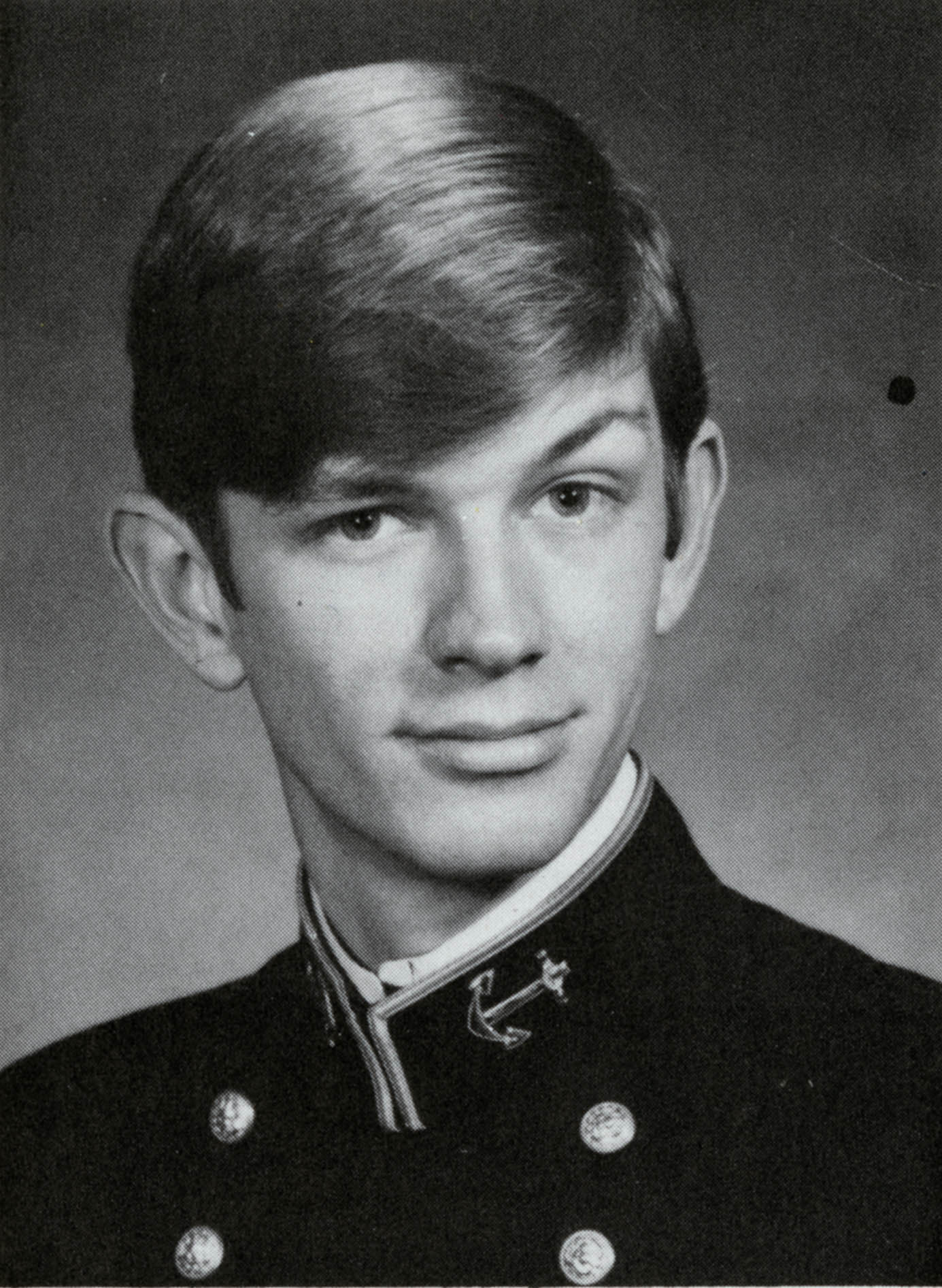

Vernon E. “Copy” Berg III

Ensign Vernon E. “Copy” Berg III, 1975. Credit: Photo by the U.S. Navy.

Ensign Vernon E. “Copy” Berg III, 1975. Credit: Photo by the U.S. Navy.Episode Notes

In 1975, long before “don’t ask, don’t tell,” the Navy asked, and Officer Copy Berg told: “Yes, I am gay.” When Copy chose to challenge the military’s ban on homosexuals, the Pentagon fought back with all guns blazing.

Episode first published November 7, 2019.

———

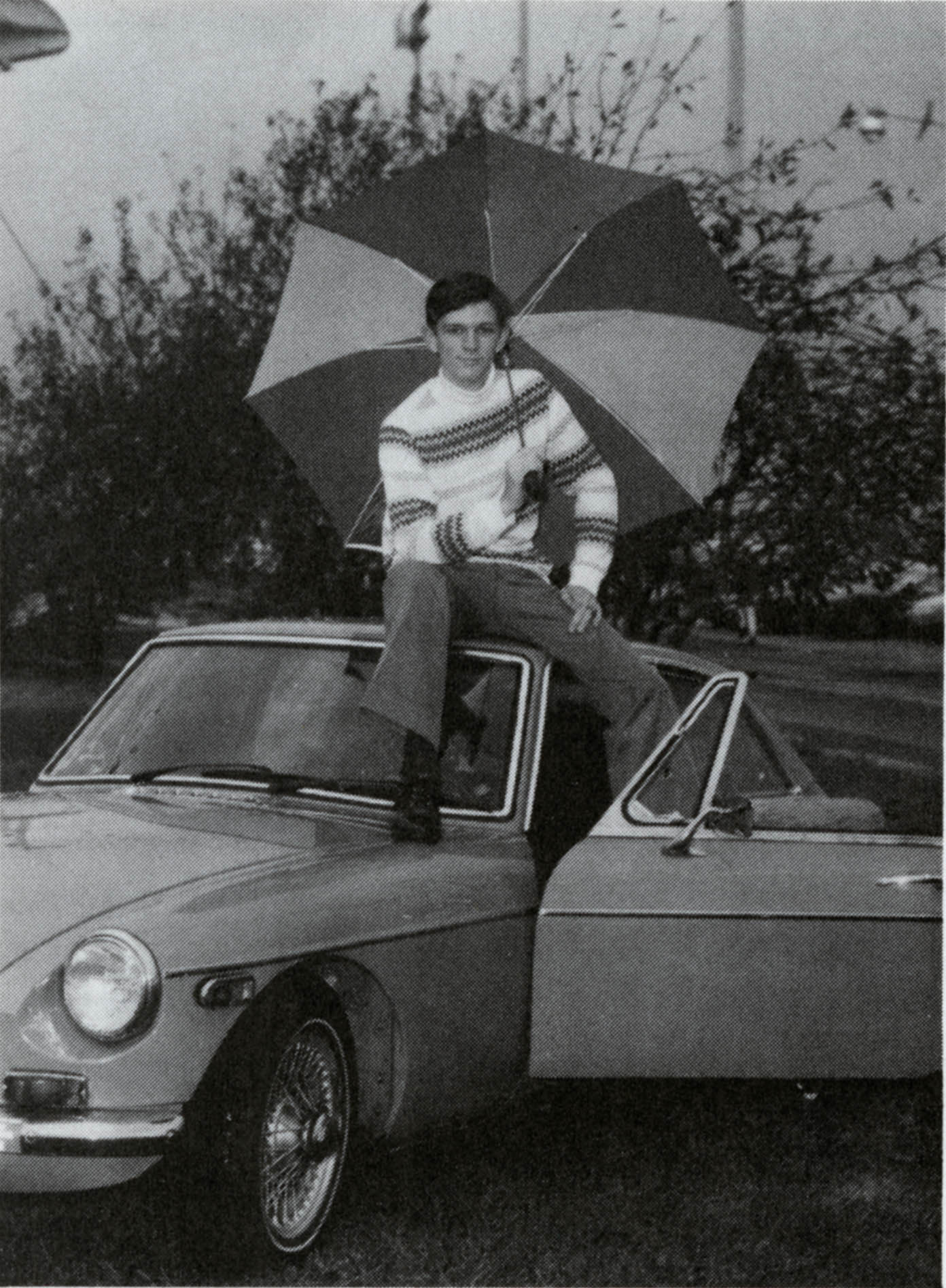

From Eric Marcus: “I was thoroughly charmed by Copy.” That’s what I wrote, a bit primly, in my 1989 post-interview notes about Vernon E. “Copy” Berg III. Copy was cool, smart, and very attractive. Sitting on the floor of his artist’s loft, warmed by a wood stove (in Manhattan!) and sipping tea on a winter afternoon, I’m sure I had to remind myself more than a few times that we weren’t on a first date. I was there as a journalist to interview Copy about his role as a young Naval officer who had challenged the military’s long-standing ban against homosexuals.

Like many of the people I interviewed, Copy didn’t set out to be a gay rights pioneer. But when he had the chance to fight the military over his discharge, he chose a path that moved the needle in the direction of justice and helped lay the groundwork for the right of LGBTQ people to serve openly in the U.S. military.

By the time I met Copy, he was 38 and had built a career as an artist. His military service and high-profile court challenge were well behind him, but his memories remained fresh. Join me in Copy’s cozy Soho studio and have a listen.

———

To learn more about Copy Berg, read his 1999 New York Times obituary here. The Times first reported on Copy’s case in this March 1976 article.

The less-than-honorable discharge Copy received from the military after his administrative hearing was upgraded to honorable in 1977. The following year, the D.C. Court of Appeals ruled that the Pentagon could not discharge homosexuals from the military without offering specific reasons in addition to their homosexuality; read Copy’s appeal here and the judge’s decision here. (Thousands of additional documents pertaining to Copy’s case can be found among his records in the Manuscripts and Archives Division of The New York Public Library.)

While Copy’s case was unfolding, President Jimmy Carter’s administration had been putting pressure on the Pentagon to change its policy against homosexuals. Midge Costanza, a top aide to President Carter, was instrumental in the effort; for more on Midge, listen to our episode with her then-partner Jean O’Leary here.

In 1981, the Department of Defense reaffirmed its ban on gay men and women serving in the military, but it amended its policy to state that those forced out solely for reasons of homosexuality would receive an honorable discharge. The change applied retroactively as well so that any person who had been discharged for homosexuality could apply to have their discharge upgraded. Read Copy’s reflections on the qualified victory in this 1981 Philadelphia Gay News interview.

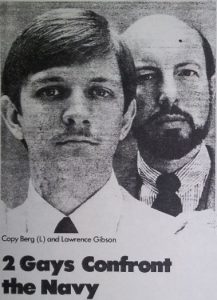

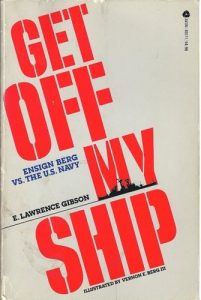

Lawrence Gibson, Copy’s civilian boyfriend during his time in Italy, chronicled Copy’s case in Get Off My Ship: Ensign Berg vs. the U.S. Navy (illustrations by Copy). In 1979, Lawrence and Copy were interviewed together by Enlisted Times and WBAI (interview starts at 5:02).

In the episode, Copy references Senator Joseph McCarthy’s persecution of homosexuals, a time known as the Lavender Scare (concurrent with the better-known Red Scare). For a short history of the era, read this National Archives article. For a more complete account, read David K. Johnson’s The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government, which was recently made into a documentary.

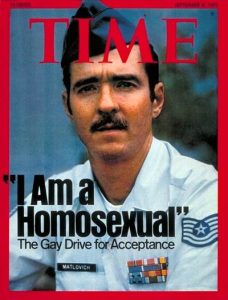

The episode also mentions Air Force Tech Sergeant Leonard Matlovich (featured in this MGH episode) and his lawsuit challenging the military’s ban on homosexuals. Read more about Leonard here and here.

For more information on LGBTQ folk in the military, start here. For a more in-depth look, check out Allen Bérubé’s Coming Out under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II (which was also made into a documentary film) or Randy Shilts’s Conduct Unbecoming: Gays and Lesbians in the U.S. Military. The Library of Congress has a few oral histories with LGBTQ veterans here.

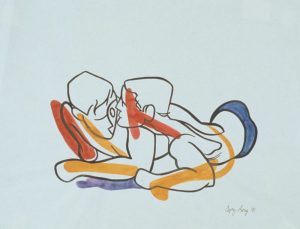

After his career in the Navy ended, Copy became an artist. His later work was deeply influenced by his HIV diagnosis; see some of his art here.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History!

It’s been 30 years since I started interviewing LGBTQ trailblazers and allies for my Making Gay History book. Not everyone I spoke with left a lasting impression. Some of the people I met with faded from memory and didn’t come back to life until I listened to the old recordings. Not so Copy Berg. In my post-interview notes I wrote, “I was thoroughly charmed by Copy.” Actually, I was smitten. I vividly remember sitting across from the handsome former Navy man on a December afternoon in his artist’s loft in New York City’s Soho neighborhood. We were warmed by what must have been one of the few remaining wood-burning stoves in Manhattan.

Copy was no stranger to being interviewed. In the mid-1970s, he’d been the subject of fierce media scrutiny. That’s because he was one of the first people to publicly challenge the military’s ban on allowing homosexuals to serve.

Copy was born Vernon E. Berg III in 1951. He got his nickname because he was so much like his father, Navy Chaplain Vernon Berg Jr. Copy was the oldest of four, a clean-cut kid, Boy Scout, student body president of his high school, member of the Optimist Club and the Junior Chamber of Commerce. He attended the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, where he sang in the choir and the glee club.

He was also gay. In the summer of 1975, the Navy Investigative Service confronted Copy about his sexual orientation. Copy admitted to having had homosexual relationships and offered to resign. But, as you’ll hear, that was just the beginning of the story.

I asked Copy whether he had a sense when he was growing up that he was different.

———

Copy Berg: In hindsight, I now know that I had a lover when I was in high school. At the time he was just my best friend and we were in Boy Scouts together and we did things at school together and we went everywhere together. But that meant sharing a sleeping bag and having sex.

And at the time my impression of homosexuals was they were somebody who wanted to be a woman. A cross-dresser. And so I knew that we were having sex, but to me it was just play. I knew you didn’t talk about it. But you didn’t talk about sex at all. So David and I had sex. Lots of it, for almost four years.

But at the same time, I was still dating women. I mean, David and I would double-date with women and drop the girls off and go home and have sex. And so that continued all the way through high school until my senior year and I got mononucleosis, which knocked me out of school for six months. And it sort of ended the relationship with David, because by the time I came back to school I was very focused on graduating and getting to Annapolis and to do that I had to go off to military boot camp.

Eric Marcus: That was what year then that you were in…?

CB: I graduated from high school in 1969 and then went to boot camp in ’69, June of ’69. While men were walking on the moon, I was in boot camp.

EM: These were pretty hot political times.

CB: Oh, yeah, there was foment everywhere.

EM: Were you aware of what was going on?

CB: Well, yes and no. I mean, I was living in a military environment. All my friends were military juniors. Their parents were career military people and I went off to Annapolis. And, yes, we read about peace demonstrations in the newspaper and, yes, you read about drugs in the newspaper, but they were all still considered fringe.

Those were the days when we still believed that Richard Nixon was a great guy and he hadn’t done anything wrong. There was no sense that the government was against us the way we know now it was. So you could still tell yourself that all was right in the White House and that these fringe groups were wrong.

EM: Were you aware that there were gay rights groups that were part of the fringe or that was beyond—

CB: No, that was beyond my experience. My initial experiences were mostly the military versus the peace demonstrators. When I was at the Academy, we were told—which is completely against policy—that we were not allowed to wear the uniforms off base. In normal times, like now, you always appear in uniform whenever you’re traveling in military functions, or going someplace, or even traveling overseas to duty assignments. Well, those days they didn’t even allow us to go off the base in uniform because we were subject to violence. And, um, …

EM: At the hands of whom?

CB: Of demonstrators, to use a broad general title. Vietnam was very unpopular and if you walked down the streets in uniform you were subject to abuse.

Having been through that experience, I then graduated from Annapolis and my first duty assignment was in Italy. I was with the NATO forces. And I was an assistant chief of staff to Vice Admiral Turner on the Sixth Fleet staff, for public relations.

EM: What officer level were you?

CB: I was an ensign at the time. I had just graduated. I had spent a year in the fleet. And, um, and that’s when things broke.

EM: How did it all break? You didn’t plan on this happening.

CB: No, no. I didn’t plan on it. And that’s a distinction I make frequently, is I didn’t start this. People accuse me of being disruptive. None of us start these things. Somebody else does. But once provoked, I responded.

EM: How did it happen? How did they…?

CB: We don’t…

EM: What were the circumstances when you were discovered?

CB: Right. When I was in Italy, I was called in by the Naval Investigative Service officer on board the ship.

EM: What was the date?

CB: It’s like June of 1975. June or July. And I didn’t think anything of it because this guy was a friend of mine. I had worked on other cases with him involving other people and I thought he wanted to talk to me about one of my men. And they said, “We’re here to talk about your homosexuality.” I said, “What homosexuality?” They said, “Mr. Berg, we’re not naive. There’s nothing you can say that will surprise us.” And they proceeded with what I call the “good guy, bad guy” scenario. Good cop, bad cop. One guy screams at you and then he leaves the room and the guy says, “He’s in a bad mood. If you’ll cooperate, things will get better.”

There was actually another person involved at the time. There was a civilian teaching English on board the ship. And they had him in another room. And Lawrence and I did have a relationship. And they would go from room to room and say, “Mr. Gibson has just said this, do you deny it?” And then they would take what I said and go back to him and say, “Mr. Berg has just said this, do you deny it?” So, essentially, the short form is, I gave ’em a confession. I said that yes, I was gay, and I had had sex with these people on these occasions.

I guess I never answered the original question and that is why did all of it start? I ended up on a list somehow, I don’t know really how. The Naval Investigative Service maintains that they had a confidential informant.

EM: What he had found out was that you were in a relationship with another man?

CB: No, they didn’t know that, actually. I went in thinking that I was guilty of that. But it turned out that they had my name on a list with many other names of people at the Naval Academy. So it seems that the investigation somehow had started at Annapolis because the list that they had when they confronted me was professors and students and officers at Annapolis, most of whom I didn’t know.

They wanted to believe that I knew these people and that I was guilty of colluding with them. They still believe that all of us know each other and that there’s this wonderful underground network and we all talk to each other and we all fuck. And I was mortified. I had never been confronted by that kind of tactic. I mean, now I can tell you a great deal about it because it’s so thoroughly predictable. But at the time I was pretty buffaloed by it.

EM: Predictable in what sense?

CB: All the investigations take on the same characteristics and they always produce the same rationale and the same results.

EM: Homosexual conspiracy theory.

CB: Right. And the homosexual as enemy theory. McCarthy started the whole thing when he said that there were homosexuals in the State Department. And then he said there were homosexuals in the Army. And the whole federal establishment was put on the alert to find homosexuals and ferret them out. And prosecute them.

Because at the time of McCarthy you could say a homosexual was a communist and equate the two and everybody believed it. And I think people fail to make the connection with McCarthy. I mean, most other things have been discredited out of that period. But this attitude that the homosexual is an enemy has been maintained.

At any rate, the list had names of people that I’d heard of, but I was so upset by the implication that I had had sex with all these people, I decided the only way to establish a credibility, in other words, to be able to deny what was not true, was to assert what was.

EM: Which was?

CB: So I told them, “Yes, I’m gay and I’ve had sex with these people,” um, and then denied the rest of it.

EM: What were you thinking about your relationship with another man, given that you were in the military and knowing what the military’s views on this were? Or did you not think about it?

CB: Um, I guess I handled it the same way I handled my relationship in high school. And that was that it wasn’t something you talked about. We were very highly closeted. But it wasn’t something I was ashamed of. It was something I enjoyed and I was happy in.

I did know that if you got caught you got thrown out of the Navy. That much I knew. And there were people thrown off the ship while I was there for being gay, who had been caught in the act on the ship, which is almost always what happens. They catch two guys doing it on the ship and then they’re sent off into great disgrace, and, really, with great drama, high drama and fanfare. These people are kind of drummed off the side of the ship so that everybody knows it. There’s… They may be confidential in how they handle the records, but they’re not the least bit confidential about how they put somebody over the side of a ship and send them home.

They make it very visible and they use it as a very punitive thing. Because a commanding officer could use it to punish people. And you, it didn’t even have to be true for them to punish you and get rid of you.

Now one of the greatest ironies of the whole case and one that came back to haunt them in the U.S. Court of Appeals level, was that when I had been confronted and when I resigned, I asked to be taken off the ship to avoid embarrassment to the command. I was thinking only of the admiral, right? Well, the command denied the request. They said, “No, you can’t leave the ship. You must stay here and work.” And the reason was that my immediate superior, the commander who was over me, was due for vacation and he wanted his two weeks. So he left the ship and I assumed full responsibility for my department for the first time ever and so even the court, even the judge, could look at the record and say, “If he was a threat, if he was not competent, if he wasn’t doing his job, why did you promote him to this position that he had never held before after he’d resigned?” And it’s indefensible.

EM: So they didn’t let you resign?

CB: I submitted a letter of resignation, which they accepted, and they were sending me back for processing. They don’t actually discharge you on a ship, you have to come back to the United States to a processing center where you are then processed for discharge.

We left and came back here and I reported to Norfolk. But then I was subjected to very blatant surveillance. They followed me around. They parked a van right outside my window. I mean, it was, it was not at all like the movies. I mean, you knew the guy was there. You knew the phone was tapped.

I don’t know what they expected they could get on me because I had already said that I was gay and you would think that would be enough, they could just discharge me that way.

EM: How did this wind up going to… Why did you wind up pursuing a trial case? How did you go from resigning—

CB: Well, when I got back here and spent six months sitting there and nothing happened, um, I knew something was wrong and that it wasn’t… things weren’t going the way they were supposed to. What I didn’t know was that Matlovich had already filed suit. And because Matlovich had filed suit, the Pentagon was terrified.

———

EM Narration: Sorry to interrupt, but some background here. While Copy waited—without pay—for his discharge to be processed, an Air Force Sergeant named Leonard Matlovich had been thrown out for being gay and sued for reinstatement. Since World War II, tens of thousands of gay men and women had been discharged from the military, but this was the first law suit of its kind—an open challenge of the military’s ban on homosexuals. When Copy heard about the case, he met with Matlovich’s lawyer, and with civil rights lawyers from the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund and the ACLU and decided to mount a challenge of his own: he withdrew his resignation and decided to fight for his career. The case drew national attention and Copy’s administrative separation hearing turned into a media circus.

———

CB: The whole thing blew up. There was a whole press pool. They put up a press room. They printed parking tickets for the cars that were gonna come. They had a battery of some five attorneys against me. Representatives from the Pentagon came and sat through all the hearings, um…

EM: You were the first person in the Navy ever to say—

CB: Right. And the fact that I was an Annapolis graduate loaded the whole thing incredibly. Yeah. And the over-response was overwhelming. And, um…

EM: You were a young man.

CB: Very young. I was 23 or 24, I guess, when it was over. And so I wasn’t quite used to all that. But what, what did come easily were the press interviews. So I gave lots of interviews. And I came to realize that there wasn’t anything that I wasn’t willing to discuss. I would stand up and discuss my sexual history and the ethics of it and the religious aspects of it, because my father was a minister.

EM: He testified.

CB: He came down to the trial because I said I wanted him there.

EM: He knew you were homosexual.

CB: No. They didn’t know anything about that until the trial started, really. And I had been dating women and had almost gotten married.

EM: During this time?

CB: Well, while I was in Annapolis, so they didn’t think anything was unusual or anything was wrong.

EM: Were you frightened to tell them what was going on?

CB: Yeah, I was. It was not easy. I would never have told my parents about my sexuality had I not had to tell them. Time magazine was there, for— You know. That was what was about to happen.

EM: Why wouldn’t you have told them?

CB: I don’t know. I assume I still considered it something… It would have been a great disappointment to them and it was not something to be proud of. My father and I had been very, very close when I was a young child. I was born while he was in college and I traveled with him when he was in seminary. I used to travel with him to churches when he went to give sermons. And his first churches, I was there kind of helping him run the church from the age of two.

EM: You were his first-born.

CB: First-born. Right. I have two brothers and a sister. All younger.

EM: Eldest son, Annapolis, he must have been very proud of you.

CB: Right, um… At any rate, my father flew down for the trial because I said I wanted him there and I wanted him there in uniform.

EM: He was in the military.

CB: Oh yeah, he was still in the military. Navy chaplain. And he was a commander at the time. He had just come back from Vietnam. And a little corollary to that, he’d also been sprayed by Agent Orange and got cancer and died, um, four years later.

EM: Four years after the trial.

CB: Right. But we didn’t know all that then.

He sat back for the whole two weeks, and just watched what was going on. And listened to the interviews and he listened to all the conversations with the lawyers. And some of it was not pleasant.

EM: How do you mean?

CB: The Navy lawyer, as soon as he was appointed, apprised me of the fact that he was deeply religious and that because I was an unrepentant sinner he didn’t think he could fairly represent me. So that many of the discussions we had were over that. So finally I told him I wanted him to stay because I felt—it was sort of odd—I felt like if I could convince him, I could convince anybody. He, like my father, sort of sat there and watched what happened over the next two weeks and none of them could believe it, it was so bizarre.

EM: How was it bizarre?

CB: Well, there were, there were sort of different levels to it. One was the media level. One was the trial itself, which was supposed to be an administrative hearing but had blown up into a trial with a prosecutor and them grilling me on the stand and lots of testimony. And then the other was kind of the rumor mill. I had one commanding officer who is reported to have said that I should have my ring finger cut off because I was still wearing my Annapolis ring. There were also death threats. The Ku Klux Klan was involved. I had teenagers throw things at me out of cars. I had people scream at me on the streets.

EM: What’d they scream at you?

CB: “Get lost faggot,” you know, that sort of thing. I came out one morning and somebody had messed with the hood of my car. I came out one morning and somebody had stolen the wheels off my car.

The problem I had when my case first started, was that most of the gay activists were also peace activists. And they were anti-war activists. And the groups overlapped. I was not treated well.

EM: By whom?

CB: By most of the gay activists that I came into contact with because most of them felt that I had no business having been in the military to begin with.

EM: You shouldn’t be in the military because the military is bad?

CB: Right. That was their position. And, again, it was a time when we were still heavily involved in Vietnam. And so why should I be fighting for the rights of people in the military now. With eight million people on active duty, you’re talking about a group of at least 800,000 people who need their rights defended. And another point that’s not usually made is that most of these people are from poor, lower class backgrounds and they don’t have the ability to defend themselves and they don’t have any advocates. And the military gets away with a lot.

So at any rate, the trial… Really, the high point to the trial was my father’s testimony.

EM: Well, how did he wind up on the stand in the first place?

CB: I asked him to testify, but nobody knew what he would say. And he said he wanted to when I asked him. And I just decided it didn’t matter what he said. He was my father and he was a career military officer and he should take the stand. Well, what he said was about as revolutionary as anything anybody could have said and yet incredibly supportive. He testified that he thought that my sense of personal honor was higher than his own. And that the reason I was in trouble was because I had been asked a question and I had told the truth. And he didn’t think I should be punished for having told the truth.

He then went on to say that he knew of undetected homosexuals who served as openly gay combat marines. And the prosecutor was just nonplussed. He couldn’t believe it. He said, “And there was no discrimination?” And my father said, “No, of course not.” He said, “Those people live together in foxholes and they fight side by side.” And he said, “Who cares who you sleep with? It’s not a factor. Race is not a factor in Vietnam. These people, quite in contrast, if they thought there was discrimination, they would band together to protect the guy who was being discriminated against.”

And there was a wonderful section where he says, “If I hold a man in my arms and kiss him on the forehead because he’s dying,” which he’d done. His whole job in Vietnam was just giving last rites. He says, “Does that make me gay?” He said, “How are we going to define this? Am I never allowed to show affection to another human being?” And then he went on to say that he knew of undetected homosexuals serving in the ranks of commander, captain, and rear admiral, and that you’d better be careful who you criticize because your boss might be gay. And that made the front page of every paper in the country.

And, um, the sad part of it was he was then severely criticized and, I think, severely punished for all the wrong reasons. His Navy chaplain colleagues criticized him for what they thought was betraying a professional trust. They felt that people had confessed to him as a clergyman and he had betrayed that trust by saying in public that he knew of people who were gay.

My father just blew up. He said, “I didn’t betray any professional trust.” He said, “The only thing I was testifying about were people who had made passes at me.” And he was just furious. To the day he died he was furious about what the church had done to him. Because the Navy chaplains and the national Presbyterian structure all turned their back on him. They just ostracized him. Didn’t help him get a job. Wouldn’t talk to him. Wouldn’t return his phone calls.

And then he got cancer from the Agent Orange. And was retired, theoretically for the cancer, but he’d already been passed over, which would have forced him to retire.

EM: Passed over for promotion.

CB: Right. And that was it. And it was only shortly before he died, long after the trial was over, that he revealed to me that he felt that the church had failed him, that the military had failed him, and virtually all of his friends had failed him.

Now that’s not to say we didn’t get good support. There were a lot of people who were a hundred percent behind me and a hundred percent behind the family, but they didn’t tend to be organizational types. It was not the establishment that was behind us at all.

EM: That must have shocked him.

CB: It really did. I mean, he gave up God. He just turned his back on the whole thing. He retired and went down to the Outer Banks of North Carolina and opened a hunting and guide service for duck hunters and carved ducks until the day he died. He finally said the only place he felt comfortable was alone on the marsh in a boat with a dog and a gun. And he would go out all day every day and sit there all by himself.

EM: How did that hit you?

CB: I was furious. I still am. He died an absolutely broken man. It’s clearly a case of the sins of the son visiting the father.

———

EM Narration: In the end, Copy Berg’s father’s testimony didn’t make a difference. Copy got a less-than-honorable discharge. No back pay and no veterans’ benefits. But through subsequent appeals, Copy’s discharge was upgraded to honorable, and he eventually accepted a financial settlement from the Navy.

By then, Copy had settled in New York and launched his career as an artist. In 1986, Copy and his longtime partner, the writer Paul Nash, were both diagnosed with HIV. Paul died in 1993.

Copy Berg died of complications from AIDS on January 27, 1999. He was 47 years old.

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: senior producer Nahanni Rous, producers Josh Gwynn and Janelle Anderson, deputy director Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Jeff Towne, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Denio Lourenco. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman and our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season six of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Small Change Foundation, Irwin and Andra Press, and our listeners, including Mike Winerip. Thanks, Mike!

Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. Our website is also where you’ll find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

So long! Until next time!

###