Coming of Age During the 1970s — Chapter Six: Marching On

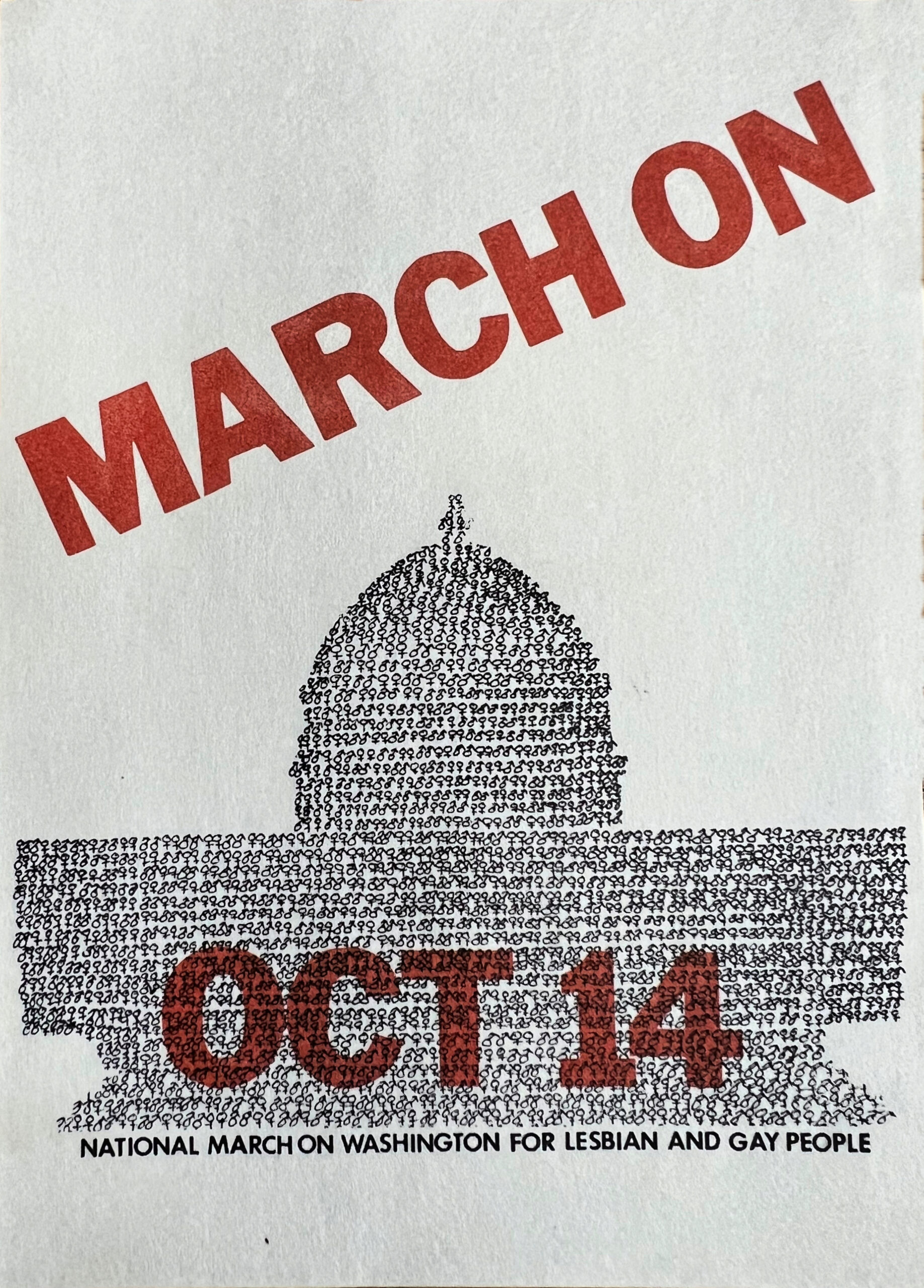

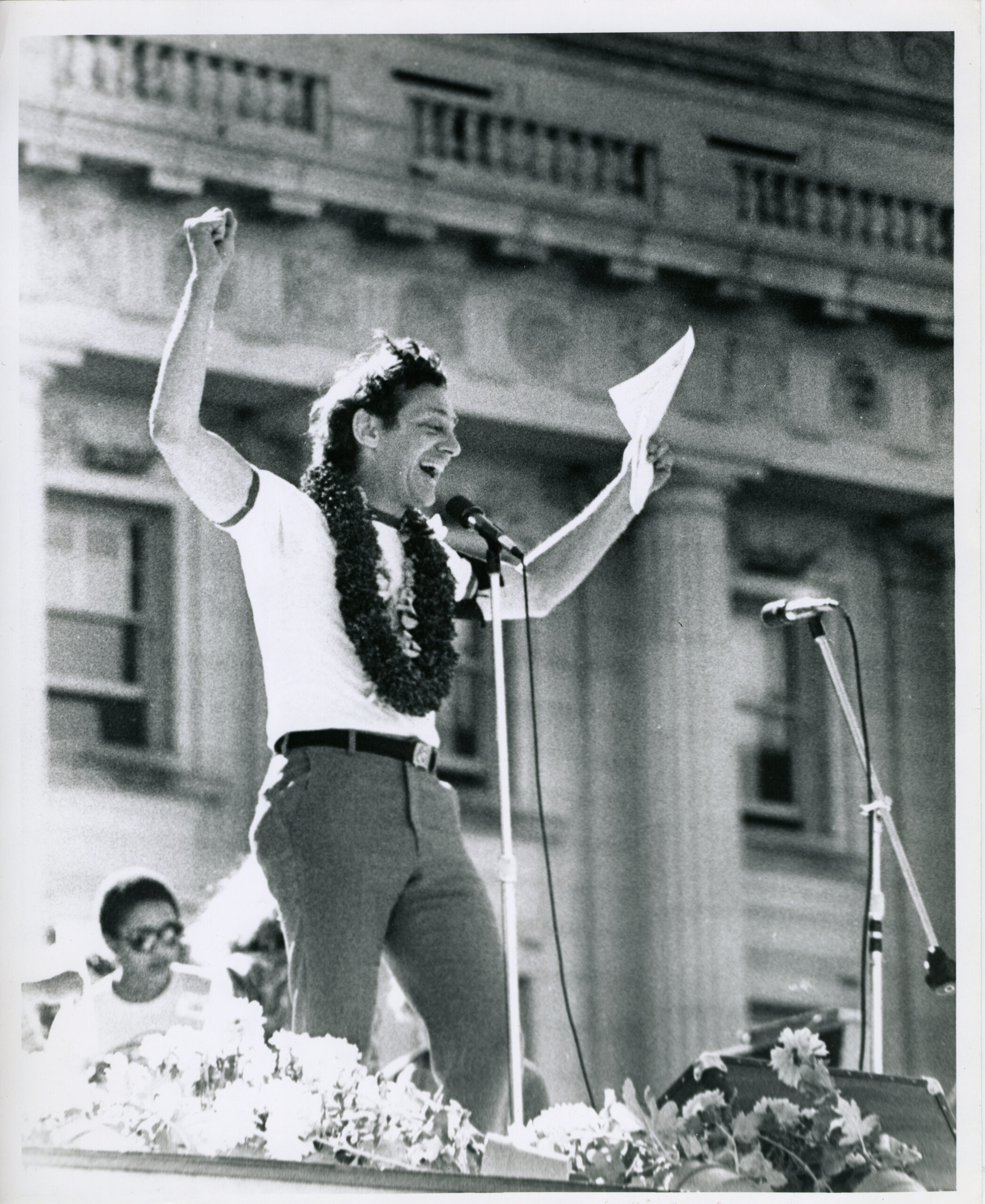

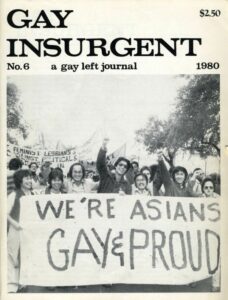

Photo taken from the cover of the album "The National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights," an LP released by Magnus Records on October 14, 1980, the first anniversary of the march. Credit: Courtesy of JD Doyle, HoustonLGBTHistory.org.

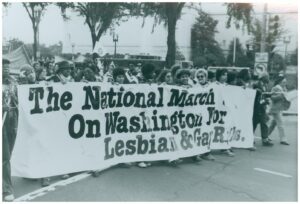

Photo taken from the cover of the album "The National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights," an LP released by Magnus Records on October 14, 1980, the first anniversary of the march. Credit: Courtesy of JD Doyle, HoustonLGBTHistory.org.

Episode Notes

In 1978 Harvey Milk calls on gay people to gather in D.C. the next year to protest the anti-gay campaigns of Anita Bryant and her ilk. Organizers are stymied by internal conflicts until Milk’s assassination galvanizes them and a date for a national march is set. But will anyone show up?

Episode first published June 29, 2023.

———

Learn more about some of the topics and people discussed in the episode by exploring the links below.

Joyce Hunter:

- MGH episode featuring Hunter with accompanying episode notes.

- Brief biographical profile of Hunter (Equality Forum).

- “Dr. Joyce Hunter: A Voice for At-Risk LGBTQ Youth” (1010WINS article and audio, May 30, 2019).

- Overview of Hunter’s papers housed at the Center Archives.

Steven Ault:

- “Marching Mad: The 1987 March on Washington,” a 2022 panel discussion moderated by Ann Northrop featuring Ault and Hunter (American LGBTQ+ Museum/YouTube; addresses the 1979 march as well).

- Overview of Ault’s papers housed at the Center Archives.

Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights (CLGR):

- A brief introduction to CLGR (and profiles of some of CLGR’s inspiring women leaders, including Hunter) by Andy Humm (Social Policy, Winter 1999).

- Overview of CLGR’s records at the Center Archives.

1977 meeting between senior White House staff and national gay rights leaders:

- Contemporary press clippings (HoustonLGBThistory.org).

- Online exhibit about the meeting (Gerber/Hart Library and Archives; click on Nationalizing Gay Rights, then Gay Rights in the White House).

- Online exhibit about President Carter aide Midge Costanza (University of Rochester).

- Article about Costanza and activist Jean O’Leary, Costanza’s partner at the time (PinkNews, December 25, 2020).

- MGH episode featuring O’Leary with accompanying episode notes.

The runup to the 1979 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights:

- Annotated text of Harvey Milk’s 1978 Gay Freedom Day speech (Liz Tracey/JSTOR).

- “‘March on Washington’ Now in Doubt” (Bay Area Reporter, November 22, 1978).

- TV news report about the assassination of San Francisco mayor George Moscone and Harvey Milk (ABC7 News Bay Area, November 27, 1978).

- Raw Super 8 footage of the 1979 march planning meetings in Philadelphia and Houston (Jim Hubbard Films).

- Article about the National Gay Task Force and other groups’ initial opposition to the march (GCN, May 5, 1979).

- White Night riots, May 21, 1979: video footage, including Randy Shilts commentary (Kinolibrary/YouTube); eyewitness account by Chris Carlsson (FoundSF; includes embedded contemporary audio courtesy of the Fruit Punch Collective).

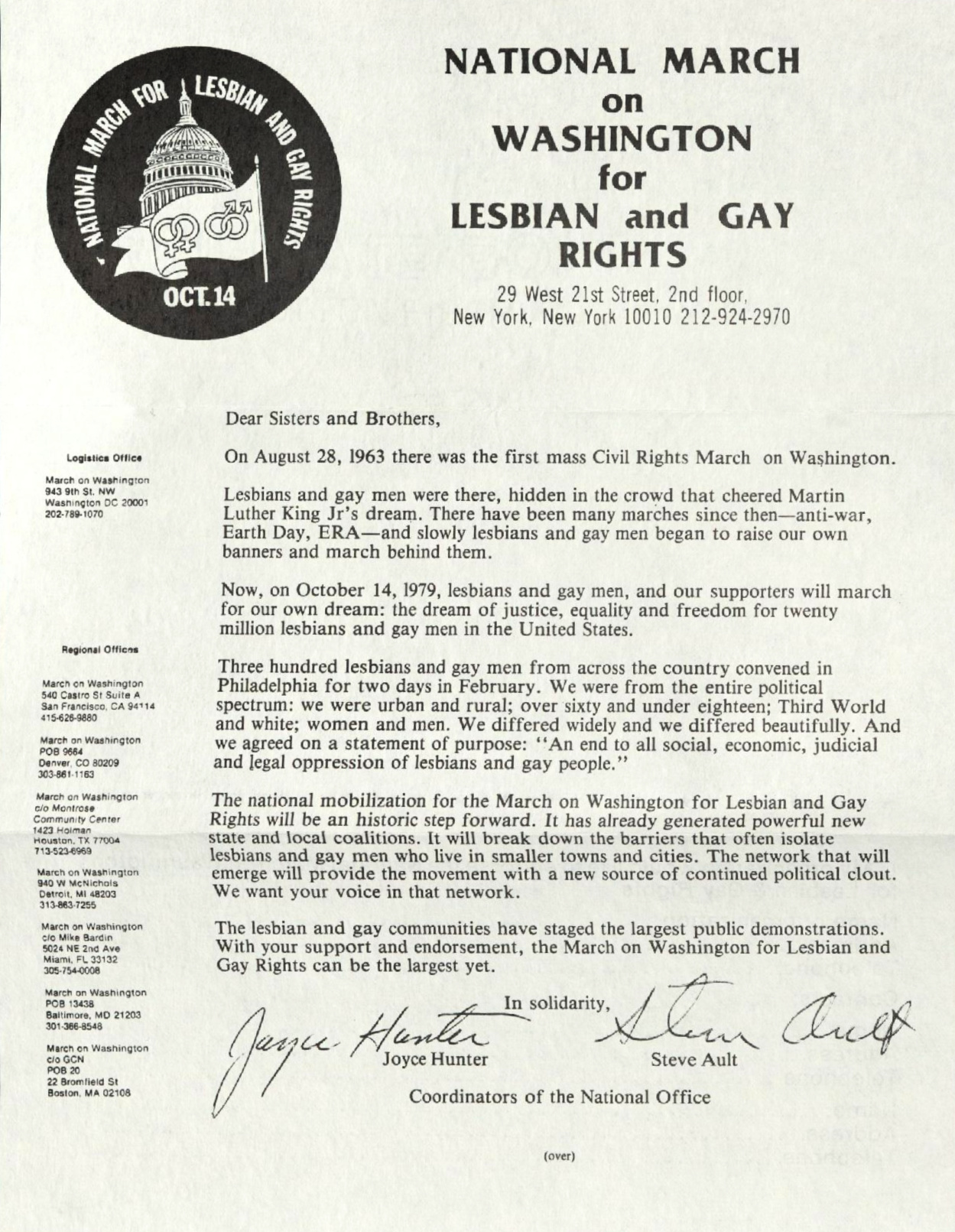

- March planning correspondence by Ault, Hunter, and Betty Santoro (W&M LGBTIQ Research Project); the final two pages speak to the galvanizing influence of Milk’s death: “This project must be carried out as a tribute to Harvey Milk.”

- Mainstream skepticism: “Gay Rights March on Mall Set Without Local Enthusiasm” (Washington Post, September 20, 1979).

First National Conference of Third World Lesbians and Gays; Asian American caucus:

- Brief conference overview (Robert Crisman/Freedom Socialist Party).

- “Slicing Silence: Asian Progressives Come Out,” an essay on queer Asian American activism before and after Stonewall by Daniel Tsang; page 20 includes a photo of Tana Loy and a transcript of her conference speech, “Who’s the Barbarian?” (UC Irvine eScholarship).

- Video interview with Tsang and additional resources related to his activism and the Gay Insurgent journal he edited (Chinese Independent Film Archive, Newcastle University).

1979 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights:

- Short video explainer (Jesse Berliner-Sachs/YouTube).

- Brief overview and reflections on the march on its 25th anniversary by Amin Ghaziani (Gay & Lesbian Review, March-April 2005).

- Webpage with links to a wealth of resources: contemporary press, photos, the march program, and an album of audio clips of several march speakers (HoustonLGBThistory.org).

Introductory resources about some of the march speakers featured in the episode:

- Paula Gunn Allen: short biography and additional resources (Legacy Project).

- Juanita Ramos: biographical essay (Our Caribbean: A Gathering of Lesbian and Gay Writing from the Antilles, 2008).

- Dr. Charles Law: obituary and additional resources (Texas Obituary Project).

- Lucia Valeska: brief profile in a 1979 issue of the NGTF newsletter It’s Time (HoustonLGBThistory.org).

- Audre Lorde: biographical profile (National Women’s History Museum).

- Blackberri: short biography and 2017 video interview (OUTWORDS).

- Howard Wallace: obituary (Against the Current, No. 165, July/August 2013).

- Kate Millett: obituary and interview (The New Yorker, September 13, 2017).

- Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: brief bio and activism overview (Columbia Law School).

———

Episode Transcript

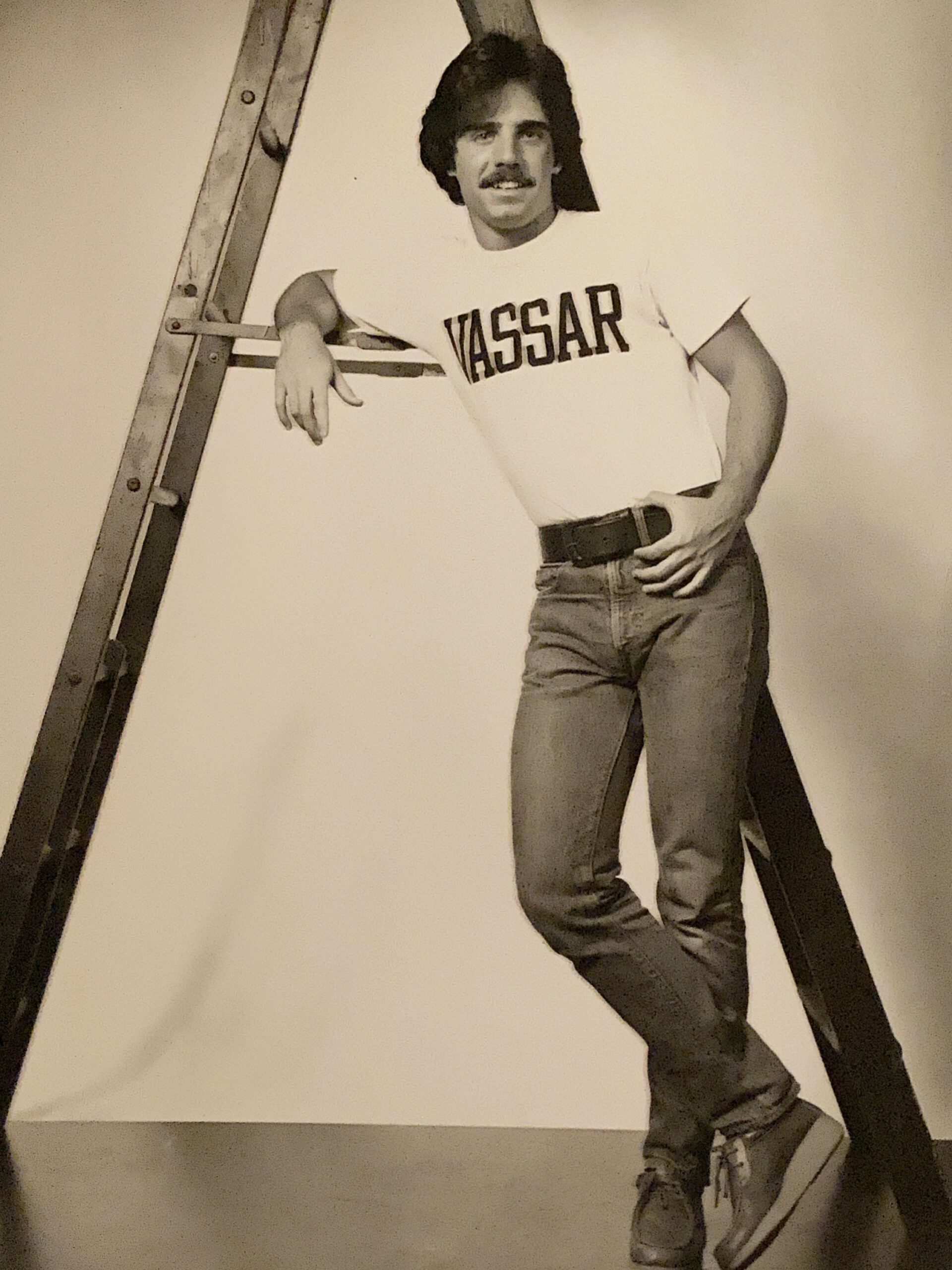

Eric Marcus Narration: As I head back to college after the summer of 1977, the summer I came out to my mother, I make a conscious decision to turn over a new leaf. I don’t want my gay identity to be the one thing people know about me on campus even before they meet me. So I get rid of my mustache, which to my mind was identifiably gay. We’d later call gay men who sported mustaches like mine, with tight jeans, Lacoste polo shirts (also tight), and work boots “clones.” I also started to make a point of avoiding the gay students I’d gotten to know through the school’s Gay Alliance organization. It wasn’t like I had any interest in being an activist. What I really wanted was to be in love, to find a boyfriend.

Around this time I decided to leave my native Queens behind, too, with a preppy all-new me. I’d already managed to ditch my Queens accent, instead of saying “shore” and “caw-fee,” like we did at Hillcrest High School, I’d been practicing for months how to say “sure” and “coffee” like my private school classmates.

If I was truly going to pass as a preppy, the clothes had to go, too. Out went the synthetic bell bottoms and floral Qiana knit shirts. They were replaced—on a shopping trip to the Roosevelt Field mall with my grandmother—by straight-leg corduroys, button-down shirts, crewneck sweaters, and penny loafers (with a penny). But still I didn’t get it quite right. Like my occasional vowel slip when I talked, my new shirts were not the requisite 100 percent cotton, and the crewneck sweaters should’ve been wool instead of polyester. My grandmother and I didn’t know any better.

A few weeks into the semester, my penny loafers and I meet Chuck (not his real name) at Deja Vu, the gay disco on the other side of the Hudson River from campus. He’s home on leave from college after struggling to sort out his identity. I show him some modeling pictures of me when I still had my mustache. He asks me to grow it back, and I do. I’m in love and if he’d asked me to shave my head, I’d have done that, too. He spends nights with me at my dorm and I introduce him to my straight friends and they embrace him, even though I have to explain to a couple of them what it means to be a homosexual.

The first weekend I stay over with Chuck in his single bed at his parents’ house a few blocks from school, his dad wakes us up for Sunday breakfast, cracking the door to Chuck’s bedroom: “Time for breakfast, boys.” A Consenting Adult fantasy that seems too good to be true. We go to the movies and hold hands. I cry as the credits roll. Chuck hands me his hanky. We head out into the night, and he tells me that men don’t cry in a tone so cold that I almost cry again. I start thinking that maybe a super-butch boyfriend in a tight Lacoste shirt and khakis whose favorite song is the Village People’s “Macho Man” isn’t the right match for me.

We were finding our way. Awkwardly. A little out of step with each other, and with the world. One step forward, two steps back.

This is “Coming of Age During the 1970s,” a production of Making Gay History. Chapter six: “Marching On.”

———

Joyce Hunter: I was hungry for learning. I was here, was, you know—just got a high school diploma. Everything was new. I was developing a vocabulary. I was becoming more articulate.

I was becoming, uh, well, angry, but the anger was very different. There was much more control, um…

———

EM Narration: That’s Joyce hunter. Some of you have met her before. Born in the Bronx to a teenage Jewish mother and an African American father, she grew up mostly in group homes, or in an abusive situation with her parents. She also survived a suicide attempt as a closeted, frightened, depressed teenage lesbian. After getting married, having two kids, getting divorced, and finally coming out, Joyce was beaten to a pulp in a homophobic attack in 1976. She was walking home from a bar with a girlfriend. The beating landed her in the hospital for a month, and when she was discharged, it became clear she could no longer work as a line cook, standing on her feet for hours and hours. So New York City’s Office of Vocational Rehabilitation sent her to get an education. She passed her GED, but that was just the beginning, as she started a new life as a gay student leader at Hunter College.

———

JH: It was a very exciting, uh, exciting time. I was in school, but let me tell you what I did. Everything was around gay issues. I was able to incorporate—and this is very important—incorporate my movement work into my schoolwork. I would write about it, I would write papers on it for sociology classes, I would go to every meeting. And while I could demonstrate, I was organizing demonstrations. And we put on a demonstration in Washington, D.C., against the Supreme Court on the sodomy issue. We made the cover of Newsweek magazine that year. We were the ones who were stamping that gay money and going out and doing demonstrations at gas stations that wouldn’t take, uh, gay money.

Eric Marcus: In New York City?

JH: In New York City, yeah.

EM: At gas stations that wouldn’t take gay money?

JH: Yeah, down in the Village. And then in ’77, when the Anita Bryant campaign, uh, happened, and, uh, we formed the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights here in New York. And I was a part of that group from the very beginning.

EM: Did you form that group in response to the Anita Bryant…?

JH: Yes. That was, that organization…

———

EM Narration: I first interviewed Joyce Hunter in 1989 for the original edition of my Making Gay History oral history book about the movement, but over the years we’ve become friends and I’ve interviewed her many more times. You’re going to hear Joyce speaking to me in interviews spanning more than three decades.

Back in 1989 Joyce didn’t go into detail about some of the ways she made her feelings known about Anita Bryant, but when we talked about it again last year, she was just a bit more forthcoming.

———

EM: Um, Anita Bryant.

JH: Oh. Her. Oh yeah, we did a big demonstration. We started, we started a whole thing—when I say “we,” it was the Coalition of Lesbian and Gay Rights. We did, uh, you know, we started to demonstrate against her, her stupid music. And, uh, so we went and boycotted orange juice. We would go into places and destroy orange juice. We felt bad, but we did, we did it anyways.

EM: You’d go into grocery stores?

JH: Yeah. And put holes in anything that had her name associated with.

EM: So, um, in, in orange juice containers, you would puncture them.

JH: Yeah.

EM: Yeah.

———

EM Narration: Beyond direct action against juice cartons in grocery stores, like Joyce said, she put her anger into action in more controlled ways, too, joining the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights in New York in the summer of 1977. The CLGR brought together about 50 gay organizations in New York, including GAA and Lesbian Feminist Liberation. That same summer, there was a National Gay Leadership Conference in Denver. Joyce didn’t go, but she was paying attention to what they talked about.

———

JH: They felt that, uh, because of the Anita Bryant, the backlash and all of this, that this was a time to march on Washington, and they wrote a position paper and they sent it out to all the universities and stuff like that, and I got one. And I filled it out saying I was interested in working on this march. You know, a student leader. Sent it off.

———

EM Narration: Joyce heard nothing back, and she just kept on with all the other organizing, studying, and demonstrating she was already doing.

In the summer of 1978, I turned my attention to Washington, D.C. I was not going back to Queens. My preppy persona was paying off, and I’d secured an internship in the nation’s capital at a real estate development company. I also snagged a house-sitting job for a Seven Sisters alum and her Ivy League husband, both graduates from the 1940s. They owned a handsome brick house in the northwest of the city. In the old days, we might have said there was a whiff of lavender about that marriage. She was butch and he very much enjoyed taking photos of me in my Speedos. I can’t tell you how it happened. I can tell you we were all pretty sure each other was gay, and none of us ever said anything.

When they left the city for the summer, their house became the perfect place to host my new boyfriend, a 29-year-old assistant to President Jimmy Carter. We met at a disco soon after I started work as a lifeguard at the Quality Inn on Capitol Hill. I’d scrambled to find a job after the real estate internship evaporated days after I’d arrived in D.C.

Jim, my boyfriend, invited me on a tour of the White House. We were walking down the colonnade—you know, the one you always see in pictures of the president walking with someone famous, or in that video of President Obama and then-Vice President Biden running along? That’s where we were when my heart stopped.

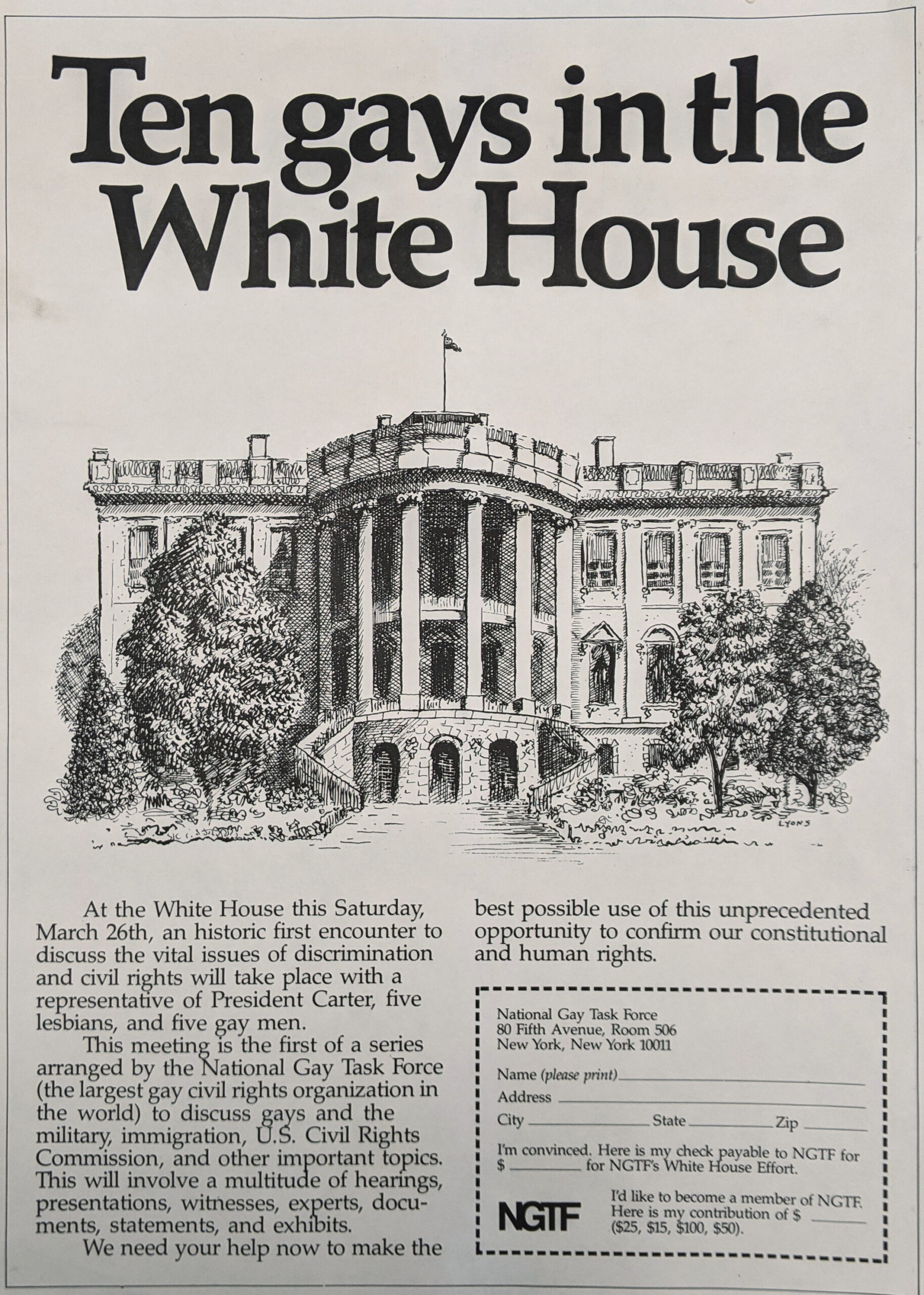

On this typically hot and humid afternoon in July 1978, Midge Costanza was walking toward us. The first woman to serve on the senior White House staff, she was an assistant to President Jimmy Carter, advising him on social issues. But I knew Midge’s face from the news reports about a March 1977 meeting she’d held with national gay rights leaders at the White House. Actually, it was the meeting with gay rights leaders at the White House; there’d never been one before. Midge was my hero.

It’s hard to imagine now what a big deal that meeting was, but seeing openly gay people inside the White House, meeting with the administration, at the height of Anita Bryant’s Save Our Children campaign? When a ban on employing gay people in the federal government had been lifted just two years prior? The symbolism and the achievement were striking.

So I just about threw myself at Midge’s feet. I somehow knew that she was gay like me. Hard to say what tipped me off—maybe her close-cropped hair, her manner. And the fact she risked her career to arrange the first such White House meeting. And of course Jim was gay and I was gay. But we were at the White House, in our suits. And Midge was in the closet. So when I gushed about my gratitude for what she’d done, what that historic meeting had meant to me, it was super awkward. Midge was clearly so uncomfortable. She kind of nodded, said thanks, and was gone.

Years later I’d hear the story that while Midge was in the closet, her lover at the time was not. Jean O’Leary was the co-executive director of the National Gay Task Force. One of the people who was at that first White House meeting in 1977. Jean had put the White House meeting on Midge’s agenda, saying, “It’s time, Midge,” when she rolled over in bed one night. But I digress.

Most of the organizations involved in the July 1977 leadership conference in Denver that Joyce Hunter told us about—organizations including the National Gay Task Force, the Metropolitan Community Church, and the Gay Rights National Lobby—had decided against having a march on Washington. Here’s Joyce Hunter again.

———

JH: What happened was, there was real misogyny and racism was part of the issue for them, and they could not get it together and decided if they couldn’t do it, then nobody could do it.

———

EM Narration: At the time, the national groups said they worried there wasn’t enough infrastructure to support a big march. They wanted more time to fundraise and organize and build a national mass movement that could make it a success. They were worried about a march blowing up the hard work they’d put into lobbying Congress for a gay rights bill and getting that meeting at the White House. Whichever version is true—and experience suggests it was probably all of the above—not everyone was on board with the national leadership’s hurry-up-and-wait attitude. Especially not the de facto gay rights leader of the West Coast, San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk. Harvey had always maintained that visibility was the key.

———

Harvey Milk: We must continue to speak out, and most importantly—most importantly—every gay person must come out.

———

EM Narration: Around the same time as I was falling at the feet of a closeted Midge Costanza at the White House, Harvey Milk spelled out his vision for a national march in a speech in San Francisco on Gay Freedom Day—June 29, 1978, the ninth anniversary of the Stonewall uprising. Harvey was railing against the Briggs Initiative, Anita Bryant’s campaign of hate, and homophobic bigotry in the press. And he argued passionately for coalitions, for gay people to fight for the rights of all oppressed people.

We have searched high and low for audio of this speech, and have turned up this one short clip…

———

HM: … for that march on the Day of Freedom in Washington, D.C., on the same spot where over a decade ago Dr. Martin Luther King said, “I have a dream.” A dream, a dream that is fading, a dream that has become a nightmare…

———

EM Narration: Let me read you some more from that speech. “I call upon all minorities, and especially the millions of lesbians and gay men, to wake up from their dreams, to gather in Washington and tell Jimmy Carter and their nation, ‘Wake up. Wake up, America. No more racism, no more sexism, no more ageism, no more hatred. No more!’ It’s up to you, Jimmy Carter. Do you want to go down in history as a person who would not listen, or do you want to go down in history as a leader, as a president? Jimmy Carter, listen to us today, or you will have to listen to all of us from all over the nation as we gather in Washington next year.”

And just in case President Carter didn’t catch his speech, Harvey mailed him a typed copy, with a note urging the president to take on a leadership role in defending the rights of gay people. It just occurred to me: I wonder if my boyfriend Jim opened that letter.

When Harvey Milk made his Gay Freedom Day speech in June 1978, he was pretty much a lone voice on the national stage still backing a march. That’s how Joyce Hunter remembered it, too. She said Harvey didn’t care about the disagreements; he was full steam ahead.

———

JH: They couldn’t get it together and they decided to drop it. Harvey Milk, however, was still interested. Went back to San Francisco, and he, um, he wants to start a march committee in San Francisco and is gonna try and get people around the country interested…

EM: So you knew Harvey Milk.

JH: Not really. I didn’t know—I, I don’t want to say that I knew him. We really been—I really didn’t know him. Um, however, our organizations were in contact with each other. I’m talking about the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights now.

———

EM Narration: But even Harvey Milk couldn’t get plans for a national march going just by starting a committee in San Francisco, and it really looked like his vision was out of time. Some of the momentum for the march was lost when the anti-gay Briggs Initiative was defeated on November 7, 1978. Sometimes, wins can take the wind out of our sails, and our eyes off the ball.

On the night of November 27, 1978, Joyce Hunter was at a meeting of the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

———

JH: And uh, then, uh, we got a call from San Francisco. And we were here in New York and it was late at night.

———

Dianne Feinstein: Both Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk have been shot and killed.

[Crowd gasps, exclaims.]

Unidentified Voice 1: Jesus Christ!

DF: The…

Unidentified Voice 2: Hold it, hold…

[Shushing.]

Unidentified Voice 3: Quiet, quiet, quiet.

DF: The suspect is Supervisor Dan White.

———

JH: … which was awful, because the call told us that Harvey was dead, that somebody had assassinated him that evening. And the coalition, we said, well, I said, “We have to do this. We have to do this for Harvey, if nobody else, and the mayor.” I mean, they killed him and the mayor—they were assassinated in San Francisco. So we said, we’ll do this march.

And we really want this to happen, so we decided to have a national conference on whether or not to march. And we decided to have it in Philadelphia in early ’79.

———

Unidentified Conference Voice 1: Excuse me, Johnny. Will everybody who wants to speak keep their name up until your name has been taken down?

Unidentified Conference Voice 2: Let’s get in line.

[Crosstalk.]

Unidentified Conference Voice 1: Everybody wanna get in line?

[Crosstalk.]

———

EM Narration: The issues of racism and sexism, respectability politics, and logistics that had been too much to overcome the last time a national march had been mooted hadn’t gone away of course. But in their shock and grief, a surge of energy brought people together from organizations around the country, to Philadelphia.

———

Unidentified Conference Voice 3: Covering the National March Conference, Saturday, February 24, 1979.

Unidentified Conference Voice 4: As you’re all aware, Harvey was murdered—30,000 people in San Francisco held a spontaneous memorial service. There was a great deal of concern in the San Francisco community as to what we could do there to continue on the work that Harvey had started in terms of gay liberation and equal rights for gay people.

———

EM Narration: Three months after Harvey Milk’s assassination, the first item on the agenda at the Friends Meeting House asked delegates to decide whether to hold a march. There was still far from unanimous support.

———

Unidentified Conference Voice 4: One of our main concerns was that this would be an inclusive effort, whereas many other efforts which were rumored to be occurring were not inclusive.

Ed Cruickshank: Eddie Cruickshank from New York City, the National Rainbow Alliance of the Deaf. Gay deaf citizens, who are our brothers and sisters, fully support a march on Washington this year.

[Cheering.]

Steve from Delaware: Steve [indistinct], I’m chairman of the gay community of Delaware. I admit, as everyone here must know, that we are oppressed by laws and by attitudes. A good friend of mine is now in prison in North Carolina for a consensual homosexual act. A march would demonstrate our concern, our fervent hope, that this oppression be destroyed, but it would only demonstrate that concern. Marching would not change laws, demonstrating would not change attitudes. A march by itself will not achieve our goals. It will push them further away. Consider the damage you will do to those of us who have worked hard to secure laws and are still pushing for them, rather than getting together to have a party in the streets.

Kathy Dennis: My name is Kathy Dennis. I’m a member of the gay caucus of Youth against War and Fascism. For seven years, many of us have watched and listened as, time after time after time after time, gay rights legislation was defeated in New York. We have watched nationwide as referendums have defeated us in city after city after city, but it was only after our defeats that we started to realize our strengths. That we took to the streets by the thousands, by the hundreds of thousands, and made possible the victories that we’ve been able to celebrate this year.

Unidentified Conference Voice 5: Now, I think it’s very unfortunate if we here today speak about this march only in terms of lesbians and gay men. I’m sick and tired of having our movement limit itself to men and women. We have youth in our movement and I think that they need our voices heard.

KD: We are not asking for rights. We are saying we will have our rights at all costs.

[Cheering.]

Luvenia Pinson: My name is Luvenia Pinson and I’m a member of Salsa Soul from New York and the Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee. At some point, we have got to come out of our communities. We have got to escalate the struggle. I’d like to remind the men in this group that the women have already voted and endorsed a march for 1979.

[Cheering.]

Unidentified Conference Voice 6: I don’t really give a damn about the legislation. They’re not gonna give us our bill. What we can do is we can get our sisters and brothers on the streets of Washington saying that we are everywhere. We’re gay, we’re proud, we’re strong. And this year is the year.

Unidentified Conference Voice 7: I give a great deal of a damn about the legislation. I give a damn about legislation that is not enacted so that people are afraid to come out of the closet lest they lose their jobs, or who have lost their jobs because they’ve come out of the closet. I give a damn about courts who would deny custody to lesbian mothers and gay fathers and even deny visitation rights to them. I think that we must concentrate on those issues and not on the great big coming-out party that you’re talking about, with all the shouting and stamping and clapping, as if that were the only issue we had to say is, “Gay rights now.”

Steve Wilkins: My name is Steve Wilkins. I represent the Texas Gay Task Force in the Dallas gay political caucus, and I wanna say howdy from Texas. Let’s relax and be friendly. The enemies out there are not in here. [Applause.] I wanna tell you how hard it is to come out in Texas. It’s easy to talk about gay pride in San Francisco. Let me tell you about Texas. I can’t say, “Go to Washington and everything’s gonna be okay.” I can’t say, “Come out of the closet. In six months, go to Washington.” It’s harder to get there from Texas, psychologically and physically. We want time. Gay people are everywhere; let’s make this a national march and let’s give us the time to make it significant. And I’m talking about New Mexico and Oklahoma and Louisiana, too—not the three major cities that are well-represented here. We haven’t had all the years you have. We need the time. Thank you.

[Applause.]

Zhane Gray: My name is Zhane Gray, a member of Salsa Soul Sisters. First of all, I’m Black, I’m lesbian, I’m a lesbian mother, and I think I have taken part in just about more marches than anybody, starting for Black bus drivers and policemen and post office workers with Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., in New York. So I don’t want anybody to tell me about oppression. Politicians, all who are liars and speak with forked tongue and outta both sides of their mouths, only understand one thing and that is numbers. For years, they have been saying that we do not exist. We must show them that we do exist. We must show them that we have gay youth that do not need a psychiatrist’s couch. [Applause.] We must show them, we must show them that we have had people that live long enough to get gray hairs without becoming junkies and alcoholics and adverse people. We must show them that first, foremost, and always, we are human beings and we are their constituents. They must deal with us. And when we go to Washington, we are here to say, “Here I am, and I want what’s mine.”

[Cheering.]

———

EM Narration: The conference endorsed a march, to be organized on a grassroots level and led by a steering committee made up of 50 percent women and 25 percent people of color.

———

JH: You know, we worked our butts off, and we didn’t have any of the communications networks that you have today, but we made one. I was still at Hunter College. I was a student there and, you know, being a person of color, I went to the people of color community and I said, “We all gotta be involved.” I said, “It isn’t a white man’s march. It’s gotta, it’s gotta be all of us.”

———

EM Narration: The handful of national organizations that existed at the time were still reluctant to join in. These organizations were new, they were small and underfunded, and they couldn’t foot the bill for all the organizing involved in holding a huge march. Without that funding, their leaders feared few would attend.

———

EM: They were opposed to the march.

JH: Opposed. Also felt that we couldn’t do it—you know, a bunch of lefties in student groups and, you know, couldn’t do this kind of thing. And, uh, …

EM: Did they feel it would be an embarrassment if it flopped?

JH: Yeah. They were concerned about it flopping and that these people don’t know what they’re doing, you know. And, and the funny thing was, we were all known for doing major demonstrations and organizing them.

———

EM Narration: Joyce had met Steve Ault—a gay rights activist with deep experience in the anti-war movement—in 1977. Steve was part of the group protesting with Joyce against the Save Our Children campaign and an anti-sodomy case before the Supreme Court. Steve was also one of the founding members of the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights. He and Joyce became close friends. Well, they needed to be. They would be working very closely together in the coming months. Steve started working as a coordinator of the march on Washington after the Philadelphia meeting, and he called Joyce in July of 1979 to ask her to become a co-coordinator of the national march—a march that no one was sure they could pull off.

———

JH: He came to me and said to me, “We’re going to meet in Houston.” And he says, “I would like you to be the co-coordinator.” And I kind of looked at him and I said, “Oh my god.” I said, “We’re”—and this is supposed to happen on October 11. October. This is July, and we really haven’t, we have no support, none of the major organizations that can do this. He says, “I’m sure that we can pull it together in Houston.” And we did, we pulled it together. We did the outreach that was needed to be done…

EM: So it was you who were the co-coordinators of this then.

JH: Steve Ault and myself.

EM: You and Steve Ault. This was your baby.

JH: I don’t consider that march my baby. I made it move.

EM: They called you in to get it mo—to get it going. To get it done.

JH: To get it moving, yes. They called me in to get it moving.

———

EM Narration: When I listen to that interview with Joyce, I am again reminded of how incredible her drive has always been. She was still a student at Hunter College, a mom, recently recovered from a very bad beating, and she was just doing it.

Now, Joyce would be the first to say that no single person could pull together a national march in fewer than six months. The germ of the idea had started as a response to Anita Bryant’s Save Our Children campaign, but there just wasn’t the money or the truly national outreach to make it happen in 1977. In reality, it wasn’t there in early 1979 either. But then in May of 1979, the grief and rage in the immediate aftermath of Harvey Milk’s assassination was reignited.

On May 21, 1979, Dan White received the lightest possible conviction for the killing of Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone: voluntary manslaughter. That night, the streets of San Francisco erupted.

———

Unidentified Reporter: The breaking glass, the angry crowd, and the screaming sirens that you just heard were recorded Monday night at San Francisco’s Civic Center. On Monday night, it was gay people, openly gay people, lashing out their frustrations at a society who, by its very structure, stands as an oppressor to gay people. Rocks; bottles; fire; strong, angry words were thrown at the symbol of that society—City Hall—and its protectors, the San Francisco Police Department.

———

EM Narration: The evening started with a peaceful march from the heart of the city’s gay community, the Castro, …

———

Chanting Crowd: Out of the bars, into the streets!

———

EM Narration: … protesting in part the San Francisco police—Dan White was a former cop.

———

Chanting Crowd: Dan White, Dan White, hit man for the New Right! Dan White, Dan White, hit man for the New Right!

———

EM Narration: But violence broke out near City Hall and then it was a riot. Squad cars were set on fire, billy clubs flew, arrests were made. When that was quelled, the police weren’t done.

———

Unidentified Reporter: Later that evening, the police entered the Castro in large numbers, causing the people to come out of the bars screaming, “Get out of our neighborhood.”

———

Chanting Crowd: Go home! Go home! Go home!

———

Unidentified Riot Witness 1: All of a sudden there are, you know, more cops everywhere and they start lining the streets. Uh, and a few people started throwing bottles at them. Uh, and then they’d just go crazy. Uh, they chased people back into the bar, where we thought we were safe.

Unidentified Reporter: Sticking my microphone through the broken window, the front door.

Unidentified Reporter: Were you in the, were you in the bar when…

Unidentified Riot Witness 2: Yes, I was. We were sitting at the same table. Honey, come over here. We were all sitting at the same table, relaxed, having a cocktail. I’d just ordered a round. The police bashed through every one of these windows, billy-clubbing everybody through that small little back door in rear…

Unidentified Riot Witness 3: I followed [indistinct] to protect myself.

Unidentified Riot Witness 2: … saying, “Get out. Go home, queers. Get off the streets.”

Unidentified Riot Witness 3: This woman cop comes up to me and kicks me in the ribs, telling me to “Get your fucking ass out.” That’s what she said.

Unidentified Riot Witness 2: A big woman police.

Unidentified Riot Witness 4: They finally got us out [crosstalk] the back door. They got into formation and marched, saying, “Go home, faggots. Go home, faggots.”

———

EM Narration: People were angry, grief-stricken, and they’d had enough. The White Night riots, and the police brutality that followed, were some of the most striking manifestations of gay anger—and state violence toward that anger—since the Stonewall uprising.

The momentum for the march on Washington seemed to kick up a notch in the wake of the riots. The National Gay Task Force had been one of the last national organizations to come on board. By September of 1979, a month before the march was set to step off, it was becoming clear that people from around the country were going to stream into Washington in large numbers, so the Task Force at last signed on.

The march had five main demands:

- Pass a comprehensive lesbian/gay rights bill in Congress.

- Issue a presidential executive order banning discrimination based on sexual orientation in the federal government, the military, and federally contracted private employment.

- Repeal all anti-lesbian/gay laws.

- End discrimination in lesbian-mother and gay-father custody cases.

- Protect lesbian and gay youth from any laws which are used to discriminate, oppress, and/or harass them in their homes, schools, jobs, and social environments.

We’re still waiting…

———

Unidentified Conductors: … Amtrak 6 … Get ’em moving, Tony … All aboard!

Chanting Marchers: Freedom train, freedom train, freedom train, …

———

EM Narration: The Gay Freedom Train was an Amtrak train that traveled from San Francisco to Washington, D.C., picking up marchers along the way. It provided visibility for the march and for gay people wherever it stopped. Robin Tyler helped organize it.

———

Robin Tyler: I thought that while a train was going across mid-America, it would be a good chance to reach out to the grassroots people that could not participate in Washington…

———

EM Narration: By the way, Robin was the first lesbian to come out on national TV, a year before, in 1978.

———

RT: … and stop and speak to people across the country who could not participate, and that way do outreach, and to, uh, all kinds of cities. And so I think that’s what the train is about. It’s definitely a freedom train where, if gay people and lesbians can’t get to us, we are getting to them.

———

Chanting Marchers: Freedom train, freedom train, freedom train, …

———

EM Narration: As tens of thousands were on their way to Washington, D.C., and beginning to gather for the first national gay rights march, another groundbreaking “first” was getting underway in the nation’s capital: the first National Conference of Third World Lesbians and Gays. It was a three-day conference of workshops and speeches organized by the National Coalition of Black Gays. The conference was held at Harambee House, a then-new, Black-owned hotel next to Howard University. Around 500 people attended. They workshopped and heard speeches that fought back against the dominant voices of the movement. It was a place to speak and be heard, and it created a vital space for people to see each other and be seen like never before.

———

Tana Loy: My name is Tana, my Chinese name is Leung Lai Jin, and I feel especially fortunate to share with you what happened to us as the Asian American caucus, what happened to us personally and politically, within the context of this history-making conference. We, Asians, gay Asians—and that means Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Indonesian, Vietnamese, whether we’re from Guam, Korea, Malaysia, whether we’re Indian, whether we’re Pakistani. We have for the first time for many of us with open hearts and minds run towards each other. [Applause.] And we have great—we have embraced each other. And we all know that for a Third World lesbian or gay man to do something that personal is highly political.

We’re silenced even from each other by the racism and the sexism that exists in this country. That manifests itself in the fears and frustrations that keep our people in the closet as Asians and as lesbian and gay men. Many of us cannot even come out for fear of deportation, and yet I know that there are many Asians who are gonna be out on that street tomorrow, knowing that that’s a reality in their lives.

———

EM Narration: Deportation was a reality for many marchers. A 1952 statute barred gay people from abroad from entering the country, and was confirmed in a 1967 Supreme Court ruling that a homosexual individual could be deported from the U.S. on the grounds of “psychopathic personality.” By the way, that law stayed on the books until 1990.

On the eve of the march, the Washington Post reported that while organizers were expecting up to one hundred thousand people, “bickering among march leaders and indifference by some national and local groups are expected to reduce that number.” When I talked to Joyce Hunter in 1989, she remembered the battle over expectations very clearly.

———

JH: We were trying very hard not to play a numbers game, uh, you know, with the press. And of course the Washington Post said that we were young and enthusiastic, after interviewing me and Steve, uh, but they didn’t think that we were gonna pull this one off. It was terrifying and exciting at the same time. And I was so afraid. I, I didn’t want it to fail. There was no way that—I said, “We’re not gonna let this thing fail.” It was very scary. I, I just got that feeling back. Uh, it was very scary. I was afraid of failing.

———

Chanting Marchers: We are everywhere, we will be free…

———

EM Narration: The march stepped off Sunday morning, October 14, 1979. It was a whole new kind of visibility. Just over 10 years before, gay rights marches were virtually silent. Homophile organization members would dress in shirts and ties, skirts and pumps, and respectfully parade in circles carrying signs asking for the right to work for the government or to not be evicted for being gay or thrown out of the military. Now thousands upon thousands of gay people were in the nation’s capital. It was the largest gathering of gay people anywhere, ever.

I’m going to read Dan Tsang’s account of what he saw, reprinted in the Gay Insurgent, a Philadelphia gay paper. Dan is a renowned Asian American queer activist.

“The early morning march through the Black neighborhood and through Chinatown was the first time Black and Asian lesbians and gay men had paraded through our own neighborhoods. The mood of the marchers was jubilant, and the reaction from onlookers more surprise than hostility. The dozen or so Asian lesbians and gay men chanted, ‘We’re Asian, gay, and proud!’ as the street signs turned Chinese at the edge of Chinatown.” Tsang continues: “Heading the Third World contingent was a small group of Native Americans, holding a sign proclaiming ‘The First Gay Americans.’”

———

Ray Hill: My name’s Ray Hill and I’m from Houston, Texas. They tell me that Anita Bryant wants to outlaw homosexuality in this land, and I’m not gonna tolerate that because there were homosexuals on this land before the white folk came that she is a member of. And one of them is going to speak now—from the American Indian Gay Movement, it is my pleasure to introduce Paula Gunn Allen.

Paula Gunn Allen: I’m here as a gay American Indian, and I’m very proud to represent the people who have the longest gay history in this hemisphere. Long before the patriarchy brought its separation and its hate and its walls to this land, homosexuality and lesbianism were revered and honored among their people.

———

JH: The day of the march, that was exciting, watching them come in. We were on the stage in the back.

EM: So you were on a stage at the end of the Mall, close to the Capitol.

JH: Right.

EM: And so you watched as people came in.

JH: Yeah. It was exciting. You wanted to cry and yell and be happy. And so proud. Very proud.

EM: Why?

JH: Well, because we all got there.

———

Ray Hill: And it is my pleasure to introduce Juanita Ramos and Armando Gaetan.

Armando Gaetan: Greetings, you beautiful, multicolored people. How you doing out there? Greetings from this Chicano from Massachusetts. Greeting from El Comité Latino de Lesbianas y Homosexuales de Boston. Greeting from COHLA from New York. Greeting from the national organizations of Latino lesbians and Latino gays. We love you.

Juanita Ramos: Don’t allow other oppressed lesbians or gay men oppress you because you happen to be from a different ethnic group. Take the anger that you feel and tell the white lesbian and gay movement that we’re here to stay, that all of us as oppressed persons have to unite together instead of attacking one another. That racism and sexism in the lesbian and gay community only serves the interests of our enemies who wish to keep us divided.

———

JH: Well, we had people come and speak.

———

Ray Hill: The Reverend Dr. Charles Law.

Charles Law: And I’m afraid that we will find that those gay people who do not come across as being offensively gay, militantly gay, obviously gay, adamantly gay, or admittedly gay will be the ones to reap the benefit of the open, heartfelt expression of this hypocritical society. And it will be those individuals who will reap the benefits of this struggle and the sacrifice of all of you and of Harvey Milk. And the real sissies and the butch women in this country will still have to live in gay ghettos and not have achieved the true import of this movement.

———

JH: Y’know, politicians…

———

Ray Hill: Member of Congress, Representative Phil Burton from San Francisco.

Phil Burton: This is a watershed event in terms of bringing to the gays and lesbian women freedom, and the elimination of oppression as a matter of instrument of governmental policy. I predict today that we are going to win this battle to bring long overdue justice to the oppressed and the gay and lesbian communities. Thank you very much.

Unidentified Emcee: And now it gives me great privilege to present, from one of the most important organizations and the largest in the country, from the National Gay Task Force, Lucia Valeska!

Lucia Valeska: I love you for marching for me. But it’s harder for some than for others. On this day, we march for our right to work gay, to have our children gay, to love gay. We’re here in Washington to show the world that we’re here, we’re everywhere. Ten years ago we shouted “Gay Is Good.” Now we’re here to prove it!

Unidentified Emcee: The fantastic Audre Lorde!

Audre Lorde: I am proud to raise my voice here this day as a Black lesbian feminist committed to struggle for a world where all our children can grow free from the diseases of racism, of sexism, of classism, and of homophobia—for those oppressions are inseparable. With this march on Washington, each of us has a responsibility to take this struggle back to her and his community, translate it into daily action. For not one of us will ever be free until we are all free.

Unidentified Emcee: Please, how about a great gay/lesbian welcome for the great gay Blackberri!

Blackberri: I would like for the media not to do a white-out on all the Black people that were here today because that—or any of the Third World people, as far as that goes—because that happens to us a lot. I mean, we put our energy into the, the gay community and a lot of the white people get the focus, but we don’t get nothing. So, this is for you.

[Singing:] When your icebox is bare, eat the rich…

Ray Hill: It is my pleasure to introduce, from San Francisco, Howard Wallace.

Howard Wallace: We are sliding into a deepening recession that some leading economists predict will become a major depression. In such times, every kind of social inequality always becomes magnified. Crude and primitive scapegoating of minorities who are weak, isolated, vulnerable, or simply different is becoming commonplace. We are presently sitting ducks for these misdirected, pent-up hatreds. Powerful people are setting us up, portraying us as alien to other progressive movements. In spite of these ominous times, we have reason for optimism.

Blackberri: [Singing:] Eat the rich, yum, yum, yum, yum, yeah, eat the rich, yum, yum…

Unidentified Emcee: Kate Millett, brilliant, genius, dedicated, loving, radical feminist!

Kate Millett: In 10 years we have gone from not even being a word you said in public to a great national force. We have come through the persecution of love to its restoration, but don’t forget: we’re outlaws. It’s our great advantage. That’s why I recommend it to you.

Unidentified Emcee: Florynce Kennedy!

Florynce Kennedy: Remember tomorrow, you are not just gay. You are not just oppressed. You are taxpayers. You are voters. And you are consumers. And you’ve got power! You’ve got consumer power! You’ve got woman power! You’ve got lesbian power! You’ve got parent power! And you’ve got gay power!

This song is dedicated to Anita Bryant.

Nothing could be sweeter than to find out that Anita is a lesbian

Nothing could be finer than her sharing her vagina with a woman

Even if she tried it out for only one day

She’d find out what fun it is to be gay

But instead she sours civil rights in Dade and Broward

She’s a lemon.

Give ’em the fist, yeah! Thank you!

———

EM Narration: Anita Bryant might even have been close enough to hear it all. The Washington Post reported a press conference and prayer service was to be held on Capitol Hill the same time as the march, organized by a Christian religious coalition including the Rev. Jerry Falwell and Ms. Bryant.

———

Unidentified Emcee: Goodnight! Thank you! Thanks to the organizers, thanks to the public, thanks to anyone, thanks to the press, thanks to the millions upon millions of gays that [indistinct] this national march on Washington! Thank you! Thank you so much.

———

EM Narration: It’s so vivid. Almost feels like being there. Almost. But I wasn’t there. Vassar’s Gay Alliance arranged for a bus to make the five-hour trip to D.C. for the march. I didn’t sign up. I was still staying on the margins of anything that smacked of activism or protests because it made me uncomfortable—a little afraid to be honest. What I told my gay classmates who were going was that I had too much work to take the time away. There was another reason. One that I’m not very proud of and have never confessed before. Do you remember the kid at the back of the school bus or the bus to summer camp who threw up on cue? That was me. I’m desperately sensitive to motion and even if I took Dramamine, I knew I’d throw up on the way to D.C. And more than likely on the way back to Vassar, too. So there was no way I was getting on that bus.

But that didn’t keep me from joining my gay classmates at the student pub, which was called Matthew’s Mug, the evening before the march. They’d made a banner to take to the march and were eager to unfurl it at the Mug and to have a few drinks. I was enough of a joiner for that, at least.

It was early evening, there were maybe a dozen or so of us gay and lesbian students, and on the other side of the dance floor, there was a group of straight students having drinks. The drinking age was 18 back then. I didn’t know any of the straight kids and barely even noticed them at first. At some point, one of my gay friends dared me to write something about the march on the chalkboard. It sounds so tame now, but I was, and am, a scaredy-cat. I hesitated, but I was almost as scared of their reaction if I let on how uncomfortable I was about being so publicly gay.

The chalkboard already said, “Happy Saturday Night at the Mug,” so I went up and wrote the word “gay.” I know—inspired, right? Well, I was pretty pleased with it, reading it back: “Happy Gay Night at the Mug.” All the gay kids cheered and I went back to my seat and my small glass of beer.

Then one of the straight kids walked up to the chalkboard and ran his hand across the word “gay,” erasing it. The straight kids cheered. My gay friends looked at me like, you can’t let that go. And I didn’t. I walked back up to the chalkboard and wrote “gay” again. The gay kids cheered again. I was still standing there when the straight kid came back and stood right in front of me. Right up in my face, he said, “Are you gay?” And I said, “What’s it to you?” I could hardly breathe. He ran his hand across the chalkboard and smeared everything into oblivion.

It’s hard to reconstruct for you the terror of what today seems like a kind of dumb kind of homophobic gesture. But back then, for any gay man who was called out in a straight bar, there was a good chance of getting a serious beating—something I had managed to avoid so far.

The straight kid looked at me as if he dared me to do something. So I slugged him. Hard. So hard that he landed on his back as blood ran out of his nose and down his chin.

Alright, wait, sorry. I didn’t. I didn’t hit him, and thankfully, he didn’t hit me. This was Vassar. Vassar men, even the straight ones, didn’t have fistfights. But I’ve fantasized about slugging him ever since.

In the real version of events, I can’t remember now whether I rewrote “Happy Gay Night at the Mug” on the board, or whether the straight guy and I just retreated to our respective tables for the two groups to do shadow battle with frosty stares. I do know that I’ve replayed this scene over in my head so many times, sometimes with my fantasy knockout punch inserted, that the whole movie’s gotten kind of muddled.

In the immediate aftermath of the march, there was more disagreement—over how many people were there. The official tally was a magical shrinking tally. As reported in the New York Times, “The United States Park Police first put the number at 75,000 but later said between 25,000 and 50,000 showed up.” March organizers were sure it was more, and they pointed to a history of official sources undercounting gay crowds. It’s a neat way of undermining mass movements, to portray them as not having much… mass.

I’m gonna go with Joyce Hunter’s number.

———

JH: Well over a hundred thousand people were there. And of course they wanted to say there was less. You know, they like to banter and have debates about how many people really showed up. But the truth of the matter, there was over a hundred thousand people.

———

EM Narration: Those opposing the march had worried it would be a dud and that it would damage the movement. It certainly wasn’t that.

———

JH: Do you wanna know something? And this is something that Steve and I are very proud of, is that many people from different states, while organizing for this march, created organizations and coalitions where there never was a gay group before. So that was one of the wonderful things to come out of the march.

EM: Did it live up to your expectations?

JH: Yeah, but you can always do better, you know.

EM: What would you, what would you have done better?

JH: Have a million people there.

———

EM Narration: You can always do better. At every step, there are paths not taken, possibilities left unexplored, and regrets. That’s the thing about digging into the past: it can be painful. This season we’ve revisited the repeated failures to pass a gay rights bill in New York City, Anita Bryant’s hateful campaign, or even my difficult experiences with Reverend Mullen.

But facing our past, the good and the bad, facing our failures alongside our triumphs, is the only way we move forward personally and collectively. And it can take years, or longer, for the results to pan out. The 1979 march is largely forgotten, but it made such vital contributions to the movement. As Joyce said, organizations sprang up where there had been none. Joyce met Damien Martin and Emery Hetrick through organizing the march, spawning the Institute for the Protection of Lesbian and Gay Youth, now known as HMI, and later the Harvey Milk High School. The march also helped propel some of the newer organizations to real national prominence. For example, PFLAG underwent a nationwide expansion after the march.

Joyce and I were on very different paths—she’s almost 20 years older than I am. We came of age in different decades but we both came out in the 1970s. A decade that shaped us, and the movement. Joyce now has a lifetime of activism behind her. I was never comfortable in that role or using that title. While Joyce drove the movement forward, I’ve found my life’s work to be chronicling it. Gathering and sharing our stories has been the honor of my life.

Through my work, I’ve had the privilege to meet and befriend people like Joyce, who have continued to inspire me. To challenge me. And to show me a fundamental truth: we are greater than the sum of our parts. Individuals like Joyce Hunter and Harvey Milk and Bebe Scarpi and Morty Manford were crucial to our progress, but the army of lovers that showed up on the streets of Washington, D.C., in October 1979, the millions of LGBTQ people supporting one another and organizing to defend our rights today, show how we are everywhere and we are stronger together.

Even though Joyce and I have played different roles in our work, I think there’s a message that a new generation of young people can take from our lives and experiences: the fight never ends, the work can be—and is—often exhausting and frustrating, but the people you stand with and the joy of community are what make life rich and gratifying. So, while I regret not getting on that bus to Washington in 1979, and really wish I’d punched that guy at the Mug, I’m pretty happy with how it all turned out in the end. And I’m not done yet. Neither is Joyce.

———

This season of Making Gay History was produced and written by me, Eric Marcus, and Making Gay History’s founding editor, Sara Burningham, with archival research and production assistance from Brian Ferree and additional archival research from Tyler Albertario. Special thanks to interviewer-slash-oral historian Shane O’Neill. Our studio engineers for this episode were Katherine Cook and Charles de Montebello. “Coming of Age During the 1970s” was mixed and sound designed by Anne Pope.

This season of Making Gay History was recorded at CDM Sound Studios. Our theme music and additional scoring were composed by Fritz Myers. Our new theme features flautist Anna Urrey.

Many thanks to our hard-working crew at Making Gay History, including deputy director Inge De Taeye, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. We had additional help from Fred Maxon, Rich Gordon, and Phil Frost.

Thank you as well to the New York Public Library Manuscripts and Archives Division for their ongoing assistance. We’re grateful to Adam Ciesielski and Jok Church for their recorded album of the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. And to the online repository QueerMusicHeritage.com, which provided the digitized album. Also, thank you to the Pacifica Radio Archives for access to their recordings of the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

Thanks also to the Fruit Punch Collective and KPFA for their recordings of the White Night riots, also from the Pacifica Radio Archives. And to KPIX TV for their brief clip of Diane Feinstein announcing the assassination of Harvey Milk and San Francisco Mayor George Moscone.

Making Gay History is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Calamus Foundation, and Christopher Street Financial. We’re deeply grateful to Patrick Hinds and Steve Tipton for their two-year grant in support of Making Gay History’s mission to bring LGBTQ history to life through the voices of the people who lived it.

To learn more about the people and stories we’ve featured over the past six years, please visit makinggayhistory.com where you’ll find links to additional information, archival photos, as well as full transcripts for all our episodes.

———

I’ve got one more story to share before saying goodbye until our next season of Making Gay History. And it’s about Jim, my summer of 1978 boyfriend who worked at the White House and introduced me to Midge Costanza.

After I graduated from Vassar in May 1980, I went to work for Tauck Tours as a tour director and was assigned to a West Coast tour even though I’d never been west of New Jersey—15 days, 14 nights, 11 hotels, 44 passengers on a Greyhound bus from San Francisco, California, to Calgary, Alberta, by way of Vancouver, B.C. And then back. So that was how I found myself at a loose end on a day off in San Francisco the weekend of the 1980 pride march. It was only two years since bumping into Midge in the White House colonnade with Jim, but a lot had changed for him since then. By the end of the 1970s, things were not looking good for President Carter’s hopes for reelection. Jim left his job at the White House as an assistant to the president. He was crushed under the burden of 18-hour days, and the constraints of being gay in an entirely straight-seeming workplace. He had just turned 30 and he went West.

He moved to San Francisco, to Castro Street—the heart of the gayest neighborhood in the gayest city in America—and he made a career switch. Jim became a stripper. He told me at the time, the main thing that changed for him at work was that instead of putting on a suit in the morning, he took it off in the evening. He played the role of “young businessman” at a strip club aimed at women. Kind of Chippendale-ish. It was a very unlikely transition. I certainly never would have predicted it. Not in my wildest. I liked him in a business suit.

When I called Jim to let him know that I was going to be in town on pride weekend, he invited me to go to the march with him and his boyfriend. They offered to pick me up in front of my hotel. What to wear to a pride march when you’ve packed for tour-guiding blue-chip tours for blue-haired ladies? I dressed in my usual khakis, blue button-down shirt, and penny loafers.

I walked down the hotel steps and spied Jim and his boyfriend in tight tank tops sitting in a red Chevy Impala convertible with the top down, and they greeted me with wild cheers. I froze and checked that none of my passengers were around. Jim and his boyfriend would have blown my cover. I was back in the closet for work and even carried around a photo of my freshman year girlfriend to show passengers who were eager to fix me up with their granddaughters.

I just about leapt into the backseat of the car hoping not to be seen. We parked near Market Street and stood on a corner watching the parade go by. I’ve rarely felt more out of place than that afternoon. Thankfully we weren’t there for too long. After an hour or so we went back to Jim’s place on Castro Street and went up to the roof, where he and his boyfriend worked on their tans. Jim’s body never saw the sun when he worked at the White House—the last time I’d seen him naked he was so white he was almost translucent—and now he was deeply tanned. With no tan line. Jim said it was a requirement of his new job. We made out for a while, and I figured if his boyfriend didn’t mind, who was I to argue?

Jim and I fell out of touch after that memorable afternoon. The next time I called, his phone number no longer worked and there was no forwarding number. During the early years of the AIDS crisis, plenty of people simply disappeared and I just assumed that Jim had died from AIDS. Over the years, I’ve tried to find out what happened to him, and came up with nothing. And then as I was finishing up work on this episode, I decided to make a bigger effort. So with the help of crackerjack researchers Tyler Albertario and Fred Maxon, we found one of Jim’s friends and a former boyfriend from the 1980s. And this is, in brief, what we learned from them.

Not long after I last saw Jim, he took a job doing marketing for the national gay magazine The Advocate. Jim met his boyfriend Phil in 1984 and together they moved south of San Francisco to San Mateo. Phil told me that Jim had shared with him early in their relationship that he’d been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and Phil recalled that Jim wasn’t always consistent in taking his prescribed medication. In 1987, after waves of Jim’s ups and downs, their relationship reached the breaking point and they separated. Jim stayed in the Bay Area until 1993 and then moved back to western Pennsylvania to live with his parents, and by then he’d been diagnosed with HIV. His friends were concerned about the move, because they worried he wouldn’t get good health care.

That was the last any of Jim’s friends heard from him until Phil got a call in May of 1994 from Jim’s mother. Jim was dead. He’d killed himself. James Harold Mayer died on May 8, 1994. He was 45 years old. May he rest in peace.

“Coming of Age During the 1970s” is a production of Making Gay History.

I’m Eric Marcus. Thanks for listening. So long, until next time.

###