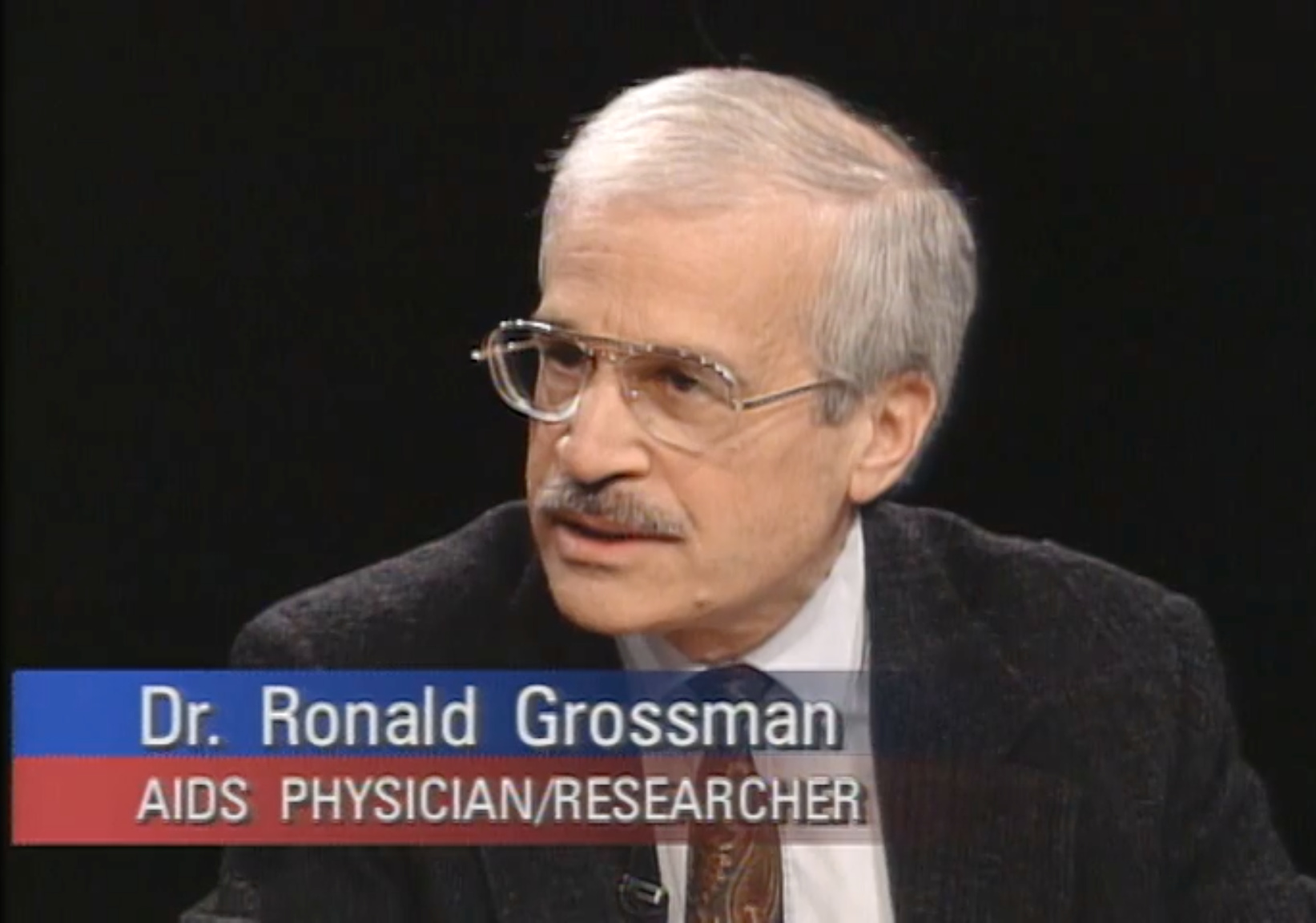

Dr. Ronald Grossman

Still of Dr. Ronald Grossman during a panel discussion about AZT on the Charlie Rose talk show broadcast on April 5, 1993. Credit: Charlie Rose LLC.

Still of Dr. Ronald Grossman during a panel discussion about AZT on the Charlie Rose talk show broadcast on April 5, 1993. Credit: Charlie Rose LLC.Episode Notes

Dr. Ronald Grossman treated his first AIDS patient before the disease even had a name. But with a New York City practice serving predominantly gay men, he would soon become an expert on the disease. By the time life-saving treatments became available, hundreds of his patients had died.

———

In the episode, Dr. Grossman talks about seeing his first AIDS patient in 1981, and speculates that the man might have contracted HIV up to a decade earlier. Scientists in fact believe that HIV was present in New York City by the early 1970s. In 1990, a team of doctors claimed to have discovered an AIDS case from 1959 in Manchester, England, but that was later disproven. Nonetheless, 1959 remains an important year in AIDS history: researchers were able to confirm the presence of HIV in the blood sample of a Congolese man who died in 1959, while another man died of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (a common opportunistic infection in people with HIV/AIDS) in New York City that same year.

Dr. Grossman also discusses the famous June 5, 1981, issue of the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), which detailed five young “active homosexuals” with pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. It was the first official medical report on what would come to be known as HIV/AIDS. Read the original text here.

The next year, a cluster study of early California AIDS patients linked a number of Los Angeles residents to an out-of-state patient designated “O”—for “Outside of California.” As noted by Dr. Grossman, that letter O was later mistaken for the number zero, which eventually gave rise to the incorrect Patient Zero theory that blamed Gaëtan Dugas, a French-Canadian flight attendant, for spreading HIV across North America. For more on this topic, have a look at the notes for our previous episode featuring Randy Shilts.

Patient Zero was not the only erroneous theory circulating about AIDS in the 1980s. Rumors and misguided reporting—some purposefully disseminated as part of a Cold War disinformation campaign (discussed in greater depth here)—linked HIV to secret government programs targeting gay and Black Americans. In the beginning, doctors had few answers for a worried public and false information spread rapidly. Watch Americans try to separate fact from fiction in this 1986 PBS special.

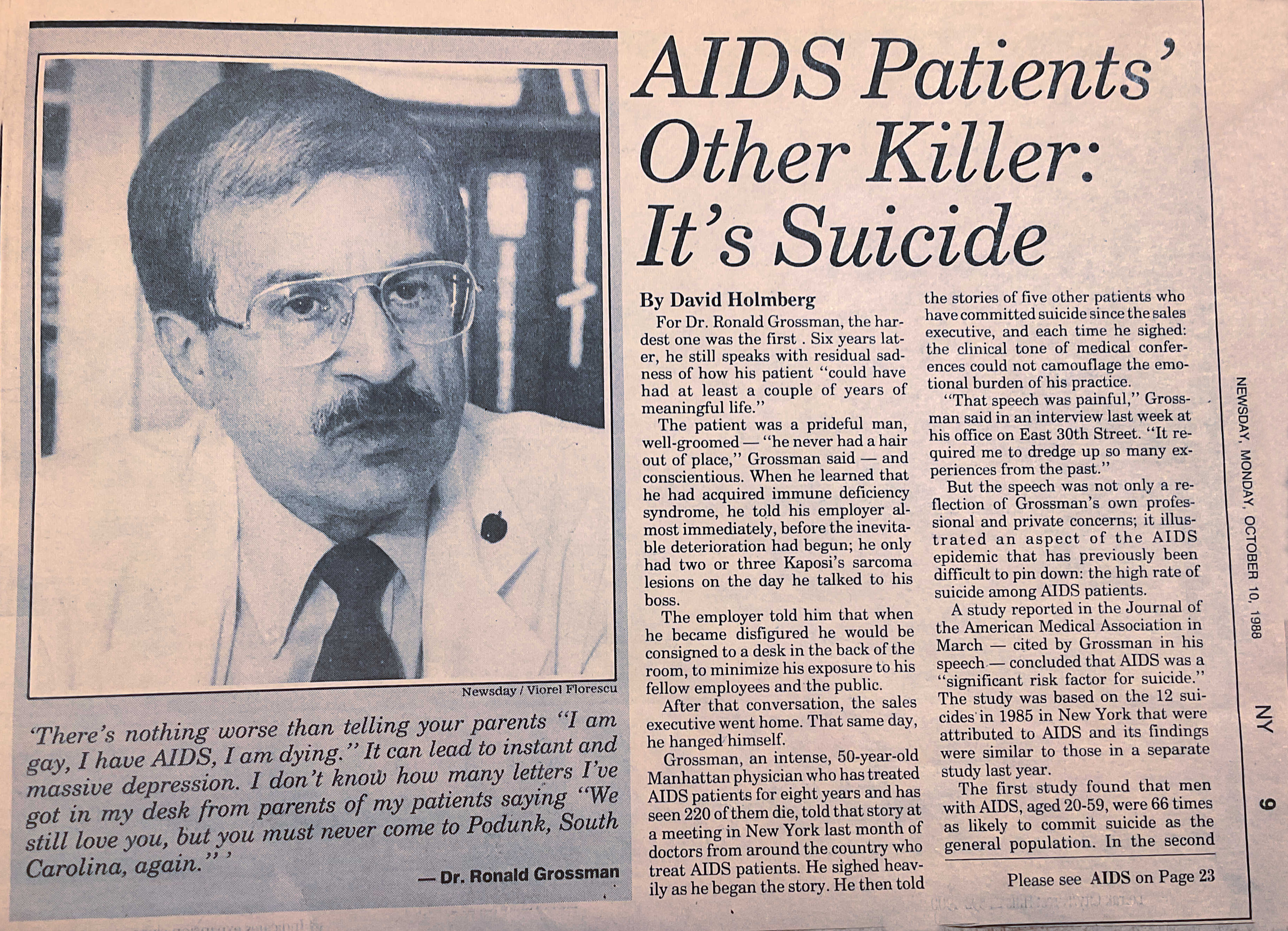

During the early years of the AIDS crisis, Dr. Grossman made frequent house calls to pronounce the deaths of patients who’d succumbed to AIDS. Despite small-scale efforts like the Gift of Love hospice in Greenwich Village, which was blessed by Mother Teresa in 1985, there was a dearth of end-of-life care for AIDS patients in New York City.

Dr. Grossman treated more than 1,200 patients with HIV, hundreds of whom died from related illnesses. Many other healthcare professionals have shared their memories of the early AIDS crisis. You can hear about the experiences of doctors in the Bronx here, learn the stories of nurses here and here, watch this documentary about two incredible doctors in Utah, or read AIDS Doctors: Voices from the Epidemic, drawn from the oral histories of 76 physicians, including Dr. Grossman. His and many of the other oral histories are available at Columbia University’s archives.

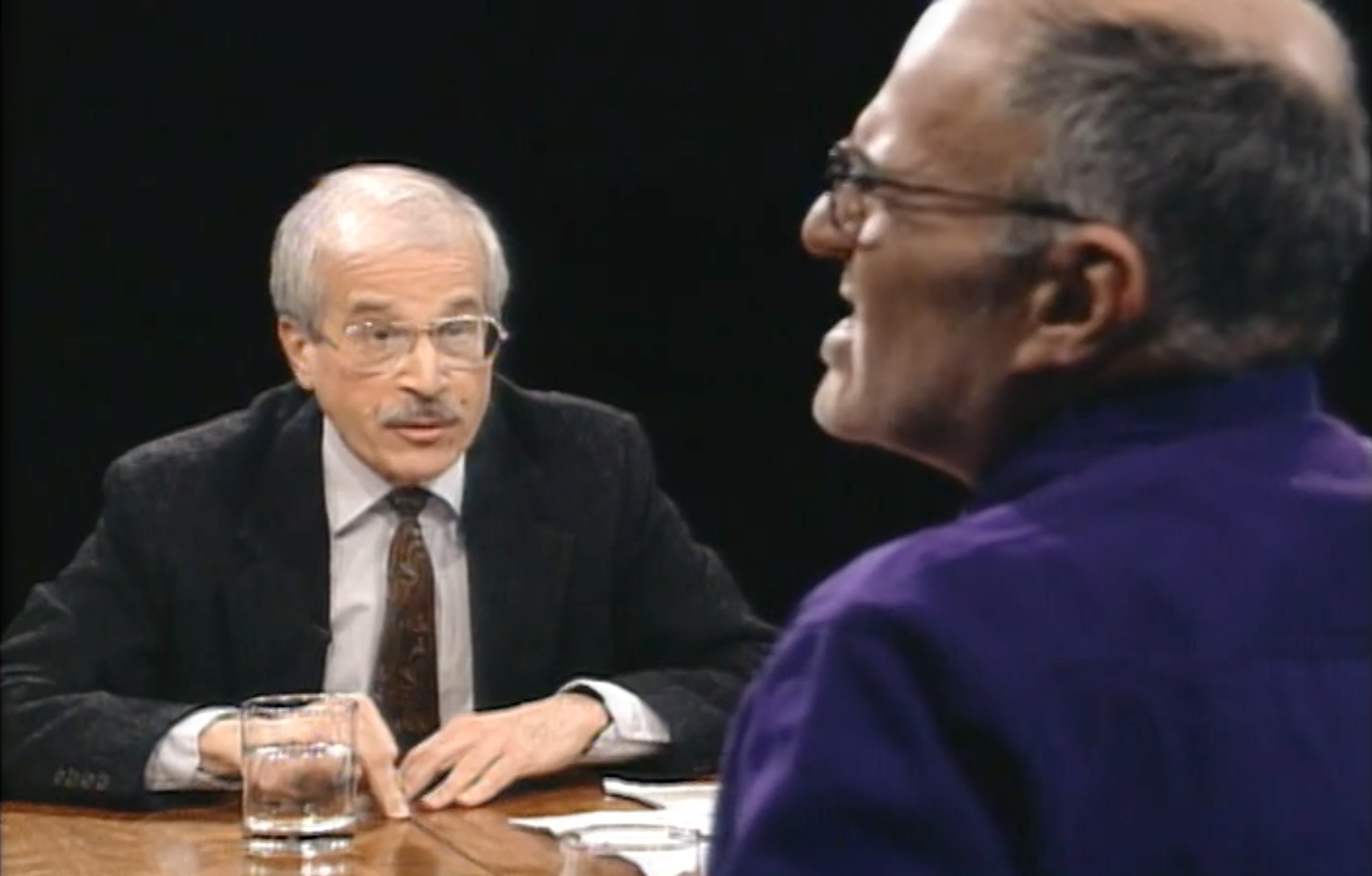

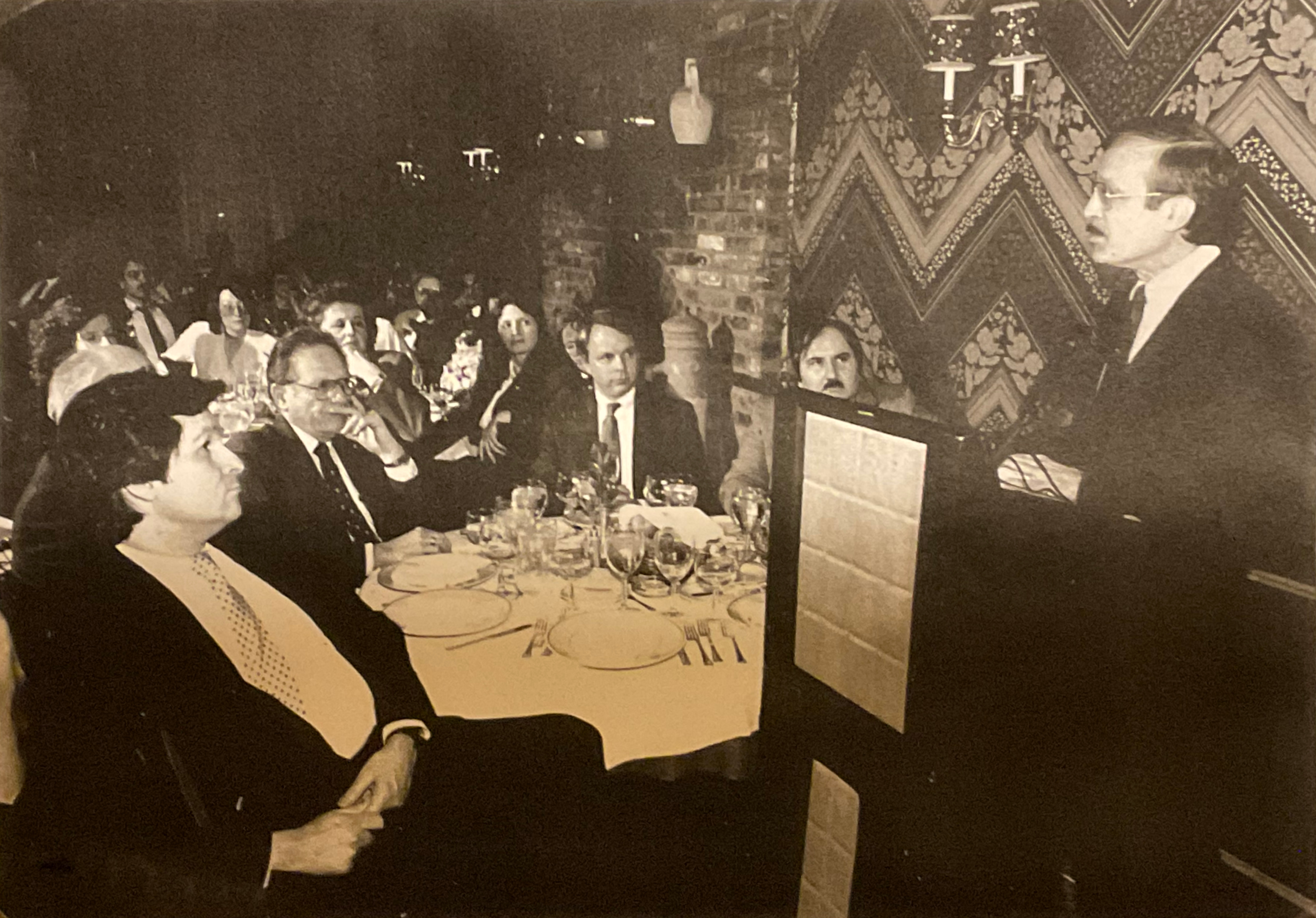

The episode references a 1993 episode of the Charlie Rose talk show on the efficacy of AZT, a controversial AIDS treatment, on which Dr. Grossman and activist and playwright Larry Kramer appeared as guests. You can watch the entire discussion here.

In addition to being Eric’s doctor, Dr. Grossman also cared for legendary film historian and activist Vito Russo, who was featured in this Making Gay History episode.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

Dr. Ronald Grossman lost his first AIDS patient well before anyone knew that we were witnessing the start of a worldwide epidemic. In the fifteen years before there were effective HIV/AIDS treatments, he lost hundreds more. Many of those patients were inherited from gay colleagues—friends who turned their medical practices over to him after they, too, got sick and died of the disease.

Dr. Ron, as I call him, has been my personal physician for nearly three decades. We’ve had many conversations about AIDS during that time—in the context of his work, as well as mine. We’ve even uncovered some surprising points of intersection. Like Vito Russo. Vito, who was the author of The Celluloid Closet and a cofounder of ACT UP, was one of the first people I interviewed for my Making Gay History book because I knew he was ill. The physician who tended to Vito in his final years, I later learned, was Dr. Ron.

Years ago, Dr. Ron confided that he’s kept the files of all his patients who died from complications of AIDS—reams of files, locked away in an office closet. Dr. Ron explained that he used those files when he found himself confronted with a patient who was in denial about AIDS. He would unlock the closet door, pull the chart of a 20-something gay man who had died, who had no underlying illnesses, no history of drug use, and say, “This is the reality of AIDS.”

I think of those files every time I visit Dr. Ron’s office—imagining the very real people behind all that paper. And I wonder what it must have been like to have known each of those men, to have counseled them, and to have treated their various opportunistic infections, only to see them waste away and die, most of them still in the prime of life.

So when we decided to devote a couple of podcast seasons to HIV/AIDS, Dr. Ron was one of the people I knew I had to interview. To find out what the early years of the AIDS crisis were like for a young doctor trying to save lives on the frontlines of a baffling, stigmatized, and devastating disease.

So here’s the scene. It’s the morning of May 17, 2021 and we’re in the middle of another pandemic. Covid infection rates are down for now so we’re able to meet with Dr. Ron in his busy office overlooking noisy Columbus Circle, just across from Manhattan’s Central Park. It’s an office I know well, from the blood pressure monitor and model skeleton to shelves filled with medical books and a football-sized 3D model of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Dr. Ron is sitting behind his broad desk near the examining table. He’s dressed casually in a brown V-neck sweater over a pressed shirt. And despite his thinning silver hair looks years younger than he is. Or, than I estimate he is. Dr. Ron made clear a long time ago that he’s not about to tell me his actual age.

We start by talking about Dr. Ron’s childhood in Omaha, Nebraska, where his ideas about what it means to be a good doctor first took shape.

———

Dr. Ronald Grossman: Let me tell you a quick anecdote. My family doctor was, we were so close to him that as a kid—because he treated me from like 10ish till adulthood—I thought he was a relative. And, and, uh, the pediatrician showed up at my medical school graduation, and in the receiving line, he, in a very loud voice, says to my mother, who was right next to me, “You owe me a necktie,” meaning me. My mother laughed so hard I thought she would collapse. Apparently, every time he examined me as a well baby, I peed on his necktie. Now I tell you those anecdotes because these are the kind of relationships I had as a kid. And I decided I want to emulate that. I want to reproduce that as a adult doctor.

Eric Marcus: What year did you arrive in New York?

RG: That’s unfair, Eric. I came here in 1971. Yes. So it’s 50 years not quite to the day. I came to New York chasing a, uh, a boyfriend. Okay? It wasn’t really my idea to move here, but he was in theater. Where else to go? Right. When I arrived here, I arrived with no connections whatsoever. And I literally just opened an office.

What I found early on, as I began to attract gay patients, is that the kind of medical care they were getting was quite honestly rather appalling. For the most part, the doctors who identified themselves as gay and had a lot of gay patients basically acted as STD clinics.

There was no depth. Um, the just, basics—physical exams and whatever, whatever—was simply not being done. And I said, okay, I’m gay and the clientele is going to be primarily gay, but to treat only STDs? Just wrong.

Well, the word got out that there was a real doctor in town. I know that sounds egotistical, but I’m fully trained and, you know, was excited to, to do it.

EM: Um, we’re going to jump way ahead ’cause I wanna focus specifically on, on the AIDS years. When did you first realize that something bad was happening?

RG: It is so clear in my mind. Did you know me when we had the office on, on, uh, on 30th Street?

EM: Yes.

RG: Yeah. Jeffrey, who was my number-one guy—who, by the way, uh, uh, is alive and well despite HIV—said, “You’ve got a really sick new patient in waiting room number,” whatever. I walked in and what I saw just didn’t compute. A very young fellow, a Latino from a Central American country, uh, severely wasted, high fever, obviously very weak.

And you can guess the rest I’m gonna tell you: the mouth was full of thrush, Kaposi’s lesions—and I had no idea what they were—all over. But that’s not the real story. The story was that I had walked him down the hall to that examining room and he could barely walk, with a look of pain on his face you can’t imagine. And when I examined him, the pain came from gigantic ulcers near his anus, untreated. And what was the rare disease causing this? Herpes. So everything he had was an exaggeration of—not that Kaposi sarcoma was ever seen before, but anything else that he had… His lung—he was coughing his head off and short of breath…

Will it surprise you that he survived possibly three weeks on a respirator at Bellevue? And it raises a very interesting question, and that is, if I saw him—and this is 1980, late ’81, right—with that advanced disease, when did he catch it? It’s very rare for HIV disease to move rapidly, right? So it literally pushes back the history of this epidemic with one patient, with one doctor, I’m gonna guess anywhere from eight to ten years, if not more.

And you probably know there’s plenty of speculation that indeed the disease goes back far, much farther than that. There are all manner of little hints of people with similar diseases that didn’t, however, connect as an epidemic. And that was a heck of a way to see the very first case of HIV. By the end of 1981, I had seen at least four or five more patients exactly like that. And needless to say, not one of them still alive.

EM: Did you know what you were dealing with with this patient? Had you already read the first…

RG: The famous MMWR…

EM: The Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report…

RG: … Weekly Report. MMWR, the publication of the CDC, right. That was the, uh, report of the so-called Los Angeles cluster. I believe it was five gay men, all presenting very similarly to the patient I just described for you, and none of them knowing each other. But they had a connection, right? This apparently very handsome airline steward. That airline steward has been described in the literature as Patient Zero, but he never was Patient Zero. The epidemiologists who tracked the other five people, he was the only one that lived outside of Los Angeles. So he was patient “O” for “Outside of Los Angeles.” And unlike the way the Europeans do it, by putting a line through the “O”… So the legend became Patient Zero.

EM: That would have been in June of 1981.

RG: Right. And when I read it, uh, it described my case of course to a T. Around the time when that MMWR came out—Dr. Dan William was another, uh, pioneer, uh, in HIV care, we sat together and tried to pick apart what’s causing this. And he came up with a term I’ve never heard anyone else use. He said, “This is immune overload. Something is damaging the immune system.”

Now he was very careful to not say, “Oh, it’s a virus,” because there was absolutely zero evidence for that. It would take well into 1982 before there was any kind of consensus that there was a “agent,” quote, causing this. And that’s the opening chapter.

EM: What did you think was going on?

RG: We just were as certain as certain can be that it had to be a transmissible agent. Whether or not it was aided and abetted by such issues as drugs and alcohol and lifestyle wasn’t clear… It just had to be, it was just way too random.

But eventually there were some telltale blood tests—not the HIV test, that hadn’t been invented yet; not the viral load, we didn’t have a virus to measure—but, uh, uh, telltale signs in other blood tests. I’ll never forget because I took care of a dentist—wonderful guy, handsome as hell—and he, this particular blood test, which was very simply the test which measures the total protein in the blood, the globulins were always elevated. Why?

Now this becomes a tutorial, but I’ll keep it brief. We don’t own one immune system, we own two. We own a cellular immune system—it’s exactly the target of the HIV virus, right? T cells et cetera. And we own a humoral immune system. The humoral immune system are antibodies and antibodies are all proteins. And so this elevation in the globulin fraction of the protein was a tip-off.

The dentist walked in super healthy, routine physical, and his globulins are off the wall. He’d be dead in another year or two.

EM: So were you advising your patients not to have sex or to practice a different kind of sex or wear condoms? What did you tell your patients?

RG: Of course we told them that. It was also useless. The answer was, please come in for regular testing; let’s catch the syphilis, the gonorrhea, the chlamydia… All we could do is plead: don’t add a burden to the already burden that we don’t know the name of yet, um…

EM: Why was it pointless to tell them to wear condoms or, or ha—or not have sex?

RG: Because it didn’t work. Very difficult to talk people into safe sex, right? They felt healthy. They looked healthy. What are you gonna do, screen the guy you just met in the, in a bar? That was, that wasn’t gonna happen.

EM: Were you afraid for yourself?

RG: Mm. I would come home at night and examine my own lymph glands to the point where I made my neck sore. And to which the then boyfriend pleaded with me, “Stop doing that.” We had no idea. If this disease had been airborne the way flu is, and now with our new virus, we’d probably none of us be alive, because this was a true pandemic, but it didn’t present itself the way the current one does and all the other major respiratory pandemics.

EM: So then over a period of years, how many patients did you see who had, who had HIV? Um…

RG: Really want to know?

EM: Yeah.

RG: I don’t have an accurate number, but probably in the order of 1,200 to maybe even 1,500. I based that number on the number of deaths. I actually kept every single chart. Uh, I have more than 500 charts of deceased.

EM: I wonder what was the impact on you as a, as a—I know you’re a doctor and so you deal with people who are ill, but what was the experience like of having patient after patient die?

RG: The deaths that we saw, Eric, were exactly what you would expect. Primarily in hospital; small percentage, much smaller than today, home or hospice. Hospice care was sparse in the early days in, in New York. And home required a lot of logistics, right. And yet, I uncovered a chart in which I am driving Kenny, my 40-year husband, uh, we’re driving to the theater. And I said, “Kenny, you know, I have to make a house call.” He says, “But his boyfriend said he died earlier today.” I said, “They’re waiting for me to pronounce.” So on the way to the theater, I’m stopping and making a house call on the Upper East Side to pronounce this fellow dead.

They didn’t want to call EMS. They wanted the family doc. And then that became at, at least a weekly event, to make a house call on someone who had chosen to forego hospital care. Which means I signed more death certificates than I ever dreamed of in my life. And by the time AZT came along, I had already lost a hundred or more patients that way.

EM: Right now during this current pandemic there, uh, there are a lot of people who don’t believe that it’s really a pandemic and it’s hard to persuade them. I remember you telling me that you sometimes showed patients charts of other patients to, to persuade them that this was real. Can you describe that?

RG: Including photographs. I mean, we’re talking about people who have really dug in their heels, right? There are people who felt, you know, that this wasn’t just a conspiracy; it was a vast conspiracy, particularly targeting gay men, right, um, uh, and prostitutes, of course, and other marginalized groups, and IV drug users, and on and on and on. And how does one, you know, talk them out of that?

Well, partly I would take a chance. Couple of patients took one look… I have a particular patient who begged me to show photographs of him, totally nude, totally covered with KS, before he died. And I had his permission in writing, right? I still have the pictures—I get teary-eyed just looking at ’em because he was this beautiful, wonderful guy.

I would say, “This is one way that HIV ends,” right? And, yes, it convinced a small number of them, but what eventually convinced them, Eric, you can guess: when the boyfriend got it, right? Boyfriend got sick fast. The other one remains asymptomatic. We still have patients like that.

EM: What was, how did the, the hospitals treat your patients when you first started seeing patients in the hospital?

RG: Um, to this day, Eric, I have an image in my head that I can never get rid of. It’s the yellow waste barrels. They looked like a very tall, uh, oil can, but they were yellow and they were exclusively for all the waste from HIV patients, including the fact that the linens were not laundered. They went into that barrel and got cremated, if, if you will. That’s how frightened hospital staff were.

How strange that we’ve come full circle: it’s precisely how hospital staff can catch Covid, right? But back then, we weren’t sure. So everything from, you know, gowns to sheets to pads to, to whatever got, got destroyed. So as you walked down the hall of either NYU or Bellevue, on the floors that were designated for HIV, it was just rows and rows of these yellow barrels.

I know it’s a trivial little, uh, visual, but it, it was a marker because we went from maybe, you’re on one floor with one barrel, by 1983, ’84, ’85, that, there would be dozens. Eventually they would designate entire floors, right, so often I could make a hospital call and see four or five or more patients on one floor. The one that sticks in my mind were the, uh, the boyfriends—they weren’t husbands in those days—in, uh, adjacent beds in the same room, so sick that they didn’t know their loved one was in the other bed.

And basically by that time they were mute, right? They were on every possible life support, from oxygen to parenteral nutrition to what have you, and, uh, they were just simply two of the most gorgeous guys you’d ever set eyes on in your life, right, who would, you would never have guessed would be dying in their late thirties, if they even got that old. And that just became a daily routine, Eric, to walk into one of those hospitals and see that.

———

EM Narration: I recently came across a clip from a 1993 episode of the Charlie Rose talk show, a round-table discussion about the efficacy of the controversial AIDS drug AZT. Dr. Ron was a guest along with the legendary AIDS activist and playwright Larry Kramer. True to form, Larry showed up spoiling for a fight and laced into Dr. Ron with a range of accusations. Dr. Ron didn’t rise to the bait. He patiently explained the science and never lost his cool. He was the thoughtful, engaging, and warm family physician I’ve always known.

Dr. Ron remains in private practice in New York City. Among his patients are many men who are long-term survivors of HIV/AIDS.

———

Thank you to everyone who makes Making Gay History, including story editor Inge De Taeye, associate producer Ali Lemer, audio engineer Cathleen Conte, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Special thanks to our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, who recorded Dr. Grossman’s interview. And thanks as well to our founding production partner Jenna Weiss-Berman. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division for their assistance. And thank you to Con Edison for their generous support of our education work.

Season ten of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation; the Calamus Foundation; the Kipper Family Foundation; Christopher Street Financial; Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson; Bryan, Christine, and Alex White; Mary Lefkarites; and scores of other individual supporters.

You can find all our previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature at makinggayhistory.com. And while you’re there, sign up for our newsletter so you know what’s coming up next.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###