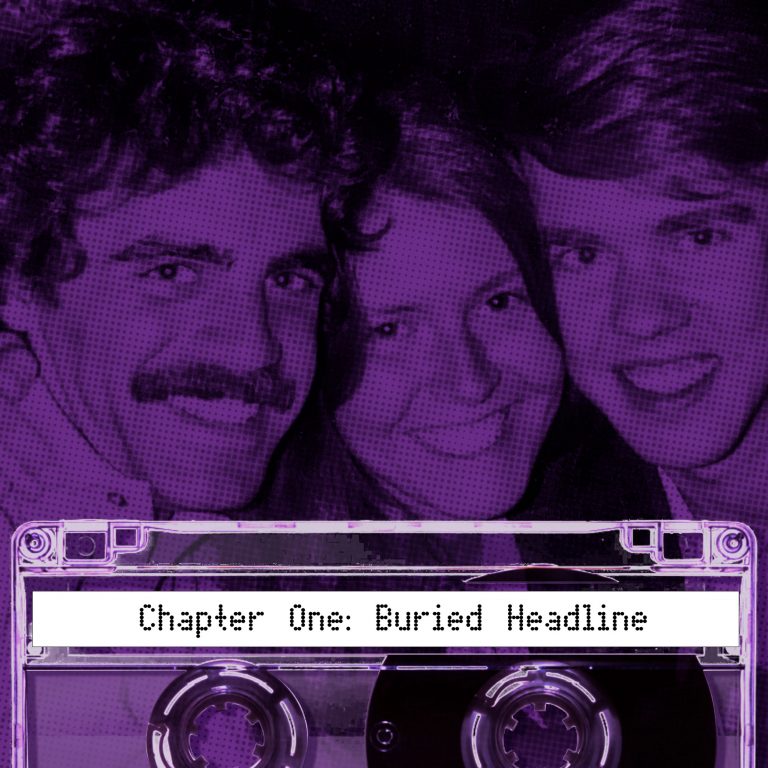

Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis — Chapter 1

Episode Notes

“Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” said the New York Times headline on July 3, 1981. It was the first time Eric Marcus read about what came to be known as AIDS. Nothing for me to worry about, he decided, and turned the page.

———

For a comprehensive overview and useful links related to HIV and AIDS, consult this HIV.gov timeline.

For a New York City-specific timeline, see this New York magazine article. (Please note, however, that the Patient Zero theory referenced at the top has since been discredited; for more information on the subject, watch the documentary Killing Patient Zero.)

This chapter covers July 1981 to the spring of 1982. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), by the end of 1981 there were 289 reported cases in the United States of what would later be known as AIDS. There had been 233 deaths. In the first half of 1982, 329 more cases and 211 more deaths were added to that total. Because there was no test for HIV at the time, the actual numbers are unknown.

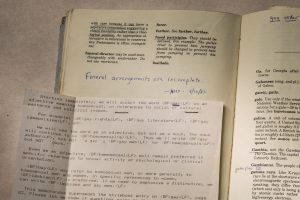

The buried headline referenced in the episode’s title—“Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals”—appeared on page A20 of the New York Times on July 3, 1981 (see below). The Times had been given an advance copy of the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), which detailed the emerging epidemic. The first MMWR to report on the new disease had been published a month prior, mentioning five gay men in Los Angeles who had been diagnosed with pneumocystis carinii pneumonia.

NYT article PDFLearn more about early media reporting on AIDS in this article. The first story about AIDS in a U.S. publication appeared in the New York Native, a gay newspaper, on May 18, 1981. Read the article and a 2021 interview with the author, Dr. Lawrence Mass, here.

The July 3 New York Times article used the word “homosexual” as a matter of policy; the paper did not start using “gay” to describe gay people or the gay community until 1987. Read about the policy change in this David Dunlap article. For more on the history of the term “homosexual,” read “The Decline and Fall of the ‘H’ Word.”

New York Times/Redux Pictures.

Before AIDS, the skin cancer Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) was virtually unknown to the general public. In December 1981, nurse Bobbi Campbell wrote about his KS diagnosis in his piece “I Will Survive!” in the San Francisco Sentinel. Campbell declared himself the “KS Poster Boy” and dedicated himself to educating the community. Listen to Campbell in this in-depth January 1982 interview on the radio show The Gay Life (segment starts at 31:15). In June 1982, Campbell was featured in this CBS News segment. For many Americans tuning in, it was the first time they had seen a gay man stricken with the mysterious illness.

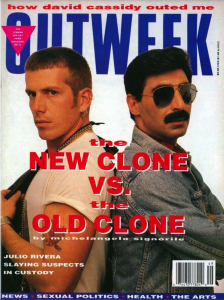

In the episode, Eric uses the slang term “Chelsea clone” to describe his date Bob. The original gay “clones” of the late 1970s adopted a hypermasculine style with tight Levi’s 501 jeans and mustaches, and were variously known as “Christopher Street clones” (after the street in New York’s Greenwich Village, which was a popular gathering place for gay men) and “Castro clones” (after the Castro District in San Francisco). The aroma of amyl nitrate hangs around the very word. The “Chelsea clone” iteration, named after New York’s Chelsea neighborhood, reflected the evolution of a social scene, changes in fashion, and the growing number of gay men who lived there (see below). The term was often used disparagingly.

Clone looks in their various forms are both remembered nostalgically for their iconic imagery and criticized for a conformist masculinity that excluded other gender expressions. Read about the evolution of clones in this November 1990 issue of Outweek (starting on page 39). Firmly rooted in New York’s collective gay psyche, mustaches are always threatening a comeback.

Gay men began migrating from the western part of Greenwich Village to Chelsea beginning in the 1960s, leading a wave of gentrification through the 1970s and ’80s of that one-time down-at-the heels neighborhood. But the streets could be dangerous for them. Read about how gay men banded together to protect themselves in “Early Gay Activism in Chelsea: Building a Queer Neighborhood” by Michael Shernoff.

Hell’s Kitchen, located about a mile north of Chelsea, was not a thriving gay enclave when Eric lived there with his friend Doug in the summer of 1981, but it became a popular neighborhood for gay men years later.

In the episode, Eric and Doug reminisce about playing the cast album from the 1947 Broadway show Brigadoon. Watch the trailer for the 1954 film adaptation here. Or just listen to “Almost Like Being in Love,” indisputably the show’s best song (at least according to Eric).

And, yes, you can boil your jeans to shrink them.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is a first for me, and something different for this podcast. After eight seasons of bringing you the stories of the LGBTQ civil rights movement through the voices of the people who lived it, eight seasons of bringing you other people’s stories, for the next six episodes, I’m going to share a part of my story.

Exactly 40 years ago, news first broke into the mainstream of a deadly new disease, a disease that’s come to infect tens of millions of people around the world. I was coming of age and coming out during those first terrifying and confusing years of the AIDS crisis as my friends and neighbors fell ill and died. Those were years that I’ve tried hard not to remember. They’re also years I can’t forget.

Sometimes history is hiding in plain sight.

After decades of mining other people’s oral histories, I’m digging into my own. I’m returning to memories from 1981 to 1988, trying to reconstruct what happened. Because it turns out it’s part of our LGBTQ history and because ultimately it’s the story behind Making Gay History, and how and why it came about. So, yes, this season of Making Gay History is different. It’s an audio memoir, my own oral history. Remembering some of those we lost, and conversations with people who went through it with me.

This is chapter one: “Buried Headline.”

———

Jed Mattes: It was the first notice that we had of a rare cancer seen among male homosexuals.

Randy Shilts: It wasn’t called AIDS then. It was called GRID.

Damien Martin: A group of men with Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Larry Kramer: “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.”

Vito Russo: We were told that Nick died of cat scratch fever, which does not kill you, you know—it was just not possible.

Enno Poersch: He died of AIDS before they knew what AIDS was, you know, when they were all still running around and going, “We don’t understand what this is all about.” He got sick in, uh, ’80 and he died January 15 of ’81.

Vito Russo: We didn’t know then that this was AIDS, but it was AIDS.

Larry Kramer: Even when we found out in ’81, it was much bigger than we thought.

Randy Shilts: I felt so strongly that that would have been a page one story if it had been anybody else getting it.

Larry Kramer: When I saw that in the New York Times, I was scared.

Eric Marcus: Well, if the Times covers it, it has to be real.

———

EM Narration: It’s July 3, 1981, and I’m reading the New York Times over breakfast—Cheerios and low-fat milk, sliced banana. Doug is still asleep. He’s my best friend from college, not an early riser. We’re renting a tiny apartment for the summer in Hell’s Kitchen, a few blocks west of Manhattan’s Theater District. I’d say the neighborhood is rough around the edges, but it isn’t just the edges.

Page 20 of the paper, a thin single-column story running down the left-hand side catches my eye. At the top, two lines, bold type: “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” A shiver runs up my spine. To me, we’re gay men, but the editors of the New York Times are still insisting in 1981 that we can only be referred to as “homosexuals.” Some say, “homo-sexuals.”

Forty-one homosexuals and an often rapidly fatal form of cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma. It’s only usually seen in elderly men of Mediterranean descent and children and young adults in a belt across equatorial Africa. The purplish lesions would become unmistakable—all too familiar—in the years that followed. But in July 1981, I’d never heard of it. The men in the article range in age from 26 to 51. I read on. The cases involve men who’ve had “multiple and frequent sexual encounters with different partners.” As many as 10 sexual encounters each night, up to four times a week. None of the patients knew each other.

I’m 22, a wannabe preppy. Maybe I’ve had 20 sexual partners in my life. It’s not nothing, but it’s not 40 a week. The article was in lockstep with my own prejudices back then about gay men who lived life in the fast lane—or at least a much faster lane than the one I lived in. My internalized homophobia heard the message loud and clear. What did these guys expect? Maybe they even deserved it.

Of course I realize now how awful it was for me to feel that way, but it’s how I felt at the time, not knowing nearly enough about what was happening and what was to come. In that moment at the kitchen table, thinking that these 41 unnamed homosexuals weren’t like me, despite how sexually active I’d been myself, does the trick. The chill works its way back down my spine, and I turn the page.

My recollection of the article is clear enough, but I’m trying to remember more about the context. So I’m calling Doug, my Hell’s Kitchen roommate.

———

EM: Doog! There you are!

———

EM Narration: Doug and I became friends our first year at Vassar College. And even now in our 60s, I call him “Doog” and he calls me “Ericles.” It’s embarrassing, but it’s true.

———

EM: It’s so nice to see you, Doog. Yes, no, no, don’t behave, but press the button.

Doug Aucoin: Alright, I am holding it to my ear and I’m talking as quietly as I can.

EM: I’m trying to sort through my memories from the summer of 1981.

DA: Mm-hmm.

EM: How did we wind up taking an apartment on 44th and Ninth Avenue? Were you trying to get away from your mom, and I was trying to get away from my mom?

DA: Yes. Basically, after college I think we both had to move back to our mothers’ homes because of course we had no money. I think at that point I had a job then, and I think you were doing the walking tours—is that right?

EM: Yeah, I had started my, my, my ultimately failed walking tour company, and I was flying to Nova Scotia every Sunday for Tauck Tours.

DA: That’s right. I remember that now.

EM: Doug, um, describe me to me from that summer. What was, what was—I’m sure I haven’t changed at all in, in 40 years—but, but, um, what was your memory of me? Because I have memories of you with the hair, hairband and doing, you know, your ablutions in the morning…

DA: Hairba—oh, was I, did, oh, to get my hair out of the way—right! Not only did I have to deal with my huge mane of hair and blow-drying, and I was very big on creams and all that stuff, right? I also had contact lenses. So the whole thing was a long project.

So, um, I don’t remember anything in terms of your habits. I just, I’m sure that you were an earlier person than I was, and that you were, um, faster in the bathroom. I’m sure both those things.

EM: What was I like as a person then?

DA: I’m supposed to be honest here?

EM: Yes, absolutely honest.

DA: Well, you were, you were still kind of in your, in your mode of just, like, kind of, like, wanting to use men, you know, and not really commit to long-term relationships, but just to, to hook up whenever guy—always looking for the next Mr. Cute Guy, that was what you were kind of doing.

EM: Really? Because I r—I was thinking that I didn’t, that I didn’t sleep with anyone that summer except, except you.

DA: Oh my god. I, I was thinking that, too, actually. I was thinking that even during that summer, I realized, even though I was, like, free for the first time, I don’t think that either of, I don’t think either of us did. I know we never, like, brought people home or anything like that.

EM: No, no.

DA: I’m sure we didn’t. But, no, I was never into that kind of thing, but…

———

EM Narration: My memory of that summer includes listening over and over again to a recording of Brigadoon, an incredibly romantic falling-in-love Broadway show. And I remember longing for a commitment to the man of my dreams, not in a wanting-to-use-men mode at all. Doog.

———

EM: I remember playing Brigadoon over and over and over again on the record player.

DA: I wonder why we were both playing it.

EM: I don’t know. I just love the album, and it was very romantic, and I…

DA: I love that album.

EM: … I was sad, and I…

DA: It was beautiful.

EM: … I wanted a boyfriend.

DA: Right, right, exactly.

EM: But I have vivid memories… That summer there was a woman I worked with at the tour company who was really nice and really attractive. She liked me. And I remember being really upset that I was never going to be able to have a relationship with a woman.

DA: Aww.

EM: And I went in to talk to you about it in your room, and I burst into tears…

DA: Aww.

EM: … and you held me while I sobbed and sobbed. Do you remember that?

DA: Well, now that you’re saying it, I feel like I do. That’s so, so sad. I think I, I think it was, like, you were kind of, like, giving it up for the last time—the hope.

EM: That was exactly it.

DA: Yeah. Oh, that’s so, so sad, though, because at that point… I know, I mean, in retrospect, I’d always admired the fact that you were so out and gay and you took a lot of crap for it. And I was kind of wavering on saying bisexual—remember all that, you know, thing—but I think that I had pretty much begun to… No, I had accepted it by then, but I… Maybe you still held on to some idea that you might somehow be able to, what, quash it or something or…?

EM: Yeah, I don’t know if I thought I could quash it, but I just was lamenting. I was sad. And I, it was just total grief. I remember just sobbing. And you were so dear—you held me…

DA: Was I? Oh, I’m so glad to hear that. ’Cause I know this is really… I remember this—now that you say it, I remember it. I just remember it was very heart-rending, and it was, it was very, very sad. It was just, like, it was, like, we, I mean, we, even though we knew lots of other gay people, there still was this feeling of loneliness in society that you just wouldn’t be—you’d always be a second-class bum.

EM: Yeah, yeah. And I never cried again about being gay after that.

DA: Is that true? I’m so glad you have that memory. That’s great.

EM: That was the last time, yeah.

DA: I’m so glad to hear of things in that summer that were positive, and it wasn’t all just that we were driving each other crazy.

———

EM Narration: Doug has no memory of reading about 41 homosexuals with the rare cancer. He doesn’t even have a clear picture in his mind of that New York Times article. But when asked about the first time I heard about AIDS, that’s always been my answer: the Hell’s Kitchen apartment, the breakfast table, the shiver up my spine. Both Doug and I were pretty naive and not connected enough to any of the city’s various gay communities to know more. That New York Times headline on page 20 came a month and a half after the city’s gay paper, the Native, had printed its first article about rumors of a new disease. People had been getting sick for at least a couple of years.

———

Shane O’Neill: It is Monday, May 3, 10:40 a.m. We’re here in Chelsea on 20th Street in the lovely home of Eric Marcus.

———

EM Narration: When I sat down to record my own oral history with Shane O’Neill, a friend who’s a video journalist at the New York Times, I started to realize that the Times article wasn’t the starting point for me. The story I’d been telling for years tethered to the public record wasn’t actually the first time I took notice—when I really heard about AIDS for the first time and it sank in bone deep.

———

EM: As I’ve come to understand, as I’ve been working on the script and the, and my own memories of this, this period, uh, I asked people—this was more than 30 years ago when I did my book—to reconstruct their memories from 30 or 40 years prior, and I didn’t realize—I knew it was challenging—I didn’t realize how challenging it was to do that.

———

EM Narration: The evidence seems to suggest that what I read in that first article had no direct impact on my life during that hot summer of independence on West 44th Street. I spent my weekdays trying in vain to get my architectural walking tour off the ground, and Sundays escorting 196 passengers on flights to and from Halifax, Nova Scotia, for a travel company called Tauck Tours. I didn’t have 10 sexual partners four nights a week that summer. When I first started thinking back, I wasn’t even sure I’d had one.

Although, it turns out, there was at least one…

———

SO: So it’s 1981. Were you dating? Were you seeing people and how were you meeting them?

EM: Summer of ’81 I don’t think I met anyone. And as Doug and I came to realize when we reminisced about this, the only person we had sex with that summer was each other. And it wasn’t even friends with benefits, I don’t, it was just, it just happened, um, ’cause we weren’t even each other’s type. Um, I met gay people in those days through—at the bars, um, occasionally.

SO: Tell me about Bob. How did you meet Bob?

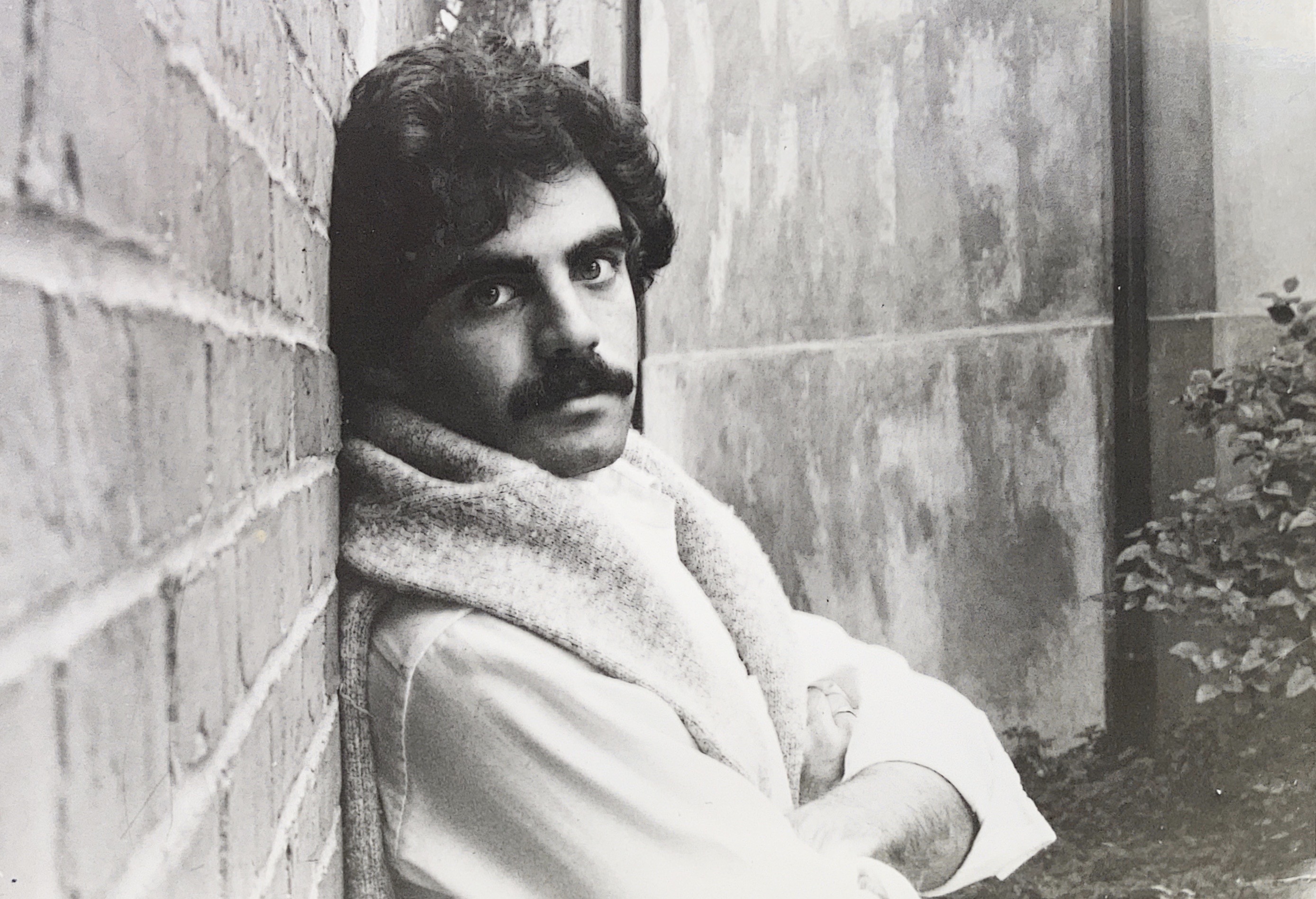

EM: I met Bob when my mother and his mother… They thought that their two Jewish sons should meet each other. And Bob’s mother told my mother that, you know, Bob was a good guy. Bob was probably 28 or 27. I was 21 or 22. Um, and… My mother had never tried to set me up with anybody. That was the first and only time she did that. And so I thought, okay. Um, and so I must have spoken with Bob by phone because there was no other way to communicate in those days. And we made a plan, and I arrived at his apartment. He lived in Chelsea, um, he lived on 15th Street and Seventh Avenue in this loft building which had been a department store. And I, I was, I’m sure I was nervous, um, because when mothers recommend a son or anyone for a date, you can never trust whether their judgment is very good. Um, so Bob opened the door. The Chelsea clone I’ll call him.

SO: What is a Chelsea clone?

EM: Back in the olden days, um, there were different kinds of gay men in New York. And the Chelsea clone was sort of the new gay guy, um, sort of hyper-masculine. He was cute. Absolutely cute. Shorter than I am, so, you know, I liked guys over six feet. Um, he was in a, in a tight white T-shirt. Um, he had this really muscly little body. Um, nice biceps—and I liked biceps. Um, and had a tattoo peeking out from under his, his T-shirt, which… Jews didn’t have tattoos in those days. Almost nobody had tattoos in those days. Chelsea clones had tattoos, and they had muscles—um, not the free-range kind, the gym kind. And he was in, uh, tight 501 jeans. I’m guessing he was in work boots because gay guys of that type wore work boots in those days and thick socks. That was the uniform.

And he lived in this studio apartment. In the front hall—it was a large studio—the front hall was a hall and a kitchen. And there was this big pasta pot on the stove boiling furiously. And I remember thinking, hm, we’re supposed to be going out to dinner, why is there pasta cooking on the stove? And he must’ve seen me look at the, the stove because—I didn’t ask him what was going on—and he said, “Oh, um, let, let me show you.” And he took a big fork, and pulled out a pair of 501 jeans that were boiling on the stove. And he explained that, that you boiled them to, so that you would break them in, and then you put them on wet so they would really fit you well. And I could see by glancing down at his jeans that his jeans really, really fit him well.

Now some of the more, um, extreme guys in those days would sand their jeans in the crotch area so that, that the jeans would be darker blue and the, the crotch area would be lighter blue so it would show off what they had in their pants. Um, Bob wasn’t quite—Bob hadn’t sanded his jeans. So I thought, oh god.

And we went out to dinner and he was really comfortable in his skin. I was not so comfortable in my skin. Um, but we had dinner and he must’ve asked me back to his place, and I must’ve said “yes” because at some point we were in his bed, um, and naked. And he was really skilled. Um, I was not his first, I was not his 10th. I might’ve been his 50th, I might’ve been his 100th. And I let him take the lead on everything and, um, we went on a second date. Um, I don’t remember—I have no idea what we talked about, but I do know we wound up in bed for a second time.

What I remember clearly is waking up in the morning, and getting dressed, and he didn’t stir. He was sleeping really, really deeply. And I don’t know if I’d ever slept that deeply in my life to not to notice when someone was getting up. And it wasn’t that he was pretending to sleep—he was out cold. And it just struck me as odd. And I got dressed. I left him a note, thanked him, um, and that was it. I didn’t write to him. He didn’t write to me. I know we weren’t each other’s type, and it just—there wasn’t magic, um…

———

EM Narration: It’s the spring of 1982. Several months have passed since I left Bob sound asleep in his bed, and my mother’s on the phone. She’s asking if I’ve heard from Bob lately. She knows we went on a couple of dates, but then I never mentioned him again, and she knows not to ask. But she’s asking. No, I hadn’t heard from Bob. “He’s in the hospital,” she says. “What happened?” I asked. “He has that new gay disease.” I almost faint.

The rare cancer in the New York Times article I’d dismissed—Kaposi’s sarcoma in those 41 homosexuals—it’s not so rare anymore. And the infections associated with this mysterious new gay disease have grown to include a terrifying list of ailments: pneumocystis pneumonia, cryptosporidium, toxoplasmosis, and various gastrointestinal miseries. My mind’s eye darts back to Bob’s apartment to the prescription bottles I’d noticed on his kitchen counter. He followed my gaze and answered a question I actually hadn’t asked. “Just some stomach trouble,” he’d said. On the phone with my mother, I’m having an out-of-body experience. All I could think about was, what was I going to tell my mother’s friends who I’d had sex with a few months after I’d slept with Bob?

Yup. My mom’s friends—a straight couple. Clearly, they had become my friends, too. They seduced me and I was willing. It was sweet. It was a little weird. They were considerably older. They were, well, they. And I was so proud of myself for having successfully had intercourse with a woman. It was my fourth try in five years. I know my persistence probably comes off a little pathetic now, but I had succeeded. Although, this was the first time with another man tagging along, which apparently made all the difference.

I felt such a sense of accomplishment for doing what comes so naturally for most men, but seemed impossible for me up until that night. And as a man, it was what I was supposed to do. Mission accomplished. I never had to do that again. Now, what to tell them? I decided to wait. If I got sick, I’d have to tell them. Anyway, it had been months since I’d had sex with Bob and I was fine. What I didn’t yet know—what none of us yet knew, what even the doctors and scientists didn’t know—was that the virus that caused AIDS, a virus that wouldn’t be identified until 1983, could hide out for years, even a decade or more, before demolishing a person’s immune system. If I had been infected, I could be a ticking time bomb—presymptomatic but in the meantime infecting others for years before I got sick and died. And before they got sick and died.

But we didn’t know any of that then. I did know I was scared. The headline had gotten much closer to home, even if it was all a big joke at the White House.

———

Reporter Lester Kinsolving: Larry, does the president have any reaction to the announcement by the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta that A.I.D.S. is now an epidemic in 600, over 600 cases?

Deputy Press Secretary Larry Speakes: What’s A.I.D.S.? I haven’t got anything on it.

LK: Over a third of them have died. It’s known as “gay plague.” [Press corps laughter.] No, it is. I mean, it’s a pretty serious thing. One in every three people that get this have died. And I wonder if the president is aware of it.

LS: I don’t have it. Are you—? [Press corps laughter.] Do you?

LK: You don’t have it? Well, I’m relieved to hear that, Larry. [Press corps laughter.]

LS: Do you?

LK: No, I don’t.

LS: You didn’t answer my question. How do you know? [Press corps laughter.]

LK: Does the president—in other words, the White House looks on this as a great joke?

LS: No, I don’t know anything about it, Lester.

LK: Does the president, does anybody in the White House know about this epidemic, Larry?

LS: I don’t think so. I don’t think there’s been any—

LK: Nobody knows?

LS: There has been no personal experience here, Lester.

LK: No, I mean, I thought you were keeping—

LS: Dr.— I checked thoroughly with Dr. Ruge this morning, and he’s had no [press corps laughter], no patients suffering from A.I.D.S. or whatever it is.

LK: The president doesn’t have gay plague, is that what you’re saying or what?

LS: No, didn’t say that.

LK: Didn’t say that.

White House Deputy Press Secretary Larry Speakes at a White House press conference, March 31, 1981.

Credit: Photo by Peneloppe Bresse/Liaison via Getty Images.

———

EM Narration: That was President Reagan’s deputy press secretary answering the first public question from the White House press corps about the AIDS epidemic on October 15, 1982.

Next time, I’ll meet you in the spring of 1983 at an unlikely night of joy and resolve—at the circus. And, you’ll meet Barry.

Postscript. I wouldn’t see Bob again for three or four years, and it was only once at a memorial service with my then partner. I can’t remember whose memorial service—there were so many by that time. Bob was in a wheelchair up toward the front of the room. I didn’t reintroduce myself and just watched him from behind. His mother had moved from California into his studio apartment to look after her only child. After he died, she stayed on for a few years more and then she died, too. I wish I could remember her name. I can’t even remember Bob’s last name. I’d ask my mother, but she’s been dead for 17 years.

It’s hard to remember. It’s even harder when everyone is gone.

———

Many thanks to our hard-working crew at Making Gay History, including story editor Sara Burningham, assistant producer and sound designer Rae Kantrowitz, deputy director Inge De Taeye, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter.

This season was recorded at CDM Sound Studios. Special thanks to interviewer-slash-oral historian Shane O’Neill and our listening circle, including Syd Baloue, Cheryl Furjanic, Dr. Jamila Humphrie, Ann Northrop, Benjamin Riskin, Jenna Weiss-Berman, and Mike Winerip. Thanks also to Doug Aucoin for sharing his memories. Thanks, Doog.

Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers, with additional scoring by Rae Kantrowitz.

This season of the podcast was made possible by the generous support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Calamus Foundation, the Kipper Family Foundation, Andra and Irwin Press, Bill Kux, Jeff Soref, Kevin Williams, Kathy Danser, Hal Brody and Don Smith, and scores of other individual supporters. Thank you so much.

“Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis” is a production of Making Gay History.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long—until next time.

###