Coming of Age During the 1970s — Chapter Four: Respectable

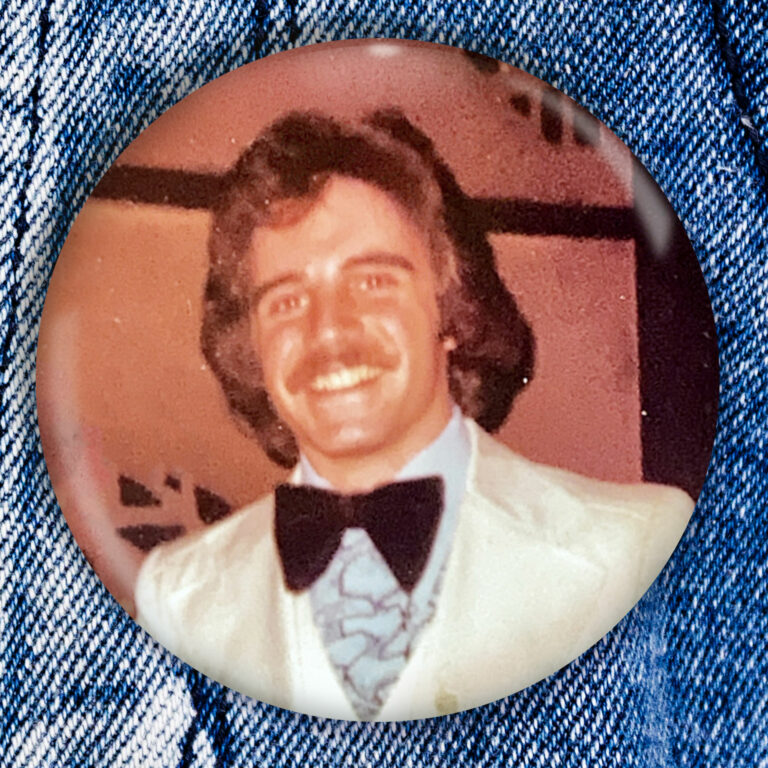

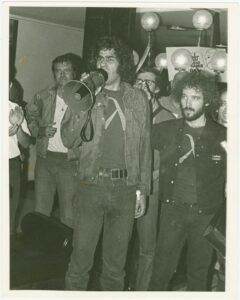

Eric Marcus in the mid-1970s at his cousin Jay’s wedding at the Chapel at the United Nations, New York City. Credit: Courtesy of Eric Marcus.

Eric Marcus in the mid-1970s at his cousin Jay’s wedding at the Chapel at the United Nations, New York City. Credit: Courtesy of Eric Marcus. Episode Notes

Gay rights activists in NYC are first out of the gate to propose anti-discrimination legislation, confident it will sail through the City Council. Instead, they hit a wall of ignorance and bigotry. Meanwhile, 15-year-old Eric happens upon some revelatory literature in his dentist’s waiting room.

Episode first published May 25, 2023.

———

Learn more about some of the topics and people discussed in the episode by exploring the links below. For contemporary press about the New York City Council hearings on Intro 475, have a look at the PDFs of the coverage in GAY embedded on this page.

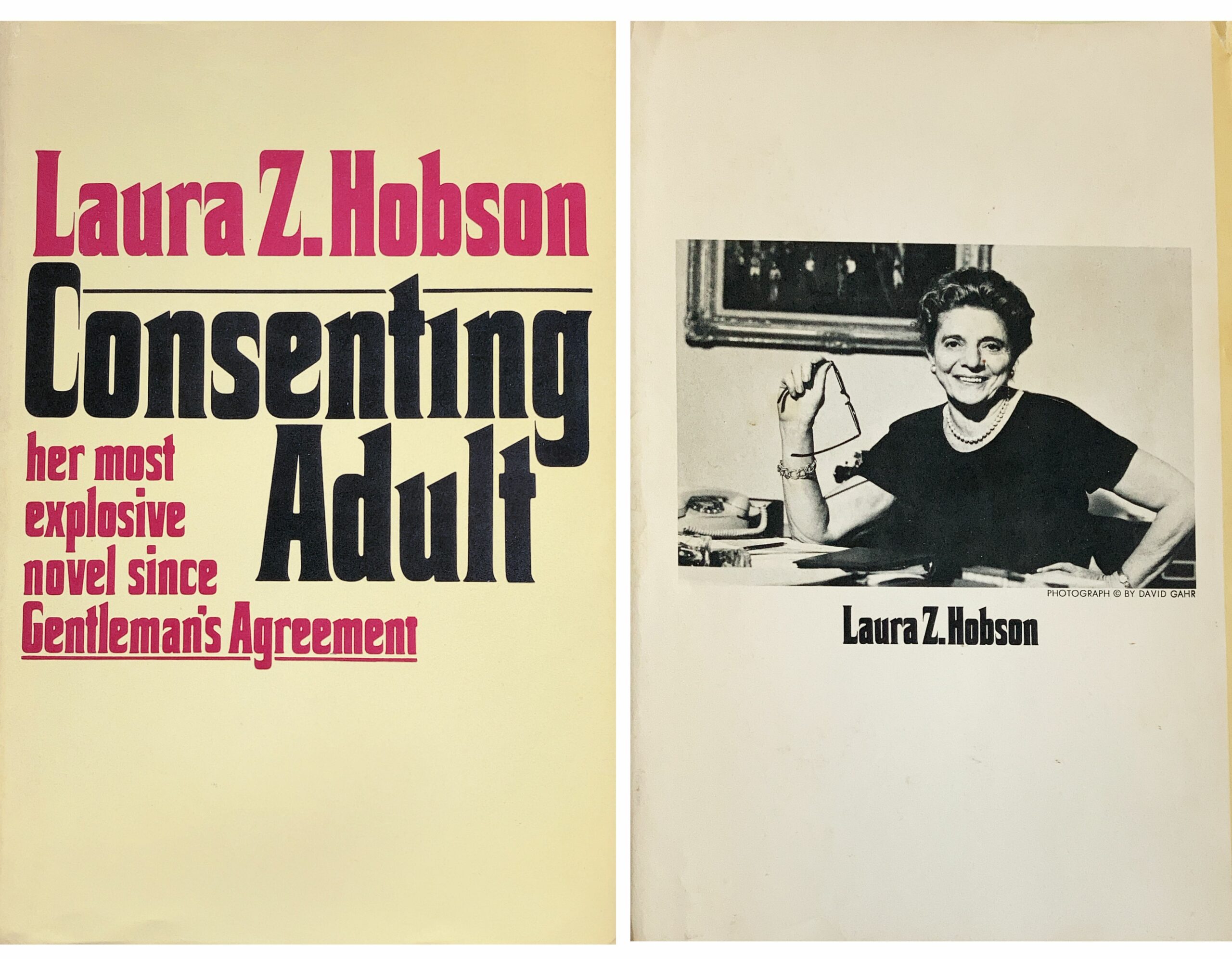

Consenting Adult by Laura Hobson:

- Contemporary press: 1975 New York Times profile of the author; book review in Vector, a gay magazine (page 17).

- Brief biography of Laura Hobson (Jewish Women’s Archive).

- Overview of Laura Hobson’s papers housed at Columbia University.

- 1985 TV movie adaptation starring Marlo Thomas: trailer; contemporary review in LGBTQ newspaper Our Own Community Press.

- 2017 audio interview with Christopher Hobson (OutCasting).

1970s efforts to pass a New York City gay civil rights bill:

- A short history (NYC Department of Records and Information Services).

- Contextualizing Intro 475 (OutHistory).

- Overview of GAA’s actions at City Hall , 1970-75 (NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project).

- Video presentation “ZAP!: The Push for a Gay Rights Bill, 1970-75” (Jay Shockley/NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project).

- “Homosexuals Bill Protecting Rights Is Killed by Council” (New York Times, January 28, 1972).

- Video footage of the April 27, 1973, GAA rally outside New York City Hall in support of Intro 475: WNYC-TV segment (starting at 2:43), including Sylvia Rivera leading a chant (NYC Municipal Archives); Betty Brown interview with Marsha P. Johnson (LoveTapesCollective/YouTube).

- “City Council Committee Rejects Homosexual Bill” (New York Times, April 28, 1973).

- “10 Gay Activists Are Seized in City Hall” (New York Times, May 1, 1973).

- News release from the Catholic Church opposing Intro 2 (Catholic News Service, May 8, 1974).

Bebe Scarpinato:

- Brief biography (Zagria/A Gender Variance Who’s Who).

- “Introducing New York’s Ms. Bebe,” 1973 profile and photo spread (Drag, Vol. 4, No. 13).

- “Bebe Goes to Hollywood … Almost,” 1977 essay by Scarpinato (Drag, Vol. 7, No. 25).

- Audio of Scarpinato discussing Sylvia Rivera and STAR (lbranson1/YouTube).

- Scarpinato’s Facebook page (incl. more recent photos).

Dr. George Weinberg:

- “Psychotherapist Who Coined ‘Homophobia’ Fought It All His Life,” obituary by Andy Humm (Gay City News, March 30, 2017).

- TV interview about conversion therapy (Gay USA, 2007).

The demonization of LGBTQ teachers:

- A short history (Karen Graves/History News Network).

- “How 2.8 million California voters nearly banned gay teachers from public schools,” recent column by Nicholas Goldberg about the 1978 Briggs Initiative (Los Angeles Times, August 4, 2021); primary sources about the Briggs Initiative (GLBT Historical Society).

- “Accusations of ‘Grooming’ Are the Latest Political Attack — with Homophobic Origins” by Melissa Block (NPR, May 11, 2022).

- “The Plight of Being a Gay Teacher” by Amanda Machado (The Atlantic, December 16, 2014).

Bathroom wars:

- A recent video explainer (PBS NewsHour, March 29, 2023).

- “The Sexist Origins of Gender-Segregated Bathrooms” by Jack D’Isidoro and T.J. Raphael (WNYC, The Takeaway, May 11, 2016).

- December 1971 New York Mattachine Times article admonishing those involved in the bathroom incident on the second day of New York City Council hearings related to Intro 475.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: We’re jumping around in the timeline again, heading back to a moment before Bob and my own special summer of love. Before Reverend Mullen. Before all that.

I’m Eric Marcus. This is “Coming of Age During the 1970s.” Chapter four: “Respectable.”

I’m at the dentist with a suspected cavity. Going to Dr. Teitelbaum, who is a German Jewish refugee, is always fraught, because getting a tooth drilled is excruciating. He doesn’t use anesthetic. It’s late 1974 and I’m about to turn 16. I didn’t even know that novocaine was an option. This would be my 14th filling.

While sitting by myself in the sunny waiting room, I try to distract myself by picking up a magazine from the stack on the side table. As I flip through its pages, my eye is drawn to a story called “Consenting Adult.” It’s an excerpt of a soon-to-be published novel. It’s about a mother and her journey to accepting her gay son. I’d never read anything about gay anything before, and I’m riveted. But not so riveted that I don’t look up between paragraphs to make sure that the receptionist, Mrs. Bloom, who is my classmate Jane’s mother, isn’t watching.

I read fast, knowing that I could be called at any time. The story’s narrator switches to the son, a very conflicted gay prep school senior, who finds himself at the counter of a diner with an attractive man—a stranger—in a black cable-knit sweater. As the scene unfolds and the young man is invited to go for a ride in the man’s new station wagon, my heart begins to race because I know instinctively what’s about to happen. The scene ends as I hope it will—and by then, I’m so excited that I’m praying I don’t get called until the embarrassing bulge in my pants recedes. I start imagining the death of my beloved cat, Tiger, which has always worked in the past.

I walk with my hands in my pockets into Dr. Teitelbaum’s office, picturing my dear Tiger in her death throes. But what I can’t push out of my mind is the preppy senior’s wish, following his back-of-station-wagon experience. He wishes he didn’t want so desperately something that would ruin his life. This same wish was becoming a mantra for me. In my heart of hearts, I know what I am. Seeing myself in that prep school senior whose life was a million miles from mine in every other way just reinforced that. Even if I’m terrified to name it and fully acknowledge it, my body knows exactly what I want. And almost as deep in my bones as knowing I’m gay is the terror that it’s going to ruin my life.

This was the water I was swimming in, as I settled into the dentist’s chair and gripped the seat’s padded arms in anticipation of the pain that I knew was to come…

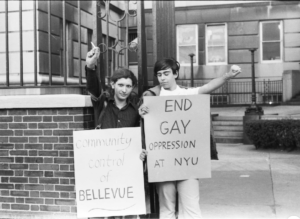

When the new activism of gay liberation exploded onto the political scene in the early 1970s, gay rights became imaginable—something worth fighting for. Not a dream of the hopelessly optimistic. New organizations like the Gay Activists Alliance, the Gay Liberation Front, Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, and Lesbian Feminist Liberation had started the decade demanding equal rights, and New York City was at the forefront. But in my hometown, a place we now think of as progressive, those demands for change were met with bigotry and, for want of a better word, stonewalling.

So this is a story about something that didn’t happen in the 1970s in New York. We didn’t get a gay rights bill. But it wasn’t for lack of trying.

———

Charles Pitts: This is Out of the Slough. I’m Charles Pitts.

———

EM Narration: The gay rights bill was first introduced before the New York City Council on January 6, 1971.

———

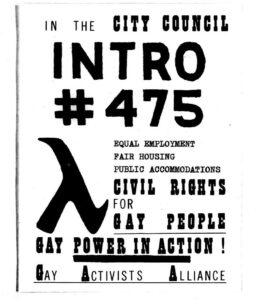

CP: You might ask, what bill is this? Well, it’s called Intro 475.

———

EM Narration: It was the first bill of its kind in the United States.

———

CP: Well, I have a copy here somewhere of the actual physical bill. I was gonna read it. I don’t know whether it would be very interesting. Sure, why not? We have lots of time. I’m gonna read this bill. Actually, I’m gonna excerpt it.

———

EM Narration: Basically, the bill would add sexual orientation to the existing non-discrimination ordinance.

———

CP: “The Council, the City of New York, Int. No. 475, January 6…”

———

EM Narration: It would outlaw discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in employment, housing, and public accommodations.

———

CP: What I’m really doing is reading a bill that’s already law, except that what they’re doing is adding “sexual orientation.” “Be it enacted by the Council as follows: Section 1. Section B1-2…”

———

EM Narration: I’m going to explain some process stuff here, with some very brief Making Gay History New York City civics. Before a bill goes to the full Council for a vote, it has to work its way through committee. The bill is assigned to a committee, the committee holds hearings, then the committee’s members vote on whether the bill should move on for a vote in the full City Council. In the case of the gay rights bill, every step was a battle.

Intro 475 was assigned to the General Welfare Committee. But all spring, nothing happened. Not a peep. In June of 1971, GAA, Daughters of Bilitis, Radicalesbians, and the Mattachine Society of New York held a candlelight march from the GAA Firehouse to City Hall to urge action, followed by a zap at City Hall the next day. Nine protestors were arrested trying to get into the building.

By September those protestors were acquitted, but there was still nothing happening with Intro 475, so GAA issued an ultimatum. In a letter to the City Council’s majority leader, and the chair of the General Welfare Committee, GAA said, “You’ve got until September 30 to hold a hearing.” This time, they got a response. The chair of the committee, Saul Sharison, told them, “I don’t take any shit.”

On September 30, GAA members zapped Sharison. They marched on his apartment building, and the activists lingered for days, handing out flyers. Six GAA members were arrested. Sharison announced that the general welfare committee would hold its first hearing on October 18.

———

CP: Hearings on that bill will be held Monday in the, uh, Council chambers at, um, City Hall or wherever Council chambers are. Well, that very neatly, uh, swallowed up about half an hour of airtime. This is easy. All I have to do is read, uh, bills.

I think it’s time for some music.

———

EM Narration: As the hearings finally got underway, the bill’s sponsors and many in the gay liberation movement hoped it might pass without too much trouble. It felt like the moment. But Intro 475 ran into fierce opposition almost immediately, fueled by a deep fear of losing the right to fire people because they were gay. Because what if they wound up being gay in a firehouse? Or in a police officer’s uniform? Or around the children—as a teacher in front of a classroom, god forbid.

———

Sylvia Spray: The rights of our children, the lives of our children, should come before gay liberation.

———

EM Narration: This is Sylvia Spray, a self-described housewife from Queens, testifying at that first hearing on October 18.

———

SS: The mothers are busy working. They’re busy fighting for women’s lib. But no one is fighting for the children! I’m talking for every parent. I assure you, you go all over the city. Ask any parent what they would want for their children…

Council Member Carter Burden: Well, there are about seven or eight parents sitting up here. And, uh, I’m a parent, and you’re not speaking for me, frankly.

SS: Well, you’re not, you’re not a mother. You’re a father.

Unidentified Council Member: Mrs. Spray, how do you know?

CB: Are you saying now that fathers are not supposed to be parents either?

SS: Oh, don’t gimme this equality stuff. A woman is not a man. A man is not a woman. A father is not a mother, a mother… I’m sick of this. It denies everything that we know instinctively is right in life and correct in life. All this talk—rhetoric, rhetoric, rhetoric, rhetoric, rhetoric—covering up the real facts.

I’m a middle-class housewife, but I’m a mother. They’re very prejudiced. They’re prejudiced against me as a middle-class housewife.

CB: What kind of homosexual would be harmful to the children?

SS: One that is not hiding it.

Hearings ICoverage of the first of the New York City Council hearings on Intro 475 on October 18, 1971, in the November 22, 1971, issue of GAY. Credit: HoustonLGBThistory.org.

———

EM Narration: Isn’t Mrs. Spray something? Like some kind of proto-Anita Bryant, just a little less… polished.

The second hearing, which took place on November 15, 1971, was an extraordinary and explosive day at City Hall.

———

Guy Charles: Everybody seems to have a tremendous amount of talking to up there and you get pretty damn mad when we interrupt you down here. We have some rights.

———

EM Narration: Gay activists were fighting back. This is Guy Charles, from GAA.

———

GC: I would just like to state we are not coming here for pity. We are coming here for our rights, which are guaranteed under the Constitution! And that is the Constitution of the United States that you are supposed to uphold, not as a bigot, not biased, but impartial.

———

George Weinberg: My name is Dr. George Weinberg. I’m a clinical psychologist and a writer. I’ve been working closely on various aspects of homosexuality and what it means in society for some years now, and watching different implications of our present system.

———

EM Narration: Dr. Weinberg spoke at the hearing as an expert witness. He argued that homophobia—a term he had coined a few years earlier—was the real problem and not homosexuals. That was apparently totally baffling to Council Member Michael DeMarco. He was a Democrat from the Bronx and led opposition to the bill.

———

Michael DeMarco: You stated before that a, a teacher who was teaching math, by his, by his teaching of math certainly cannot influence a child to become homosexual or have any tendencies. Am I correct?

GW: Well, they don’t. Let’s put it this way…

MD: Okay, they don’t…

GW: … there’s no motive to it. A teacher teaching math in high school wants his class to be quiet and learn math. He’s not cruising in class.

MD: Alright, let’s talk about a third-grade, fifth-grade child. A homosexual teaching, not through his teaching, but by his actions…

GW: What sort of actions? I don’t follow you. I don’t visualize it yet.

MD: Uh, feminine, feminine, uh, actions.

GW: Femininity.

MD: Right. Voice, motion, movement, … A teacher who is a homosexual—

GW: Right.

MD: Right? With the feminine actions, vo—uh, high-pitched voice, … Would, could, could this person have an influence on a third- or fifth-grade child?

GW: You mean make the, the third-grade child effeminate?

MD: Well, no—well, let’s say an influence on him.

GW: Well, you have to prove that it will have a, a deleterious effect. You’re punishing hundreds of thousands of people.

MD: Your testimony is that it will not have an effect?

GW: My testimony is it will not have any effect relating to whether the child becomes homosexual or not. Will it have an effect? Uh, uh, anything you see has an effect.

MD: So that a teacher behaving in a feminine, a masculine teacher behaving in a feminine way can have an effect.

GW: Listen, I just explained it to you. Anybody—a masculine teacher behaving in a masculine way could have an effect.

MD: Excuse me, Doctor. The radiators, we’re having trouble with the radiators. They keep hissing every so often.

———

EM Narration: What Councilman DeMarco sarcastically called the sound of “radiators” was actually the sound of protestors in the Council chamber reacting to the warped logic he was intent on pursuing. But the same themes kept coming up. It wasn’t the homosexuality that was the problem per se. It was the kind of homosexuals and how they might affect the children.

———

Council Member Theodore Silverman: My son is presently in class, let’s say, and he has a teacher, who’s Mister Schwartz. And one day Mister Schwartz comes into school as Miss Schwartz. What effect on his mind would such an act have, if any?

GW: Suppose you took, uh, a six-year-old child and said, “Billy, uh, that person wore a dress and was put into prison for two years for that.” The child would be appalled to discover that for wearing a certain kind of clothing, a human being was put into prison.

Council Member Carter Burden: If, uh, the Council, uh, sees this bill as meaning that, uh, overnight, uh, fifty thousand, uh, Mr. Schwartzes are gonna turn into Miss Schwartzes, uh, …

GW: Right.

CB: … you can forget about it. Uh, so I think one is a question of whether, to what extent, uh, that problem is even covered under legislation…

GW: I can’t conceive of it, right.

CB: … and what is the, what is the scope of the problem anyway?

GW: I’d say the, the, the scope of the problem is nil. Uh, homosexual men are men. Homosexual women are women. Uh, there’s no… [Applause.] And for those, uh, Mr. Schwartzes, uh, who—as they were referred to—who want to be Miss Schwartzes badly enough, they don’t go into the school system in the first place because, uh, of a lot of reasons. And, uh, there is no, uh, necessary correlation. Only a tiny, tiny, tiny fraction of homosexuals want to, uh, uh, be members of the opposite sex. They don’t think of themselves that way.

———

EM Narration: It was the oldest trick in the book: scapegoating. The demand for equal treatment at work, in housing, and in public accommodations was turned into a debate about child molestation and what just seeing trans people might do to young minds.

Here’s Sylvia Rivera, who cofounded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, sharing her memories of the hearings with me over a pot of chili she was cooking in her kitchen back in 1989.

———

Sylvia Rivera: The first year that we testified for gay rights—

EM: This must be ’71.

SR: Mm-hmm.

EM: There was some dispute about whether or not you’d testify, I would think.

SR: Well, we did testify. It was hard to get up there to testify because the Council kept on trying to push the drag queens in the background. Actually, B got up and gave her point of view.

———

EM Narration: The “B” Sylvia just mentioned is Bebe Scarpinato, or Bebe Scarpi. She was born in 1951, the same year as Sylvia, but while Sylvia was born in a hospital parking lot in the Bronx, Bebe was born in Queens, New York. And unlike Sylvia, who was homeless and hustling by the age of 11, Bebe went to Catholic school and studied sociology at Queens College. But Sylvia and Bebe were close friends, and they called each other half-sisters.

———

SR: Bebe—who you’ll never be able to interview—Bebe did so much for the movement in her… She was always on the background, but she was always, a co—you know, coordinating things.

EM: Mm-hmm.

SR: The first four years of the marches, she was always in the back.

———

EM Narration: It’s understandable if you haven’t heard of Bebe Scarpi before, but like Sylvia said, she was a Where’s Waldo of trans activism in the early ’70s. And Bebe often credited Sylvia with helping her find her identity as a trans woman. Or wait, let’s hear directly from Bebe how she identified at the time.

———

Bebe Scarpi: A homosexual who is a transvestite and who is undergoing a certain amount of transsexual changes with estrogen. It’s the closest I can get to a formal label that you can read in a book. I’d really rather be known as just Bebe, the person, and let the rest of the stuff go. But, however, when it comes to terms of identifying myself to a type—since people like to put things in types, and I do myself—that’s how I am as a person: homosexual, transvestite, transsexual.

———

EM Narration: Sylvia was right, I never did get an interview with Bebe. But that’s Ms. Scarpi speaking to Rudy Grillo in April 1972. Huge thanks to the LGBT Community Center Archive for access to this precious never-before-aired audio. So Bebe and Sylvia were both there to testify at the second hearing for Intro 475 in November of 1971.

You’re about to hear Sylvia and Bebe describe what went down in their own words, and you’ll hear tape from inside the Council chamber that hasn’t been aired in 50 years.

———

SR: I had something to say, you know, I gave my point of view. And then after that, you know, we went to the ladies’ room.

BS: Well, they were in female attire. And, you know, it caused a bit of confusion if they walked into the men’s room.

SR: We went to the ladies’ room. They wouldn’t let us in.

BS: The police stopped them, whereupon we decided…

SR: … we’ll just go into the men’s room.

BS: We would liberate the men’s bathroom and make it a transvestite bathroom, because after all, society oppresses us with the fact that we can’t pee, uh, at least publicly. When we walked into the men’s room, one of the councilmen…

SR: I forget the councilman’s name…

BS: It was a, a cute little, uh, paisan pig of mine named Councilman Michael DeMarco.

SR: He says, “And why should I have my children being taught by them, men that dress in women’s clothing?” Now here Bebe is going to become a teacher, okay? And we’re like, what is this man’s problem?

BS: So the transvestite half-sisters immediately reacted like, “Why don’t you call on one of us to talk?” And we caused a scene down there like they hadn’t seen and they’ll never see again because, like, we immediately got up and charged toward the front of the place. At which point I, uh, pushed the cop with me—you know, he came down the flight of stairs. It was really funny.

And, uh, when we got to the front, I realized that the situation would, would be lost unless one of us got to speak. It would just be a senseless demonstration. So while the others were screaming, I calmly raised my hand and I said, “Excuse me, please call on me.” In other words, I was giving a very false image of being sweet and content and kind, so they would call on me thinking I would not be one of them to say, “You’re a motherfucking pig,” which they were.

So they finally called on me. Of course I was very polite because I wasn’t gonna play their game and get emotional with them and forget what I was gonna say. I had a lot to say that day and I was gonna say it. They’re not the only ones who took high school debate. They thought, like, we got one of the freaks and this one we’re gonna run rings around. And I was playing like, “Of course I’m not insulted, I’ll answer any question you have, Mr. Sharison, Mr. DeMarco…”

Hearings IIReport on the November 15, 1971, New York City Council hearings on Intro 475 by Leo Skir in the December 20, 1971, issue of GAY. An account of Dr. George Weinberg and Bebe Scarpinato’s testimonies appears on page 2. Credit: HoustonLGBThistory.org.

———

EM Narration: On the day of the hearing, Bebe Scarpi was dressed in masculine clothes, and introduced herself as…

———

BS: I’m afraid I’m here as, uh, an individual, primarily. A person.

Unidentified Council Member: Would you mention your full name for the…

BS: Uh, Anthony Thomas Joseph Scarpi. I go to Queens College and I’m a member of GAA and the Gay Community at Queens, which is a group of homosexuals on campus. What I’m here doing—

Unidentified Council Member: Put, put the microphone up.

BS: I come out of a Catholic school background, you see, and everything. So I have the full [unintelligible] indoctrination. I can judge and tell where prejudice comes from, because I was indoctrinated with it. And I have overcome…

Unidentified Council Member: Mr. Scarpi, I thought you were gonna talk about the transvestite.

BS: I am. I’m getting to everything.

Unidentified Council Member: Okay.

BS: Don’t worry. Uh, in due time. There was a lot covered today.

Unidentified Council Member: Okay, okay.

BS: Mr. DeMarco seems fascinated by the fact that there are such things as transvestites, of which I am myself, although I’m not a female attire today. Anything he wants to know about him, we will gladly tell him in private and give him all the liberation he needs. [Laughter and cheering.] That’s right. The important thing—

Unidentified Council Member: Anthony, Anthony, why, why confine it to Mr. DeMarco? [Laughter.]

BS: Okay, we got room for all of you. But, uh, that’s not the point. You see, we are constantly being used to put down the whole issue of gay liberation. We are part of that. Sure, we have our own rights. As this particular bill was worded, to my knowledge, it does not include us. As it is worded, it states about our sexual preference, which is not the issue. That we choose to dress as females is an entire different thing when we choose to do it.

I’ve been sitting up here for two days being told how unnatural I am, how this I am, how that I am, and I’m having to prove my existence. And if you want an exact case of discrimination, just now when we’re trying to come down the stairs, we were almost forcibly detained by the police. I say almost ’cause we beat them to the staircase.

MD: Well, you say that because of our, a certain statement I had made, you and your girlfriends, I believe, got up and started…

BS: My sisters.

MD: … your sisters, I’m sorry—uh, your sisters got up and started running for the stairs…?

BS: If you get stepped on constantly, a little thing like you coming out and saying, “What if a teacher comes to a classroom in a dress?” uh, is enough to set people off like that. I can’t take this anymore. And youse people have the ability and the right to set things straight. You won’t give us no gold carpet, you will just give what is supposedly inalienable right.

I had a very good history teacher, he filled me with some kind of love for this country. And I see it turning its back on me. And then people wonder why a lot of people become revolutionaries when they try to work within… [Cheering.]

MD: But you made a statement before that, uh, these straight teachers had an influence on…

BS: They had no influence on my sexuality.

MD: Oh yeah, they had no influence—

BS: Absolutely not. We were all products of the so-called straight teachers. I don’t, I never had an admitted homosexual teacher. You always wonder about the influence. What influence could they have had? All of us here who are homosexuals have gone through a heterosexual education. I think it’s fortunate that we were able to turn out this way.

MD: Let’s, let’s talk about the bill itself. How do you feel now not being covered under this bill?

BS: As a transvestite?

MD: Yes.

BS: Well, I re—I recognize as an intelligent person two separate entities. See, cross-dressing, I personally feel… To fill you in on that, we are persecuted under a law which has to do with the Boston Tea Party about painting your face as an Indian, uh, to hide your identity for something, uh, you know, to do an illegal act.

If you come up to any of the places where the transvestites hang out, whenever policemen fill their quota, which they’re not supposed to have, which they do, uh, need arrests, they always can pick up three female impersonators—

SR: [Off mic:] Four.

BS: Four? And tell ’em, “You’re parading without a permit,” and there’s absolutely no recourse. So they could press criminal fraud against you and send you away for… What was it, a Class D felony, Sylvia?

SR: [Off mic:] Felony A.

BS: … a felony A for a considerable amount of the time just for going out in clothes. And with today’s unisex look, I personally feel these laws are unenforceable. But, as you can say, you can’t argue with a policeman who’s taking you off the street because then it’s resisting arrest. And if you win the other case, you lose that one.

MD: Okay. When you dress up in clothes of the opposite sex, who do you go out with at that point? Uh…

BS: Same people I go out in boys’ clothes, some of them are here. I’ve gone out with girls as a girl, too.

MD: No, I mean, you go out, you go out with men who dress… Here the point—I wanna make the distinction here so I understand it… You go out with other men who dress up like women also or other men who are just feminine?

BS: Everything.

MD: Homosexuals, homosexuals…

BS: I mean…

MD: It’s the radiators again. [Heckling from the audience.]

BS: No, uh, well, you know, like, you’re getting into an interesting area. I go out with whoever I feel like going out with. If I feel like going out with a woman as, myself being dressed as a woman, too, I do that. If I choose to go and have coffee or visit my sisters as a woman, I do that. I have been with them, as today, as a man, and I have been with women as a man. I have been with other homosexual men as a man and also as a transvestite. So transvestism to me is just an expression of my own personal being. My homosexuality is an expression of my ability to love. Transsexualism is just an expression of the manner in which I do it.

MD: Tony, if we follow through, if this bill was to pass, then the next bill would have to, would be, would have to protect your rights, am I correct?

BS: Yes, it would be really nice if, like, you were writing this bill—and I assume you are going to vote for it because there’s nothing wrong in it—you would actually… In your own consciousness, perhaps you would like to introduce the transvestite legislation…?

Unidentified Council Member: The transvestite is included in the term homosexual, isn’t it?

BS: No, it’s not.

Unidentified Council Member: It’s not?

BS: In fact, it took us years to get the homosexuals to include it.

Saul Sharison: Anthony, your testimony has been most helpful and we thank you for your appearance.

BS: Okay, thank you.

———

EM Narration: The inimitable Bebe Scarpi would go on to be a high school teacher, an entertainer, and continued her activism. She died in 2019.

———

Hearings IIICoverage of the December 17, 1971, New York City Council hearings on Intro 475 in the January 24, 1972, issue of GAY. Credit: HoustonLGBThistory.org.

———

The committee held another hearing in December of 1971. GAA kept the pressure on with leaflet campaigns and with zaps on the mayor, John Lindsay, who was showing only lukewarm support for the bill. In late January of 1972, the General Welfare Committee rejected Intro 475 for the first time. The New York Times reported Councilman Michael DeMarco—you know, the one Bebe was particularly fond of—as saying…

———

Michael DeMarco Voice-over: The homosexuals killed the bill themselves. Those who were undecided found their behavior generally repugnant in flaunting their gay liberation instead of stressing their civil rights.

———

EM Narration: It’s interesting isn’t it, how LGBTQ people are always accused of flaunting, when all they’re really doing is existing and being themselves?

The committee rejected the bill again in July of 1972. When April 1973 rolled around, it really seemed as though the gay rights bill was going to get out of committee and head to the Council for a vote. They needed a majority of eight votes from the 15-member committee, and advocates had heard there were 10 yes votes in the bag. As the committee met on April 27, around 75 members of the Gay Activists Alliance waited in the pouring rain outside City Hall to hear the results.

———

Marsha P. Johnson: Hey, hey, what do you say? Pass the bill or you’ll pay.

———

EM Narration: Betty Brown from the L.O.V.E. Collective was there, too—that’s Lesbians Organized for Video Experience. She was recording interviews with the protestors, including Marsha P. Johnson, cofounder of the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, plus an unnamed member of the Gay Activists Alliance.

———

Betty Brown: Why are you here today?

MPJ: Darling, I want my gay rights now. I think it’s about time the gay brothers and sisters got their rights, and especially the women.

BB: How, how will this affect your, your job?

MPJ: Darling, I don’t have a job. I’m on welfare. I have no intention of getting a job as long as this country discriminates against homosexuals. There’s only homosexuals, bisexuals, and trisexuals, darling. And there’s no straight people. Because it is trying out women, honey.

BB: Thank you very much for talking to us. Why are you here today?

Sue Schneider: I’m here ’cause I’m a dyke.

Protestor: Right on.

SS: Well, I, I mean, I hope they, you know, come to their senses and, and pass a normal bill. That’s, that’s why.

———

EM Narration: But somehow, those 10 yes votes had turned to eight overnight as members changed their minds. Then one member abstained. And another didn’t come back after her lunch break. The final tally was seven yes, four against, and one abstained. The bill failed, one vote short.

When the activists waiting outside in the rain heard the outcome, it was reported in the New York Times that they “gave out with a loud cry of dismay. About 20 then dashed to the nearby Brooklyn‐bound entrance of the Brooklyn Bridge and lay down in the soaking street to block traffic. The police quickly arrested them.” The Village Voice reported Marsha P. Johnson sang “Give Me That Lesbian Religion” and that Sylvia Rivera “lay flat on her back with her legs spread apart. She was dragged onto the curb, shouting ‘Gay Power, Gay Power!’ and then dragged away to the police van.”

There were more demonstrations late that night into the early morning in Greenwich Village at the site of the 1969 Stonewall uprising. A few days later, there were yet more protests. GAA targeted the city’s diamond jubilee with a zap during the celebratory ceremonies and Sylvia Rivera was arrested again.

———

SR: I climbed City Hall’s walls for the gay rights bill.

EM: What do you mean, you climbed City Hall’s walls?

SR: Oh, I climbed them. They wouldn’t let us in the front part of the building, and I told them, I said, let me show you how to get into a building. And then the cops were telling me, “Oh, well, Sylvia, jump.” I said, “What, are you fucking crazy?” I said, “I may be crazy to climb, but I ain’t jumping.”

EM: That’s all, and that’s what they would’ve liked best.

SR: Oh, yeah. They would’ve loved that.

———

EM Narration: In total, a dozen protestors were arrested. And Intro 475 was defeated again, a fourth time, in committee in December of 1973.

History of Intro 475Overview of the history of Intro 475 in the February 1974 issue of GAY. Credit: HoustonLGBThistory.org.

———

The scapegoating of “transvestites” was not just happening in the Council chamber. The Gay Activists Alliance was roiled by infighting over whose rights to fight for, and whether it was really the best time to include trans rights in the bill, whether they should be fought for somewhere else, some other time. The blame game over why the bill was rejected started up right after that dramatic hearing on November 15, 1971. The Gay Activists Alliance held a meeting a couple of days later. Lee Brewster, a founder of Queens Liberation Front, was there, and angry that so-called “straight homosexuals” were willing to drop transvestites from their lobbying to outlaw discrimination in the hiring of homosexuals by city agencies. Brewster’s remarks were reprinted in the GAA newsletter.

———

Lee Brewster Voice-over: Suddenly, just as victory is approaching for the gay movement, it is becoming increasingly apparent that the price may be at the expense and the exclusion of still yet another minority—the homosexual transvestite commonly known as the drag queen. You are the true faggots! You who have felt the sting of bigotry and discrimination may now try to sell your sister away and offer her up as a political sacrificial lamb.

———

EM Narration: By 1974, the pressure to exclude “transvestism” from the bill was intense. And so, a compromise. In April of that year, the General Welfare Committee voted on the gay rights bill for a fifth time. Intro 2, as it was now known, was finally voted out of committee, with an amendment. Here’s how Drag magazine reported it.

———

Drag Excerpt: The amendment stated that nothing in the definition of sexual orientation “shall be construed to bear upon the standards of attire or dress code.” The amendment was key to committee passage and the wording had been worked out carefully by Theodore S. Weiss and Carter Burden.

Bebe Scarpi, the director of Queens Liberation Front, met at City Hall with the sponsors and QLF’s attorney, Richard Levidow, a week prior to the voting on the bill. Ms. Scarpi and attorney Levidow submitted to the above wording as an alternative to getting the bill passed. The clause, according to Mr. Levidow, is unconstitutional and won’t hold up in court because of the equal rights protection of the U.S. Constitution.

“QLF gave in on being included in this piece of legislation because politicians were using the transvestite as a scapegoat for not passing the bill,” says Lee Brewster, former director and founder of QLF.

———

EM Narration: The compromise did not deflate the bill’s opposition. Here’s Peter Fisher, a member of the Gay Activists Alliance, speaking in the spring of 1974.

———

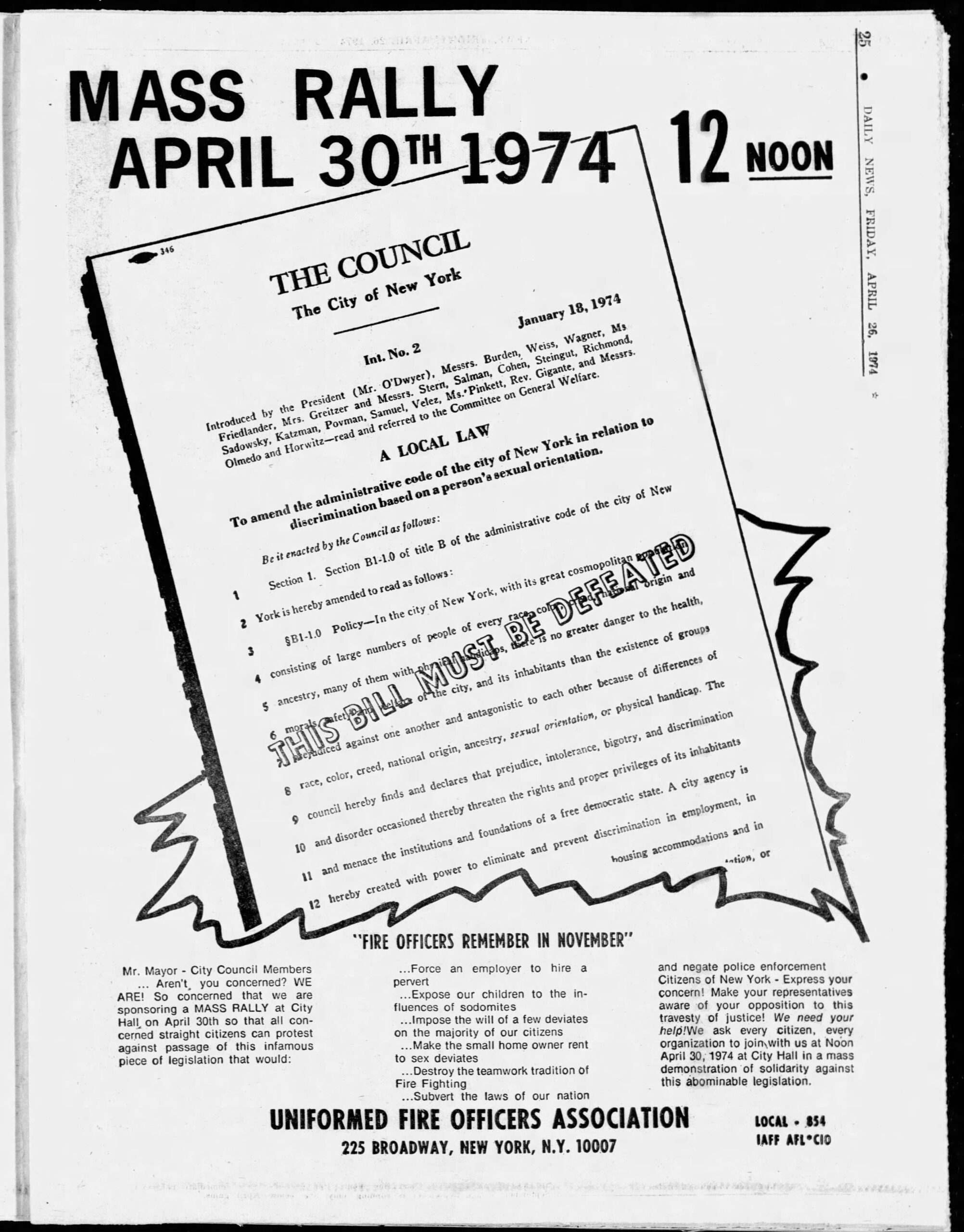

Peter Fisher: And the bill was voted seven to one out of the General Welfare Committee, now to come before the full City Council. And, uh, the stories in the press the next day all said that, uh, in political circles it was assumed that the bill would pass with no difficulty. But, uh, a few days later, a full-page ad appeared in the Daily News, uh, calling for a mass rally called by the, uh, Uniformed, uh, Firefighters Officers Association, interestingly enough, which is headed by one of the men who was accused of beating gays at the, uh, Inner Circle event last year. Anyhow, uh, the union took its funds and placed these ads in the Daily News and in the Long Island Press, where many firemen live. And, uh, they had a lot of sort of ugly language in their advertisement. “The bill would force employers to hire perverts, expose our children to the influence of sodomites,” et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. All the typical hate rhetoric.

———

EM Narration: In April of 1974, as the firefighters’ union demonstrated against Intro 2, the Catholic Church also went all-in against the bill.

———

PF: We always encounter a little bit of this. We were just surprised to find it so well-organized. The, uh, Catholic Archdiocese of New York put an editorial on the front page of the Catholic News, urging defeat of the bill, and sent letters out urging their people to write letters and defeat the bill. And as a result, we’ve, uh, apparently there’s been an outpouring of hate mail into the City Council.

———

EM Narration: The fight for a gay rights bill had been relentless for four years. As Intro 2 headed to the Council for a full vote, and the Church and the firefighters ramped up their campaign of hate and bigotry, Pete Fisher admitted that the odds were not looking good for the bill, and folks were starting to feel burned out.

———

PF: I know most of us who have worked closely on the bill feel we’ve been through this so many times, and really been, been hurt by it so many times with defeat after defeat. And to time after time have people vote that you’re not a human being, that you’re not entitled to the, the basic human rights that everybody else is entitled to—it’s a very, very painful thing to, to have happened after you’ve put in months and years of work and devotion towards the bill.

I don’t see the movement turning into violence, but I do see gay people becoming much more alienated from straight society. It’s very hard to feel friendly to a society that keeps dumping on you.

———

EM Narration: Intro 2 failed. The full City Council rejected the bill on May 23, 1974. Betrayed again when two of the bill’s original sponsors defected at the last minute. In October of that same year, a fire tore through the headquarters of the Gay Activists Alliance at the Firehouse. The interior was destroyed and GAA was evicted.

Are you tired? I’m getting tired. But, you see, every narrative arc about gay rights doesn’t end in a pot of gold. Sometimes you put in all the work, and still do not prevail.

Here comes Intro 554. Another bill. I’m not kidding. The New York Times reported that “all references to ‘transvestitism’ were excised” for this one. The hearings for Intro 554 took place in the General Welfare Committee. Yes, back in that committee again, in September of 1975.

———

Council Member Aileen Ryan: There is a three-minute limit on all speakers so that we may hear from as many persons as possible. I must advise you, we have over one hundred requests to be heard.

———

EM Narration: More hearings, more speakers. More of the same bigotry. Here’s Lawrence Washburn from the Guild of Catholic Lawyers.

———

Lawrence Washburn: You cannot force acceptance of homosexuality—which has not been accepted by society since the beginning of time—by a coercive, by a coercive statute, which forces people to associate with people whose conduct they disapprove and who forces them to let their children associate with them. Thank you, ma’am.

———

EM Narration: Here Council Member Thomas Manton is asking the New York City human rights commissioner, Eleanor Holmes Norton, whether anyone had really been discriminated against in housing because they were gay.

———

Thomas Manton: I really haven’t heard too many people come forward and say, “I made applications for an apartment in Queens or in the Bronx or… and I was denied.” Now maybe there are a lot of cases out there, but we really haven’t heard it. And I think the other members who have been on the committee as long as I have would, would back up that viewpoint.

Eleanor Holmes Norton: You might want to take into account what amounts to a national groundswell for such legislation, and the fact that there have been five years of struggle in this city for this legislation. I don’t think that would’ve occurred if nobody was being discriminated against.

———

EM Narration: The logic was like a Möbius strip. On the one hand, this is immoral and an outrage. On the other, it’s fine as long as you continue to hide it. But also, maybe no one’s discriminating because all the gays are hiding it. If you knew you could lose your job or your apartment if anyone found out you were gay, would you reveal it? And that twisted circular logic didn’t seem to have moved since the bill was first introduced. If anything, the bill’s opponents had become better organized and more entrenched.

———

Ronald Gold: Hello, I’m Ronald Gold, and this is a special Gay Alternatives show about the meaning, if any, of Intro 554, the gay civil rights bill, which was defeated in the General Welfare Committee of the New York City Council early on the morning of September 12, after nearly 14 hours of hearings. Which has now been defeated six times in the City Council, five times in committee, and once last year in the Council as a whole.

It was first introduced into the Council in January of 1971, and first came up for a vote one year later. It was the first such bill in the country. But it should be noted that, since then, 25 cities have passed legislation modeled after the New York bill. Nonetheless, this year, the gay rights bill suffered its most crushing defeat, losing by a vote of seven to four, the same count as on its first defeat back in 1972.

———

EM Narration: The coalitions and exuberance of the early part of the decade was transitioning. Virtually everyone involved in the effort to pass this bill was a volunteer. Think about the hours, days, weeks, months, and years of unpaid labor for the cause. Very few people live a life of uninterrupted radicalism. Most have chapters, at most. And it’s tiring, fighting all the time.

You can hear that in the round table of activists Ronald Gold pulled together for his show, Gay Alternatives, on WBAI, aired soon after the defeat of 554.

———

RG: Kitty Cotter, media coordinator for Lesbian Feminist Liberation; Frances Dougherty, board chairperson of the National Gay Task Force; and Arnie Kantrowitz, author and former Gay Activists Alliance vice president.

Kitty Cotter: I’m really sick of begging, handing out leaflets, you know? “Please sign my petition so, because I’m really a nice person. Don’t you see that I can smile, too?” It, it, you know, it’s almost as bad as when I first came out and started questioning whether gay was good or not.

Frances Dougherty: And then people said, “Ah, let’s get smart, you know. Let’s use the ‘in’ methods and let’s get to know the politicians and sort of deal with them on their terms.” And, uh, that doesn’t seem to have worked any better.

KC: People are cued into the, uh, to what the opposite, opposition has been saying: that if you pass such a law, you are saying that gay is just as good as straight, and that we won’t stop there. I certainly don’t wanna stop there. Then the next thing I’ll want is, uh, protective legislation for lesbian mothers and so on and so forth, so, um, you know, my feeling is…

RG: You might want to marry one of their daughters.

KC: Right, um, and I, I do feel a little strange not being able to say that.

RG: We’re a threat to the whole social structure. What we’re saying to people is, “Look, you know, you can recognize the homosexual part of yourself. We’re here to show you that you can.” Now, that just drives them up the walls. It puts them into a, a frenzy. So then on the other hand, we’re saying to them, “You don’t have to be threatened by us, we’re just like you,” which is a lie, you know?

FD: Yeah, we’re into the classic revolution versus reform—trying to hang onto your own gut reactions, trying to keep from alienating the forces that you need that are out there.

KC: We go through the ritual of the, of the legislative process until finally people get voted in or out or something, an earthquake changes the situation, but, um, so I’m not against having the bill come up again and again and again. But in terms of the energy, I think we have to—I have to set something of a little different priority.

RG: This kind of a bill is just simply something that I can’t put all my energies into in the future because I have more important things to do with my own life in terms of developing myself as a gay person.

FD: I think I am gonna try and strike more of a balance between going to meetings and playing the flute than I had last year when I ended up really exhausted.

Arnie Kantrowitz: I’m not too excited about, uh, going to lots of meetings anymore, um, but I am still passionately involved in the, you know, the ideals and the goals of the movement.

RG: There was some idea, I know, in part of our minds that the defeats of the bill were going to outrage all of our gay citizenry. They were going to get everybody together and say, look, you see how awful, uh, uh, we were treated and, and, uh, so we’re going to rise up en masse. Now that doesn’t seem a likelihood either, does it?

AK: Well, it’s more like, how awful we’ve been treated, let’s have another beer.

———

EM Narration: By the end of the 1970s in New York, still no bill had been passed. I could be denied housing, could be fired because I was gay. And not only was there no gay rights bill, New York’s sodomy laws were not repealed until the 1980s. We were not only denied protection from discrimination, we were illegal.

By the time I left for college, I had absorbed the message that if I was going to get by, I’d have to conform, act straight. It seemed to me the only way to avoid the fact of my sexuality ruining my life was to turn up the dial on my “Best Little Boy in the World” act. The City Council hearings and every message society sent made it clear that being an obvious homosexual would be punished. The Waspy, preppy senior in Laura Z. Hobson’s Consenting Adult was eventually accepted and embraced by his mother. So I practiced crossing my legs like a man, worked hard on my voice, ditching my Sylvia Spray-esque Queens accent, and sitting on my hands to make certain that no effeminate gestures crept out in conversation. It was a self-imposed straightjacket. One that I still haven’t fully escaped.

New York City wouldn’t pass a gay rights bill until 1986, becoming the 51st city in the U.S. to provide equal rights to gay people. It would be another 17 years before New York State passed similar legislation.

———

This season of Making Gay History was produced and written by me, Eric Marcus, and Making Gay History’s founding editor, Sara Burningham, with archival research and production assistance from Brian Ferree and additional archival research from Tyler Albertario. Our studio engineers for this episode were Cathleen Conte and Casey Danielson. Coming of Age During the 1970s was mixed and sound designed by Anne Pope.

This season of Making Gay History was recorded at CDM Sound Studios. Our theme music and additional scoring were composed by Fritz Myers. Our new theme features flautist Anna Urrey.

Many thanks to our hard-working crew at Making Gay History, including deputy director Inge De Taeye, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter.

Thanks to Jordan Reeves who was the voice of Lee Brewster. Tyler Albertario was the voice of Councilman Michael DeMarco in that one quote. And Jeffrey Masters voiced the articles from the GAA newsletter and Drag magazine.

Thank you as well to the L.O.V.E. Collective, the WBAI Pacifica Archive, the LGBT Community Center Archive Charles Pitts, Rudy Grillo, and Ronald Gold collections. Thanks also to the Vietnam Center & Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive, and the Rochester, New York Voices of LGBT History Project, at the University of Rochester.

Making Gay History is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, Christopher Street Financial, and recent major gifts from Andra and Irwin Press and Hal Brody and Don Smith. We’re beyond grateful to Patrick Hinds and Steve Tipton for their two-year grant in support of Making Gay History’s mission to bring LGBTQ history to life through the voices of the people who lived it.

Please consider joining us on Making Gay History’s Patreon channel where you can support our work and at the same time gain access to exclusive interviews, behind-the-scenes conversations, and additional archival audio excerpts that we think you’ll enjoy hearing. Sign up for just $5 a month at patreon.com/makinggayhistory or just go to makinggayhistory.com and click on the Patreon button. Next up on our Patreon channel is my conversation with trans scholar and activist Grace Lavery, followed by my conversation with Richard Socarides, the son of prominent anti-gay psychiatrist Charles Socarides, on coming out to his father.

———

By now you’ve probably noticed that sometimes when there are delicious details that don’t quite fit in, you’ll find me, lingering here, with a postscript.

There was another thing that always stayed with me after reading the excerpted mother-gay-son-coming-of-age-and-acceptance story in Dr. Teitelbaum’s waiting room, and it was the way the main character—remember the preppy, Waspy private school senior?—the way his mother comes to terms with his homosexuality. It offered this possibility I’d never dared imagine before, the possibility that my mother might accept me if I ever came out.

That passage I read made my future a bit more real and a bit less terrifying. It meant a lot and I held it close. But there was so much more to the story of Jeff, the tall, blond, baseball-playing senior, than I could possibly have imagined sitting there in Dr. Teitelbaum’s waiting room—a story I only discovered decades later. You see, Laura Z. Hobson’s book was based on a true story. Her own son’s story. In fact, she used a private letter he wrote her on the first page of the book. Without his consent. Ironic, no?

———

EM: Why did you decide to come out?

Christopher Hobson: It was such a fucking relief, you know, not to have to bottle this stuff up inside yourself, uh, to turn the tables. Uh, as soon as you say, “This is what I am,” then, uh, the problem transfers from you over to the other person, if it transfers at all, if the other person has a problem.

EM: When did you first learn that your mother was going to be writing a novel concerning homosexuality?

CH: Um, I moved to Detroit and from there I sent my mother a letter saying, roughly, that I was now involved in the gay movement and so on and so forth.

EM: So you wrote to your mother to tell her about the movement?

CH: That’s right. And immediately the reply came back, “Now I can write this novel that I’ve been thinking about for many years.” So…

EM: And what did you think when she said that?

CH: I thought that she was appropriating my life and using it for her novel.

EM: And did you tell her that?

CH: Yes. So we went into a period of very deep conflict that lasted for a very long time. Uh…

EM: Years?

CH: Years.

EM: How many years?

CH: Um, as many years as it took to write and publish the novel, and…

EM: It was published in…

EM & CH: 1975.

CH: So this is, that’s five years. And, uh, she reproduces the letter that I sent to her—not the exact text, but in substance, the, that letter—uh, on the first page of Consenting Adult, which is one of many reasons that, uh, my reaction to the novel, initially and for many years, was extremely hostile.

There were a lot of things that she changed and a lot of things that she didn’t. Uh, one thing was she made, uh, uh, Jeff tall and blond and a baseball player. And another thing is that she made him most definitely not an intellectual. Uh, it was difficult to deal with some of that.

EM: What did you, what did you say in the letter? If you can just paraphrase.

CH: No, I don’t want to.

EM: Okay, then never m—

CH: You, you can read it in the book.

EM: I’ll read it in the book.

———

EM Narration: And that letter was just the tip of the iceberg. Complicated. It was also complicated with my own mother.

More on that next time, in Chapter 5, which we’re calling, “Thank you, Anita.”

“Coming of Age During the 1970s” is a production of Making Gay History.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###