Michelle Lopez

Michelle Lopez, 2020. Credit: GMHC.

Michelle Lopez, 2020. Credit: GMHC.Episode Notes

Women can’t get AIDS—or so Michelle Lopez thought until she tested positive for HIV in 1990. Viable treatments were years away, but the undocumented immigrant from Trinidad would not be defeated. She turned her diagnosis into an opportunity to help others while she fought for her life.

———

Michelle Lopez and Eric Marcus first met at a 2017 VideoOut storytelling event; watch Lopez’s set here. To learn more about Lopez, read this 1996 profile, listen to her discuss life after her HIV diagnosis, or watch her share her story to educate the public.

As a young bisexual woman, Lopez secretly read Audre Lorde’s book of poems Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. To learn more about Lorde, watch this short video, listen to this interview about her experiences as a young Black lesbian in 1950s New York City, or read her poetry.

When Lopez gave birth to her son, Rondell, in 1987, she overheard medical staff repeating a misconception about the HIV/AIDS risk of Haitians. The notion that Haitian people—along with homosexuals, heroin users, and hemophiliacs of the so-called “4H Club”—were more susceptible to HIV/AIDS originated with the CDC in early 1983. The belief proved unfounded. In April 1985, the CDC removed Haitians from their list of people at increased risk for AIDS, but the stigmatizing theory was hard to root out. It continued to shape federal AIDS policy, which led to this large-scale 1990 protest, and even reared its head in an alleged 2017 statement by former President Trump.

By 1987 AIDS was killing women faster than men after diagnosis. The short documentary Doctors, Liars & Women: AIDS Activists Say No to Cosmo shows how difficult it was to battle misinformation and an apathetic general public. By 1989 AIDS was the “leading cause of death among black women 15 to 44 years old in New York State and New Jersey.” Learn more about the history of women and AIDS here.

After Lopez learned she was HIV-positive, she started attending meetings of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), where she met activists Phyllis Sharpe (seen here at ACT UP’s 1990 Storm the NIH action) and Bob Lederer. Lopez also became involved in the Community Constituency Group (CCG) of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group, and testified on the importance of including women and children in clinical drug trials; you can watch her testimony at a 1997 AIDS Action Council forum here.

Lopez was also involved with the Lesbian AIDS Project (LAP), a group formed in 1992 by the Gay Men’s Health Crisis to give visibility to lesbians who were living with HIV/AIDS. They provided much-needed HIV education to at-risk women, trained leaders to educate the community about their unique challenges, and advocated for more research into woman-to-woman HIV transmission. Learn more about the HIV risks for women who have sex with women here and find out more about LAP in this oral history interview with its founding director, Amber Hollibaugh.

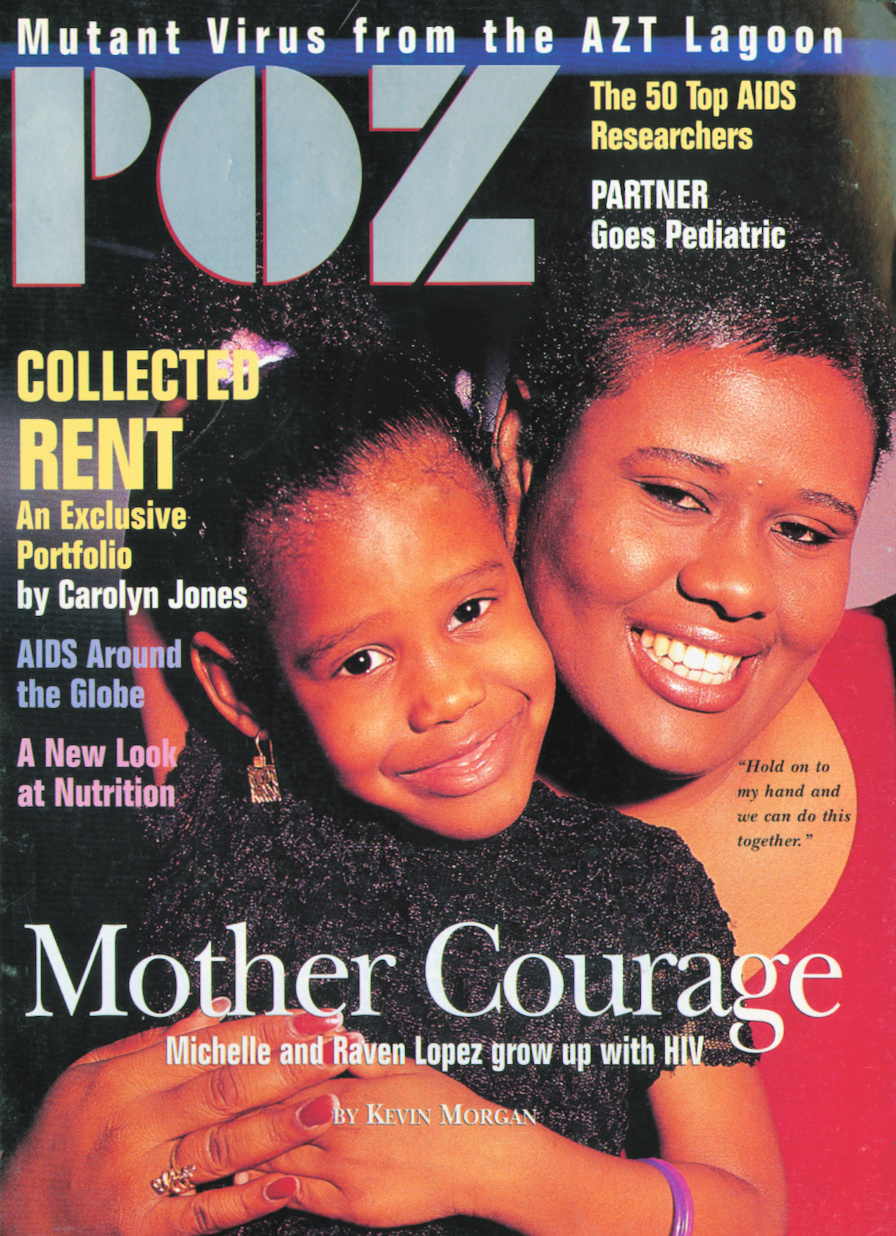

Lopez’s daughter, Raven Lopez, was perinatally infected with HIV. Read more about her here and hear her tell part of her story here. At five years old, Raven appeared on the cover of POZ magazine with her mother (see above) and in this Spin article about the challenges of caring for HIV-positive children. That same year, Lopez enrolled Raven in a pediatric clinical trial that led to the development, and later approval, of the first protease inhibitor drug designed especially for HIV-infected children. Raven followed in her mother’s footsteps, sharing her lifelong journey as a woman of color living with HIV.

Lopez is a member of Caribbean American Pride, a nonprofit community group that promotes HIV awareness and was the first LGBTQ organization to march in Brooklyn’s annual West Indian Day Parade. Caribbean countries currently have the highest incidence rate of reported AIDS cases in the Americas. Learn more about efforts to combat the ongoing epidemic in Trinidad and Tobago in this video.

Today, more than 50 percent of people living with HIV in America are over 50, an average age that keeps rising. In this article, Lopez and other women of color reflect on what it means to live with the virus long term.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History.

AIDS activist Michelle Lopez is a force of nature. The share of trauma and hardship she’s lived through is beyond my imagination. And in describing her life, it’s easy to lapse into cliches about the resilience of the human spirit. Michelle is a survivor—of addiction, attempted suicide, domestic violence, homelessness, HIV/AIDS. But as I realized the first time I heard Michelle speak, she’s a lot more than the sum of her scars. In fact, she’s a riot.

I met Michelle nearly five years ago backstage at the Brooklyn Brewery. We were both featured storytellers at an event hosted by VideoOut, an organization that documents the coming-out stories of LGBTQ people. With her passion and humor and Caribbean lilt, Michelle left her rapt audience in stitches. But her journey had been an arduous one, that much was clear. Also clear was that her 10-minute set barely scratched the surface of the story she had to tell. I made a note to interview her one day to find out more.

Michelle discovered she was HIV-positive in 1990. HIV infection rates and AIDS-related deaths were still on the rise. The advent of the first truly effective treatments was still 6 years off. Almost a decade into the AIDS epidemic, scientists had a much better grasp of how HIV was transmitted, but debunked theories about its spread were hard to stamp out. Fears about contracting the virus through casual contact or saliva persisted. So did the stigmatizing notion that AIDS primarily affected the glibly named “4H club”: homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroin users, and, as an early CDC theory wrongly asserted, Haitians. Women and people of color were barely represented in HIV clinical trials, even while in New York State AIDS had become the leading cause of death among Black women ages 15 to 44.

Michelle was 24 at the time. But a grim statistic she was not. When I sit down with her for our interview she’s 13 days shy of her 55th birthday.

So here’s the scene. It’s the afternoon of Wednesday, February 9, 2022. I’m at CDM Sound Studios on West 45th Street in New York City to record our conversation. On this gray, cold winter’s day Michelle arrives in vibrant head-to-toe pink, her eyes expressive above her matching soft pink mask.

With the threat of Covid still in the air, we take our seats behind microphones in separate soundproof booths. I start by asking Michelle about her childhood.

———

Michelle Lopez: I actually grew up in a wonderful island in the Caribbean called Trinidad. I lived there until I was actually 16.

Eric Marcus: And were your parents from Trinidad as well?

ML: Um, no, my mom, um, my mom is Trinidadian, but my dad is, uh, Venezuelan. So that’s where the “Lopez” comes in, you know. I always tells people I’m the moreno Latina, ’cause that’s what he used to call me, his “little negrita.”

EM: Um, when did you first sense that you were attracted to women?

ML: Oh my goodness, I realized that… Realized it—um, I think accepted it is a difference—but when I realized it, I can tell you I was around at least 13, 14. Yeah, I had—ooh, honey, I had crushes on girls in my high school and I gotta tell you, I was really, I was really—how should I put it—I was, I, I, I wasn’t just exploring. I was, I was carrying it out, you know.

EM: Do you have a memory of a, of a particular crush?

ML: Yes. Oh my god, her name was Allison. Look at me, I’m whispering. I don’t have to whisper anymore! But her name was Allison. Yes. And it was my first kiss that I had with a girl and, oh my gosh, I remember getting in trouble, because I had a teacher… Um, we have locker areas, you know, uh, where we were hanging out in high school and she pulled me in the locker area and, you know, we were there just smooching, you know, we just, we just got right into it.

And I remember my teacher, you know, she came up there and walked right up to us and she looks at me and she said, “Oh, Lopez, this is something new you into now.” So my mother was called. And when I got home, I remember my mom, she said, she said, “I can’t…” She said, “Michelle, I’ve had enough. What the hell do you mean now by kissing a girl?” I said, “Guess what? I kissed her, and I liked it, and I’m gonna do it again, Mommy, you just gonna have to deal with it.”

And she said, “Lord Jesus, it’s true. These goddamn neighbors around here, they throw obeah in my house.” That’s how we use the terminology “voodoo.” “They throw obeah in my house. And you are the one who caught it because these kind of things that you doing, Michelle, is not normal.” Yes, Michelle had boyfriends and girlfriends. Well, I wanted boyfriends and girlfriends, and that’s how my mom dealt with it.

And I could not understand what is the issue, why they don’t understand me. Secretly I was reading, I had gotten my hands on a book by Audre Lorde, and Audre Lorde had this book of poems, Call Me Zami. And it was speaking about the different names, and she had this one poem, and I just saw myself. I just felt I was Miss Zami, you know, and I would get into my own mode, I would get into my own self. And I just, at times I used to be so angry that people did not realize what a fabulous person this was.

———

EM Narration: Michelle’s adolescent defiance led her to act out. If her mother wanted her to date boys instead of girls, she’d show her. She got involved with boys in local gangs, started using drugs, and engaged in increasingly self-destructive behavior. It was more than her mother could handle, and after Michelle made a near-fatal suicide attempt, she was sent to live with her aunt in New York City.

It was 1984. Michelle was 16, an undocumented immigrant, a restless teen. In the years that followed, she bounced around the boroughs, worked as a dancer in New Jersey, hustled for money. It was a precarious existence, but she found community, too.

———

ML: At that time, I was no longer living with my aunt. I made friends, because I was a person that—I would just get on the trains and start riding the trains and start having conversations with people. And I made friends with a group of young people who was hanging out at Tompkins Square Park. That’s where I made friends, and who was gay and who was bisexual and who was whatever we wanted to call ourselves—because I remember a couple of the guys saying you could be whoever you wanna be.

And I remember at 18, um, I got my first girlfriend, I got my first girlfriend hanging out there, and it was a secret because I started then living two lives. Because then I got a boyfriend, and I met this guy one night… We went to this party because we were partygoers and we were all Caribbean young people, and these were girlfriends and, you know, friends of mines that I knew from back in Trinidad.

And I met this Haitian guy and he said to me, “Oh my god, I love you. Something about you is so different.” And I left with him that night and I went and had sex with him that night. And I got pregnant.

I was 19 going on 20. And my son was born January 1, 1987. And it was the first time that I heard about this word called AIDS, ’cause my son’s father was a Haitian young man. And when this baby was born, I heard, it was the doctors and some nurses talking and saying, “We are gonna have to test this one because the baby father, it is written in her notes, he’s Haitian.” And I really did not, no one was communicating with me, but I heard that word.

And by the time my son was two going on three was when I met my daughter’s father. I had my daughter and I was Downtown Brooklyn one day and I ran into these guys that I used to hang with. And one of them said to me, “Yo, you remember that guy that you used to be messing around with when we used to be at the Lower East Side? We heard you had sex with him and, you know, he died from AIDS.” I said, “What?” I said, “Please.” I said, “Y’all full of crap.” I said, “Girls don’t get that. What is wrong with you? Girls don’t get that.”

But I have to say within a month of me having that conversation, I was living with a man who was just supplying me with drugs. And one particular night he beat the shit outta me to the worst I’ve ever been beaten. And I wrapped this baby—I just had my daughter because at that time, um, I gave my mom my son, and she took him to live with them in Trinidad.

And I wrapped the baby that night after being beat up so bad, and I just kept being on the trains, and I was switching trains, and I remember looking up because a bunch of people started coming on the train. And I asked this lady, “Miss, what time it is?” And she said, “Ooh, girl, it’s rush hour.”

And the same time I remember switching my daughter, when I looked up and I saw this ad. I started reading the words, and, Eric, the ad was talking to me. The ad says, “If you’re a woman and you are using drugs and you are dealing with homelessness and if you are an undocumented…” —it was just going down a list of words—“call this number” and you would get help.

I got off the train. I had the coins in my pocket, and I dialed the number and a voice answered. It was not a machine. And after speaking to that person, pouring my heart out, telling them everything that I could have possibly remembered from when I left Trinidad till then, the woman says to me, “Ma’am, where are you right now?”

And I remember looking around in the streets and I said, “It’s Flatbush Avenue and, and, and, and Nevins Street.” And the woman gasped. She was like, [gasp]. She said, “I want you to turn around, turn around east and come straight into Nevins Street. I’m standing at our clinic.” And she gave me the name. It was called at that time Community Family Planning Council.

She said, “We wanna give you an HIV test.” And I said, “Miss, why?” I said, “Why you wanna test me and my baby? We’re females.” And she said, “Honey, I’m so sorry, but women get AIDS, too.” And she said, “Because of the things you told us that’ve been going on with you, if we find out that you have HIV, we could help you.”

And I agreed for them to test me that same day and two weeks later, because we didn’t have the rapid test back then—this was now 1990—and they said to me, “Michelle, you have HIV and your baby is HIV-positive, too.” I was living in a shelter because that same agency placed me in a shelter…

EM: And your baby was diagnosed HIV-positive. What did you think when you heard that?

ML: When it was confirmed—because we were not sure, I kept being told, “but we need to get a confirmation first because she may have an opportunity of shedding your virus”—I mean, I just went into, you know, understanding-learning mode.

And my case manager, she used to take me down to ACT UP floors. And some of those women from ACT UP befriended me and they started teaching me things. And then, you know, there was one particular time, ACT UP women formed this whole group and they had to do, they wanted to do a demonstration down at the Food and Drug Administration because women were not being allowed to participate in clinical trials. And myself and this other woman—her name was Phyllis Sharpe and she had HIV and so was I, and I was a mom who had a positive baby—and I said, “You know, there are things, we need to start…” Michelle was on her way of becoming an activist and didn’t even realize it.

But I was sheltered. I was protected because one of the individuals, a gentleman by the name of Bob Lederer, I remember him, Bob used to say, “Michelle, you cannot do the things on the front line because you’re an immigrant. We don’t want you be in risk of being arrested.” But I was allowed and I was one of the women, I testified before the FDA about why it was wrong, why we were not being allowed to participate in clinical trials. This positive immigrant was part of the team of women who made it possible for women to participate in clinical trials.

I then became, you know, a member of this group called the CCG. You know, the CCG is a community research, you know, group that works with researchers at the AIDS Clinical Trials Group, because then we were fighting, looking for drugs, you know, to help women and children.

And then, my daughter—between her doctor, myself, and me making, making friends and befriending a bunch of researchers from a company called Agouron… My daughter was the kid that was used to identify the dosing for the first protease inhibitors for children. That protease was called Viracept. And because of me being a member of this CCG group and because of the information, I facilitated a fuckin’ meeting with me and a bunch of these researchers. And I said, “Listen, nobody wants to give up a child for you all to get this PK dose.” I said, “I’m gonna give up mine.”

This was actually 1995. She was five years old. She was very sickly at the time. And I said, “Well, what’s she got to lose?” They got a dosage. My daughter made it possible. Protease inhibitors got approved and was being used for adults; there was none for children. Children needed to survive AIDS, too.

When you had a child that was living with HIV back in those days, you had to send them to school with medications. My daughter was taking 42 pills per day. And we had to find a way to get our children to take those meds because the liquid form of it… When we said, “Oh, they can’t do the pills, give them the liquid,” the liquid form, these kids were throwing it up. We wasn’t getting it down. We was not, no. So I decided I’m gonna disclose to her school. And I sent her to school.

And as soon as these teachers learned that this child had the virus, they put my child to sit in the back of the class, open newspaper on the floor. She was not allowed to go on school trips, you know? So by the time she was seven, eight, she knew the kind of level of how the stigma was affecting her.

She started flushing her meds. She didn’t wanna take—she got very sick. She was in the hospital… My daughter one time, the first time she got up and addressed a crowd and spoke as a child born with this virus, she was 11 years old, and she talked about how she was in the hospital within one year 110 times. She counted it as a child how many times she got hospitalized.

EM: And then once she was on protease inhibitors?

ML: Once when my daughter… That protease, what it did for her… She shared it—I remember her on, um, she was on, um, Oprah Winfrey Show, and she said it, “I wanted to eat all the food and I wanted to eat…” ’cause she loved rice and beans. It opened her appetite. She came back to life. She did not get hospitalized that year. Protease inhibitors saved my daughter’s life. It did.

EM: When you started on protease inhibitors, what did it do for you?

ML: Hah! Protease inhibitors—you’re gonna fall out. I got protease breasts. I was a flat-chested girl, and when I started taking protease inhibitors… A bunch of people were developing some of these things called, you know, lipoatrophy and lipodystrophy, you know, a redistribution of fat in our bodies, and my titties grew. It saved my life and I got titties, too.

EM: Wow. So you tested positive for HIV in 1990. You were diagnosed with AIDS in 1996. You had pneumocystis, you had toxoplasmosis, and people in those years, in the early 1990s, died of those things. Did you ever think you were gonna die?

ML: I was not thinking of dying no matter how sick I got back then, because my ultimatum goal, I had to be alive to take care of my children.

EM: When you look back now at this transformation, what do you think?

ML: Eric, the transformation, the turmoils, the agitations, the embarrassment, the shame, the stigmatizing is what have made Michelle who Michelle is today.

I lived. I have a legal status. I’m here. I got involved. I found community. And it was not a community that was looking at me if you’re an immigrant or if you’re Black, you know… It was a community that was teaching people what we needed to do, how to save our lives and to live.

And I’m teaching other gay individuals… Because of me being from the Caribbean, I know the turmoils that we gotta go through. I gotta get back to Trinidad and be able to help my community because the gay people, the heterosexual people, the people who are living with this disease in Trinidad… I can sit up here and talk about “U equals U,” “Undetectable means untransmittable,” and I can talk about my rights. My people in Trinidad don’t have this luxury.

We wanna end AIDS. We can’t just end AIDS—we can’t just end the epidemic in the United States, right? We gotta end the epidemic across the world. And part of my world is Trinidad. Part of my world is Venezuela. Part of my world, you know, is where I’m needed. I have won many a battles and I’m still continuing to win those battles.

EM: And your kids are grown.

ML: My kids are grown. My son is 35. He made me a grandma. I have a wonderful grandson from him. And my daughter, that perinatally infected young woman, is gonna be 31. And she made me, she made me the first grandchild, and that child is negative. So I raised, I got a chance to raise this young woman, take a stand against stigma.

EM: And what do you do to stay healthy?

ML: Ooh, there is quite a list. I love me. The first and foremost that I do today, Eric, is loving Michelle, because I remember when I did not love Michelle. And something that I did not even mention, but it has been a foundation within my life and I’ve, I’m fully embraced, is my spirituality. I’m not religious, I’m not about religion, but my spirituality, look out world. Yeah. Yep. I’m my own driving force.

———

EM Narration: Michelle Lopez continues to tell her story and draw on her experiences to help others. She’s a proud member of Caribbean American Pride, a nonprofit community group that promotes HIV awareness and was the first LGBTQ organization to march in Brooklyn’s annual West Indian Day Parade.

Michelle has also just started a new job as a research assistant and patient coordinator at Brooklyn’s SUNY Downstate Medical Center. In that role, she’ll be teaching people like herself, who are living long lives with HIV, how to manage their care.

They’d do well to pay attention. When it comes to keeping body and soul together, Michelle Lopez knows from experience what it takes.

———

Thank you to Making Gay History’s hardworking crew, including story editor Inge De Taeye, associate producer Ali Lemer, audio engineers Katherine Cook and Cathleen Conte, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Special thanks to our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to Con Edison for their generous support of our education work.

Season ten of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation; the Calamus Foundation; the Kipper Family Foundation; Christopher Street Financial; Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson; Bryan, Christine, and Alex White; Louis Bradbury; and scores of other individual supporters.

Head to makinggayhistory.com where you’ll find all our previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until the next season of Making Gay History.

###