Sara Boesser

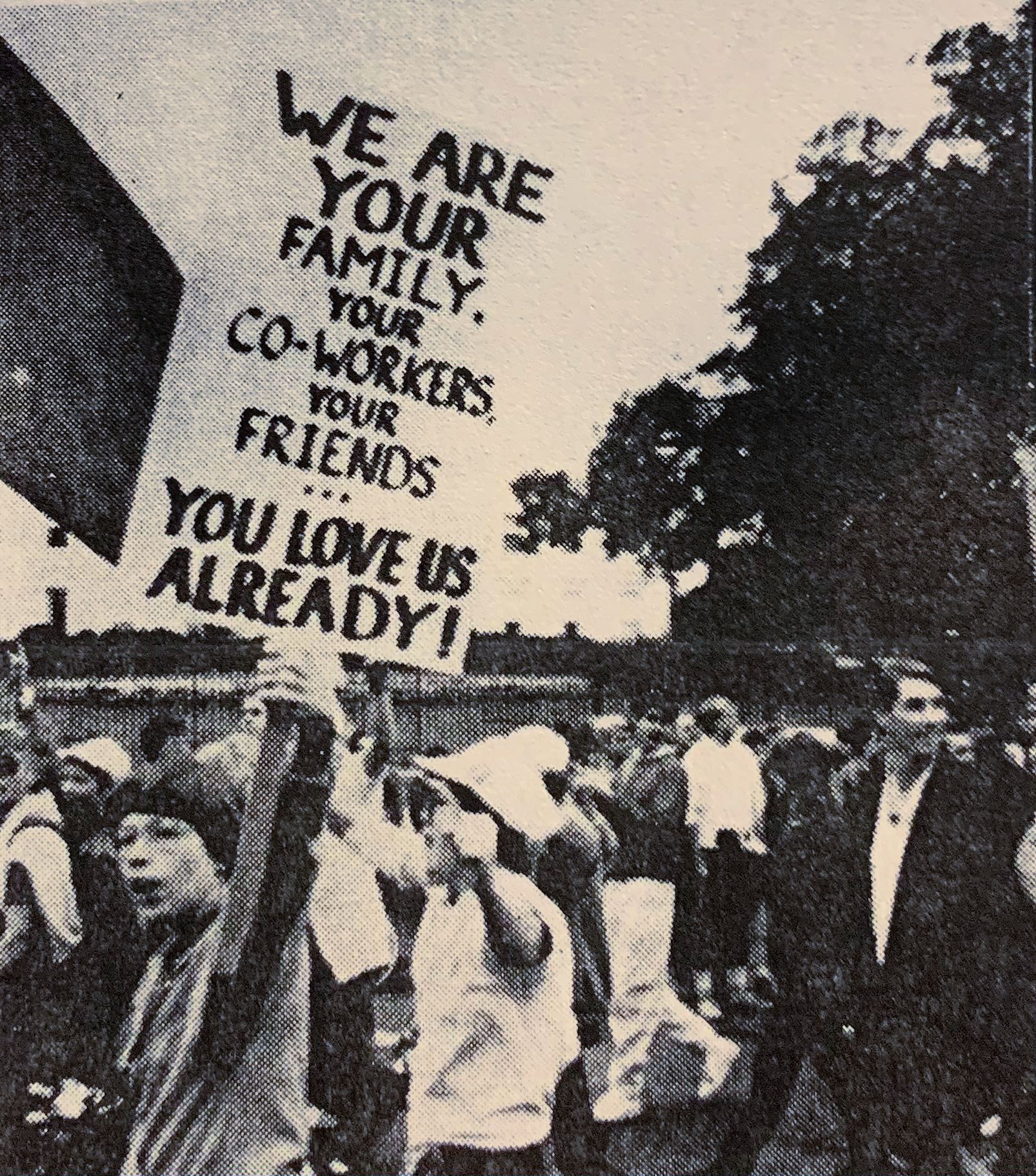

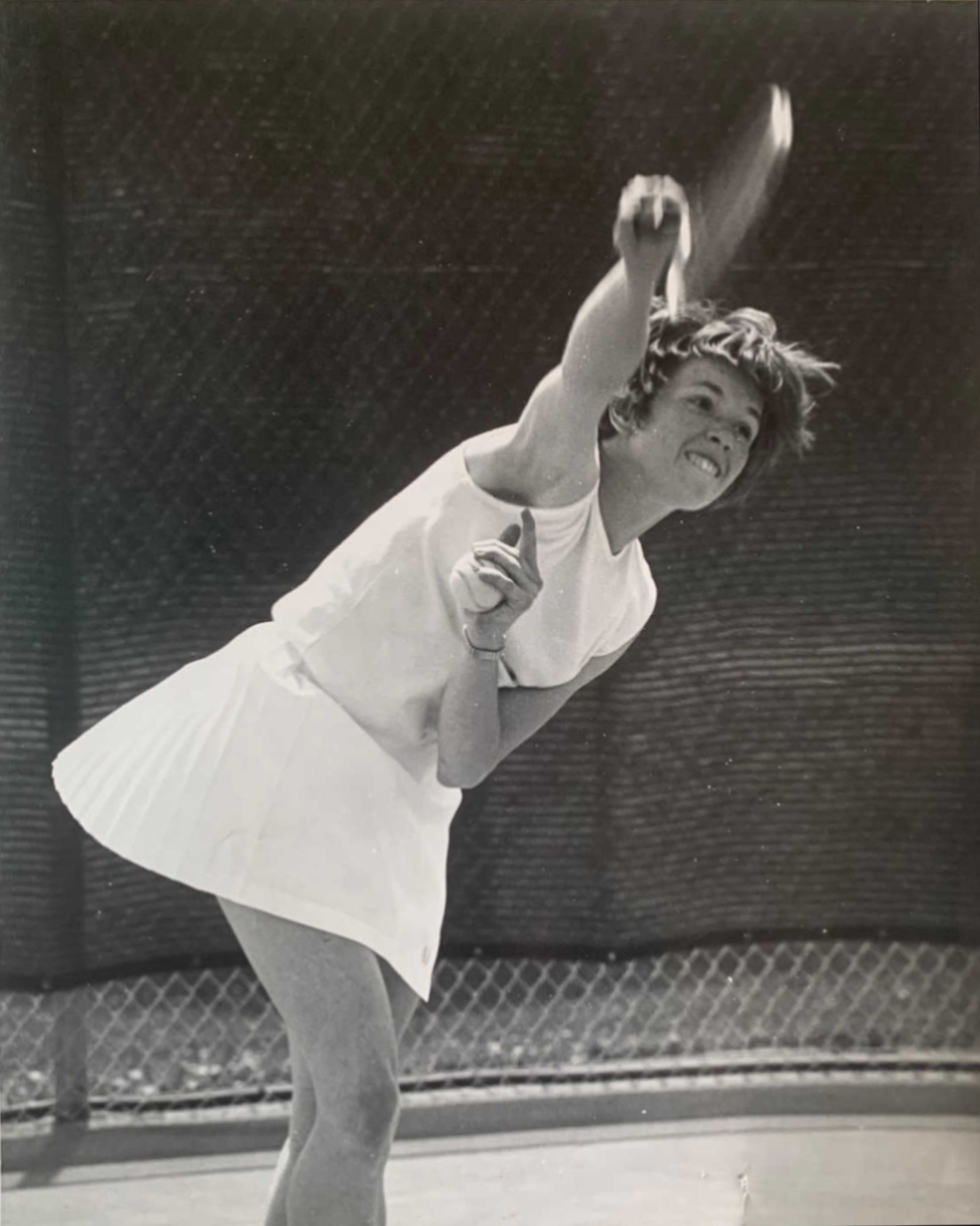

Sara Boesser at the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, Washington, D.C., October 11, 1987. Credit: Courtesy of Sara Boesser.

Sara Boesser at the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, Washington, D.C., October 11, 1987. Credit: Courtesy of Sara Boesser.Episode Notes

From her home in Juneau, Alaska, Sara Boesser watched with alarm as the AIDS epidemic rolled across the lower 48 states, threatening lives and hard-won gay rights. The soft-spoken building inspector decided there was no time to waste. She became an activist and got to organizing.

———

Sara Boesser first got involved in LGBTQ organizing in the latter part of the 1970s, while she was living in Seattle. That’s where she became a member of the Dorian Group, a local organization founded in 1975. To learn more about the Dorian Group, read this short history of Seattle’s LGBTQ movement, have a look at one of their newsletters from 1976, and watch this excerpt of an oral history interview with one-time Dorian Group president Roger Winters. You can also read about the Dorian Group in the oral history of Charles Brydon, the organization’s founder, in the two editions of Eric Marcus’s Making Gay History book.

After she’d moved back to in Alaska in 1982, Boesser began reading about a mysterious disease that was killing gay men. Inspired to act, she became a founding member of Shanti of Juneau, a community-based organization patterned after Shanti in San Francisco that sought to educate the public and give support to people infected with HIV. You can see their old website here. In the episode, Boesser describes delivering a Shanti AIDS education talk to the Soroptimists, a volunteer service organization for women; you can learn more about their history here.

The episode touches on the resentment that some lesbians expressed during the early years of the AIDS crisis at having to take care of their male counterparts. You can read one woman’s perspective from 1983 here. But far from deepening rifts within the LGBTQ movement between lesbians and gay men, fighting AIDS brought these communities significantly closer, and the lesbian community became a pillar of strength for people with AIDS early on. Watch AIDS activist Sarah Schulman talk about the unification in the movement in this short clip from Rosa von Praunheim’s 1990 documentary, Positive.

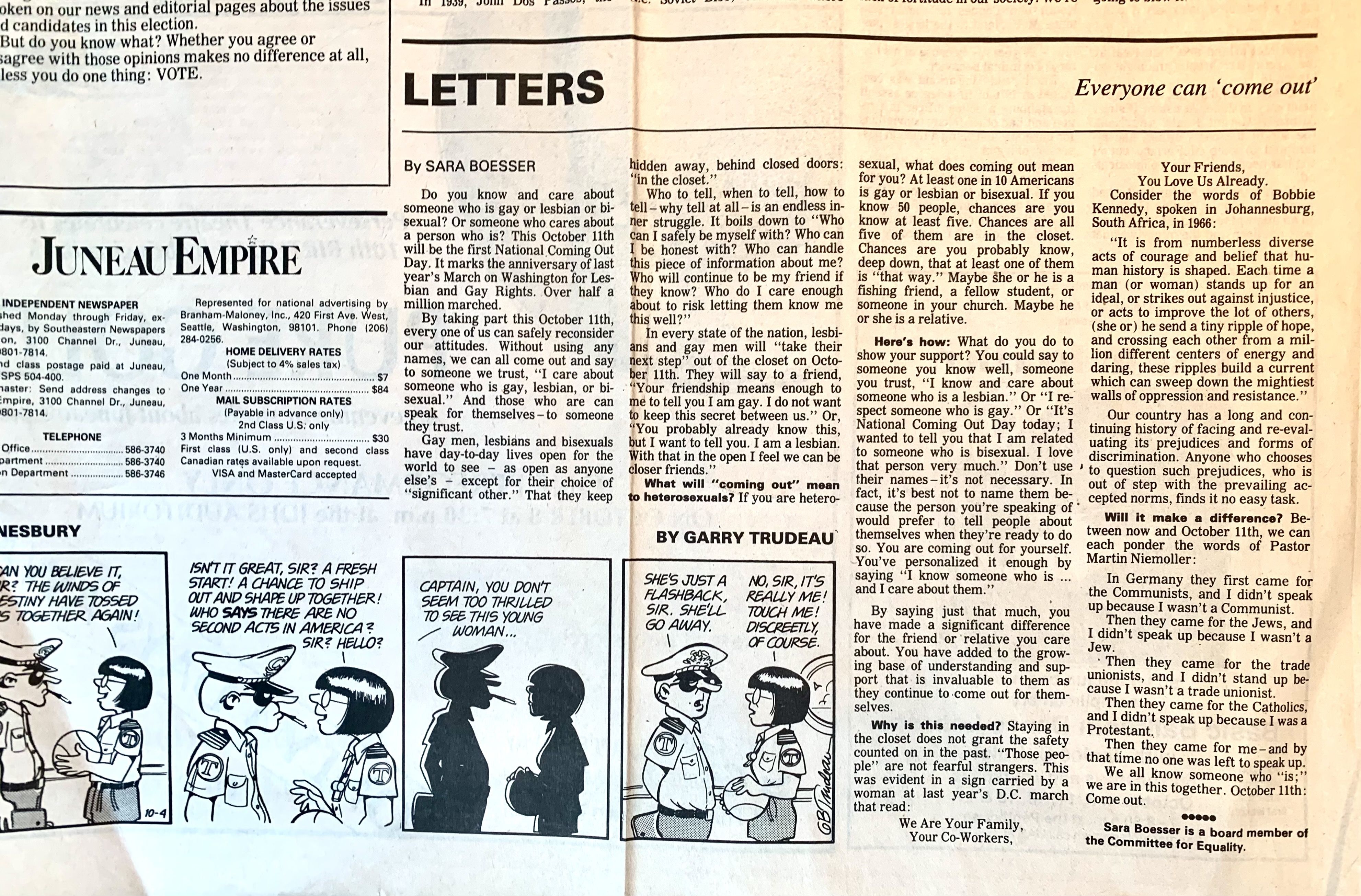

Boesser was also a founding member of the Southeast Alaska Gay and Lesbian Alliance (SEAGLA). And she became president of the Committee for Equality, a state-wide board that worked to safeguard domestic partnerships and advocated for same-sex marriage. After decades of work as a tireless champion of LGBTQ rights, Boesser was present for the passage of Juneau’s equal rights ordinance in 2016. To learn more about Alaska’s LGBTQ civil rights history, have a look at this article and timeline.

Boesser also started the Juneau Pride Chorus, and for many years she gathered LGBTQ-related news items for the blog Bent Alaska in a section called “Sara’s News.” In 2004, Boesser’s book, Silent Lives: How High a Price?, was published. In it, she reflects on the hardships of LGBTQ repression and provides a roadmap for communities to communicate openly.

In 1990, Boesser’s parents moved to Juneau and together they helped start a local chapter of PFLAG. Her mother, Mildred Boesser, spoke on panels and testified repeatedly to government officials in support of LGBTQ rights and marriage equality. A religious woman, she defiantly told legislators that she believed homosexuality was a “gift of God” (see page 9 here). SEAGLA honors her decades of advocacy through its yearly Mildred Boesser Equal Rights Award. Learn more about Mildred Boesser here.

Until she retired in 2007, Boesser worked for the city of Juneau as a building inspector and an ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) specialist. In 1993 she received a patent for a system she’d developed to make small boat harbors with significant tidal swings accessible to wheelchairs. She released the rights to the patent to the public domain so anyone could use it without cost.

Boesser’s story was featured in the original edition of the Making Gay History book in a chapter titled “The Brave Alaskan.” For more stories about lesbians who, like Boesser, got involved in AIDS activism, explore TheBody’s collection of interviews “Lesbians on the Front Lines” and have a look at this brief PBS video about fierce pussy, a collective of queer women artists and activists who got their start in ACT UP.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

Back in 1988 as I started work on my oral history book about the LGBTQ civil rights movement, I was determined to include a mix of voices from places other than just the major East and West Coast cities. But I had a limited budget, so I had to choose carefully and combine multiple cities into the few trips I could afford.

Once I had interviews lined up in California and Washington State, I decided to add Alaska, which I thought would provide an unexpected and rarely heard perspective on the movement. The fact that my best friend Leslie lived in Juneau may have factored into my decision as well. She had just given birth to her first child so a visit to Alaska meant I’d also get to meet baby Jane—and I’d have a free place to stay.

In Alaska is where I met Sara Boesser, a soft-spoken activist in her late thirties who was drawn into the LGBTQ civil rights movement by the AIDS crisis. Watching from Juneau as the AIDS epidemic swept across the lower 48 states, Sara joined with other local lesbians and gay men to organize and prepare for when people in their own community would begin to fall ill.

That’s how Sara became a founding member of Shanti of Juneau, an organization patterned after the Shanti organization in San Francisco, which supported people diagnosed with HIV/AIDS during the early days of the epidemic. She was also a founding member of SEAGLA—the Southeast Alaska Gay and Lesbian Alliance. And at the time I interviewed her, Sara was president of the Committee for Equality, a state-wide board that worked for equal rights for LGBTQ Alaskans. She also worked full-time for the city government as a building inspector.

So here’s the scene. Sara picks me up in front of the Baranof Hotel in downtown Juneau and we drive out to the Mendenhall Valley to the modest cottage where Sara lived with her then partner. Sara bears an uncanny resemblance to one of my high school friends, with her Dorothy Hamill-style wedge haircut, oversized glasses, and her woodsy jeans and sweater outfit.

Sara is understated and self-effacing, but once we sit down to talk I quickly discover that she’s a savvy behind-the-scenes organizer. And she’s unwavering in her advocacy, even if that means going way beyond her comfort zone.

I start out by asking Sara when she first learned about homosexuality.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Sara Boesser, Saturday, November 18, 1989, at 2 p.m. At the home of Sara Boesser in Juneau, Alaska. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Sara Boesser: When I was, um, like a junior in high school, I think I first heard the word “gay” and asked what it meant. Within an hour I had decided that’s what I was and I was real excited to know that I fit somewhere.

EM: Had you thought up to that point that there was something wrong?

SB: I just knew that I was, um, not traditional in that I wasn’t dating boys. I have three younger sisters and I just was definitely out of step with their interests, and my, many of my friends’ interests, in boys. And I just, I had a sense that I was sort of an odd duck. But then when I heard the word “gay” and the description of it, you know, two women who spend their lives together or two men who spend their lives together, I thought, alright, that’s perfect!

EM: That’s it.

SB: Yeah.

EM: This would have been the 1960s.

SB: That would have been 1968.

EM: 1968. Did you, did you hear anything in 1969, was there anything published here about what went on in New York, the riots?

SB: Not that I heard of in Juneau. Juneau back then only had one TV station and we got all the news, like, two weeks later than the lower 48, as we call it. We didn’t get a lot of current news. And at that age I didn’t read the papers consistently so…

EM: Right. Were you fearful at all when you realized what, where you fit in?

SB: My realization was that… It was just like a, an hour in time. I took my dog for a walk and I thought about the conversation. Realized that, that gay was what I was. My parents weren’t gonna like it. But that was okay. So it wasn’t scary. It was kind of exciting, but I didn’t talk to anybody about it for a couple of years after that. It’s just like, I, I knew that it was sort of hush-hush just from the tone of the conversation where it had come up…

EM: So when did you finally talk to somebody about “it”?

SB: “It.” The big “it.”

EM: The big “it.”

SB: When I was a freshman in college. Yeah.

EM: Mm-hmm. You started college in ’69?

SB: ’70.

EM: ’70.

SB: Mm-hmm. I sort of put out feelers. I’d talk about unusual women or women who liked women. And nobody ever responded with the type of response that thought, that I thought I could go any further with, so… Actually, probably the first person I really talked to about it was, um, somebody I met on an archaeological dig, who also, it turned out, was, was a lesbian. And, uh…

EM: Here in Alaska?

SB: No, that was down in, in Washington State actually. And we were a whole summer at a archaeological site. It was great to have somebody to, to be open with. It was a real wonderful feeling.

EM: Someone with whom you could be yourself.

SB: Yeah. Right.

EM: How then did you move from, from that stage of your life to…

SB: Well, I started school… I left Juneau—graduated from high school and I left Juneau. Um…

EM: Where did you go to school, college?

SB: First I went to Stockton, California, University of the Pacific. And then I went to University of Oregon. And then I moved to Seattle to finish up a degree in anthropology. I’d sort of made a commitment to myself that I wasn’t gonna move back to Juneau unless I came back with a partner. Because when I left I didn’t know if there were any other women in, lesbians in Juneau. And even at that young age I thought it wouldn’t, it would be very lonely to be here as a lesbian. So I ended up in Seattle, and so I moved there in 1973 and stayed until 1982 when Carol and I moved here.

EM: Did you have thoughts then on, on the issue of gay rights?

SB: It’s funny, you know, um, when I was nine—in 1975 or early ’76, I was living with my partner in Brier outside of Seattle.

EM: Carol.

SB: No, another par—Susan was her name. My partner at that time. Um, and, uh, we were living in a little tiny one-bedroom house that had only wood heat and only cold running water, and life was not easy. And, uh, we were sort of talking about aspirations or future or something, and I said, “Well, someday, when I get to be an old fart, I’m gonna be a gay rights activist,” which seemed totally out of line with my past or my—that present even.

EM: What about being an activist interested you? What was there that wasn’t right that needed to be corrected?

SB: Well!

EM: Now there’s a question.

SB: There’s a question. Well, uh, the fact that, um, I had to lead a double life. I’d been raised to be an honest, outgoing, inclusive, sincere individual. And I had come to this point in my life where I could not be all those things with most people anymore because if I got to know them too well they would know about me being gay and I would either run the risk of losing that person as a friend or as an associate who’s easy to work with. So I started having to be more withdrawn and less sincere and less direct.

And, and, uh, people still liked me and people still respected me and people still thought I was a good person. The fury was, people could like me and hate gay people and that I was being quiet about it. So some day I knew I had to speak up. But I thought I was gonna put it off until I was an old fart. But AIDS came, see. And I realized you can’t postpone forever what’s important to you because you might not get to be an old fart.

EM: Mm-hmm. You moved back here in ’82. And at the time you had no specific plans about getting involved in gay rights activism or…

SB: Uh-uh. I really… From that conversation at that little house in Brier, I didn’t do anything about gay rights except get on various newsletter lists.

EM: Mm-hmm. What was it that changed things then, when you decided to speak out?

SB: Well… I guess the first thing that happened was I started reading about a lot of, uh, gay men were dying around the country from this unknown disease, AIDS that, uh… And some of the horror stories were coming through of not only were they ill and dying from this frightening disease, but they were also being abandoned by their families and losing their jobs and losing their insurance, and legislation was on the horizon to quarantine homosexual people, et cetera. And, and, uh, I and Carol and Frank and Scott and a couple of other friends, Carolyn and Marylou, we just, uh, we got together an AIDS training seminar here for the city of Juneau.

EM: Before we get to that…

SB: Yeah.

EM: … uh, this was not a, a women’s issue, though. Why then were you, why, why did it become an issue for you?

SB: Well, the issue for me was that, uh, homosexual rights were at stake. And it occurred to me that if the men lost their rights, I lost mine. But more than that, it was like, they’re being discriminated against not just because they’re sick but because they’re homosexual. I’m also homosexual and I need to stand up with them or else it’s just them and it’s only half the picture. I don’t know, it just didn’t seem right to stand by and let them take all of the heat.

EM: Mm-hmm. So how did you go—did you call a meeting? Did someone else call a meeting? How did it, how did it come about?

SB: Somehow they put out a call—I don’t know how the grapevine works, I don’t know where it started exactly, but—to the, uh, gay men and lesbians in Juneau.

EM: That was the first time you, you all got together.

SB: That was the first time I knew there, I saw gay men’s faces and knew they were gay in Juneau. I saw a lot of my women friends, and…

EM: Uh-huh. Did you have a sense of impending doom at that point about…? ’Cause I, it’s hard to imagine being here ’cause I was in New York and we were surrounded. We didn’t see AIDS coming from, uh, from a distance. It was just there. Um, did you have a sense of being here and watching what was happening in other parts of the country, uh, and, and feeling a need to prepare? Was that any…?

SB: That was a big part, a need to prepare. And actually we did gear up to take care of people. And what we ended up doing instead was mostly educating people, putting on trainings. Because the numbers of people who were ill in Juneau did not go up as we expected.

EM: Mm-hmm. How did people react to you when you went out? Any particular place that stands out in your mind that you went to speak?

SB: Oh, the Soroptimists, they were my favorite.

EM: The what?

SB: The Soroptimists. It’s a women’s group. It’s like a philanthropic group, um, educated businesswomen types, church women, and—you know, the upstanding women of the greater Juneau community. Uh, they wanted an AIDS education talk during their lunch. And so I got it set up for me to go as sort of—I was co-coordinator of Shanti at that time—and then I had one of our nurses, Kim, who was going to speak with me.

Well, Kim canceled at the last minute, and there it was just me, and I had never done the, the medical part, the safe sex part, the how to use condoms and all that stuff. And I, and here’s these women eating their lunch right in front of me, and I got going, and, and I, uh, I just remember I was embarrassed and they were embarrassed and we kind of all chuckled about it. But they did good. They were a responsive group. But they looked a little a—astounded at some of my brochures and my comments.

EM: Were they aware that you were a lesbian?

SB: No.

EM: No.

SB: Not directly. See, that was the thing with Shanti was that, um, it seemed important to keep, uh, Shanti—to keep the lesbian/gay men issue sort of subdued in Shanti so that we could get heterosexual people to be involved, too. And, so that our outreach would be accepted by the greater community and people wouldn’t view us just as a gay and lesbian group or view our services as just for gay men.

EM: What of the argument—and I, and I had heard this particularly in the organized communities in New York and Los Angeles—that once again women are being put in the position of taking care of men. That men make the mess and women clean up. And here’s the AIDS mess. The men couldn’t keep their pants zipped, and now the women are here taking care of them. Um, and I’ve heard this expressed a number of times and read articles about it. Uh, any thoughts on that?

SB: Yes.

EM: Aha!

SB: Aha! Um, actually, I think… I don’t know, I guess I’m sort of thinking it’s not fair to get mad at the men for doing something that caused AIDS when they didn’t know it was causing AIDS when they were doing it. I think that’s—it’s, like, it’s Monday morning quarterback, or, whatever, Tuesday morning quarterback. You can’t say you shouldn’t have thrown the pass. Didn’t know. The guy was gonna intercept it, let’s face it.

Uh, I agree that a lot of women end up taking care of men per se as part of this AIDS struggle. I felt resentful at first when I first thought about it. And in retrospect, you know, I think that AIDS made me realize I can make a difference. We took individuals, put them together, got state grants. We’re an organization now, and we’re respected by health and social services and ministers and… We, we let ourselves shine and we were respected.

I think I gained incredible courage. I mean, if I can talk about AIDS on TV, I can probably say to somebody I know and care about, “I’m a lesbian,” you know? There’s…

EM: Has AIDS had a positive or negative impact on gay rights issues…

SB: … on gay rights issues…

EM: … ultimately, do you think, looking at it now, just from your own experience?

SB: From my own experience?

EM: Yeah.

SB: I, I think that ultimately it’s going to be positive in that, um, gay men and gay, and lesbian women will have connected. We’ll work together, we’ll get to know each other. I think both sides will gain courage and learn to lobby for what they believe in and, and learn to stand up for what they believe in. But, more important, on a personal one-to-one level, I think, uh, the whole nation’s talking about sexuality. Um, if people keep coming out, partly as instigation of AIDS, you know, has forced people out of the closet—you know, “Hi mom, I’m, I’m sick and, by the way, I’m homosexual”—you know, a lot of parents have had to come to terms with this. I think what’s been hidden has become less hidden as, as a result of AIDS, and…

Uh… It shouldn’t have had to happen this way, though. When I was, uh—how old was I?—I used to… When I was, like, in college or something, I had this idea. I thought, it would just be great if, um, some day, uh, everybody who was gay would just wake up and have green hair. And we’d all have to go to our jobs and all have to go to school. And everybody out there would look and say, “Oh, I know somebody who’s gay.” Well, and then they’d, they’d get over it and life would go on and we, we wouldn’t be such a scary enigma.

Well, that didn’t happen. AIDS came instead and I think that’s kind of the same thing. But two things have happened. We didn’t all just wake up with green hair. A lot of people also woke up with light green hair, like our supporters, you know, our hidden supporters. Our parents, you know. There’s a bigger, there’s a bigger turnout than, than we would have expected. So for all those people that are dying, that’s not the way we wanted it, but I think it will have a positive effect on our lives some day.

EM: Thank you, Sara. It’s a high price, an incredible price, um, but I think you’re right.

SB: It’s a terrible price, but for those of us who are living, do something with it, you know?

EM: Thank you.

SB: Phew.

———

EM Narration: In the years after I interviewed Sara Boesser, she became a highly recognized statewide activist on a range of LGBTQ-related equal rights issues, and for a time was the board president of the Juneau chapter of the League of Women Voters—the first out lesbian to hold that position.

Sara even inspired her parents to pick up the activist ball. In the 1990s they helped found the Juneau chapter of PFLAG. And Sara’s mother, as a vocal proponent of LGBTQ rights and marriage equality, often testified at the state capitol and campaigned door-to-door at her daughter’s side.

Sara is now retired and lives with her spouse Juanita in New Mexico. When I asked her what drew them to New Mexico, she explained that they fell in love with the landscapes, food, cultural diversity, and the abundant sunlight. Having interviewed Sara in the gloom of an Alaska November, I get it.

———

Thank you to everyone who makes Making Gay History: story editor Inge De Taeye, associate producer Ali Lemer, audio engineer Cathleen Conte, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael LeClerc, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Special thanks to our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner Jenna Weiss-Berman. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division for their assistance. And thank you to Con Edison for their generous support of our education work.

Season ten of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation; the Calamus Foundation; the Kipper Family Foundation; Christopher Street Financial; Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson; Bryan, Christine, and Alex White; and scores of other individual supporters.

Head to makinggayhistory.com where you’ll find all our previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

And please keep those five-star iTunes ratings coming so more people can discover our proud history through the voices of the people who lived it. Making Gay History has been downloaded in more than 200 countries and territories around the world, and we appreciate your emails from near and far, especially a recent one from a young gay man in Libya. Thank you for writing and for reminding us that there is so much work yet to be done until LGBTQ people are free to be themselves the world over. You’re in our thoughts.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###