Leonard Matlovich

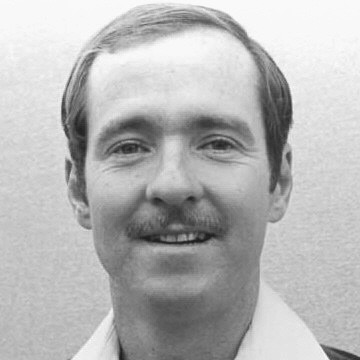

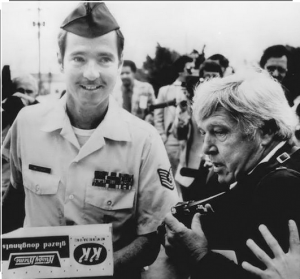

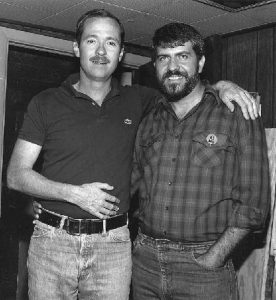

Leonard Matlovich in an undated photo. Credit: Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen, The New York Public Library.

Leonard Matlovich in an undated photo. Credit: Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen, The New York Public Library.Episode Notes

When Leonard Matlovich was thrown out of the Air Force for being gay, he sued for reinstatement. It was 1975 and it was the first case of its kind. Hear the LGBTQ rights pioneer—and startlingly frank one-time racist—in conversation with Studs Terkel.

Episode first published December 24, 2020.

———

Learn more about Leonard Matlovich on this website dedicated to his memory and in this tribute video.

Matlovich enlisted in the U.S. Air Force in 1963. After 12 years of service, he purposely outed himself, inspired and guided by gay rights pioneer Frank Kameny, who had been looking for a test court case to challenge the military’s ban on homosexuals. Learn more about Kameny in this episode from Making Gay History’s first season.

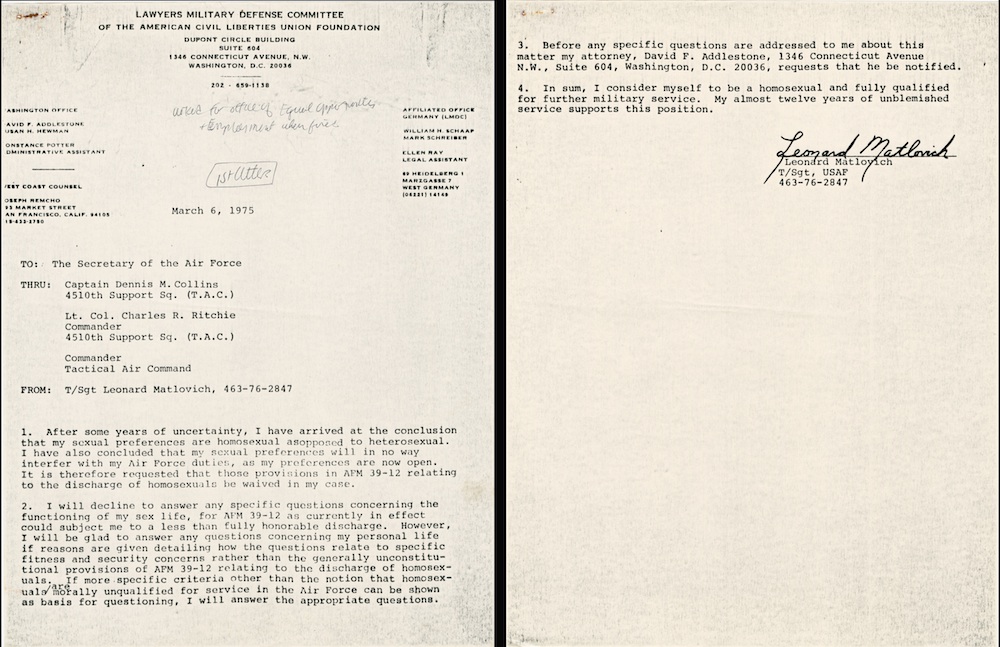

Matlovich declared his homosexuality to his commanding officer in a letter he hand-delivered on March 6, 1975; you can read it below.

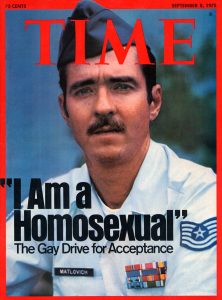

Matlovich’s case quickly garnered national attention. Read early New York Times coverage here and watch Matlovich’s first televised interview from May 26, 1975, here. On September 8, 1975, Matlovich appeared on the cover of TIME magazine with the headline, “I Am a Homosexual.” Listen to one of his friends describe seeing the issue on newsstands here. Read the original TIME article here.

Matlovich’s case inspired other enlisted gay and lesbian people to fight for their right to serve, including Navy officer Vernon E. “Copy” Berg. Listen to our episode featuring Berg here.

In 1978 Matlovich’s story was made into a film titled Sergeant Matlovich vs. the U.S. Air Force; you can see the trailer here.

For more on LGBTQ people in the military, start here. For a more in-depth look, check out Allen Bérubé’s Coming Out under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II (which was made into a documentary film) or Randy Shilts’s Conduct Unbecoming: Gays and Lesbians in the U.S. Military. A few oral histories with LGBTQ veterans are available through the Library of Congress here.

In the episode, Matlovich discusses his racist past and internalized homophobia. He expands on those themes in this 1975 interview with Ronald Gold.

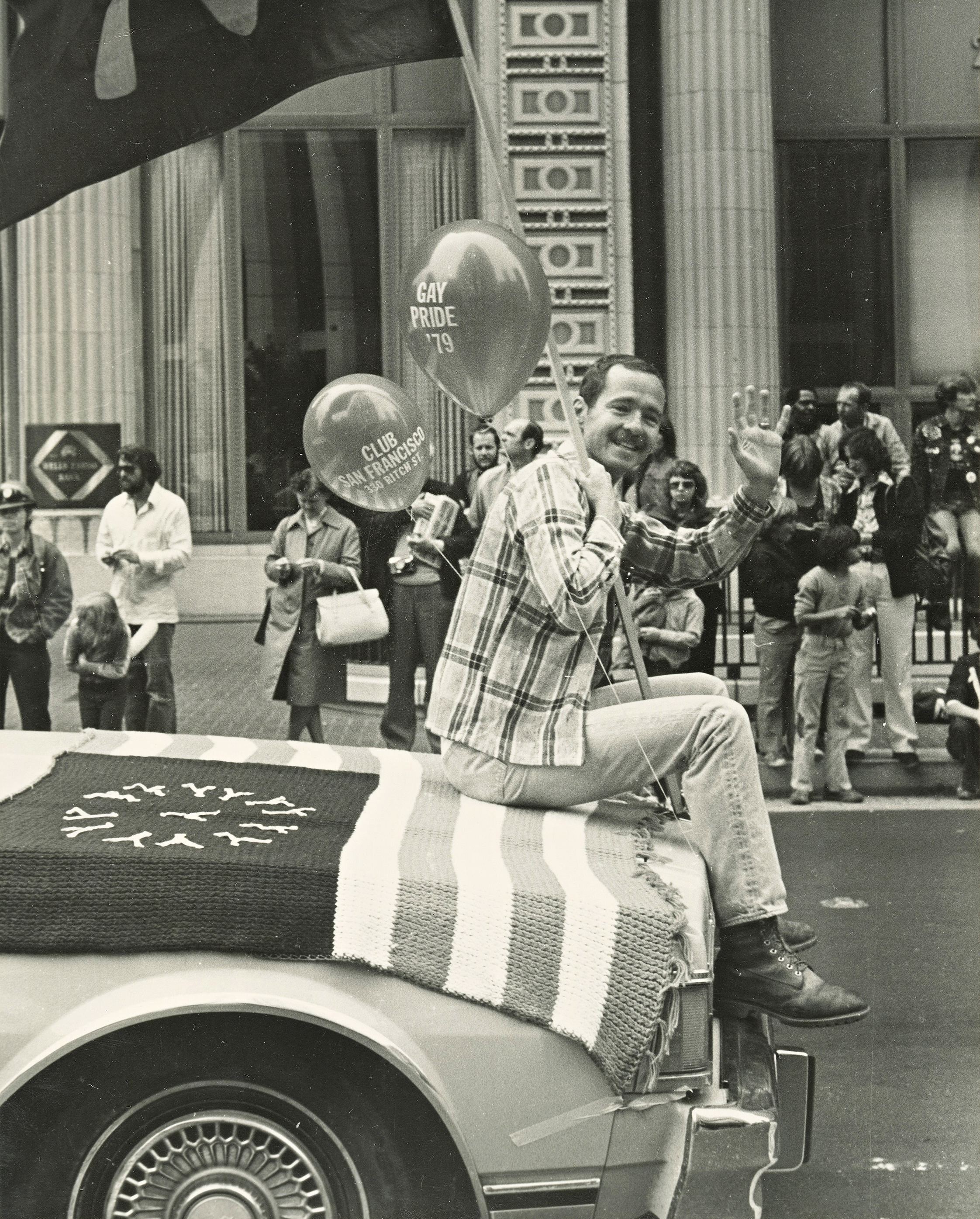

Matlovich’s LGBTQ activism did not end with his court case. He lent his voice and influence to several battles against homophobia: Anita Bryant’s anti-gay crusade; California Proposition 6, which sought to ban gay and lesbian teachers from public schools; the Reagan Administration’s indifference to the AIDS crisis; and more. He also contributed to the founding of Affirmation, an affinity group for LGBTQ Mormons, and forced Northwest Airlines to end its discriminatory policy regarding passengers with AIDS.

In this 1987 interview with Good Morning America, Matlovich disclosed that he had contracted AIDS. On May 7, 1988, he delivered his final public speech in front of the California State Capitol during the March on Sacramento for Gay and Lesbian Rights; watch an excerpt here. He died just weeks later, on June 22, from AIDS-related complications.

Michael Hippler, Matlovich’s biographer, wrote this obituary in the Bay Area Reporter as well as this article about getting to know Matlovich.

Matlovich’s tombstone at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC, identifies him not by name but as “[a] Gay Vietnam Veteran.” Frank Kameny’s cenotaph is located nearby. Read the story behind Matlovich’s headstone here.

Matlovich has been lovingly memorialized on the AIDS Quilt; see some of the many panels dedicated to him here and take a moment to search the whole quilt here. The Matlovich Society, a gay rights organization in Maine, was named in his honor.

Matlovich’s official military personnel file, which is nearly 1,000 pages long, has been digitized by the National Archives and Records Administration; you can read it here. Matlovich’s papers are preserved by the GLBT Historical Society; check out the collection guide to see what’s inside. They also have an oral history with Matlovich’s Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund attorney, E. Carrington Boggan; you can read the transcript here.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History.

In September 1975, a stunning issue of TIME magazine hit the newsstands. On the cover was the photo of a young man wearing his Air Force uniform. His name tag said “Matlovich.” And the huge headline read: “I Am a Homosexual.” I had just started my senior year at Hillcrest High School in Queens, New York. By then I knew I was gay, too, but I would have died before admitting it to anyone. And I sure wouldn’t have announced it on the cover of a magazine with millions of readers. I’d like to think I admired Leonard Matlovich for his courage. But it’s more likely that I thought he was crazy.

I never got to interview Leonard; he’d died by the time I started work on the original Making Gay History book. But Studs Terkel did, and I’m glad we get to share Leonard’s voice thanks to our work with the Studs Terkel Radio Archive.

One of the things I love about our history is how its many threads come together at different times. One of those threads was the tireless work of gay rights activist and firebrand Frank Kameny. Frank is featured in his own Making Gay History episode, but his name comes up in plenty of other episodes, too. And he played a pivotal role in Leonard’s story.

Frank had been looking for a test court case to challenge the military’s ban against gay service members. In 1975 Leonard stepped up to the plate. The 31-year-old Air Force tech sergeant declared his homosexuality to his commanding officer, and when he was discharged, he sued for reinstatement. It was the first case of its kind—and Leonard instantly became the public face of a bitter fight for equal treatment of LGBTQ service members that continues to this day.

Leonard was a picture-perfect spokesman. He had an exemplary record, was a decorated Vietnam vet, and taught classes designed to ease racial tensions in the armed forces. He was a patriot, a conservative, and a believer. He grew up Catholic, and later became an elder in the Mormon church.

But before Leonard became a champion for equality, he first had to overcome his homophobia and racism—as you’ll hear in his conversation with Studs Terkel, which was first broadcast on November 14, 1975.

Just a heads-up: Some listeners may find what Leonard says about his past racist beliefs to be shocking.

———

Studs Terkel: Your case is obviously gonna be a memorable one. Of course we’re breaking through something involving, what is more macho than the military? The Army. In this case the Air Force. And this is of course, this, you, you’re right in the heart of the heart of machismo, are you not?

Leonard Matlovich: To say the least. Yes. And they want to keep that image. And I think it’s a crazy mixed up world we live in when we’re rewarded for killing and hating, and punished for loving. And maybe that macho image, it’s a wrong image. And it tends to make people want to hate, to kill, and to murder.

ST: So we gotta go back to beginnings with Leonard Matlovich. Who are you? Where’d you come from?

LM: Well, I usually tell people that, uh, my father spent 32 years in the Air Force. So I tell people that I was born in Georgia, raised in Alaska. Joined the Air Force in England. I’m a resident of Florida, live in Virginia, and visiting Chicago today. And I say that everything that I am and everything I hope to be I owe to the United States Air Force. I was born on an Air Force base, and graduated from Air Force high school. And most of my higher education has been through the Air Force.

ST: So it’s been military all your life.

LM: Right. Even the ability to do what I’m doing today, to fight regulations that are considered unconstitutional, I have to owe that to the Air Force, too. They gave me the courage because they, they kept telling me over and over again, and I kept telling the classes I taught in human relations and race relations, that anything less than equality and justice is not tolerated in this country.

ST: You were of a different political background entirely.

LM: Oh, absolutely I was. I, um, uh, the Confederate flag I, I idolized for many years. It was a symbol of, um, I don’t know… I, I don’t have words for it, but I idolized that symbol, a symbol of the past and the way things were and they should still be. Not necessarily slavery, but the white of white—the right of white oppression. Uh, dedicated for Barry Goldwater, door to door handing out literature for him. I opposed the ’64 Civil Rights Act with fervor. Just went—

ST: And of course no questions about the Vietnam War.

LM: Oh, absolutely. I spent three tours over there just to, you know…

ST: Yeah.

LM: … fight my country—or fight the war for my country and for equality. It’s strange, I went to Vietnam to fight for a yellow man’s equality, and I hated Blacks in this country.

ST: And so we come to how changes occurred in the way you look at the world, okay? So you’re part of the Air Force. It’s your life. In fact, even now you want to go back. How did it come about? Now, perhaps reflect now your own thoughts and experiences to what happened yourself.

LM: I think, as a child growing up, I thought to be gay it meant that I had to wear a woman’s dress, I had to molest little children, and I had to go in bathrooms and watch people. And I never wanted to do these things so…

ST: This was the myth to which you subscribed.

LM: Right. Which I thought about being myself. So because I kept, because I knew I was gay, yet I didn’t want to be that way, there was this internal conflict, and I had a low self-image of myself. So if I could have someone who was lower than I was, the Black American… I even for a while hated Jewish Amer—not Americans, but Jewish people in general. And I didn’t meet a Jew until, um, June of this year, to the best of my knowledge. I’m sure I had. But as long as I could put someone else down, then I wasn’t the lowest person on the totem pole. So I spent most of my life putting others down.

I think, uh, Jesus said that you shall know the truth and the truth shall set you free. And I believe that truth is who you are and what you are. And once you know those things, you are set free. And once you can accept who you are and what you are, then you can love others. You can’t love others until you love yourself, and as long as you hate yourself you’re gonna hate others.

ST: And so all these years as a kid, or whenever you discovered you were gay, as, uh, you were afraid because of the sense of shame that would be imposed and the myths to which you subscribed. Somebody told you…

LM: Right.

ST: Whatever, whoever, or the society—

LM: Well, Hollywood itself…

ST: Hollywood.

LM: … and the movies. You’d see things in the movies, or sensationalism in radio or the press or, or, um, TV, whenever a gay murder or something like that, they played it up big. And, “Homosexual murder!” “Homosexual slaying!” They went in details. And, and as a child growing up, this is the only type of role model I had. Up until about the age of 29, I had never met another gay person in my life either.

ST: Oh, so there was a sense of loneliness here, too.

LM: Oh, absolutely. It’s strange, I’d use the word queer and faggot and put gays down.

ST: You did? You did?

LM: Oh, absolutely.

ST: Yeah.

LM: Trying to convince those around me—I had such a guilt complex being that way, trying to convince others around me that I was not that way. “See, I put them down, so I can’t be that way.”

I remember the first person I told that I was gay, the first straight person, he was my roommate. And I thought—this was about 29, I was 29 years of age. And I had to tell someone. And about five minutes later after I told him, he moved out and told me that, uh, “If you see me on the streets, you can say ‘hi’ to me, but don’t you ever come around where I live. I want nothing to do with you.”

ST: That’s funny.

LM: So, uh, I still had a low self-image. And when someone who I thought was my friend, if this is the way they reacted to me being gay, then I thought, well, will everyone react that way to me, and everyone reject me, and have nothing to do with me?

ST: What interests me is also this question, the myth of, uh, a homosexual not being a good soldier.

LM: I think gays who are in the closet have to go around proving their manhood. And to prove that, hey, I’m not the stereotype gay.

ST: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

LM: I, I’m really a man. And they go around to extremes to prove their manhood.

ST: But proving their manhood in this ersatz macho way.

LM: Right, exactly.

ST: Hitting somebody or…

LM: Right.

ST: … or saying, “By god, ours is the greatest country in the world, and we’ll put anybody down.”

LM: That’s right.

ST: Or as you did as a young kid putting down…

LM: Blacks.

ST: … those below you.

LM: Right. Sure.

ST: Now, when did the aware—’cause you’re a different person now, and you’re out. Like, when did these changes occur?

LM: Oh, it was a very, very slow process.

ST: Yeah.

LM: Very slow process. One of my very first supervisors was a Black individual. And when I first met him, others—he was an enlisted man. First of all, that was a couple strikes against him in my own mind, that he was enlisted and Black.

ST: Mm-hmm.

LM: Although I was enlisted also.

ST: Mm-hmm.

LM: That they told me he had a business law degree, a doctorate in business law. And I kinda laughed at it and said, “Oh, come on now, a Black individual? No way.”

ST: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

LM: Stereotype Black. They probably gave him that education. You know, free diploma just for their quota system. And as one stereotype after another began to collapse, as he used words, uh, nickel—not nickel-and-dime words, 50-cent words—and he really knew what the meaning of ’em was. And I was amazed. And then he invited me over to his house to meet his wife and kids for dinner. And I had all the stereotypes of his house. It’d be dirty and the dishes would be piled up in the sink and have a terrible odor, and the furniture would be cut and tore up. And I was really afraid to go there. And when I walked in the house, I was amazed. It was spotless. I would’ve eaten off the kitchen floor.

And this was one individual that had helped me with one stereotype to collapse after another. And I began to… First, well, first of all, I said about him, “Well, he’s different, he’s not like the rest.” And then I met another Black who was different, not like the rest, and then another one who was different, not like the rest. Until I began to look around and see so many different individuals. And just the more I met, the, the more the stereotypes collapsed.

And as I learned more and more about Black Americans, that at one time in this country, they were so ashamed of being Black, the color of their skin, that they used to use bleaching cream on their skins, and they tried to straighten their hair. And I related that to myself, that I tried to—although I was gay, I tried to lead a, a heterosexual life, dating women. I went to extremes to prove that I was straight and not gay.

ST: This matter of relating to somebody seemingly unrelated to you, and that click, isn’t it?

LM: Right. Exactly.

ST: You know, James Baldwin speaks of that as a moment of liberation. Because he thought he was alone in the world till when he picked up a novel of Dostoevsky, and he read something, and he goes, “My god, that’s my condition.”

LM: Exactly.

ST: And that moment [inaudible] was a liberating moment.

LM: The debt I owe to Black Americans, and probably the debt that America owes to Black Americans, probably will never be repaid. Because they have shown us that through, uh, perseverance and, uh, determination, the laws can be changed, and attitudes can be changed.

ST: In, during your hearing, some of the witnesses on your behalf, who were they?

LM: Well, out of the 20-some witnesses that came on my behalf, there were three white witnesses and about 19 Black. And it seemed—to me, it was a little shameful to me that, I remember back in my white racist days, that the very individuals who I put down came to my aid when I needed it the most. I guess people can forgive and forget, and people can change. There’s, uh… You’re never too old to change and to become enlightened and to change.

ST: The point you’re making now about the capacity, the capacity to change, that’s what your story is really about.

LM: It’s a human capacity.

ST: Yeah.

ST: Talking about the right to…

LM: The right to be.

ST: … be.

LM: My philosophy now is that everyone in the world should be allowed to do what they want, when they want, where they want to do it, as long as what they’re doing does not violate the rights of another human being.

ST: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: What two consenting adults do in their bedroom is their business and no one else’s. And for someone to put them down or… Just that two men can touch and love and have feelings of to want and be wanted and to need and be needed and to desire and be desired and just to love and be loved, I think is very, very beautiful. And that parents growing up today will give our little children guns, and we are very proud of them when they play Cowboys and Indians and run around. But when they show emotions and, and love, and two little boys touch, people get uptight, and they’re so afraid that their child may, may love. It’s very sad.

ST: Isn’t it the equation of tenderness and love with sissiness?

LM: Unfortunately, you’re right.

ST: Or, or, or homosexuality?

LM: But it, but to love…

ST: Yeah.

LM: … can be very, very masculine, and it can be very, very feminine. It has nothing to do with sissy or, or what have you.

ST: Yeah, yeah. You know, I was thinking, you said, uh, you wanted your parents to be proud of you.

LM: I think probably parents are gays’ biggest hang-up—not that it’s a hang-up, but they seem to love their parents very, very much, and they want their parents to be very proud of them. Therefore, they deprive themselves of a life to make their parents proud. I have a 41-year-old, 41-year-old man who calls now who’s waiting for his mother—who I think she’s 77—he’s waiting for her to die before he comes out of the closet, before he has any sexual contact at all with anybody. And he says, “Well, soon as my mother dies, I’ll come out. And I’ll…” That’s so very, very sad.

ST: Yeah, yeah.

LM: And it got to a point where I finally gave my parents an ultimatum. I said, “Either you’re with me or against me. But for 30 years, I lived to make you very, very proud of me. And now I have to live for my own self. I have to live my own life. I have to be Leonard Matlovich and not your son Leonard Matlovich.”

ST: So I suppose I have to ask this question. Your father, in the Air Force all these years, uh… Your case is cause célèbre. What, what is your paren—what are your parents’ feelings toward you now, about the case?

LM: Well, very, very positive. Uh, seemed like all my fears and all my expectations were just that, fears and expectations. That, um—my mother took it, I think, harder than my father did. Last time I talked to my father, he said, “My son the celebrity, when are you coming home?”

ST: [Laughs.]

LM: So, uh, it’s strange how I thought he, being the very conservative member of the family, that, uh, he would take it the hardest. But he cried when he first heard about it. It’s, it’s hard to have a child that’s gay in America today because they are so discriminated against. And if my last name were Jones or Smith, it would be easier, too, for my parents. But with a name like Matlovich it’s harder, and they’re more identifiable. And it, it’s rough.

ST: By the way, have you, have you heard from older gay people? A great many, I, I imagine were very status quo-conscious.

LM: Oh, absolutely.

ST: Quiet and conservative, reactionary, too, so that attention might not be drawn to them because of the fears. Isn’t that so?

LM: Oh, absolutely. The day I drove up to Washington, DC, to pick up the paperwork to [inaudible] the head of the Air Force, a gay friend of mine went along with me and pleaded with me all the way up and all the way back, “Don’t do it. Please don’t do it.” Uh, you know, “What are you doing? Leave things alone.”

ST: Yeah.

LM: “They don’t know you’re gay. Don’t rock the boat.”

ST: Yeah.

LM: I had a lot of opposition from my gay friends when I first started this venture.

ST: Yeah. Is there less now?

LM: Oh, absolutely.

ST: Yeah. By the way, you spoke of you being Catholic. You were a conservative Catholic. I suppose then, I suppose, sense of sin…

LM: Oh, I can remember whenever I’d, uh, commit masturbation or anything like that, if I, if I fell down I’d blame it on that. Or if I, [laughter in background from unidentified person in the studio] if I failed a test, I’d blame it on that for doing that because God was punishing me…

ST: Yeah.

LM: … because I did something wrong. Those were b—those, as I look back on those days as an adult, what a waste of, uh… Just, what a waste.

ST: Think of all the pressures—religion, that is organized religion, uh, the military, school, society, everything—and that’s quite a burden to carry, isn’t it?

LM: It was. It was getting to the point where I had to make a decision. Either I had to come out or… I just didn’t know what I had to do, but I had to do something. I just couldn’t continue living this very, very lonely life. Uh, stayed in that closet for so many years to make my parents so very, very proud of me. And because I love the Air Force very much, and I love my job and I knew I’d lose it, so I deprived myself of, um, any type of sexual or even emotional or contact at all. And that in itself may dispel the stereotype that gays are very promiscuous, because for 30 years I went without. I didn’t even kiss another person or hold another person for 30 years.

I’m still having troubles today relating to people, because for 30 years, depriving myself of so much, and putting yourself in such a, a track…

ST: Yeah.

LM: … a way of life that it’s difficult to begin to express and to love and to feel.

ST: Yeah. You use the word, you were in the closet—see, again the hiding, isn’t it?

LM: Right.

ST: Subversive. Something subversive—

LM: Well, you feel like… Oh, it is. It’s very…

ST: Yeah.

LM: … it’s very cloak-and-dagger-like.

ST: Yeah.

LM: You feel like a foreigner in your own country. Believe it or not, I still have a lot of uptightness and hang-ups. Uh, I was riding on a train from New York City to Connecticut. There were—this was about 2:00 in the morning. And there was, uh, five of us in this car. And the individual with me, he wanted to lay his head on my shoulder, and I wouldn’t let him do it. I said, “No, uh, just not gonna let you do it.” He said, “Well, now, you hypocrite, you.” He said, “Every person in this country, you know, 52 million people, or 200 million people, know that you’re, you’re gay, and you won’t let me lay my head on your shoulder.” And I said to him, “Well, right now if I did it I’d only be doing it for one reason, and that would be to upset the other people in this car. And I’m not out to upset anyone.”

ST: Yeah. Isn’t that something, the fear, you’ll fear that they will be up—of course, your feelings about them, your own hang-up of course still there… But also—

LM: Oh, it’s gonna take time.

ST: Yeah, but also the fact that…

LM: Thirty years of brainwashing.

ST: … they would be up—now, why should they be…? We come to it. It’s that terrible fear that a society imposes, that it’s wrong to be this, even though you are naturally that, therefore you have to be what I am. Oh, one last question. How’s the case now? There’s an appeal.

LM: Right.

ST: You’ve been discharged, but your lawyers, you are appealing it.

LM: Judge Gerhard Gesell, the federal court in Washington, DC, has ordered the Air Force back into court the first week of January to justify their regulations under constitutional grounds. And we feel very optimistic here that we may win at this court level.

ST: By the way, do you, do you still want to be in the Air Force?

LM: At this point I do. There’s no question about it.

ST: Mm-hmm.

LM: We don’t know how long it’s gonna take to get into the federal courts, or to get to the higher courts, or what the schedule’s going to be. But if it takes that long, I may be an entirely different person by then. But right now, yes, I would like to be back in the Air Force.

ST: And we’re talking about changes, aren’t we?

LM: Exactly.

ST: That it’s possible for anybody to change his outlook on life.

LM: Well, I’m not the same person today I was yesterday. And just by being here talking with you I’m a different person. And my span of influence, or span of people I’ve met, is much broader now than it would have ever been.

ST: So you’re freer.

LM: Exactly. I walk a little taller and a little prouder each time I, I meet a new person, because—

ST: That’s our subject. Liberation. Leonard Matlovich, my guest, thank you very much.

LM: My pleasure.

———

EM Narration: Leonard Matlovich’s case bounced around the courts for several years. In 1980, U.S. District Court Judge Gerhard Gesell ordered Leonard’s reinstatement. When the Air Force offered a settlement instead, Leonard accepted. By then he’d also been excommunicated from the Mormon church. In the years that followed, he continued his work as a gay rights advocate, speaking out against homophobia and, later, the government’s indifference to the AIDS epidemic.

Leonard Matlovich died from AIDS-related complications on June 22, 1988. He was 44. Before his death, he designed his own tombstone at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC, to serve as a memorial to all gay veterans. So he left off his name and identified himself simply as “[a] Gay Vietnam Veteran.” Inscribed underneath is a quote. It reads, “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.”

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: senior producer Nahanni Rous, co-producer and deputy director Inge De Taeye, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman and our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Studios, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season eight of this podcast is produced in association with the Studs Terkel Radio Archive, which is managed by WFMT in partnership with the Chicago History Museum. A very special thank-you to Allison Schein Holmes, Director of Media Archives at WTTW/Chicago PBS and WFMT Chicago, for giving us access to Studs Terkel’s treasure trove of interviews. You can find many of them at studsterkel.wfmt.com.

This podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, proud Chicagoans Barbara Levy Kipper and Irwin and Andra Press, and our listeners, including Patrick Hinds and Bill Kux. Thanks, Patrick! Thanks, Bill!

So long. Until next time.

###