Coming of Age During the 1970s — Chapter Five: Thank You, Anita

Anita Bryant singing at the 1978 Southern Baptist Convention in Atlanta, Georgia. Credit: Ken Hawkins/Alamy.

Anita Bryant singing at the 1978 Southern Baptist Convention in Atlanta, Georgia. Credit: Ken Hawkins/Alamy.Episode Notes

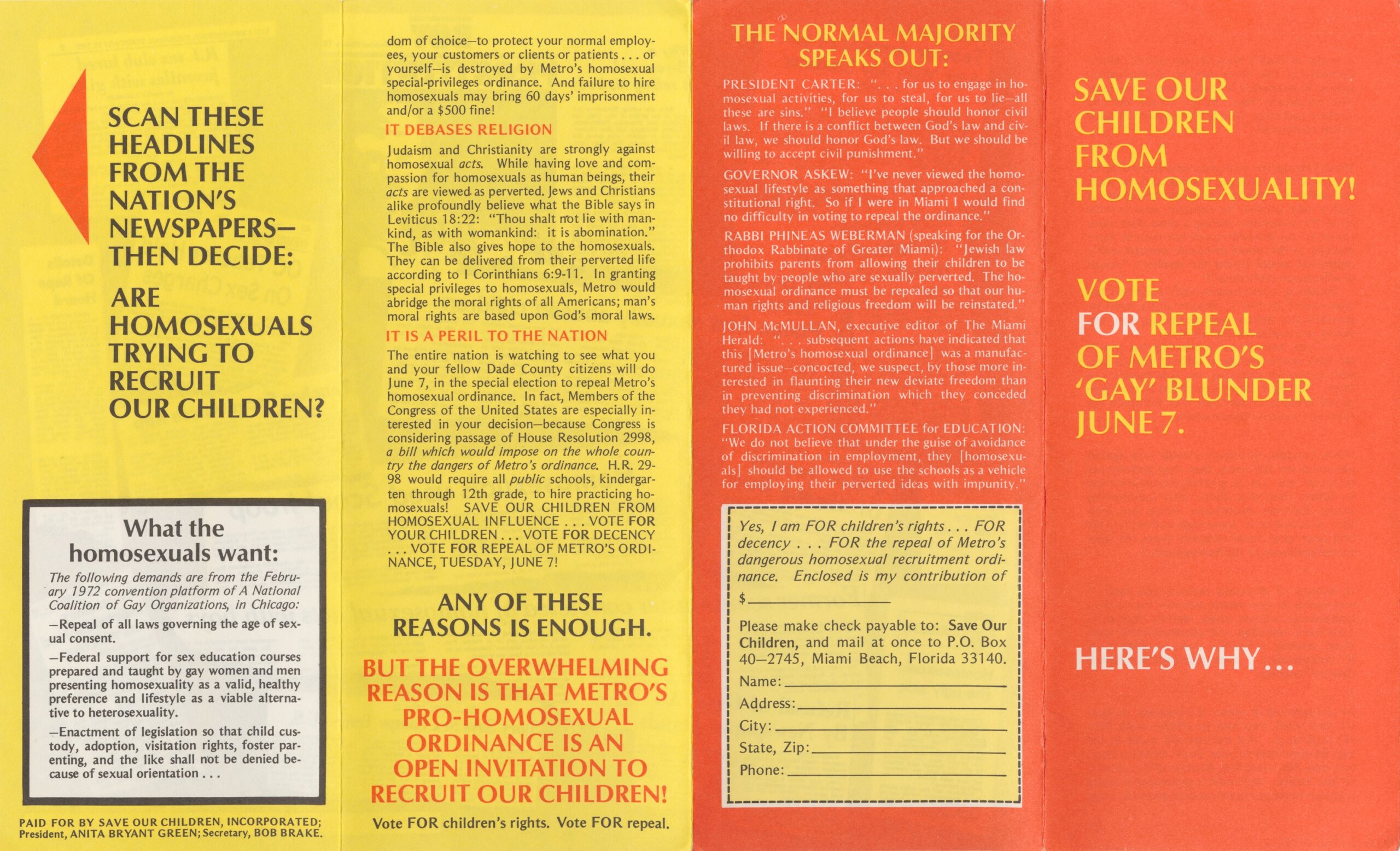

Eric gets an A on his freshman sociology paper, “Marginal Man: The Alcoholic and the Homosexual.” But his sunny predictions for the future of the gay rights movement are met with skepticism from his professor. Mere weeks later, Anita Bryant launches her anti-gay “Save Our Children” campaign.

Episode first published June 8, 2023.

———

Learn more about some of the topics and people discussed in the episode by exploring the links below.

Earliest citywide anti-discrimination ordinances in the United States:

- Likely the first in the nation: East Lansing, Michigan, 1972: “East Lansing Marks 40th Anniversary of Gay Rights Ordinance” (WKAR Public Media, March 6, 2012).

- Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1972: history of LGBTQ activism in Ann Arbor (Lauren Slagter, MLive).

- St. Paul, Minnesota, 1973; repealed 1978: “Law on Homosexuals Repealed in St. Paul” (New York Times, April 26, 1978).

- Washington, D.C., 1973: “Gay Rights Didn’t Alter D.C.” (Washington Post, May 22, 1977).

- Columbus, Ohio, 1974 (a more limited version than the city council originally passed in 1973 after a gubernatorial veto): history of gay rights in Columbus, a presentation by Prof. Douglas Whaley (YouTube).

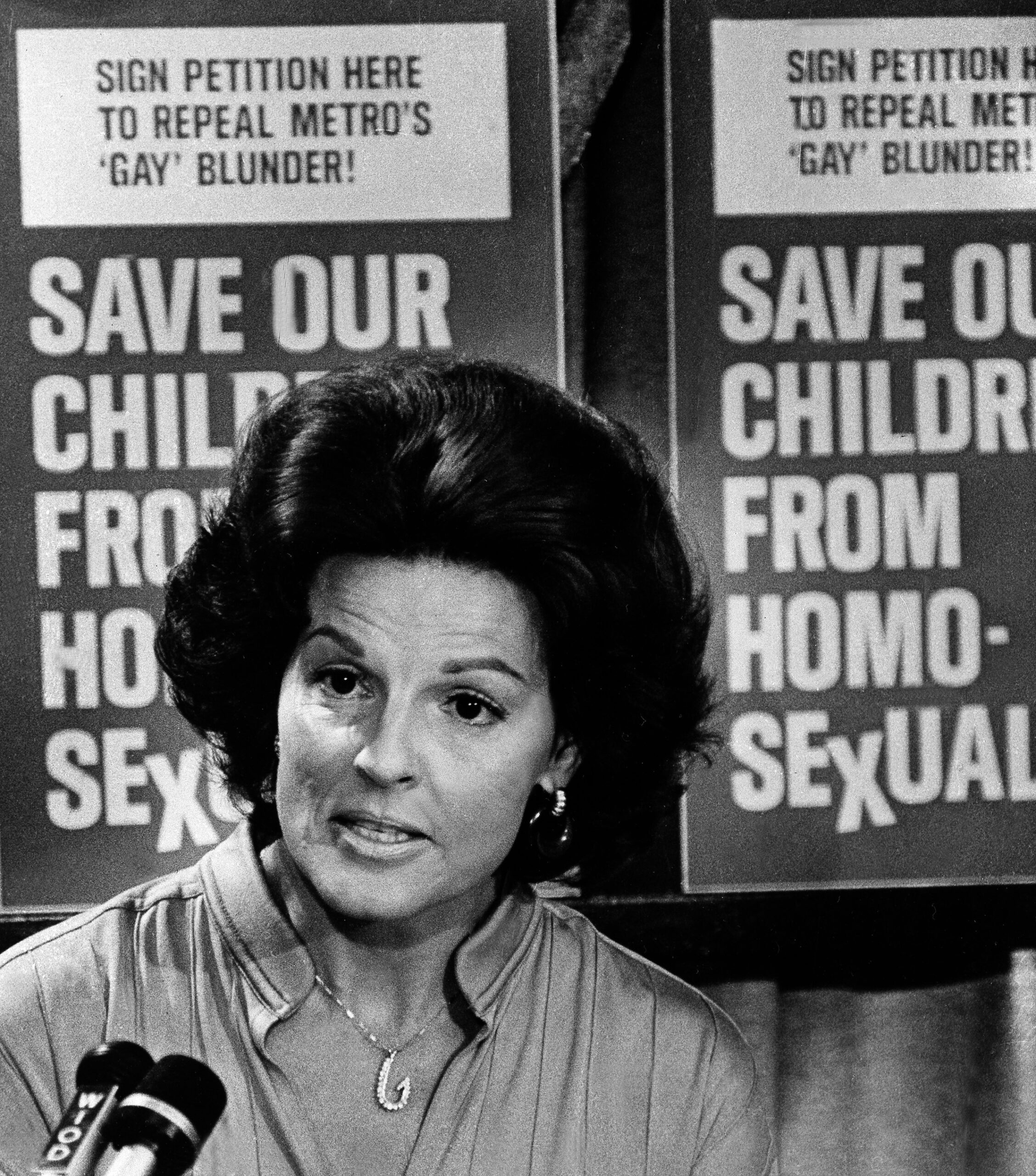

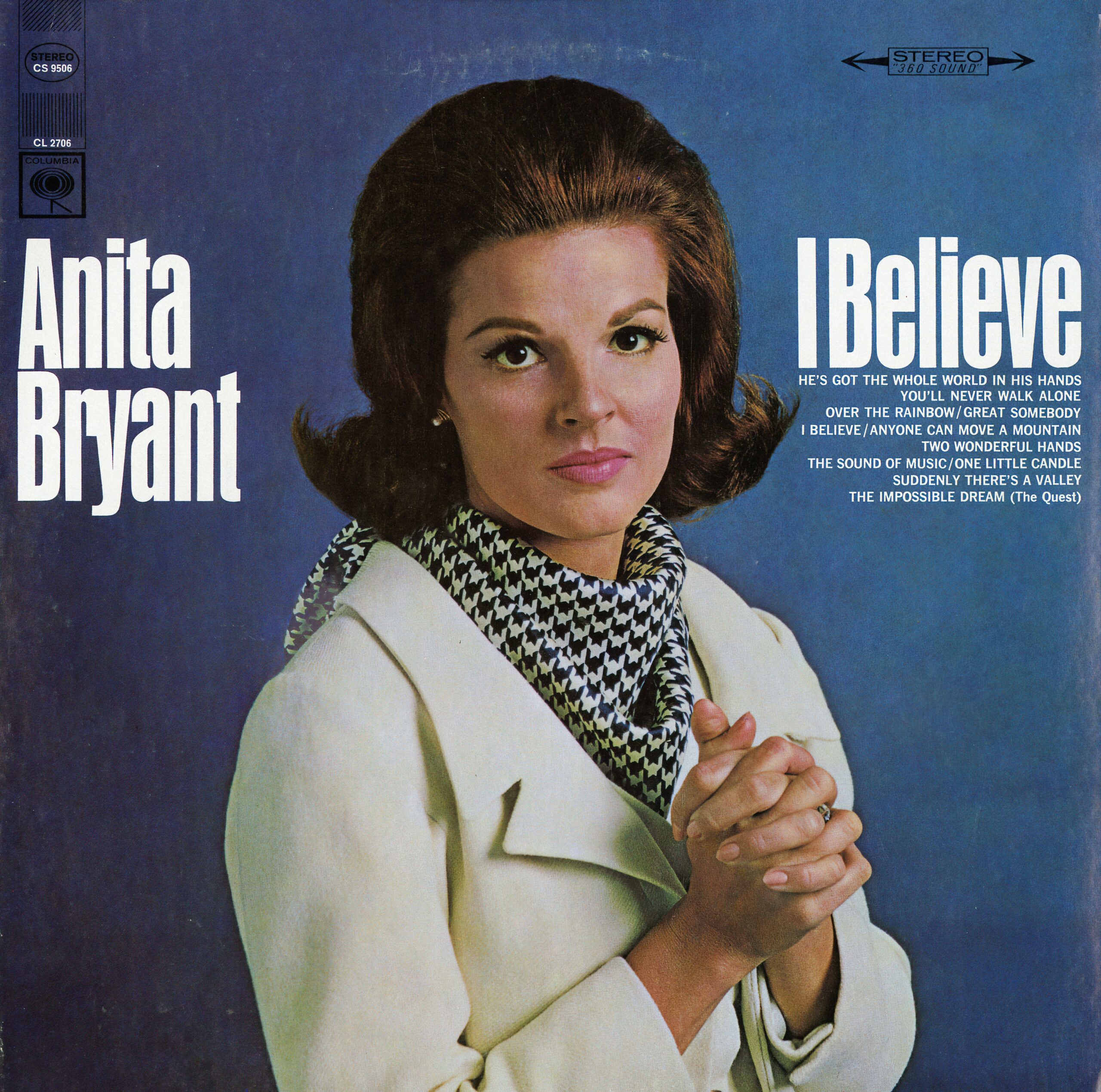

Anita Bryant, Save Our Children campaign, legacy:

- Brief biography of Anita Bryant (Nikolai Endres, GLBTQ Archives).

- “1977: Anita Bryant’s War on Gay Rights,” Slate’s One Year podcast.

- “The Long Road to Employment Non-Discrimination for LGBTQ People in Miami,” brief historical context for the Bryant campaign (Julio Capó, Jr., ACLU Florida).

- Historical video footage of the Miami-Dade gay rights ordinance controversy, including interviews with Bob Kunst, Leonard Matlovich, and other activists (SuchIsLifeVideos/YouTube).

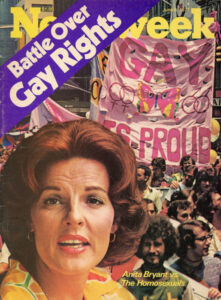

- Contemporary mainstream press coverage: “Battle over Gay Rights,” Newsweek, June 6, 1977; “Enough! Enough! Enough!” Time, June 20, 1977.

- CNN segment, “How New Anti-LGBTQ Laws Echo an Infamous Conservative Activist’s Campaign from 1977” (Reality Check with John Avlon, July 1, 2022).

- “How 1970s Christian Crusader Anita Bryant Helped Spawn Florida’s LGBTQ Culture War” (Jillian Eugenios, NBC News, April 13, 2022).

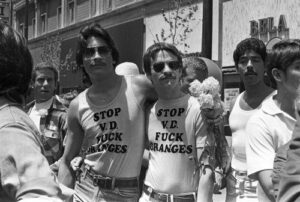

LGBTQ cultural responses to Anita Bryant:

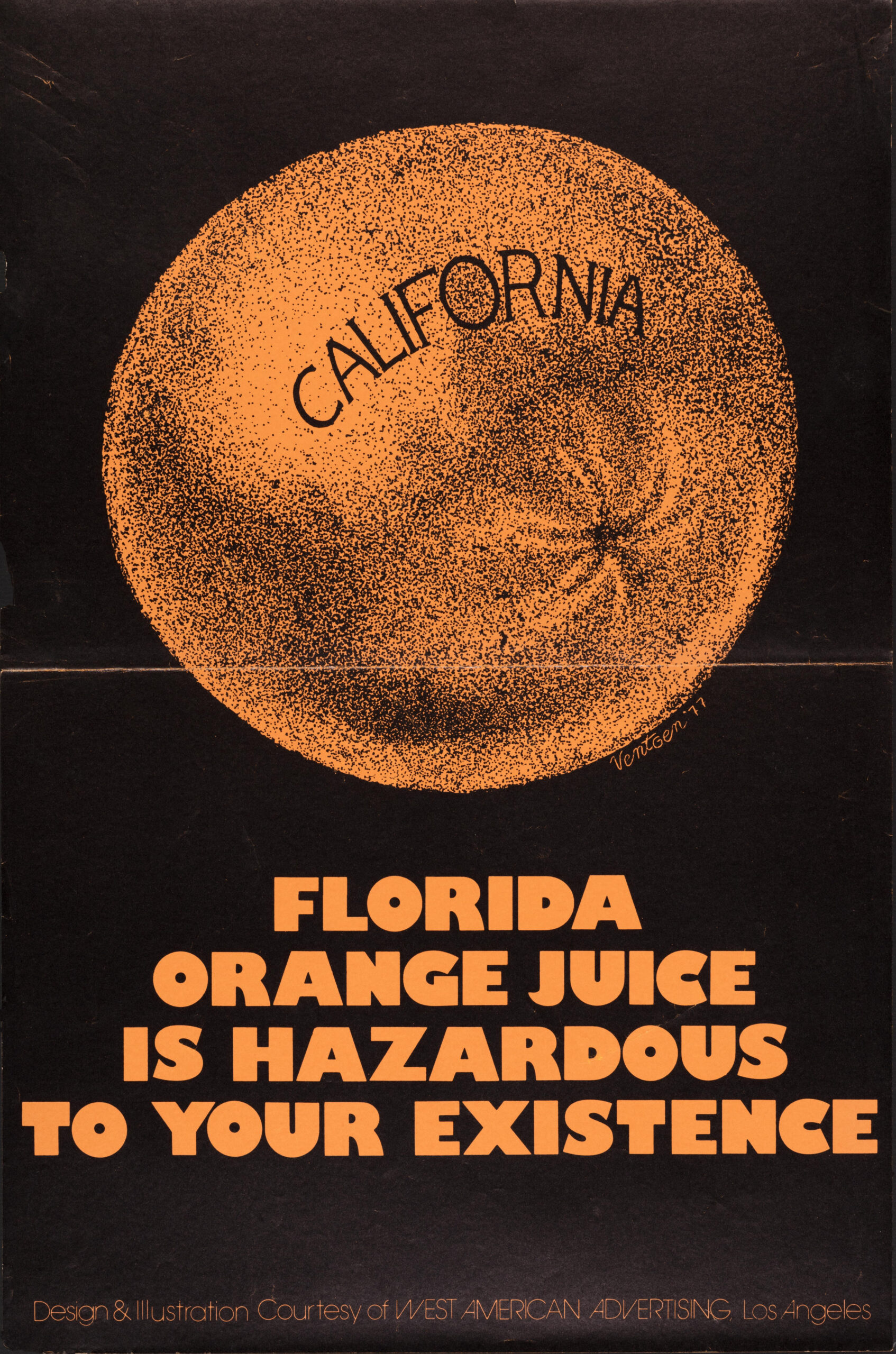

- Music: Olivia Records album Lesbian Concentrate (which includes “Don’t Pray for Me” by Linda Tillery and songs by Meg Christian, Cris Williamson, and more); “Thank You Anita” by Charlie King; “Ode to Anita” by Michelle Faithe; “What Are We Going to Do about Anita?” by Casse Culver; “Don’t Drink the Orange Juice” by Rod McKuen; “Squeeze a Fruit for Anita” by Anni O’Brien & Rosey Carter; “Anita OJ” by Tom Paxton; “[Lord Knows] I Don’t Need Anita” by The Four Swallows; “Gay Rock for Anita” by Paul Vincent.

- Buttons, posters, pamphlets: “Anita Sucks [Oranges]” button; supportive message from Holland T-shirt; orange juice boycott poster; “Save Our Children from Anita Bryant” poster; Bryant as the Wicked Witch of the West graphic; “Human rights molester” Bryant caricature.

Charlie Brydon:

- “Charlie Brydon, Pioneering Seattle LGBTQ+ Activist and Entrepreneur, Dies at 81” (Seattle Times, February 27, 2021).

- “The Gay Rights Movement and the City of Seattle during the 1970s,” digital exhibit (Seattle Municipal Archives).

Harvey Milk and the Briggs Initiative:

- Brief biography of Harvey Milk (Harvey Milk Foundation).

- Correcting a common misconception: “Meet the Lesbian Who Made Political History Years before Harvey Milk” about Ann Arbor, Michigan, city council member Kathy Kozachenko, the first out person elected to political office in the U.S. (Julie Compton, NBC News, April 2, 2020).

- Animated video, “Harvey Milk’s Radical Vision of Equality,” written by Lillian Faderman (TED-Ed/YouTube).

- Primary source set about Milk (GLBT Historical Society).

- Pat Rocco video of Milk railing against Anita Bryant and the Briggs Initiative at the 1978 Gay Pride Parade in Los Angeles (UCLA Film & Television Archive/YouTube).

- 1978 radio interview in which Milk discusses Bryant and the Briggs Initiative (Pacifica Radio Archive).

- “The Briggs Initiative: Remembering a Crucial Moment in Gay History” by Trudy Ring (The Advocate, August 31, 2018).

- 1978 video of Milk debating John Briggs (KPIX-TV/Bay Area Television Archive).

- Primary sources about the Briggs Initiative (GLBT Historical Society).

Coming out to one’s parents:

- Is It a Choice? Answers to the Most Frequently Asked Questions about Gay & Lesbian People by Eric Marcus (HarperCollins, 2005 [3rd ed.]).

Album cover and back of the 1977 Olivia Records release “Lesbian Concentrate,” which was produced in response to Anita Bryant’s anti-gay crusade. Credit: Olivia Records via JD Doyle, QueerMusicHeritage.com.

———

Song Credit

”Don’t Pray for Me”

Words and music by Mary D. Watkins

Performed by Linda Tillery

Courtesy of Mary D. Watkins and Olivia Records

Used by permission; all rights reserved

The version of “Don’t Pray for Me” used in the episode was featured on Linda Tillery’s self-titled solo album (Olivia Records, 1977). Listen to the album in its entirety here and learn more about Tillery courtesy of this Queer Music Heritage webpage.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: By the time I finished my first year of college, I couldn’t exactly fool myself into thinking I wasn’t gay, even though it wasn’t what I wanted for my life. I’d been through enough men by that point to set aside any doubts that this was who I was and that a wife and kids were not in my future, but I had no clear image of what my future would hold—what life might look like for this gay man. If there were role models out there for the kind of life I might want to lead, I hadn’t seen them.

In April 1977, toward the end of that first year, I turned a sociology paper into a personal fact-finding mission. Under the cover of research, I spent hours in the Vassar library pouring over books about gay people. I wasn’t ready to be out in class, so I masked my subject matter interest by adding a decoy subject. I named the paper “Marginal Man: The Alcoholic and the Homosexual.”

———

Prof. Eileen Leonard: My name is Eileen Leonard, and, uh, I was a professor of sociology at Vassar, and I worked there for 44 years. I started in 1975.

Eric Marcus: So you arrived one year before I did.

EL: Yes.

EM: I don’t expect you to remember me from the class. It was Intro Sociology in the spring of 1977.

EL: Right. In fact, I, I do remember you from that class. I think I have a clearer memory of the students that I had initially than I do as the decades went by.

EM: I can’t believe we’re having this conversation all these years later. So let’s talk about my paper from April of 1977.

EL: Right.

EM: I may seem like a crazy person, but I saved all of my papers from Vassar College. And I didn’t think I was a particularly good writer, but reading this paper over, I thought, well, for 18 years old it was pretty good.

EL: Yes.Yeah.

EM: I was sort of out, but, but sort of not. Actually by then I’d broken up with my girlfriend. I had a boyfriend. It was a very confusing year. I was really interested in writing about the homosexual, not the alcoholic. I went to the Vassar library to look in the card catalog, and a lot of what I found was terrible. But a lot was also very interesting. And the reason I included alcoholics is—I thought if I only wrote about homosexuals, that you would figure out I was gay. Um, and I found this concept of “marginal men”—it’s a category, which I learned in sociology—which, uh, allowed me to do the paper.

So, um, I’m gonna read the conclusion to the paper. It’s a little embarrassing because it’s just—I’m reading my 18-year-old self. This is just the last paragraph. “If present trends in the legitimization of homosexuality continue, then surely there is hope for the, perhaps reluctant, acceptance of homosexuality into American culture. Maybe then, homosexuality can be removed from the list of marginal men so that the list reads one less member than it does today. Alcoholics,” exclamation point, “Homosexuals,” exclamation point, “Marginal,” question mark. “That’s up to you,” and then I have—one, two, three, four, five, six, seven—eight exclamation points.

You gave me an A.

EL: Yes.

EM: I’m not sure I would have. So if you don’t mind reading your handwritten comments at the end of the paper.

EL: I’d be happy to do that. And now I’m reading my 28-year-old self commenting. “Your paper is well done. You should have elaborated on the concept of marginal man in more detail at the beginning of the paper, but what’s here is well written and well organized. You point out how difficult it is to be marginal in society—this is clearly the case for all kinds of ‘deviants.’ I’m not sure I share your optimism about the future status of homosexualties [sic]. There is still a long way to go—and always a possibility of regression.”

Marginal Men 4-18-77Eric Marcus’s freshman sociology paper, “Marginal Man: The Alcoholic and the Homosexual.”

———

EM Narration: I’m Eric Marcus. This is “Coming of Age During the 1970s.” Chapter five: “Thank you, Anita.”

———

Anita Bryant: Time to get up, kids. You, too, orange bird…

———

EM: In my family, we discovered real orange juice a little late because we didn’t have money. We were basically working-class poor. The first time I had fresh squeezed orange juice, it was a special, special treat. I was so shocked because it didn’t even vaguely resemble the orange stuff that came out of a carton, which—they may have called it orange juice, but it didn’t taste that way.

So I knew of Anita Bryant as the orange juice lady. And I recall their slogan was something to the effect, “A day without orange juice is like a day without sunshine.”

So that’s how I knew Anita Bryant.

———

AB: [singing] … serve it generously / from the Florida sunshine tree…

———

EM Narration: While New York City tried and failed, and tried and failed, and tried and failed… to pass a gay rights bill, dozens of places hit it first time lucky—all over the country, from Washington, D.C., to Chicago to Kansas City, Columbus, Ohio, to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Minneapolis, and Bloomington, Indiana. By the end of 1976, 37 jurisdictions had legislated in some way to protect gay people from discrimination.

But my sociology professor was right. The backlash was coming. On January 18, 1977, Miami-Dade County held a hearing to amend its human rights ordinance to forbid discrimination based on “sexual or affectional preference.” Like New York, Florida’s sodomy law had yet to be repealed, so this wasn’t about legalizing physical relationships between two people of the same sex. This was about protecting people from being fired or denied housing or discriminated against in public accommodations because of their sexual orientation.

The hearing was packed. Church folks, gay rights activists, and toward the end, a celebrity. The orange juice lady got up to testify. A one-time beauty queen—a former Miss Oklahoma—she said she was speaking as a wife and mother. Sounding as though she was about to cry, she said the proposed amendment would cause discrimination against her and other Christians. They were the real victims.

———

Anita Bryant: I believe I have that right, that I can and do say no to a very serious moral issue that would violate my rights and the rights of all the decent and morally upstanding citizens regardless of their race or religion.

———

EM Narration: The final vote was five in favor, three against. The ordinance passed. Gay people celebrated. But those who opposed it got busy.

———

Unidentified Reporter: The ordinance becomes law in 10 days, but a religious group headed by Anita Bryant said it will definitely begin a petition drive to repeal the law.

———

EM Narration: Bryant and her supporters gathered six times more signatures than needed to put repeal on the ballot. The Dade County Commission voted to call a special election on June 7.

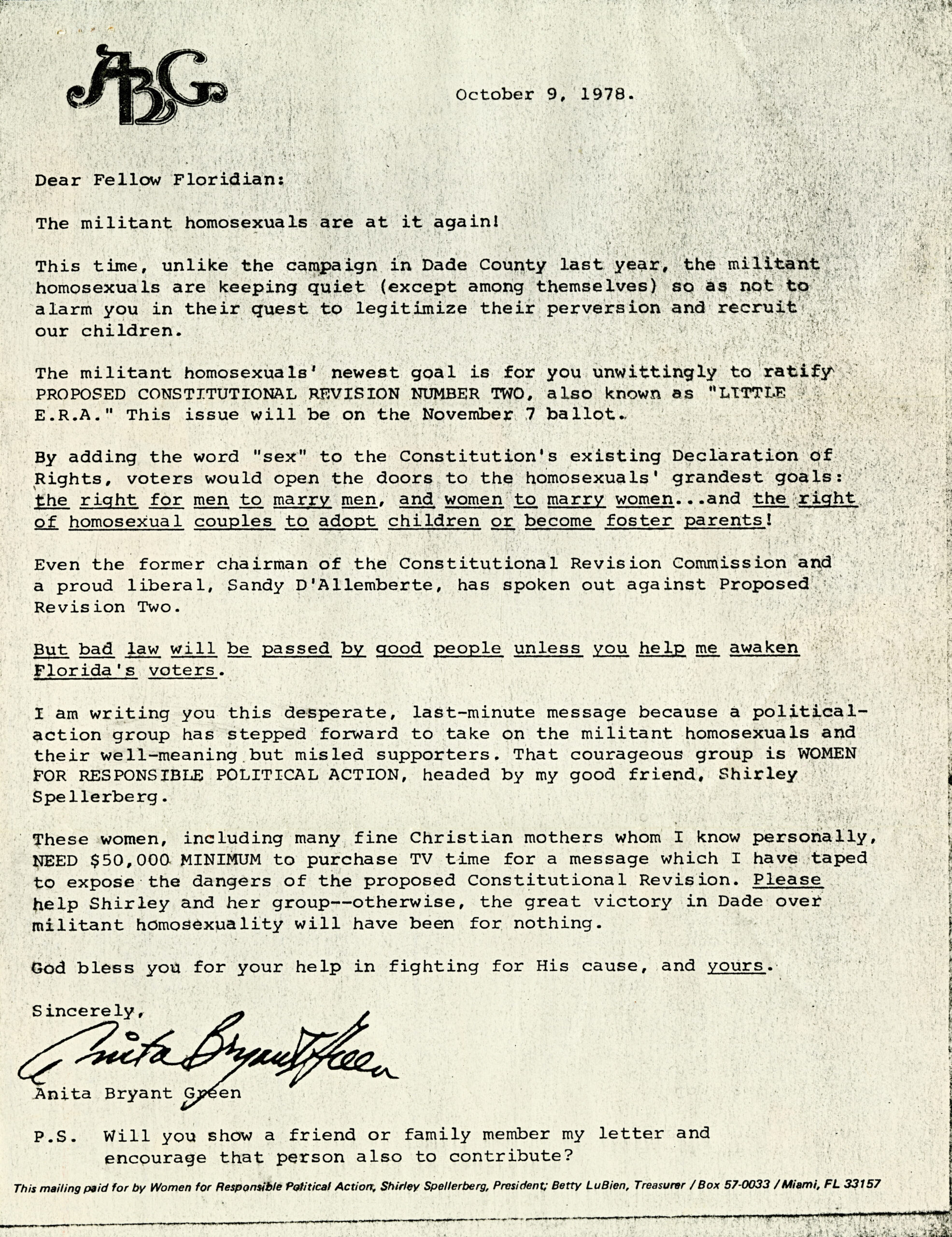

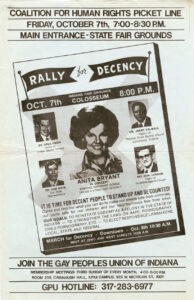

Repealing ordinances became a rallying cry for the Christian right. Not just in Florida, but around the country. The Save Our Children campaign had been born. The brewing backlash had broken through with the perfect brand ambassador: Anita Bryant.

———

AB: [singing] … in my life has been wrought / Since Jesus came into my heart…

———

AB: … just biologically, that God made mothers so that we could reproduce, homosexuals cannot reproduce biologically but they have to reproduce by recruiting our children.

———

Voice-over: Summer 1977, Queens, New York. Jamaica Estates. A skinny Tudor Revival house on a leafy street.

EM: In, it was probably July, I was back from college. Living at home, which was a little tense to start with because my mother and I had not been getting along since my, since I was 16, I think. Um, before I left for college, she would often say, “I can’t wait for you to leave,” and I would say, “I can’t wait to leave, too.” Um, typical teenage stuff, but also I was gay and coming to terms with it and was just angry all the time. And depressed.

Um, my mother and I had this complex relationship that was in no small part related to the fact that my father and mother split up when I was 10, and my father then killed himself when I was 12, and my mother depended upon me like a partner as opposed to treating me like her child. I knew way too much, but I also wasn’t in control: when it was convenient for her, I was then the child again, and she made decisions even if I thought they were the wrong decisions, and I deeply resented some of those things.

Voice-over: Interior, kitchen, it’s morning.

EM: It was really an ugly kitchen that had been done over by the people who lived there before. It was dark, uh, uh, paneling, faux wood. Um, and we had a Formica kitchen dinette set.

Voice-over: The table is pockmarked, damaged years before when Eric’s mother flew into a rage and hacked at it with a spatula, sending chips of Formica flying.

EM: I remember at breakfast one morning picking up—I don’t remember if we subscribed to Time magazine or Newsweek—I remember holding the magazine, and Anita Bryant was on the cover. And, um, I was in a rage and I said that these were all lies.

Who is she? Who is Anita Bryant?

This is horrible. This is, uh, not true about gay people. And I recall being wildly outraged, uncontrollably angry that people were, were referring to people like me as recruiters.

Why is she saying this in print? Why is she leading this campaign?

Now they use the word groomer. It’s just, you know, same product, different flavor. Anita Bryant so enraged me because I felt like she was reinforcing all the things that, bad things that people thought about us, and also all the bad things I thought about myself.

We were sick, sinful, perverted, um, and destined to lead a life of ruin. Or, as, uh, that book, uh, Everything You Wanted to Know about Sex But Were Afraid to Ask said about homosexuals: that we were destined to have furtive relationships and hide out in bushes and offer candy to small children.

So even though I came to understand that that wasn’t who I was and that these were lies, it was painful and enraging to hear someone like Anita Bryant speak so fervently about how awful we were and that we were a danger to children.

And I remember thinking, you’re a danger to children. I’m not the danger to children because you are harming people like me.

I will never fucking drink orange juice again.

My mother did not engage me in conversation at that point other than to say, “Why are you so upset? I don’t understand why you’re so concerned about this.” And then I realized I’m, I might have tipped my hand. I was closeted. That was a very hard thing for me. I’m a terrible liar, so I wasn’t consciously dropping hints. And backed off.

———

EM Narration: Anita Bryant’s Save Our Children campaign was the first organized opposition to the gay rights movement. It was well-organized, well-funded, and in a way it illustrated how far we’d come, that gay liberation organizing provoked such a response. And it, in turn, provoked a response from us. LGBTQ people who heard Bryant’s language of bigotry and hate realized that progress isn’t inevitable or a straight line.

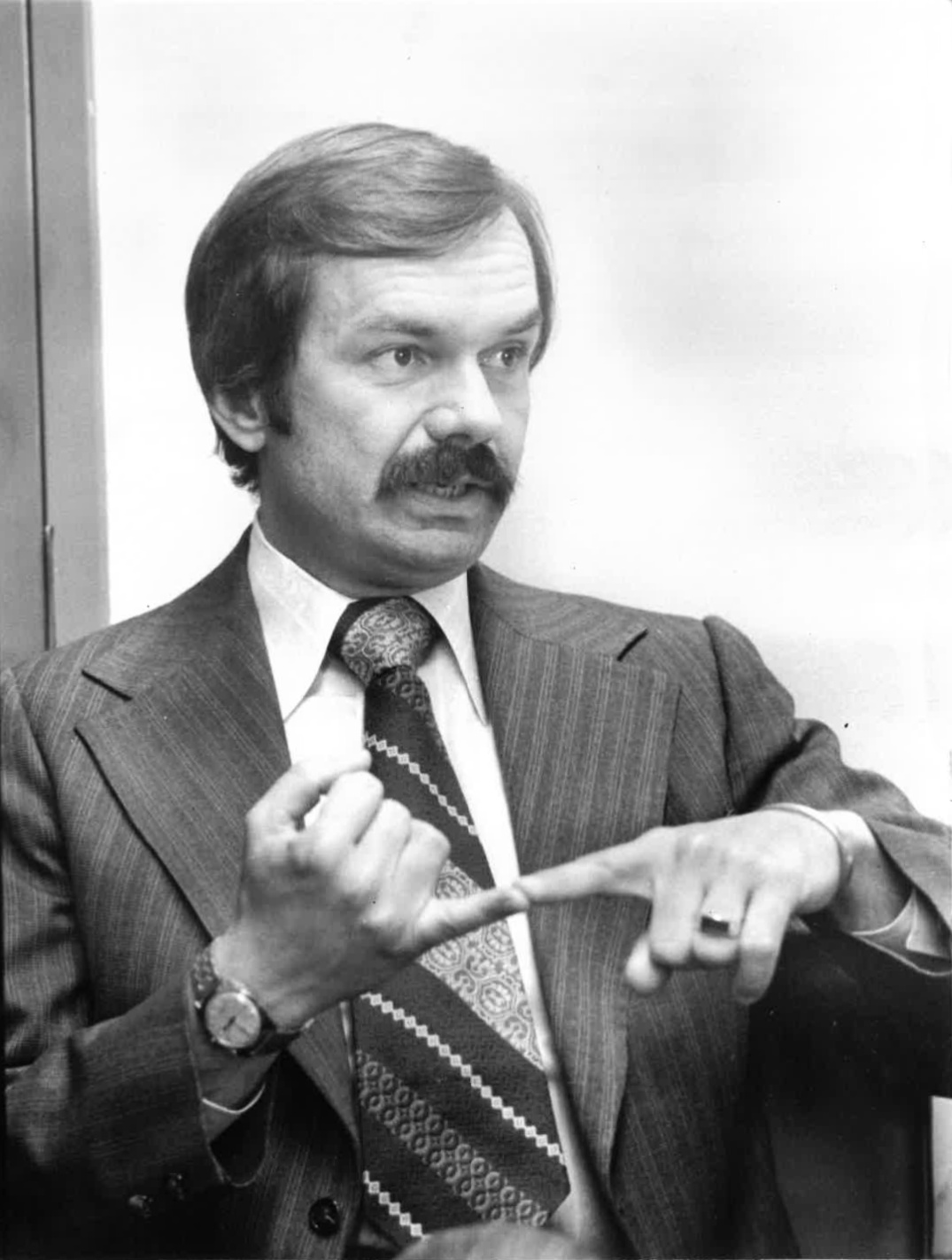

Bob Kunst was one of the key gay activists in Miami-Dade—an unabashed radical. Here he is, taking on the fundamentalist Christian agenda for what it was: a smear campaign accusing gay people, especially gay men, of being child molestors. Just like in New York City, opponents of Miami’s ordinance focused their messaging on protecting children. Bob Kunst was calling them out.

———

Bob Kunst: Last year, Florida had a hundred thousand child abuse cases, 30,000 which were reported, 1,200 kids literally killed by their own parents. Where was the so-called Save Our Children when we really needed them? The hate and viciousness assaulting this entire community has backfired strongly against the Anita Bryant forces because they haven’t proven their case at all.

Not one incident has happened here since passage of this ordinance January 18, nor in any of the 40 communities that have passed such an ordinance, nor in the two communities—Iowa City, Iowa, and Tucson, Arizona—that have passed theirs since this began. And what is happening with the so-called Save Our Children is that they are asking for the right to discriminate, not only against gay people, but those who practice birth control, have had abortions, who smoke pot, drink alcohol, men and women who live with each other who are not married, et cetera, ad nauseam. In other words, the attack appears to be on everyone who cannot fit their molds, who they cannot control, and who have different affectional and sexual preferences.

Bob Kunst, 1981. Credit: Denver Post via Getty Images.

———

EM Narration: Efforts to repeal anti-discrimination ordinances––inspired by Save Our Children, in some cases sponsored by it––were springing up all over, in places like Wichita, Kansas, St. Paul, Minnesota, and Eugene, Oregon.

In Seattle, Charlie Brydon was aware of the rising tide of reactionary forces. He was a businessman who’d gathered other gay and lesbian business people for networking lunches under the banner of the Dorian Group. His organization was instrumental in passing a nondiscrimination ordinance in Seattle in 1975.

———

EM: Interview with Charles Brydon, Sunday, November 19, 1989, at 12:30 p.m., at the home of Charles Brydon in Seattle, Washington. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

———

EM Narration: Charlie remembers when Anita Bryant first hit his radar.

———

Charlie Brydon: She was singing orange juice commercials. And then she was this former entertainer and she seemed quite benign. And then she does this thing down there and it cau—caused quite a tizzy.

I think people up here largely saw it as… You know, there’s, there’s this attitude of Easterners towards Westerners. Well, there’s also some of that handed back in return. “Only the primitives over there could have had this happen to them.” There was a little arrogance in that, a lot of arrogance in that.

Uh, some money was raised here. Uh, I know one of the Dorian dinners, I think, we even had a general collection and raised a couple thousand dollars. In other words, it was a feeling that it was there, but it wasn’t, you know, an immediate threat to people here.

EM: What was the purpose of raising the money for? Where did it go?

CB: Down to Florida.

———

EM Narration: Gay rights groups around the country were raising money to send to Florida and fund the fight against repeal. Political operatives from San Francisco and New York went down to Miami to pitch in. But as the drumbeats for repeal grew louder in other parts of the country, they still seemed far away from where Charlie was sitting.

———

CB: There was a sense of, well, here in Seattle at least, you know, we’re way beyond that. We’ve got the ordinances, the environment’s so much different. Um, there was, uh, a little sense, a little snobbery probably in, in that.

———

EM Narration: The fight in Miami was taking center stage nationally. Save Our Children lobbied hard to defeat a resolution before Congress—HR 2998—for a nationwide ban on homophobic discrimination in housing, employment, and public accommodations.

In Florida, Save Our Children ran full-page ads in the Miami Herald and the Miami News. According to gay activists, the Herald refused to run ads from groups supporting the nondiscrimination ordinance. And this TV commercial from Save Our Children beamed into Florida homes in the runup to the vote.

———

Ad Voice-over: The Orange Bowl Parade, Miami’s gift to the nation. Wholesome entertainment. But in San Francisco, when they take to the streets, it’s a parade of homosexuals. Men hugging other men, cavorting with little boys.

———

EM Narration: Despite charged rhetoric like that—gay people don’t exist, they flaunt; they don’t march, they cavort—despite the actual words we heard coming out of their actual mouths, those campaigning against equal rights insisted they weren’t coming after gay people. They were just defending children from being “recruited” by us. That really, they loved gay people.

———

AB: I love homosexuals, if you can believe that.

———

EM Narration: Can you hear me rolling my eyes?

———

AB: I love them enough to tell them the truth, because I know that there is hope for the homosexuals. That if they are willing to, uh, turn from, uh, sin the same as any individual, that, uh, that they can be ex-homosexuals—the same as there can be an ex-murderer, an ex-thief, an ex-anybody.

———

EM Narration: On June 7, 1977, Miami-Dade residents voted two to one to repeal the gay rights ordinance. The next day, the New York Times published an op-ed from the co-executive directors of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, Jean O’Leary and Bruce Voeller. It began, “Anita Bryant and her Save Our Children Inc. are doing the 20 million lesbians and gay men in America an enormous favor: they are focusing for the public the nature of the prejudice and discrimination we face.”

The question was, did highlighting the nature of that prejudice and discrimination mean that Florida would be an exception? Or were newly passed ordinances around the country about to topple one by one? Charlie Brydon again.

———

CB: Then it got a little more uncomfortable as that Bryant thing started to spread elsewhere. There was a problem in Den—in Colorado, and then Kansas City and St. Paul. I think the St. Paul thing was, shook a lot of people up.

———

EM Narration: Those drumbeats of regression were sounding much closer to home. When Charlie Brydon picked up the free weekly newspaper in Seattle at the end of June 1977, he almost choked. His face was staring back at him, beside the headline, “Ready when you are, Anita.”

———

CB: I just had a cow at that headline. I raised hell with the editor. I said, “How could you…? I never even said that, and you put it in quotes and put it on the front page.” What a provocative thing to do, it’s very uncharacteristic of me.

EM: And that’s a full-page picture of you on the front page, saying “Ready when you are, Anita.”

CB: Yes. And, like, it couldn’t have been. I never said it.

EM: Oh well. Let’s see. That’s dated, uh, June 29 to July 5, 1977. So this was before the repeal was called for here in Seattle?

CB: Yes.

———

EM Narration: Charlie was angry at that front page because he wanted to take a different approach in Seattle. Instead of provoking, or even loudly responding to the Save Our Children campaign, he wanted to deny them the oxygen of publicity—to ignore them in the hopes they would go away.

After the defeat in Dade County, the blame game was in full swing. Familiar splits and controversies like how radical to be, how provocative, whether to ask nicely or demand loudly, were back on the gay agenda.

And the issue didn’t go away in Seattle. In the spring of 1978, a pair of police officers filed to repeal the city’s gay rights ordinances. They needed to collect 17,000 signatures by August 1 to get it on the November ballot.

———

CB: I just remember, I thought, oh, they’ll never get the signatures. And I kind of, the strategy at the time was to not draw any media attention to the signature gathering issue. What, uh, at that point, in ’77, I had quite, we had, generally the community had some very wonderful political chips. Uh, when this cop filed the, the petitions to gather signatures, they, we immediately formed a very quiet group to begin planning. And most of it was the political brains of the city came together and gave me the advice: don’t do anything that would give media attention to it.

Well, now that immediately put me at odds with the, the radicals who wanted to focus attention on this and, and try and create, I suspect, the feeling that you are a bad person if you sign these petitions. So anyhow, the thing eventually did qualify and we did face that. It was probably the darkest evening of my life, was the day that the news reported that the petitions had been filed and they contained more than adequate signatures to place this thing on the ballot. And, well, I just didn’t know what we would do.

EM: Why was it—was it such a dark day because you didn’t know what direction…?

CB: It was very depressing to see that this thing had actually, was going to descend on Seattle. I mean, what we had seen was a chain of defeats around the country. Uh, why would it be any different here?

———

EM: I don’t think she had a clue that I was, until the moment that she finally asked me if I was gay.

Voice-over: Jamaica Estates, Queens. Summer 1977. The Marcus family home.

EM: Probably within days of the Anita Bryant conversation, um, I was going out—it was early evening—uh, to see a friend of mine. And she asked how he was doing and I said, “You know, I don’t think he’s doing so well. He’s been very depressed. I think he might be gay.” She got suspicious and stopped and paused and said, “Why are you being so casual about that?” And that’s when she, she almost was speaking to herself, she said, “Well, maybe that’s because you’re gay.” And then I said, “See you later, Ma.”

You know, if I could do it over, I would’ve said—and there are no do-overs in this world—I would’ve said, “Let’s sit down and talk about this.” But that’s me, 64-year-old me, talking now. Eighteen-year-old me wanted out of there as fast as I could get out of there.

And she didn’t say, “Stop.” Um, and maybe I said, “Let’s talk about that later.” I don’t recall saying that. I just remember saying goodbye.

And I headed out the door in the kitchen, which went into the garage, and drove to my friend’s house. And, um, I said to Richard, “What am I gonna do? What am I gonna do? Um, my mother thinks I’m gay.” And he knew I was gay. Uh, and I stayed quite late at Richard’s, hoping my mother would be asleep by the time I got home.

And I remember you could, you could roll down the driveway with the car off and the lights off. So I turned into the driveway, rolled down the driveway with the lights off and with the engine off. And I crept back into the house and crept up the stairs. My mom’s bedroom was off the stairs on the second floor; I had a, uh, my bedroom on the third floor. I had to open a door and go up those stairs. I literally crawled up the stairs on all four so that I wouldn’t, the stairs wouldn’t creak and wake my mom up.

But as I got to the landing, I could see my mother’s door was open a crack, and she said, “I want to talk to you.” So, um, and you can only imagine how my heart was pounding at this point, because like any gay kid, or most gay kids, I was terrified of what my mother would say. And I was such a good boy that this was the one incredible stain, that I was gonna dis—uh, that this was just the one incredible stain. I was—I, I had got good grades, I didn’t cause trouble other than being a very cranky kid at that point…

So I went into her bedroom, um, and sat on the bed. She had—she was already in bed. Um, and I don’t remember what she said, interestingly, but I recall saying, “Yes, I’m gay.” And I said, “Do you feel guilty?” Because by this point I had investigated PFLAG, which was once known as Parents, Friends, and Families of Lesbians and Gays. And from my understanding in my research, parents often felt guilty about having, uh, their, having a gay kid, that they saw it as their fault. That was one of the beliefs—uh, uh, aggressive mother, passive father, all of that, that, uh, Freudian bullshit. And she said, “I don’t feel guilty. I’m disappointed.”

Shane O’Neill: Hmm.

EM: Now she might have just as well picked up a knife and stuck it in my heart. And I started crying because there was nothing worse she could have said than she was disappointed.

The last part of our conversation was, um, me telling her that I wanted her to go to PFLAG, and she said she wanted me to go to a psychiatrist. And I assumed she wanted me to go to a psychiatrist because she wanted me to change. I said “No,” and she said “No.” We were both very stubborn. Um, and that was the conversation.

I went back up to my room. Um, it was too late to call anybody. We didn’t have the Internet or texts or any of that, and that was the conversation. That’s how it went. Now I learned later that my mother wanted me to see a psychiatrist because she was fearful that, um, I would kill myself because, um, she recognized me as being depressed, and my father had killed himself a few years prior. So I, I was not appreciative of her concern in that regard.

It was many years before she went to PFLAG, and it was many years before I went to a therapist. Uh, I wish that she had gone to PFLAG earlier, I wish I’d gone to a therapist early. I really needed a therapist, maybe more than she needed PFLAG. Um, and I wish I had handled it differently.

Um, I have written about the ideal way in which young people can share this news with their parents. The ideal way is not to have a parent say, “I think you might be gay,” and then to say, “Bye, Ma, I’m outta here.” Um, but I was scared and I, I mean, I have a lot of compassion for myself at that age. I was 18 years old, so I was doing the best I could in a world that was, that was awfully challenging for young gay people. Um, but I nonetheless was in—incredibly relieved, uh, that, uh, it was gonna be okay.

SO: I would also add not just, not just that you were 18—it’s always hard to be young—and not just that the world, it was challenging, but I think there’s also—if I may editorialize, and you’re getting at this already—I mean, it just sounds like you were two people who ended up really doing the best you could, considering that you were sort of, you were moving without a map, you were going without a guide.

Like, no one had written the books that you have written yet. You couldn’t go online to find out the best way to come out to your parents. I mean, it sounds to me kind of remarkable that, that you’ve, you did the best you could with no guidance. Do you feel that’s accurate?

EM: Yeah, with a little bit of guidance. I’m, I’m thinking that I probably—’cause I knew about PFLAG, I must have looked at some of their material because I knew that parents often felt guilty. I did, uh, I had done my research for, for my, my, uh, social—sociology class for Miss Leonard in the, in, uh, the spring of ’77.

So I, I had more understanding, I think, than most young gay people. But really there, there wasn’t—I couldn’t give my mother Is It a Choice? Questions and Answers about Gay and Lesbian People—or Lesbian and Gay People, I can’t remember what the title is—the book I wrote later. Uh, but based on my experience then, I, I knew later that I wanted to write a book that would provide people with the answers that I didn’t have at that age.

So, yeah, we, I was operating and my mom was operating in a world that, uh, did not provide the kinds of information and guidance that are available today to young people and to parents. And it was still a world where homosexuality was not discussed, uh, openly, and not nearly as visible as it is now. Remember it was 1977, and there were no gay celebrities, there were no gay sports stars, … There was, there, there… It was such a different world.

———

EM Narration: The difference between then and now came about in no small part because of the fallout from the Save Our Children campaign. So many people mobilized against that hateful campaign. Even I, in my own small way, was mobilized by Anita Bryant. I’m thinking back to Bebe Scarpi, last chapter, when she said—

Bebe Scarpi: If you get stepped on constantly, a little thing is enough to set people off like that. I can’t take this anymore.

EM Narration: Sometimes, enough is enough. Most gay people, then and today, just want to live their lives. But Anita Bryant and Save Our Children were coming after us. She had set people off. And in spite of a string of defeats, including Miami-Dade—or maybe because of those defeats—glimmers of hope started to appear.

———

Linda Tillery: [singing “Don’t Pray for Me”]

I know why you cry, Sister ’Nita

Life’s passin’ you by while rules enslave you

And it’s your blind innocence that traps you…

———

Unidentified Speaker: Supervisor Harvey Milk! [Cheering.]

———

EM Narration: In November of 1977, Harvey Milk became the first openly gay person elected to public office in California.

———

Harvey Milk: My name is Harvey Milk, and I’m here to recruit you.

———

EM Narration: After Milk took office as a member of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors, he almost immediately returned to campaign mode to fight the Briggs Initiative. Also known as Prop 6, Briggs had been spawned by the campaign to repeal Miami-Dade’s gay ordinance. Arkansas and Oklahoma had passed laws banning gay people from working in public schools and conservative California State Legislator John Briggs figured that sounded like a good idea for his state. But there was a growing backlash—to the backlash.

———

HM: I’m tired of listening to the Anita Bryants twist the language of the Bible to fit their own distorted outlook. Gay people all across this state, the Briggs can only be defeated if each and every one of you comes out to everyone you know. You must! [Cheering.]

———

EM Narration: Milk wasn’t the first openly gay person elected to political office in the U.S., as many people believe. That was Kathy Kozachenko, an out lesbian who was elected to the Ann Arbor City Council in Michigan in April of 1974. But Harvey was so high profile—and loud. Here he is confronting California State Senator John Briggs in September of 1978.

———

HM: You’re the one who keeps bringing up this phony recruitment. You know you’re lying. You know you’re changing the statements around. And you’re doing that all the way around, just like you, you shifted the money around in your campaigns. And you talk about morality. And I question, what is your real motive behind it? What is your real ambition behind this? What are you really using this for? And stop this phony issue that you know is a phony issue.

———

EM Narration: California’s former governor Ronald Reagan joined President Jimmy Carter, former president Gerald Ford, and Governor Jerry Brown in urging Californians to vote no on Prop 6. Reagan wrote in the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner days before the election, “Homosexuality is not a contagious disease like the measles. Prevailing scientific opinion is that an individual’s sexuality is determined at a very early age and that a child’s teachers do not really influence this.”

———

Linda Tillery: [singing “Don’t Pray for Me”]

You needn’t worry about my soul, ’Nita…

———

EM Narration: As we say in the neighborhood, “No shit, Sherlock.” The Briggs Initiative was rejected in November 1978.

———

Linda Tillery: [singing “Don’t Pray for Me”]

You need the time to heal your own

We’re coming out to walk in the sunlight

We’re coming out to fight for right…

———

HM: To the gay community all over this state, my message to you is, so far a lot of people joined us and rejected Proposition 6, and now we owe them something. We owe them to continue the education campaign that took place. We must destroy the myths once and for all, shatter them. We must continue to speak out. And most importantly, most importantly, every gay person must come out.

———

EM Narration: That same election day in November of ’78, Charlie Brydon was crossing his fingers in a ballroom in Seattle.

———

EM: What was election night like?

CB: Well.

EM: Did you…?

CB: We had the biggest hall in town, and, uh, all the television stations were there. And as it, as the early returns came in and showed there was going to be an overwhelming defeat, the people just jammed the place.

EM: Defeat of the repeal.

CB: Of the, of Initiative 13. So many people came downtown that, that night to the hall, the fire department showed up and they were going to shut us down because we had, we had overcapacity in the building. But it was very exciting. We had a telephone line down to California and the No on 6 Committee. And we, we were, relished the idea and the fact that we won up here by a greater percentage than the vote was in California.

———

EM Narration: The Seattle effort to repeal protections for gay people was beaten back by a popular vote of 63 percent to 37 percent.

———

Linda Tillery: [singing “Don’t Pray for Me”]

Don’t you pray for me, ’Nita…

———

EM Narration: Anita Bryant faced consequences for her actions: boycotts, canceled TV shows, and she was dropped by the Florida Citrus Commission. The 1970s ended for her with a messy divorce and later she would declare bankruptcy, twice.

But the Save Our Children campaign’s success was noted. Less than two years after the defeat of the Briggs Initiative in California, the firebrand televangelist Jerry Falwell had established the so-called Moral Majority. It was a coalition of conservative evangelicals hell-bent on influencing the national Republican Party. Until it was dissolved in 1989, the Moral Majority wreaked havoc throughout the country on a wide range of social and cultural issues, from promoting anti-gay laws, to legislating against abortion and pornography, and blocking ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment.

Like I said, with my mother things were complicated. We had a relationship where I was sometimes the adult, sometimes the child. She could be unpredictable. Sometimes she scared me, yet I desperately wanted her approval.

But after that night, after gliding down the driveway with the headlights out and creeping up the stairs trying to sneak in unnoticed, after seeing her bedroom door cracked and the light on, after hearing her call me in, after having one of the most consequential and terrifying conversations of my life, and after ending that conversation with her disappointment so heavy in the air it crushed my chest… After all that, my mother did something totally unexpected.

———

EM: She very quickly pivoted and made me feel completely comfortable and embraced. She, um, uh, I remember a conversation we had in the kitchen—again in the kitchen, next to the refrigerator—and she had been dating at that point and occasionally brought home a man. And I think at that point she might have had her much younger boyfriend. And she said, um, that she didn’t have a double standard. That if she could bring a man home, that I could as well. And she bought me a full-size bed; she replaced my twin bed with a full-size bed.

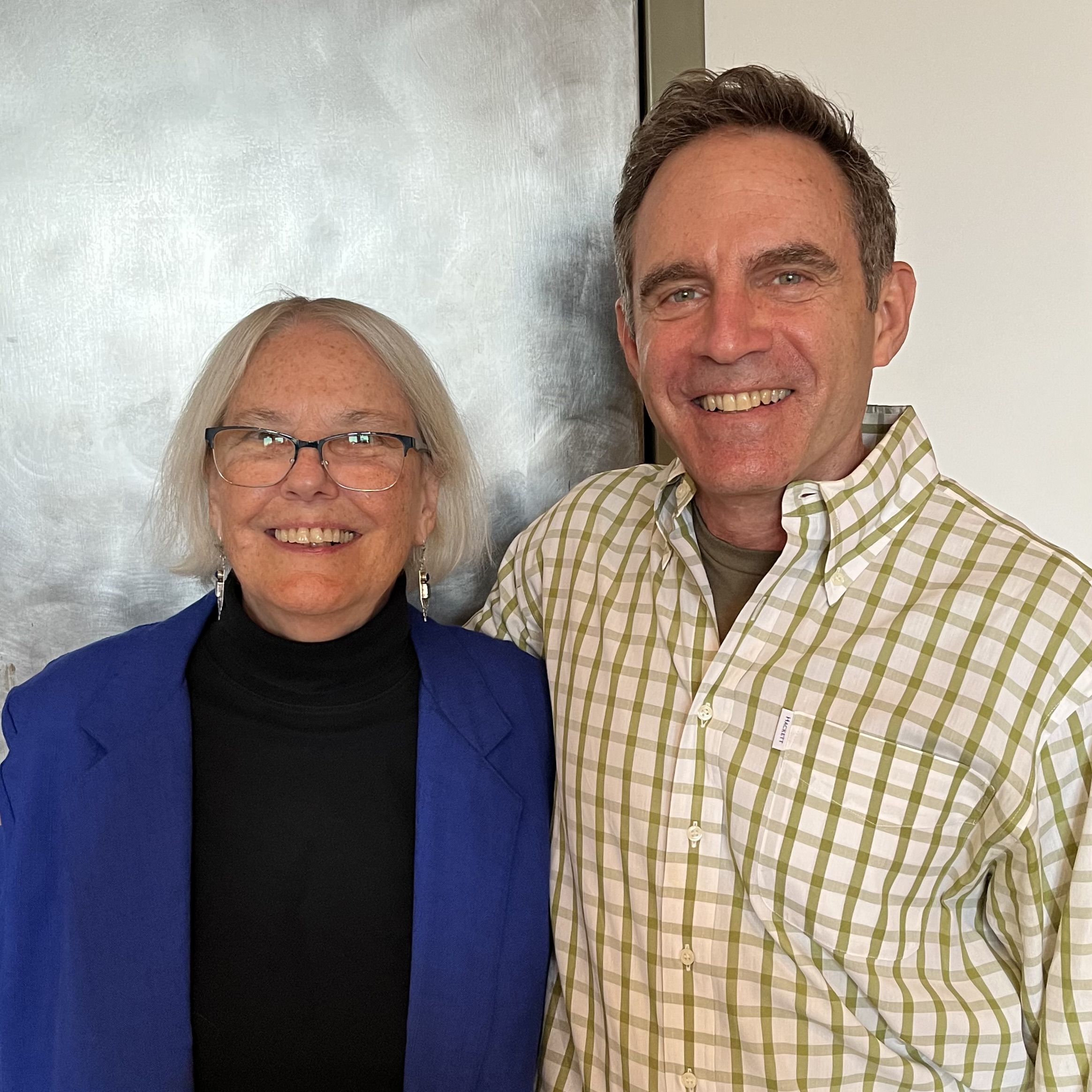

She was always very welcoming of boyfriends. So, um, really in some ways she was a marvel, as I look back, because—I remember one time I had a boyfriend in the kitchen. He was in a bathrobe. It was the first time I think she met a boyfriend who stayed overnight. She was perfectly welcoming. She made breakfast for us. So she was really terrific. But it was 13 years before she went to a PFLAG meeting. Um, and then she jumped in with both feet.

SO: So what did that look like? This would have been 1990 then, I guess?

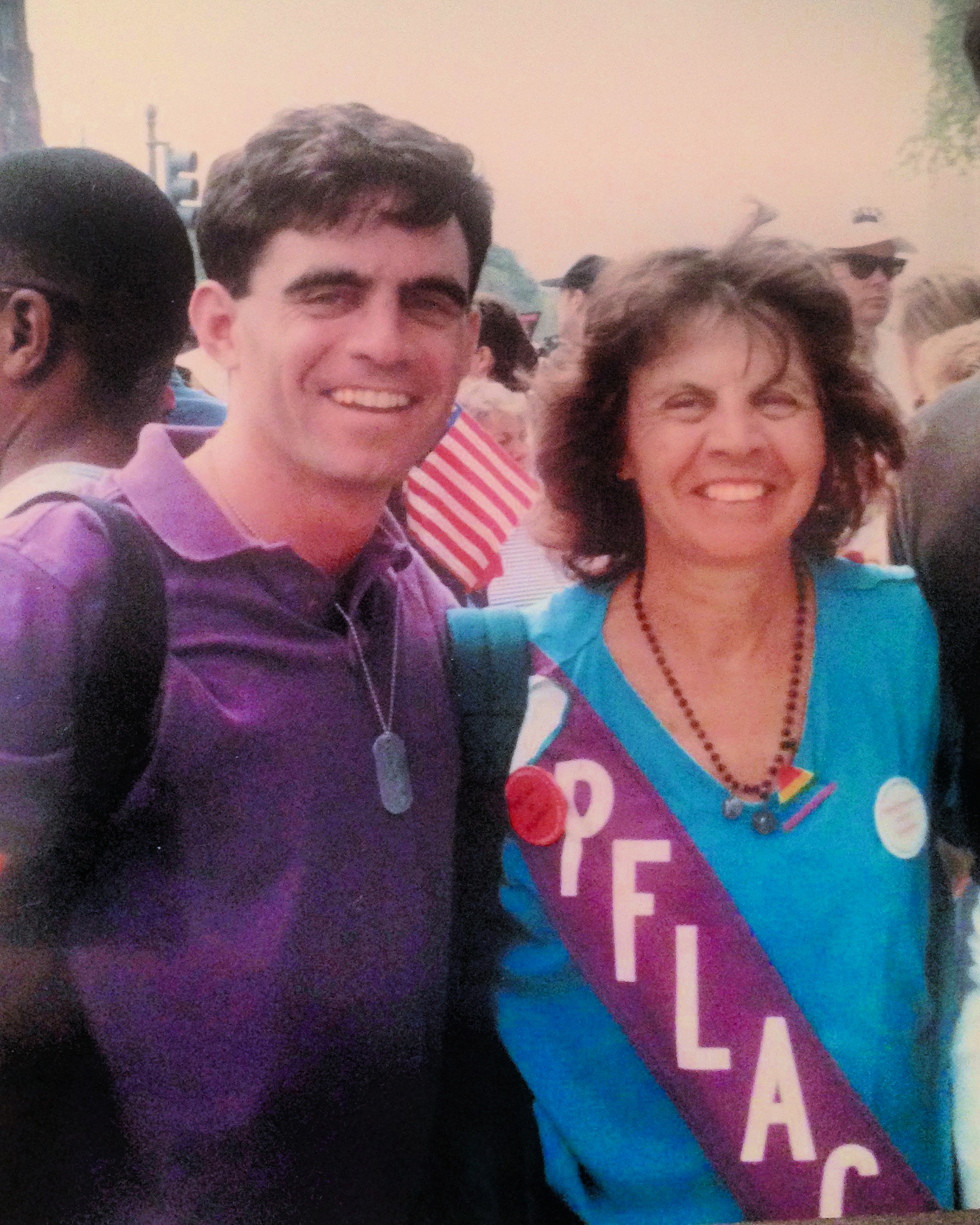

EM: It was the early ’90s, yes. Um, she started going to meetings and then she, uh, uh, I remember we went to the ’93 March… I went to the 1993 March on Washington, as did she. And she had her PFLAG sash and all of her buttons. And it’s one of my favorite photos with my mom, um, which we’ll, which we’ll include in the episode notes. And, um, she co-chaired a New York City PFLAG dinner, which was really wonderful.

Um, she joined me in an event at the Gay Center here in New York—now the LGBTQ Center, uh, when my book Making History—which is the, was the original name of the Making Gay history book—she joined me for an event, a launch event. We had maybe 300 people at the Center, and my mom and I read an excerpt from the book. My mom played the Jeanne Manford part; I played the Morty Manford part. Jeanne Manford was in the audience. It was one of the most moving experiences I had when that book was published. Uh, Morty had just died a few weeks before and Jeanne was in the audience. Um, and my mom and I were featured on the front page of the Metro section of what was then New York Newsday—doesn’t exist anymore.

SO: Wow.

EM: Um, and it was great. And I remember my, one of my relatives said to me—um, uh, had some concern about my mother sort of moving in on my territory.

SO: Hmm.

EM: Um, I was really happy for her to enjoy the spotlight over this. I know she got a lot of pleasure from, uh, being the mom of a minor gay celebrity. Uh, I remember her telling me that she was traveling once—and this was before Making History was published—and she was, uh, reading a copy of The Male Couple’s Guide to Living Together, my first book, and she got into a conversation—uh, it was in the Caribbean, I think—with somebody who was there. It was somebody who recognized the book and she very proudly said she was, she was the mother of the author.

So, I have such a complicated relationship with my mother, because in some ways I so resented her, but also I really was protective of her and wanted her to have a good life. She had had a hard life. Her father died when she was 12. Um, she was an only child. Her mother was an immigrant. They were poor. Um, my mother couldn’t go to college because she had to go to work to support, help support her mom. Um, and then she married my dad who was mentally ill. She didn’t know it at first. She was mentally ill, which was undiagnosed, too.

So, I was very protective of her, um, and was happy to see her happy. And if, if, if her being happy meant having her at the podium with me at the Center—and she was a good reader, by the way—I was really happy for it.

Um, something I didn’t know, and I only learned at a meeting with Danny Dromm, who was a city councilman here in New York—a former city councilman now—and a real hero of the movement. When I met with him, uh, five years ago the first time to talk about education issues in New York City, um, and how Making Gay History might have some involvement in, in developing curriculum materials, Danny mentioned that he knew my mother. My mother had been dead for years by this point. And I said, “How did you know my mother?” He said, “Well, she helped cofound PFLAG Queens, the Queens chapter of PFLAG, with him and with Jeanne Manford. I didn’t know.

SO: Wow.

EM: She never told me. And I don’t think I’m forgetting this; I think I would’ve remembered if she’d told me. And I think that she didn’t tell me—if that was indeed the case—I think she didn’t tell me because I had given her a little bit of a lecture about how this was my issue, not hers, and that she had become this activist—and I know this is a problem for PFLAG parents sometimes, um, that they wind up being more involved than their kids. But I, I think I harbored a little bit of a resentment that, that my mother had become this activist.

Um, but then I was also proud of her. She had gone back to college. She got her social work degree. She volunteered at the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and she ran a support group for gay men whose partners had died from AIDS. So she was, um, a good person, and she was protecting herself probably by not telling me that she had helped to cofound Queens PFLAG. And I wish, I wish she were around and I could say, “Ma, why didn’t you tell me?” I’m so, you know, I’m really proud of her. Um, but I never got to, uh…

Shane, you get me to cry every time. Um, she’s not around for me to tell her. She’s been, she died in n—in, uh, 2000 and, uh—what year?—2004. She was 73. Long time ago. And it was years later that I learned that she’d cofounded PFLAG Queens, so…

SO: Anything else you’d wanna tell her?

EM: Oh god. Shane, there are so many things I could tell my mother, um, but I think I will refrain right now. Um, I think I would tell her that, um, I was, I was harder on her than I needed to be. That she was really, um, in some ways had done the right thing, mostly the right things, in dealing with me. That I wish she hadn’t said she was disappointed, but, um, as far as the range of reactions that parents have to gay kids, it was pretty good.

———

EM Narration: Sometimes good things happen for the wrong reasons. In an ideal world—there’s of course no such thing—I would have done things differently. I wish I hadn’t said, “See you later, Ma,” that night she asked me if I was gay. I wish I’d gone to see a psychiatrist and she’d gone to PFLAG sooner.

I wish I’d known the extent of my mom’s allyship and activism, and I wish I’d been able to thank her for all her good work before she died nearly 20 years ago at the age of 73.

I wish it hadn’t taken a hateful figure like Anita Bryant and her homophobia to reinvigorate the fight for gay rights. And I wish it hadn’t taken all that hateful rhetoric to provoke a defiant streak in me.

But that’s how it happened. Anita Bryant’s grievances galvanized us. She was the perfect symbol for an appeal to so-called family values and she was also—by the way, there was no small amount of misogyny at work here, too—the perfect symbol to direct our anger toward. So, yeah: thank you, Anita.

———

This season of Making Gay History was produced and written by me, Eric Marcus, and Making Gay History’s founding editor, Sara Burningham, with archival research and production assistance from Brian Ferree and additional archival research from Tyler Albertario. Special thanks to interviewer-slash-oral historian Shane O’Neill. Our studio engineers for this episode were Casey Danielson and Charles de Montebello. “Coming of Age During the 1970s” was mixed and sound designed by Anne Pope.

This season of Making Gay History was recorded at CDM Sound Studios. Our theme music and additional scoring were composed by Fritz Myers. Our new theme features flautist Anna Urrey.

Many thanks to our hard-working crew at Making Gay History, including deputy director Inge De Taeye, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter.

Thank you as well to the New York Public Library Manuscripts and Archives division, UCLA Film and Television Archives, K-PIX TV in the Bay Area, and WTVJ Miami.

“Don’t Pray for Me” was performed by Linda Tillery, composed by Mary Watkins, and released on Olivia Records.

Making Gay History is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Calamus Foundation, and Christopher Street Financial. We’re deeply grateful to Patrick Hinds and Steve Tipton for their two-year grant in support of Making Gay History’s mission to bring LGBTQ history to life through the voices of the people who lived it. And thank you to Ted Smith and Matt Vieyra for their recent major gifts. I wrote to Matt to ask why he decided to support Making Gay History and he wrote, “I felt inspired to donate to MGH because across the nation I see states passing laws discriminating against LGBTQ+ people and I feel it’s critical, now more than ever, that we learn our history to know what worked and what didn’t work in the past to be successful in our fight for equality today.”

Please consider joining us on Making Gay History’s Patreon channel, where you can support our work and at the same time gain access to exclusive interviews, behind-the-scenes conversations, and additional archival audio excerpts that we think you’ll enjoy hearing. Sign up for just $5 a month at patreon.com/makinggayhistory or go to makinggayhistory.com and click on the Patreon button.

Right now, on our Patreon channel, you can hear my conversation with Ethan Geto, who was one of the young activists who traveled to Florida to help organize against Anita Bryant’s campaign to repeal the Miami-Dade ordinance. There’s a lot we can learn from the people who fought against a past generation’s anti-gay bigots.

———

Not quite ready to go yet, because my former sociology professor, Eileen Leonard, had a mother-son story of her own to tell me—a story about her and her son Tim and the ripples of history that she shared with me as we were wrapping up our conversation, our first conversation in more than 40 years.

———

EL: But you know what’s interesting, Eric, is that Anita Bryant helped you. You helped my son come out to me. Uh, and, um, when my husband and I both thought that when, when Tim was in high school, that, that, that he might be gay—you know, there weren’t a lot of the typical going out with girls and posters on the wall in the bedroom and all this awful stuff.

Uh, and I thought maybe I should ask him about it, and then I thought, no, maybe this is something that’s private and I should wait until he comes to us—that, that this wasn’t something as a mother I should be broaching with him. So I did what I usually do. I started doing research, and I found one of your books.

And since I knew you and trusted you, uh, I found in that book, um, whether the—as I remembered, it was like a question and answer book, you’d ask questions and then give answers. And one of them had, must have had something to do with should parents broach the subject with, uh, with, um, their children. And my recollection of it was that your answer was yes.

And so that’s what I did. I went out for a walk with Tim and our dog and, uh, and I asked him. And Vassar helped me with this; I asked him whether or not he was questioning his sexuality. And he said yes. And, um, I threw my arms around him and thanked him for telling me, and we went on from there.

EM: That makes me, makes me cry.

EL: So you were a help to my family.

EM: Well, you were a help to me in being my sociology teacher so I could write that paper in your class. It just all comes full circle. Um, when, when was that walk? What year, and how old was Timothy then?

EL: He was a junior in high school.

EM: So that would’ve been what year?

EL: Uh, what year would that have been—2000? No, he’d graduated from college in 2000—early 2000s.

EM: Uh-huh, uh-huh. So 20 years ago.

EL: Yeah.

EM: Yeah.

EL: My son is doing great. He lives in, in New York City. He’s a member of the New York City Gay Men’s Choir, uh, Chorus. Uh, and, uh, he’s out and proud, so he’s doing very, very well.

EM: Is It a Choice? was published first in the mid-’90s… Um, uuuhh, yeah, mid-’90s. Had a hard time getting it published.

EL: Is that right?

EM: Yeah.

EL: Oh, god, that seemed to me, you know, recalling it, so informative and helpful.

EM: My, the editor who I tried to sell it to said, “We already know all these answers. Why do we need this book?”

EL: Oh. Oh, wow.

———

EM Narration: As I said to Shane O’Neill earlier in the episode, when I came out to my mother, there was no guidebook for me for how to talk to her and no guidebook for her for how to deal with me. My question-and-answer book Is It a Choice? was published 20 years after that awkward and painful conversation in my mother’s bedroom. It was the kind of guidebook I wish I’d had, and I am so glad it helped Eileen and Timothy Leonard.

Here’s another ripple of history, spreading out through the generations… I had coincidentally met Timothy Leonard through my work, decades after his mother had found my book. Tim works for the National Parks Conservation Association, and he had a role in the complicated process of getting Stonewall declared a national monument by President Barack Obama back in 2016. We met in the runup to the Stonewall 50 celebrations. Tim is now the NPCA’s Northeast program manager and leads meetings with the many stakeholders involved in managing and celebrating the Stonewall National Monument—including, from time to time, me. We never know how far these ripples will travel.

“Coming of Age During the 1970s” is a production of Making Gay History.

Join us next time for the final installment of this series. Chapter six: “Marching On.”

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###