EM Narration: It had been two years since the Nazis destroyed his institute.

Daniel Baranowski: It actually took some time, um, at least 20 to 30 years after the Second World War, that people began to commemorate Magnus Hirschfeld. He was completely forgotten.

EM Narration: Dr. Daniel Baranowski is from the Magnus Hirschfeld Federal Foundation, an anti-discrimination organization founded by the German government.

Daniel Baranowski: The very good thing that the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft, the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, did is that they begin, at the end of the 1970s, to do research on him and collect materials, archival materials.

Ralf Dose: When we started our work, everyone said, “Well, that will be in vain. There’s nothing left, the Nazis destroyed everything, everything was burned. There’s no one left who can tell you anything.” And, well, that turned out to be wrong.

EM Narration: That’s Ralf Dose again, the director of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society. He’s devoted almost 50 years to researching Hirschfeld’s life and work. Ralf and his colleagues have worked tirelessly to find the scattered remnants of Hirschfeld’s legacy, some of which was lost forever following the suicide of Karl Giese in 1938, and the subsequent deportation and murder of his heir by the Nazis.

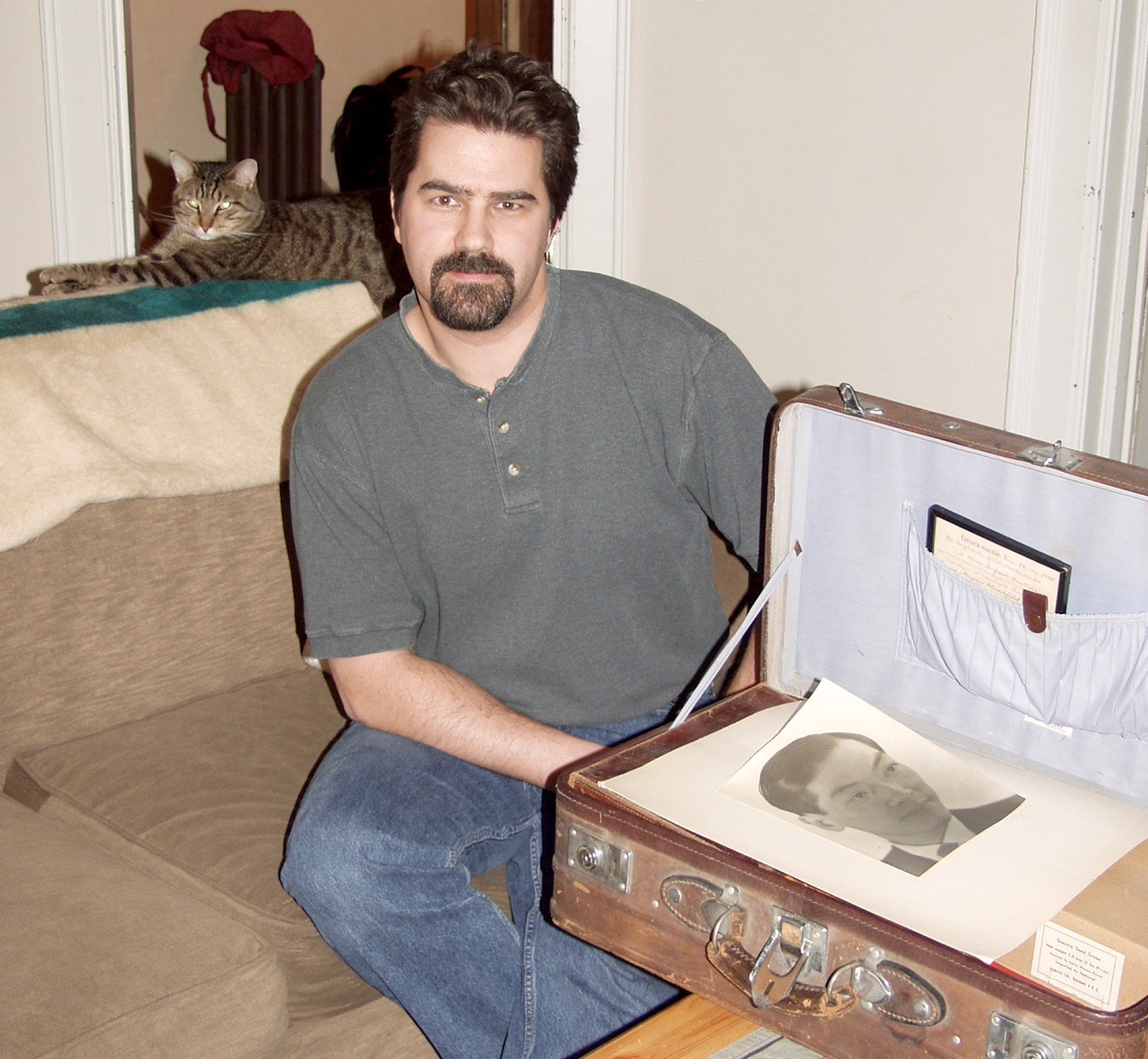

For Ralf Dose, this detective work has included early mornings, late-night Internet sessions—messages that travel through time—and the serendipity of a Canadian pack rat who stumbled upon history at the bottom of a garbage chute. That self-described pack rat is Adam Smith, of Vancouver, British Columbia.

Adam Smith: I had a rather unusual job at the building I used to live in. It was my responsibility to drive a dumpster from the bottom of a parking garage out to the back of the building every week. So one day I open the door, and I walk into this small airless, windowless room with a garbage dumpster in it, and I find a collection of leather suitcases. Beautiful old leather suitcases. And then I opened up one suitcase.

And amongst the other things in it was a leather box. I lifted the lid and saw something I’d never seen before, but I knew exactly what it was the moment I looked at it. The mask felt smooth and cool, um, kind of everything you might imagine if you let your imagination run a little wild on the notion of a death mask. I didn’t know who Hirschfeld was, I had no idea who this person was, or why these things ended up in the basement of a parking garage in Vancouver, Canada. At the time I think the feeling that was overwhelming me was just curiosity more than anything else and this kind of a sense of distant drama. And I carried this one suitcase packed full of stuff with me to Toronto when I moved there, and it went into the storage room in Toronto, and it sat there for many, many years.

Ralf Dose: One drunk night, when I was doing some research on the Internet, just searching for the name of Magnus Hirschfeld, and I pushed wrong buttons, and the result was that I got a, very oldest entry was on top, so that’s not the way you use the Internet normally.

Adam Smith: So I think it was, I think it was 1993 and this is before the world wide web, but I was on the Internet at that point, and there was a thing called Usenet News, which was kind of a precursor to forums. So I posted a message saying, “I’m looking for information about Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld. Can anybody tell me who he is? I have some things that may be significant about him.”

Ralf Dose: Then there was a name, signed by Adam Smith. At the end of that night I found an email that might lead to this person, and I sent a question to that address.

Adam Smith: So one day, and I believe it was around 2003, I got an email from somebody in Germany, quoting my original post some—what is it?—10 years previous, saying, you know, “Are you Adam Smith? Did you post this to the Internet?” I replied back.

Ralf Dose: Ten minutes later, I had an answer saying, “Yes, that was me. And everything you’re looking for is still sitting in my attic. I’ll send you photographs tomorrow.” I had a very sleepless night. And, actually, the funny thing was, the next day was my birthday, and I had invited some friends from the Hirschfeld Society, so I got the big birthday present just the night before.

EM Narration: Ralf Dose flies to Canada a few months later to collect the suitcase. Sitting in Adam Smith’s Toronto living room, Ralf takes several deep breaths, and with eyes as wide as a five-year-old on Christmas morning, he hesitantly flicks open the latches, and lifts the lid. Unlike a five-year-old on Christmas morning, Ralf takes his time. He carefully picks up and examines the contents of the suitcase one by one, as though he can hardly believe they’re real—papers, notebooks, letters… And a leather box. He opens it. At last, Ralf Dose comes face to face with Magnus Hirschfeld, as he holds his death mask in his hands.

The suitcase was one of several that had belonged to Li Shiu Tong. In the 48 years after Hirschfeld died, Li had carried his lover’s death mask, journals, books, papers, and last testament with him from France to Switzerland, to Hong Kong, and finally to Vancouver, Canada, where Li died in 1993. Li’s family had kept some of the books and papers, but tossed the rest. That’s how Adam Smith came across them in the suitcase when he was collecting the trash.

Today, the suitcase is in the Hirschfeld Society’s office in Berlin. After decades of painstaking work, some of Hirschfeld’s scattered belongings came home. And last May, his far-flung family—also decimated and scattered by the Nazis—came together in Berlin as well.

That’s Vivian Kanner singing at the closing of a huge celebration I attended last May at Berlin’s House of World Cultures auditorium, which is just steps away from where Magnus Hirschfeld’s institute once stood. Hirschfeld’s relatives from Australia, the U.S., and Israel were among those singing along to this popular German birthday song on what would have been Uncle Magnus’s 150th birthday.

I have to wonder what Dr. Hirschfeld would think about the current state of the movement he founded. So much of what he fought for has come to pass. But it took time. A long time. As Dagmar Herzog said to me: “Movements are made up of moments, and those moments can be spread over decades, even centuries.” Paragraph 175 wasn’t repealed until 1994, same-sex marriage only became legal in Germany in 2017. As Hirschfeld witnessed, progress is not guaranteed. The backlash can be swift and brutal. The battle for justice that Hirschfeld waged—that we are fighting now—has been fought before, and will be fought again and again. Our hard-won rights are not written in stone. But our resolve can be. Hirschfeld’s epitaph, etched into his headstone in Nice, repeats his guiding principle: “through science to justice.” Or perhaps: through radical social action, protest, organizing, and supporting communities of color, trans, and non-binary folk… to justice. Oh, and vote. That, too.

Making Gay History is a team effort. Thank you to executive producer Sara Burningham and the rest of the Making Gay History crew: producer Josh Gwynn, production coordinator Inge De Taeye, social media producer Denio Lourenco, photo editor Michael Green, and our guardian angel, Jenna Weiss-Berman. A special thank-you to our Berlin-based producer, Shane Thomas McMillan, and to Adam Smith for generously sharing with us his photos of the items in the suitcase, and the video he took of Ralf opening it, and most of all, for rescuing that piece of our history from the dumpster. You can see Adam Smith’s photos and video on our website. Our theme music, and this episode’s specially commissioned Making Gay History rag, were composed by Fritz Myers.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. Season four of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, and our listeners, including a generous gift from Andra and Irwin Press.

If you like what you’ve heard, tell your friends or give us a shout-out on social media. Find us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Tumblr. And to find out what we’re cooking up next, subscribe to our newsletter. You can find the link for that and all our previous episodes, as well as archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people we feature at makinggayhistory.com. That’s also where you’ll find a link to a reconstructed version of the silent movie Different from the Others.

So long! Until next time!

###