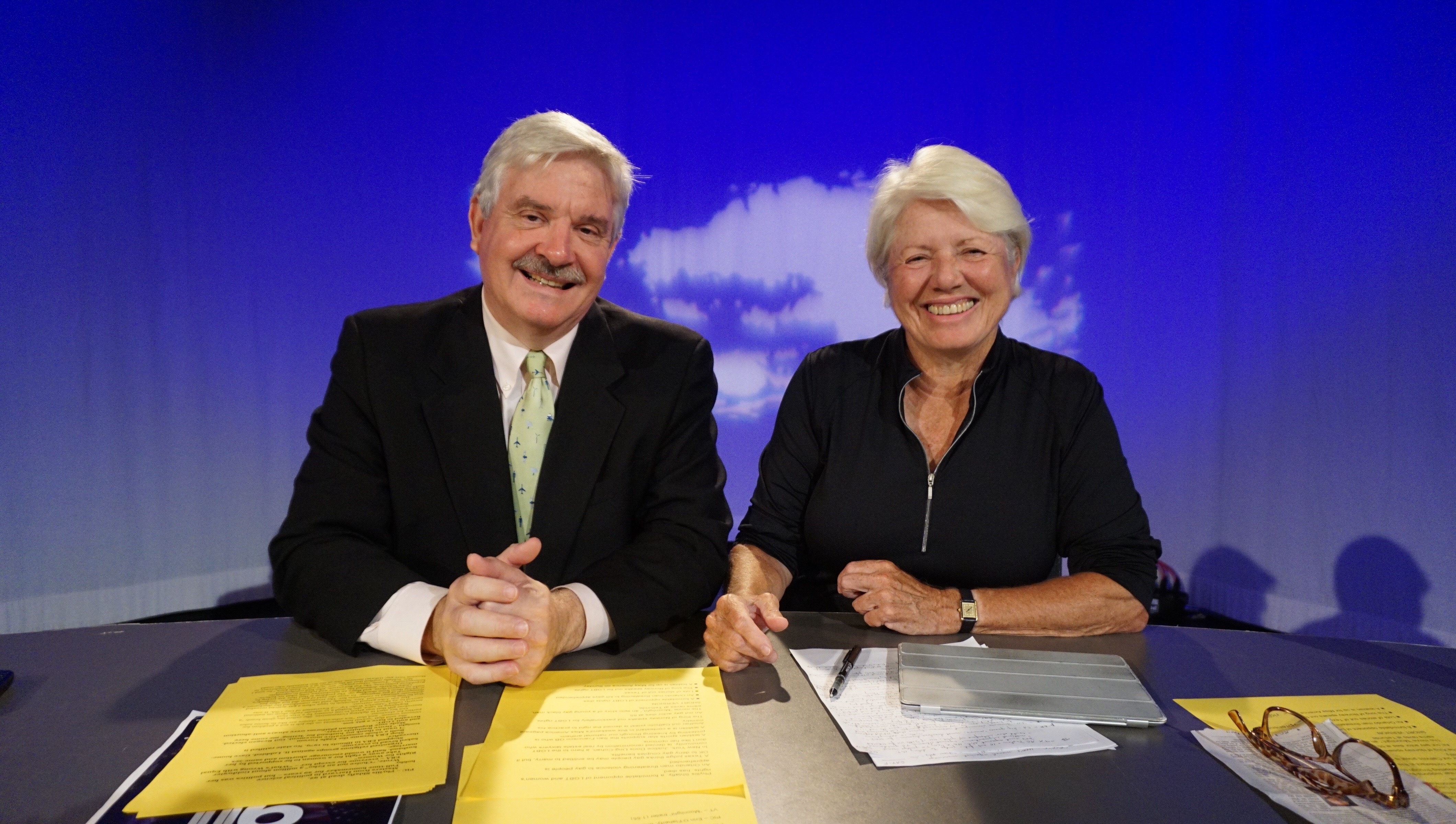

Ann Northrop

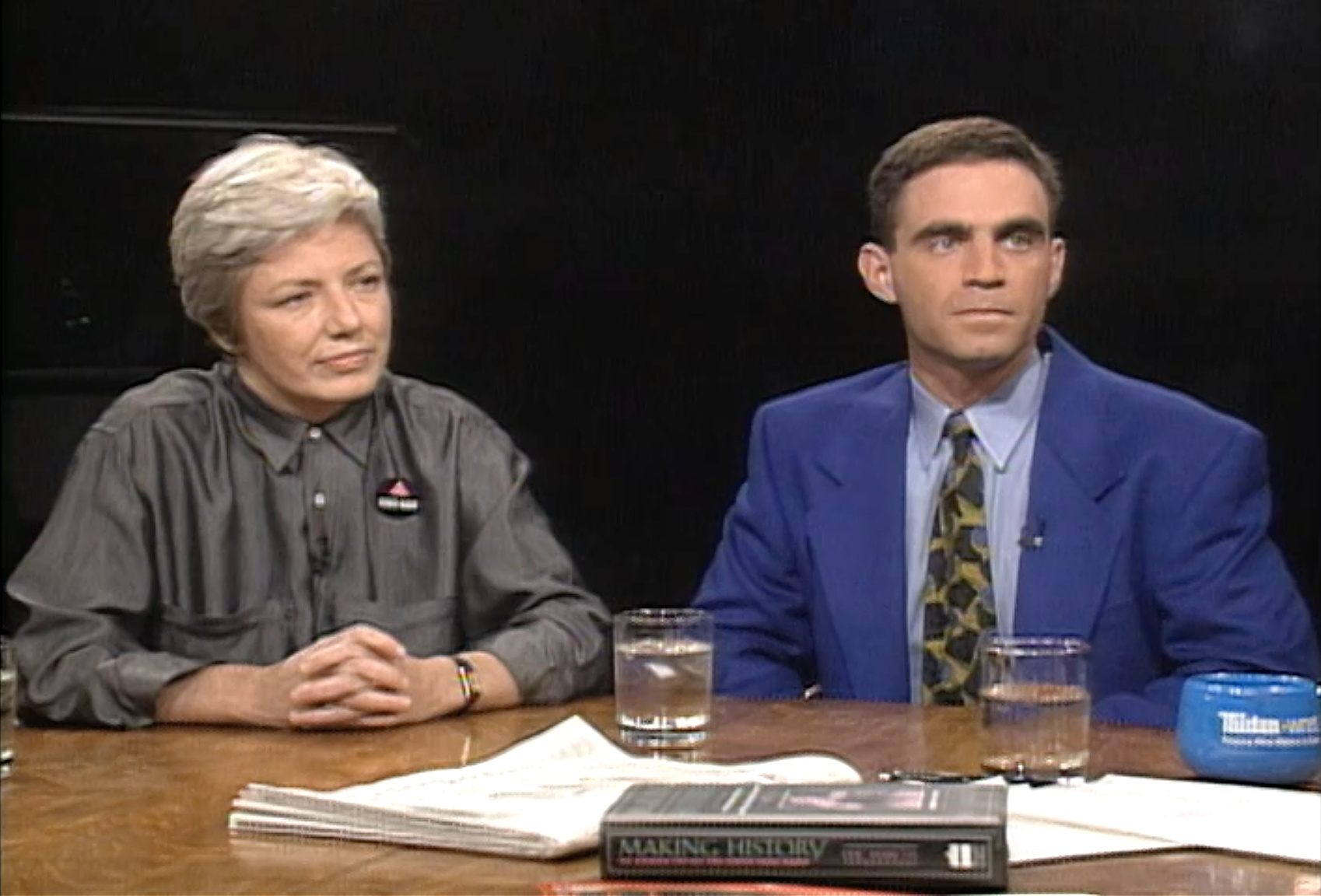

Ann Northrop, circa 1988.

Credit: Milagros Melendez.

Ann Northrop, circa 1988.

Credit: Milagros Melendez.Episode Notes

Fierce and unflappable, veteran journalist Ann Northrop is a natural activist. In this episode, she discusses her most dramatic ACT UP arrest, her work as an AIDS education advocate, her blue-blooded upbringing, and the lure of Angie Dickinson.

———

To learn more about Ann Northrop, read this bio and watch her oral history recorded in 2003 as part of the ACT UP Oral History Project. Northrop’s story was featured in the original edition of the Making Gay History book in a chapter titled “The Radical Debutante.”

After abandoning her career in network television news, Northrop fantasized about becoming a gym teacher—a beloved lesbian stereotype that’s been parodied by lesbian comedians like Rosie O’Donnell and Jane Lynch and satirized for its ubiquity. The butch gym teacher type has found its way into fiction and song, most memorably in lesbian singer Meg Christian’s “Ode to a Gym Teacher” (which is also included in MGH’s Meg Christian episode). In real life, lesbian gym teachers may find their livelihood threatened because of their sexual orientation, a predicament explored in depth in this 1990 dissertation.

At the suggestion of Joyce Hunter at the Harvey Milk High School, Northrop became an AIDS education advocate at the Hetrick-Martin Institute (now known as HMI and originally known as the Institute for the Protection of Lesbian and Gay Youth). Learn more about Hunter in this MGH episode; on that same webpage, you’ll find additional information about HMI and the Harvey Milk High School, which was established by the institute in 1985. Learn even more about HMI in our episode featuring cofounder Damien Martin and the accompanying episode notes here.

Northrop was introduced to Hunter by Vivian Shapiro, a prominent activist in the lesbian community and a friend of Northrop’s. Shapiro was also a founding member of ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power, which was formed on March 10, 1987, at New York City’s Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center (now the LGBT Community Center). Their first demonstration, a protest against the pharmaceutical industry’s profiteering from the AIDS crisis, took place on Wall Street that same month.

Northrop joined ACT UP shortly before their second protest on Wall Street a year later, which got considerable mainstream media coverage. Northrop was arrested at the demonstration—her first but by no means last arrest—so the ACT UP civil disobedience training she’d received stood her in good stead. A forceful public speaker, Northrop was often called upon to address the press on ACT UP’s behalf; for example, watch her at the 7:20 mark in this footage of the 1989 Target City Hall action. She also appeared with fellow ACT UP members in this 1990 episode of the Phil Donahue Show.

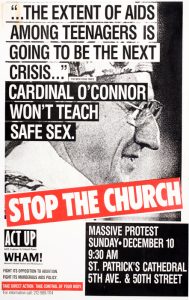

As Northrop relates in the episode, on December 10, 1989, she was arrested during ACT UP’s controversial Stop The Church protest at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. To learn more about the demonstration, read this article or watch this scene from the documentary United in Anger: A History of ACT UP.

For an in-depth overview of ACT UP’s early history, have a look at Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993, and explore the ACT UP Oral History Project, an archive of 187 interviews with members of ACT UP.

As both an activist and journalist, Northrop has been a prominent LGBTQ rights advocate for decades. Watch her alongside Eric Marcus in this 1992 episode of Charlie Rose, or have a look at her semi-regular segment “Ann Northrop Mouths Off” on Dyke TV (try the first episode at the 11:45 mark).

In 1996 Northrop joined longtime activist Andy Humm as cohost of the weekly news program GAY USA. You can watch episodes from the past few years here. Episodes from 2000 to 2012 are available through NYU’s Fales Library & Special Collections in the Gay USA Collection. Pre-2001 episodes can be found in the Gay Cable Network Archives.

Northrop’s most recent activism includes work with the Reclaim Pride Coalition, which since 2019 organizes New York City’s Queer Liberation March, an all-volunteer people’s march in the spirit of the original 1970 Christopher Street Liberation Day March. Hear Northrop explain its significance here and in this MGH episode about the legacy of Stonewall.

Northrop has also been active in Gays Against Guns, which describes itself as “an inclusive direct action group of LGBTQ people and their allies committed to nonviolently breaking the gun industry’s chain of death—investors, manufacturers, the NRA and politicians who block safer gun laws.” The organization was formed shortly after the June 12, 2016, mass shooting at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, that left 49 people dead.

In the episode, Northrop mentions harboring a crush on actress Angie Dickinson. Take a moment to immerse yourself in the screen legend’s charms: learn about her life and work in this short video, peruse these glamor photos, watch her discuss her career, and eat her delicious honeymoon sandwiches.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus: Were you arrested?

Ann Northrop: Yes.

EM: Ann!

AN: That was my first arrest ever in my life.

EM: Boston debutante arrested.

AN: Yeah, yeah. The best thing was that one of the things we’d been told at, uh, civil disobedience training was to, uh, be prepared for this kind of long time in jail. And so I had followed instructions and brought two peanut butter sandwiches and a book to read. And they let me keep them.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History.

Activists are made, not born. But the Ann Northrop I’ve known for the past three and a half decades is such a natural, I can almost imagine that she entered the world clutching a baby bullhorn. Ann was a confident, high-achieving kid from the start, with an innate gift for leadership. Loud—but out and proud, that came later. As fierce and fearless as Ann appeared even then, she kept her sexuality a secret.

I don’t remember how Ann and I first met, but it seems inevitable that our paths would cross. Without knowing it, I’d been following in Ann’s footsteps for years. I attended Vassar College a decade after she did. And at different times we both worked at ABC’s Good Morning America and CBS Morning News, where Ann eventually rose to become a coordinating producer.

But by the time I interviewed Ann for my Making Gay History book, she’d left her enviable career in network TV news and was working for the Institute for the Protection of Lesbian and Gay Youth—a small nonprofit later renamed the Hetrick-Martin Institute in honor of its founders.

So here’s the scene. It’s late autumn 1988. Ann and I have arranged to talk at my apartment on 69th Street and Broadway in New York City. I’ve only recently started conducting interviews, and I’m still getting the hang of my new tape recorder, so the quality of the tape you’ll hear is a bit uneven. But I manage to get Ann miked up and press record.

We dive right in—not with the official interview but with some good old-fashioned workplace gossip about our experiences at ABC and CBS and our former colleagues. Until we finally get down to business…

———

EM: Interview with Ann Northrop, Saturday, December 10, 1988. Location is the New York City home of the author. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

AN: Hi, Eric.

EM: Hi, Ann. Uh, let’s, let’s go back a bit. When did you first get involved in any, any aspect of, of gay rights, uh, the gay rights movement?

AN: I would probably have to say not until after I came out to some extent, which was late. I came out when I was 28 in 1976 when I first got involved with my lover. Uh, I did not feel comfortable talking to another soul in the entire world about my homosexuality until I had a lover and felt there was one other person who cared enough about me not to hate me for who I was. I was very scared. I was very conservative. I hid all my life until that point.

All through my teenage years I tried to say, these feelings will go away, they’re not real, because I’m not one of these awful people. I can’t be one of these weirdos, these Martians, these, uh, horrible, disgusting, uh, perverts. That’s not me. I’m a nice, uh, you know, upper-middle-class blue-blooded WASP.

EM: Where did you get that, that image? That image must have come from somewhere.

AN: Yes. Well, I think that is the pervasive image of gay people in this country, or has been. It certainly was when I was growing up, or in the community I grew up in. You know, limp-wristed men, uh, known as fairies. Uh, women who looked like truck drivers and were known as bull dykes and wore motorcycle boots or whatever, and were, uh, unattractive, disgusting people.

So I hid throughout my teenage years. I dated boys. Uh, I sometimes say I’ve dated half the men in the world twice, including people like Pete Coors, now the, uh, president of Coors beer.

EM: You are kidding.

AN: Shall we make public that Pete Coors dated a lesbian? This amuses me. And I continued to date men in college, uh, less and less frequently, more and more feeling that I wasn’t enjoying it. But at the same time, I also realized my feelings for women and was becoming more in touch with them. But I still could not identify with the stereotypical images and felt that I would never, ever be able to have a relationship with any of the women I was actually attracted to, because they were all “straight,” quote, unquote. For me, the equation was, if I identify myself as a lesbian, what that meant to me was that I was accepting being alone for the rest of my life.

EM: I wanna jump to when you went to work for CBS. Is there anything during that period—between, let’s say, when you were 20 and 28—is there anything in terms…? You were in the closet during that whole period.

AN: I was in the closet, uh, until 1976. When I was hired at Good Morning America—this was 1981 that I worked there—I was completely out. I was very fresh in my relationship at that point, or still feeling it, and very, uh, getting more aggressive about being out. It was one of those periods where, you know, you just wanna go out and tell the entire world.

I was extremely flagrant, uh, in ways that I am a little embarrassed about now. I remember one specific staff party, and, uh, I took my lover. Spouses came to the party. It was basically a writers’ party. And we were necking, uh, in the living room, with a lot of other people around. And, uh, being very affectionate. And people were not comfortable with that. And I know that there were a lot of, uh, mean remarks behind my back, uh, several of which were reported to me.

EM: So this party caused you lots of misery.

AN: Well, yeah, I think it really made people angry. And I think if I had been, uh, cooler and, uh, less, uh, aggressive in my behavior, I probably would have had a somewhat easier time at GMA.

Uh, and in fact, by the time I got to CBS, I had gotten a lot of that out of my system, and I think I had a very successful and happy time at CBS with my colleagues.

One of the lovely things at CBS was that… Because I had a picture of Angie Dickinson on my telephone and because I would talk about her aggressively as just someone I found enormously attractive and because I would refer to the fact that I was attracted to older sleazy blondes, of which she was the epitome, there came a day when, uh, she in fact was booked by Pat Collins in the entertainment unit for a post tape. And when that became public knowledge, virtually everyone on the entire staff called me up or came running to my office to say, “Ann, Ann, guess who’s coming? Angie!” And they were so excited for me. They were truly happy for me that I was going to have the experience of being able to play with this, uh, uh, you know, movie star crush. And I felt that I was absolutely treated in the same way that any heterosexual crush like that would have been treated. And they did… I escorted her around the building for a couple of hours, and I got to chat her up and had a great time and, uh, loved her even more after spending time with her because she was fully as wonderful and humorous as I thought she would be.

EM: When you left, when you decided to leave CBS, you had status, …

AN: Yes.

EM: … you had power, you worked for the network, for god’s sake… You threw it all out the window to work for an underfunded, overworked institute that works for the delivery of social services to gay and lesbian youth and, uh, does education work.

AN: Right.

EM: Why did you do it?

AN: Several reasons. Uh, most fundamentally, I was not happy. So I thought about what it was that would make me happy, and realized that what I really liked about, uh, television and about CBS was teaching people things, conveying values, getting my point of view across.

And then I thought, aha, maybe the line I’ve been saying as a joke for years is true. And the line was, when people would say, “Well, what do you really want to do when you grow up?” I would say, “Well, what I really want is to be a gym teacher, but I’m afraid of fulfilling the stereotype.” And I said, you know what? It’s absolutely true.

EM: That you’d always wanted to be a gym teacher, a high school gym teacher.

AN: That I really had, I really always had. Uh, that I’d enjoyed team sports more than almost anything in my life, having been brought up in a nice New England, uh, blue-blood household, being the former debutante that I am. And I am a Boston debutante. Uh…

EM: Did you have a coming out, at 16?

AN: Uh, a little later. Uh, I was not living in Boston at the time. We had moved to Denver, where I attended high school, but I attended the, uh, Boston debutante cotillion as a debutante.

Uh, at any rate, um, I said to myself, yes, you really, really do love team sports and doing all that. And you really are terrified of being identified as the little butch, uh, gym teacher.

EM: You were already in your thirties by then.

AN: Oh, uh, this was two years ago! A year and a half ago. At any rate, I decided I wanted to teach. No more beating my head against the wall. I was going to teach field hockey in a private girls’ school. And, uh, I would teach elite, smart-alecky girls just like me. And I would probably divide my time between team sports and maybe a little nineteenth century English literature on the side. A little field hockey, a little Jane Austen.

In the midst of, uh, exploring this, I had lunch one day with a friend of mine, Vivian Shapiro, a lesbian who has some prominence in the current movement. And she said, “Well, what about the Harvey Milk High School? How about that as a place to teach?” And I thought, perfect, what a great idea. She said, “Call my friend Joyce Hunter.” I said, “Fine.”

I called Joyce. I went down to see her at the institute, which was then on East 23rd Street. And, uh, sat down with her and described—showed her my resume, which knocked her out. She sort of, you know, what are you doing here?

EM: Right.

AN: And I described my little teaching dream. And by that time thinking, adjusting my thinking to the Harvey Milk School, I thought, oh, okay, what I’ll do is, I’ll—I had grandiose dreams—I said to myself, I’ll take, uh, all these, uh, gay boys and I’ll make them into the city champ softball team and it will destroy all the stereotypes of gay boys. And this will be my great accomplishment.

So I described all this Joyce and she just got hysterical and thought I was the funniest thing that had ever walked in the door. Because, as she explained to me, the Harvey Milk High School was not some great Gothic structure with hundreds of kids, but was in fact one room in the back, and that was the Harvey Milk High School. And they certainly didn’t have a gym or anything approaching a sports program.

EM: So Joyce was a little surprised, she…

AN: Joyce was amazed. Joyce was hysterical. But she then said to me, “No, the Harvey Milk High School is not appropriate for you, that’s not, forget that.” She was very dismissive, very quickly, but said, “But we have a contract from the City Department of Health to do advocacy of AIDS education, to go around and talk to community groups, parents groups, Board of Ed, whatever, to advocate for AIDS education. Not to do actual AIDS education, but just to be advocates for AIDS education. And would you be interested in that?” And I said, “You want to pay me cash money to do public speaking? Me, the big ham?” And she said, “Yes.” And I said, “Where do I sign up?” It just sounded to me like the greatest idea in the whole world.

And the most ironic thing of all to me is that what I’ve found I enjoy most is not the speaking to community groups or to boards of ed or parents, but, as it turns out, I am doing direct AIDS education to kids and that is the most fun of all. Dealing directly with kids. And the most exciting experience I had with that was, uh, one day last year at—or earlier this year—at a Daytop Village drug rehab facility in Brooklyn. I was asked to go in and do AIDS education to an alternate high school population there, about 20 kids.

I sat down in a circle with them. I started talking about AIDS. We talked for a little while. One kid sitting next to me said, “Well, you know, the way to get rid of AIDS is to, uh, kill all the queers.” And this was the first time I’d had something like that happen, and I turned to him and said, uh, “It’s interesting you should say that because I’m one of those queers, and I’m certainly not crazy about your language, and that’s not the answer, but let’s talk about that.” And everybody’s jaw dropped to the ground. And we proceeded to have a two and a half hour nonstop conversation, me and these kids, who were basically self-identified fag-bashers. Certainly that kid was.

Two and a half hours nonstop. Kids do not sit and talk to grownups for two and a half hours nonstop. And it was one of the most exciting experiences I’ve ever had.

EM: Why was it exciting?

AN: Because I could talk honestly about my life. Because I could exchange information with them that they were obviously so… It was like they were in the middle of the Mojave Desert and someone offered them a canteen of water. They were so thirsty for this information, for this conversation.

I had not been hired to go talk about homosexuality to people. But that experience made me understand how important and valuable it was, because I go in with what in fact is a radically different point of view, which is my own normalcy. Don’t tolerate me as different. Accept me as part of the spectrum of normalcy. Uh, and that turns out to be a, a radical point of view, but one that is very exciting to most people.

———

EM Narration: One year to the day after my sit-down interview with Ann—on December 10, 1989—Ann participated in a controversial protest at New York City’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral called Stop the Church.

It was organized by ACT UP—the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power—a direct action and advocacy group founded to save the lives of people infected with HIV in the face of overwhelming indifference and neglect from the government, the medical establishment, and society at large.

Ann had joined the group the previous year and was among the scores of protesters arrested at the demonstration. It was a huge story at the time. So on January 6, 1991, on the eve of Ann’s sentencing, I gave her a call to ask her about the experience.

———

EM: Why was St. Pat’s significant? Why was going up against the church significant?

AN: Because the archdiocese in New York does everything it can do to interfere with instruction about safe sex. Tries to, uh, stop the curr—the AIDS education curriculum. Is currently trying to stop, uh, any availability of condoms in schools. And because the cardinal was standing up and lying about HIV. He was telling people that monogamy would protect them from infection, uh, and that condoms didn’t work. And those were both major lies, as far as I was concerned, that were going to kill people.

EM: Was this a day when the cardinal was in the church?

AN: Oh, yeah, absolutely.

EM: This was a Sunday.

AN: Yeah, the 10:15 mass. The, uh, major mass every Sunday. It was this whole big deal. There were 5,000 demonstrators outside. The place was chaos outside in the streets. There had been a lot of publicity leading up to this. People were amazed at the turnout, but it was such an appealing target. People are so angry at Cardinal O’Connor and the archdiocese here, uh, that people just came out in droves even though it was about five degrees out and, and bitter, bitter cold.

Forty or 50 of us, uh, drifted into the church, trying to get there early to make sure that we could get seats and everything. But then they cleared the church for one of only very few times in history. Uh, filled it with cops. Took bomb-sniffing dogs inside. Made us wait outside while they, uh, searched everything. Then they opened up the doors and let us in again.

The entire local and network press are in there. Uh, the mayor is in there—Koch went in to defend the cardinal. Uh, the police commissioner was there to defend the cardinal. Now, meanwhile, mind you, there are maybe three dozen of us who plan to do anything, and no one plans to do anything more than just read a statement.

So now there are hundreds of cops, the mayor, the police commissioner, bomb-sniffing dogs, uh, several hundred, uh, seminarians who had been brought in as decoration for the front area. Um, undercover cops as, uh, ushers everywhere. And the place is quite tense. And the Cardinal is standing up and mumbling and making pronouncements about the coming disruption.

So the sermon started. We started doing our prearranged thing. The cops started swarming all over the cathedral…

EM: What were your prearranged things?

AN: Me and others lying down in the middle aisle, maybe, uh, maybe 25 or 30 of us in the middle aisle. Uh, several clumps of people in various parts of the cathedral starting to read a statement aloud. A few people handcuffing themselves to pews. Uh, not saying anything, just sitting there handcuffed to pews. Uh, but meanw—and then one or two people who, uh, as the cops were running around and blowing whistles and swarming around and the parishioners were, uh, trying to drown every—out the statements with loud singing and everything, uh, a couple of people, uh, started yelling. So the whole place got a little chaotic. Uh, and the police just arrested us, uh, one by one, and carried us out of the cathedral on, uh, stretchers, big orange stretchers they brought in.

EM: So you were carried out.

AN: I was. I was the last one carried out. And when I was carried out, um, everyone else had been taken out before me. The place was very quiet. Uh, some praying, some hymn singing. And as I was lifted up on my, uh, stretcher—and I had been silent throughout, throughout the entire time I was lying on the floor—but when I was picked up and was being carried out on the stretcher, uh, during a moment of silence during that, you know, transition from one part to another, I yelled, in a sort of resounding voice through the cathedral, “We’re fighting for your lives, too. We’re fighting for your lives, too.” And, and repeated that half a dozen times as I was carried out of the cathedral.

EM: My god, who could have written a scene more potent?

AN: Fantastic. Who plays this in the movie version is our next question.

EM: Angie Dickinson.

AN: No, Elizabeth Taylor…

EM: Oh, god.

AN: … plays me, and has Angie posters all over her room.

EM: Right.

———

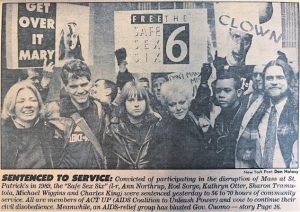

EM Narration: The day after our call, Ann was found guilty on all the counts she faced—disorderly conduct, disruption of a church service, trespass, and resisting arrest—charges that Ann in a recent email dismissed as “nonsense.” She and her fellow arrestees were sentenced to 10 days of community service, a lighter sentence than they’d anticipated. At the hearing, the judge acknowledged that the protestors had engaged in civil disobedience for honorable reasons—but, she said, “Even Gandhi and Martin Luther King had to pay a price for civil disobedience.”

By the time Ann left the Manhattan Criminal Courthouse, the national press had gathered on the front steps of the building. Ann stepped up to the bank of microphones and declared, “The judge compared us to Gandhi and Martin Luther King!” It was a Northrop master class in righteous spin.

Ann’s Stop the Church arrest was not her first and not her last. And ACT UP New York is just one of the activist groups Ann has dedicated herself to over the decades. In addition to fighting to end the AIDS crisis, she’s spoken out for LGBTQ equal rights and against gun violence and police oppression. And she’s called attention to the many injustices that exist at the intersections of gender, race, and class.

In the mid-1990s, Ann returned to her roots in journalism and since then she’s co-hosted the weekly national cable TV show Gay USA together with Andy Humm, another legendary activist. And in 2018, at the age of 70, Ann became a founding organizer of the Reclaim Pride Coalition, which now hosts the annual New York City Queer Liberation March, a return to the activist, democratic—and non-corporate—spirit of the first Pride marches.

Ann Northrop remains a role model for new generations of activists who are building on the movement that people like her helped to create. I’m proud to call her my friend.

———

Many thanks to our dedicated Making Gay History crew, including story editor Inge De Taeye, associate producer Ali Lemer, audio engineer Cathleen Conte, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Special thanks to our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division for their assistance. And thank you to Con Edison for their generous support of our education work.

Season ten of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation; the Calamus Foundation; the Kipper Family Foundation; Christopher Street Financial; Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson; Bryan, Christine, and Alex White; Louis Bradbury; and scores of other individual supporters.

Head to makinggayhistory.com where you’ll find all our previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

And to keep up with what we’re doing, sign up for our newsletter on our website, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. And please keep those 5-star iTunes ratings coming so more people can discover our proud history through the voices of the people who lived it.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

———

EM: Um, let me ask you some follow-ups. Uh, regrets?

AN: Uh, not having been able to date women in high school.

EM: So your only… So, so paraphrase: your only regret is not, not having dated girls in high school.

AN: Right.

EM: That’s, uh, that may be the end of your interview.

AN: That’s fine.

###