Rev. Carolyn Mobley-Bowie

Rev. Carolyn Mobley-Bowie, then vice-chair of the Atlanta Gay Center, leading a group of demonstrators in a rendition of "United We Stand, Divided We Fall," in protest against the First Baptist Church's Rev. Charles Stanley's homophobic remarks about AIDS, Atlanta, Georgia, February 9, 1986. Credit: Courtesy of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Rev. Carolyn Mobley-Bowie, then vice-chair of the Atlanta Gay Center, leading a group of demonstrators in a rendition of "United We Stand, Divided We Fall," in protest against the First Baptist Church's Rev. Charles Stanley's homophobic remarks about AIDS, Atlanta, Georgia, February 9, 1986. Credit: Courtesy of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.Episode Notes

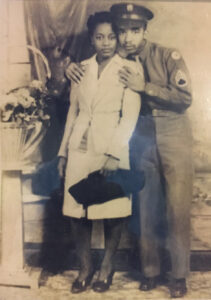

Growing up in the segregated South, Rev. Carolyn Mobley-Bowie knew the challenge of finding an accepting place in the world—a challenge that only grew when her attraction to women came into conflict with her devotion to God. The predominantly gay Metropolitan Community Church offered refuge.

———

Learn more about Rev. Carolyn Mobley-Bowie in this short profile and this oral history. Rev. Mobley-Bowie has been involved with the LGBTQ-affirming Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) for 50 years—first as a friend of the church and lay volunteer, later as an ordained minister, and currently as a member of the church’s elder council. Many of her sermons, like “Love Is Calling,” are available on YouTube.

MCC was founded in late 1968 by Rev. Troy Perry. He started out in his Los Angeles living room with just 12 congregants. To reach potential new members, Rev. Perry placed ads in the Los Angeles Advocate (later renamed The Advocate) and other gay publications. His church grew quickly and attracted attention from the mainstream press. Early media coverage included this 1969 Los Angeles Times article and this TIME magazine profile from 1970. To learn more about Rev. Perry and MCC, check out this timeline, watch this documentary, or read this profile from the ONE Archives.

After graduating from the Interdenominational Theological Center in Atlanta, Rev. Mobley-Bowie worked for the Southern Baptist Convention, a denomination known for its homophobic views; during the time Rev. Mobley-Bowie was employed by the Southern Baptists, they openly embraced anti-gay crusader Anita Bryant. It was not a welcoming environment, and in 1981, five years into her employment, Rev. Mobley-Bowie was asked to resign on suspicion of being a lesbian.

Throughout the rest of the 1980s, Rev. Mobley-Bowie held various jobs in the secular world, which gave her the freedom to become a more visible presence in the gay rights movement. She flourished in Atlanta, a center of Black gay activism. She became a board member of the Atlanta Gay Center, and was an early AIDS educator and advocate, joining organizations like AID Atlanta, the city’s main AIDS service agency. Learn more about the history of the AIDS crisis and AIDS activism in Atlanta’s Black gay community here. For a deep dive into lesbian and gay activism in Atlanta from the late 1960s to the mid-1990s, try this dissertation; for a bite-sized history, go here.

In the mid-1980s, Rev. Mobley-Bowie became a founding member of the African American Lesbian Gay Alliance (AALGA), an organization formed to bring Black gay and lesbian people together to help them address the unique challenges they faced. One of the goals—as defined by AALGA’s founding co-chair, Marquis Walker—was “to become as proud of our gayness as we are of our Blackness.” Walker died just a few months after AALGA came into existence; you can watch a brief clip of him at 50:40 in this video.

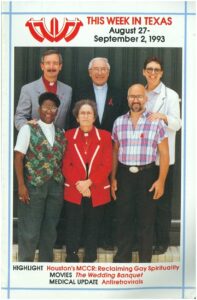

In 1990, Rev. Mobley-Bowie left Atlanta to join Resurrection MCC in Houston, Texas, as assistant pastor. During her 15 years at the church, she also held the positions of director of Christian education and associate pastor for congregational care, outreach, and community partnerships. Explore some of Resurrection MCC’s history here, and read the memories of an early member here.

Recognizing how closely Black ministry and Black political action have historically been entwined, in the episode Rev. Mobley-Bowie considers her work within the tradition of activist ministers like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

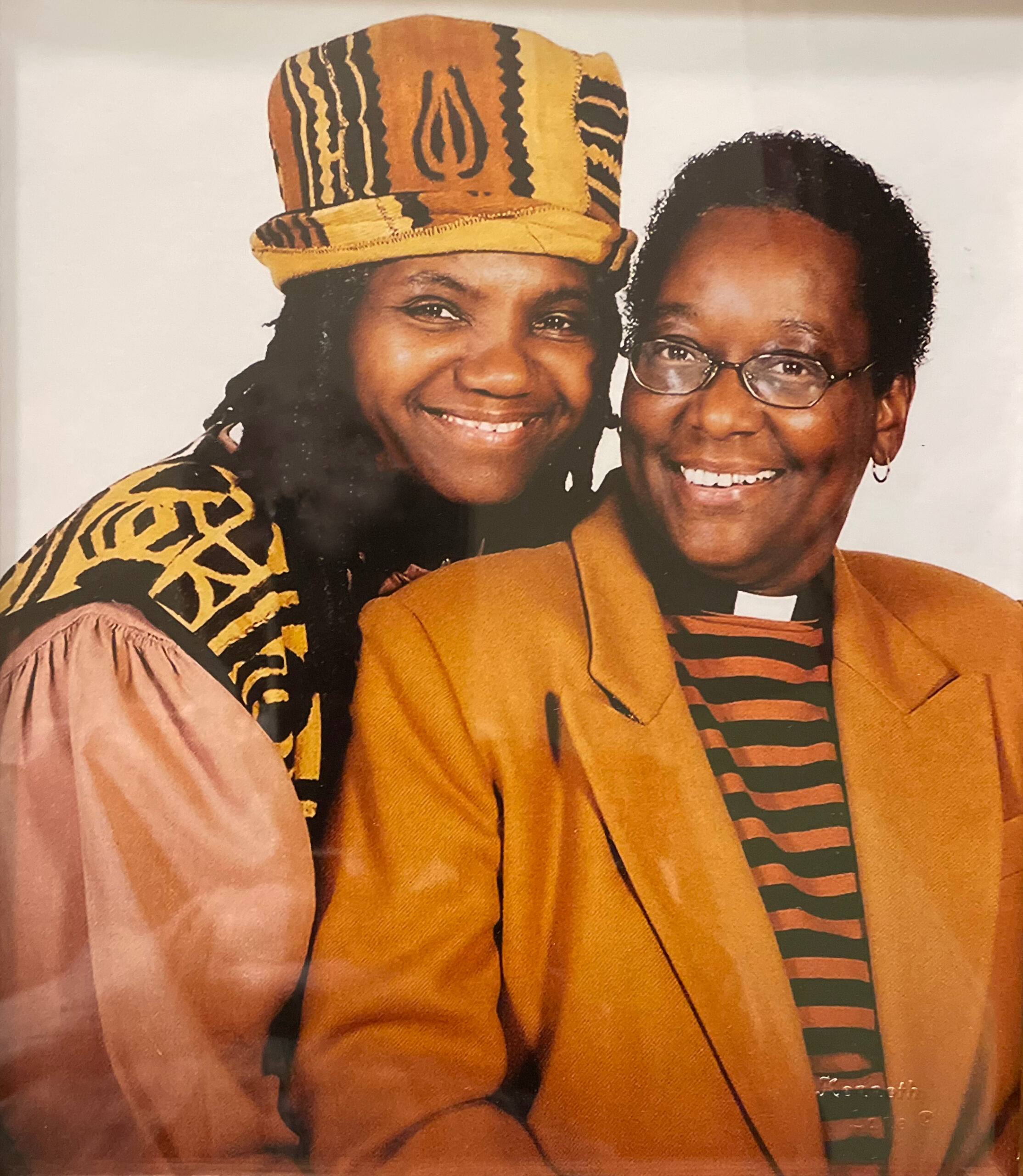

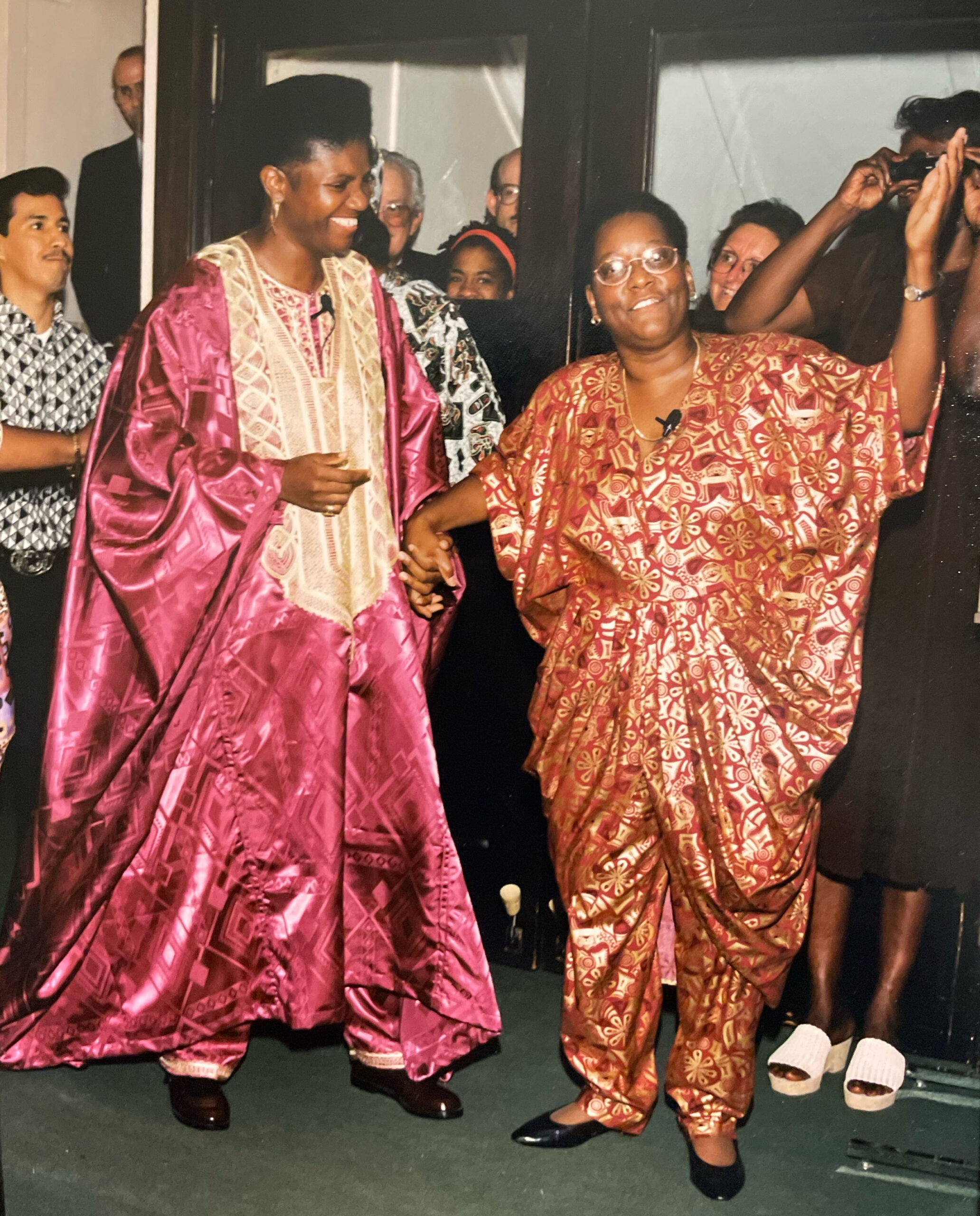

With her powerful voice, Rev. Mobley-Bowie has led protesters and congregants in song; see and hear her at this candlelight vigil for Matthew Shepard and during this 2015 MCC service. You can hear more of her on Doug Gazlay’s 2011 recordings. Rev. Mobley-Bowie currently serves as minister of music for the Breath of Life Spiritual Center MCC in Saginaw, Michigan, where her spouse, Adrain Mobley-Bowie, is the founding pastor. Hear them both sing here or listen to a service they led together for Kwanzaa.

The Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History houses a small collection of Rev. Mobley-Bowie’s papers.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History.

It was late December 1990 and I’d just finished reading through the first draft of my Making Gay History book. I’d promised to have the manuscript on my editor’s desk the following month. At a hefty 800 pages you’d think it was plenty comprehensive, but then it hit me: I’d meant to include the oral history of someone who had been involved with the Metropolitan Community Church. Meant to, then forgot.

The Metropolitan Community Church, or MCC, was a church by and for gay people founded in Los Angeles in 1968 by Rev. Troy Perry. It had played an enormously positive and important role in the lives of Christian lesbians and gays and had been a high-profile fixture in the movement during the 1970s and ’80s.

The oversight left me scrambling to find someone on my list of potential interviewees who fit the bill. A search for “MCC” led me to Rev. Carolyn Mobley, who’d recently joined MCC of the Resurrection in Houston as assistant pastor. And, lucky for me, she was up for a chat.

Rev. Carolyn, it turned out, was as comfortable explaining the Apostle Paul’s letter to the Romans as she was leading protesters in chants and song. In the 1980s, she’d become a prominent LGBTQ activist in Atlanta, working as an early AIDS educator and advocate, and as a founding member and the first female co-chair of the African American Lesbian and Gay Alliance.

But Christian education had been an early calling, and by the time I interviewed Rev. Carolyn, she’d moved from Georgia to Texas to serve her longtime church, MCC, in a professional capacity. With my deadline looming—and the travel budget for my book long gone—Rev. Carolyn and I made a plan to speak by phone.

So here’s the scene. It’s a cold night in San Francisco. I’m at my desk in my poorly insulated apartment on Filbert Street with a blanket around my shoulders. I set up my tape deck and plug in a small switcher box that lets me record directly from the phone. I dial Rev. Carolyn, who picks up at her one-story cottage in the Braeswood Place neighborhood of Houston. I start by asking her about her childhood in Sanford, a small town in central Florida, where she was born in 1948 into a family of educators.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Carolyn Mobley. Saturday, January 26, 1991. Interview is by telephone. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Location of the interviewee is Houston, Texas. Tape one, side one.

Did you have any sense growing up that you were different in any way?

Rev. Carolyn Mobley: Certainly.

EM: How so?

CM: Well, I was a kind of typical tomboy and then even before I started school, I, um, always had a fascination for, um, older women—and girls, too, but mostly people who were my babysitters or teachers, uh, stuff like that. Always fascinated with women teachers. I mean, having a crush on them, you know.

EM: Hmm. Does anyone in particular stand out?

CM: Oh, yeah. Um, there was a woman named Hortense who was, uh, my first babysitter and she kind of helped watch out for us a lot up until second grade—maybe a little after that, third, fourth grade about—but, um, I was definitely in love with her all of my life.

EM: Can you characterize what that feeling was?

CM: Well, I used to have this recurring dream about this particular woman, uh, and I’m talking as early as the first grade. I would dream that I was, uh, that she was going out on a date. And somehow during the date, her—the man she was with would begin to attack her, or what I thought was an attack. She seemed to have been struggling and I would just fly out of the sky like Superman or Super-woman or somebody, and just beat the poor guy to a pulp and then take her off in my arms, just flying away like Superman, you know? It was really wild.

EM: That is wild.

CM: And it was a recurring dream for years and years and years. And it was only this woman that, that I would rescue—never a faceless woman or other women that I knew, just her. I never quite figured out what it meant other than I was in love.

And, and I had a sense, um, even in the fifth, sixth grade that I always liked girls better than boys. I didn’t, want to be playing house and mommy and stuff unless it was all girls and I got to be the daddy. So it was like, um, always this attraction for females that I, as I got older and began to, to understand that it was shunned—I mean, like, I used to tell my mother, “I’m gonna marry a girl when I grow up.” When you’re real small, I could get away with it, but by the time I got to fourth, fifth grade, you know, I was told not to say that anymore.

EM: Right. But you knew.

CM: But I knew, for sure.

EM: Hmm. Did you also know that you wanted to, uh, become involved in, in, uh, in religion, in any way?

CM: Yeah, that was happening simultaneously in me as I was growing up. I did have a sense of wanting to work in the church and, uh, knowing that, that, that was where I felt, uh, most complete and satisfied.

EM: Did you go to church as a kid?

CM: Oh, yeah. My grandfather was a Baptist preacher and the whole family was church-minded and active in the church.

EM: Can you describe your church where you grew up for me?

CM: It was a typical Black Baptist church, fairly, um, emotional in its expression, but I was blessed to have some really good pastors in terms of knowing the scriptures and being excellent teachers. Church was a real, um, social fabric of my life and community. I mean, you just didn’t think about not going to church. It was an understood reality. For me, um, being kind of a serious-minded kid, it was more than just getting into the routine because I took it seriously and I, I do have a strong faith, and I remember at age 10 basically deciding that I wanted to be on God’s side in the world.

And it’s been a firm faith for me. And it’s been something that I’ve never wavered from, even when I began to feel some tension between my belonging to Christ and my being a lesbian.

EM: What was life like in your town? Was it a segregated town?

CM: Very much so. In the first place, when I was really small and, you know, elementary school, it was just like, that’s the way it was. To me, white people weren’t real. They were only on TV, like cartoon characters. I didn’t know any, I wasn’t going to a white school, you know, we didn’t, we shopped in the Black neighborhood, there were Black grocery stores. Um, and so there was like this real segregation, a separation. And, I mean, white people just seemed unreal to me. When things began to change, uh, I began to be aware—I remember when they built the civic center in downtown Sanford, um, and there was a downtown swimming pool built, uh, I guess this was in the ’60s, maybe late ’50s.

And I remember it being a really big thing that no Black people could go in the civic center. That became a real issue, um, in terms of kids my age knowing about it and wanting to use the swimming pool and not being able to, um, you know, and it was like, gosh, well, what is this and why?

EM: Didn’t—that must have struck you as very bizarre.

CM: It did. It did. Um, and, and maybe it was just coming into consciousness of it, because all of a sudden I was aware of things I couldn’t do, or weren’t supposed to do. Something that happened to me, I’m sure I must have been about 11 or 12. My mother was going to summer school in Tallahassee, Florida, for many summers. And, um, one summer—I don’t remember which one it was, but it was seemingly after my father had died—he died when I was 10, so this must’ve been like a year or two later.

But my cousin, uh, and I had taken a bus, Greyhound bus from Jacksonville to Tallahassee, where she was gonna spend a couple weeks with me and my mom. And not thinking and not paying attention to much of anything, we got off the bus in the bus station and looked around and we saw a sign that said “Waiting Room.” So we went in. We weren’t, had never been there before—we hadn’t been on the bus before—so, you know, it was like, everything was new.

Well, honey, we were sitting around in there looking, and all these white people, you know, were sitting around, and then we noticed this cop walking up and down in front of us, you know, kind of with his hand on his billy club. But we didn’t pay much attention and really was just unaware of what was the staring about.

So my cousin went up to the counter to buy some Life Savers, and the lady told us, “You know what’s good for your Black ass, you’ll get the hell out of here.” So she jumped back and came over and told me, and I said, “What?” You know, I couldn’t believe it. Then we got scared. So we decided we better go out the front door. And as we did, we saw this sign on the other side, as we were walking up and down in front, that said, um, “Colored Waiting Room.” And I said, well, I’ll be damned, you know?

But that was the first direct kind of, uh, impact upon me, uh, on my own person and life and experience of somebody telling me that I couldn’t do this because I was Black or that I was fixing to get beat up or put in jail or something because I was in the wrong place.

And it kind of freaked me out. Now, like I said, I must have been about 12 then.

EM: And then, and then to become aware of, of another difference in you.

CM: Yeah, really. Um, and, and to know later on, of course, that that could put me in equally threatening situations if I weren’t careful and mindful.

EM: Hmm, so were you careful and mindful of keeping that a secret?

CM: Oh yeah. Oh yeah. Um, mostly because I felt in conflict about it the older I got. I began to be aware of words in scripture. And, um, of course, as a 16-year-old reading the Bible myself, um, almost the only way you can take stuff is literally unless you have some other insight. And so naturally I was aware of, of, of, uh, what was in Romans, his first chapter about God giving up on people and giving them over to a reprobate mind, which no—only God knows what a reprobate mind was—but, um, the description of, of people giving up normal—quote, unquote—sexual relations for being with people of the same sex. And so I felt condemned by that, uh, initially, and decided, well, gosh, if that’s wrong, I just won’t do it. You know? And so I was praying God would change my feelings and just take the desire away to be with females. Um, and to just let me be more open to, um, having a boyfriend and being with guys.

Well, I dated, as it were—wasn’t really dating. It was like, this boy walked me home from school most days. And sometimes he would come over weekends and we’d sit and watch TV, but there was—he would always end up wanting to neck and stuff and it was like, oh no, this is, you know, I know God didn’t want me to do this. I mean, it’s one thing for me to sit here and watch TV with you, but no, no. So that became some pressure. But at the same time of course there was these hormonal changes going on and some sexual arrousal was happening even, uh, with a guy.

EM: Right.

CM: But it was like, I knew I didn’t want to screw him.

EM: Right.

CM: And I was certainly aware that I could get pregnant and mindful of I didn’t wanna be having no babies. So that was just out for me. It wasn’t even a consideration.

EM: Right. Well, thank god for God.

CM: Yes. Oh, goodness. But, you know, it’s funny that my sisters—my older sister, who’s only 11 months older than me and my younger sister—were both, um, already having sex in high school and unbeknown to me my mother had pulled them aside and put them on the pill and—but she never did that to me.

EM: Why did she not put you on the pill?

CM: Honey, my mother knew I didn’t need to be on it. She knew my legs were not going open. And I asked her that one time when I came out to her, she said, “Well, I thought that you was strong enough to not be doing that.” So I said, well, okay. But it just let me know that mothers do know.

EM: Yes.

CM: They always know. But what was happening with me was that I was beginning to feel this guilt. So I, I stopped any contact that was real close with girls in terms of writing letters and, you know, spending the night over at anybody’s house or stuff like that. By the time I graduated high school, um, I did spend the night with one girl that, uh—we kissed and stuff in bed and I just really got freaked out and I thought, okay, that’s as close as I come. All right, Lord, never again.

So, uh, the very next year I went all the way from Orlando, Florida, to Abilene, Texas, to go to college, to get away from the pressure of this particular girl and, uh, found out of course that I took all those pressures with me and that they were internal. And I would fall in love with other girls.

EM: What school did you go to in Abilene?

CM: Hardin-Simmons University. It’s a Baptist school. By that time I had decided I wanted to be in church work. And girls could not wear pants on, on campus, and there were curfews, and, you know, there was no smoking on campus, no drinking, uh, all of this really clean-cut American kids, right? So I said, well, this will certainly help me maintain my commitment here. It was a small college, you know—it never had 2,000 students the whole time I was there.

EM: Boys and girls?

CM: Mm-hmm. Co-ed. Um, but I was the only Black, uh, female in my freshman class.

EM: What was that like?

CM: Uh, very different, but for me good. Probably people, you know, went out of their way to be kind to me and to—I never had any negative incidences where people put me down or called me racist names, or, you know. People were just really, uh, making an effort to—it was almost like that syndrome of, oh boy, we gotta make up for all this shit that’s happening in the world.

EM: Hmm.

CM: And of course Dr. Martin Luther King’s, uh, assassination my freshman year made that kind of come to a head for me. We had a—the only negative confrontation was a very mild one. There were a number of Black male students, uh, mostly on basketball scholarship, and after King’s assassination—that was in the spring—we decided to go to the president of the university and ask him to lower the flag at half-mast like it was being done all over the country. And he had initially said that they wouldn’t do that. So, you know, we had to do this protest, and finally he agreed to lower it, you know. It was like, that began tensions on the campus.

So we began a series of dialogues, which were very helpful. And, uh, for the first time, people’s racism began to show itself. Uh, one girl in particular that I had, was friends with, I thought, you know, started talking about, “Well, he had it coming,” and, you know, “Maybe it’s best anyway,” and just all the negative, uh, lies and falsehoods that Dr. King was an instigator of trouble and a communist and, uh, you know, the worst kind of American. And it’s like, I couldn’t believe it, that these college kids thought this man was a bad person.

EM: How did you see him?

CM: I saw him as a saint. A man of God, first of all, uh, whose, whose life was devoted to God and, and to peace. I certainly understood that he, um, knew the difference between right and wrong and good and bad.

Um, his thing about disobeying unjust laws. I mean, I began to, to take seriously, to think seriously, about, um, things that I was told to do. Are they really right? And does somebody who’s in authority telling you to do it make it right? If it’s wrong, it’s wrong. Even if the president of the United States tells you to do it.

So, you know, to begin to think more seriously about the, um, inherent goodness or evilness of a thing or a law or a cause more than who is saying it. Uh, and it began to really change my way of looking at myself and the world. And it certainly helped me to reevaluate then, uh, the message of the church that I was getting about homosexuality. And, uh, even as a college student, uh, reading scripture continually on my own and rereading especially Romans numerous times, I finally got the picture.

EM: Which was?

CM: That God was not against homosexuals. That even if the person who wrote that particular passage in Romans, namely Paul, was against homosexuals, he was a human being subject to error, just like me.

And so it’s like, I think the man is wrong, period. So it doesn’t matter who says it, if it, if, if what he’s espousing is inaccurate, it needs to be challenged. So that came directly from my beginning to sense that that’s what Dr. King was about, challenging error wherever it was found.

EM: Hmm. Well, what could you do about that once you saw that it, that, that Romans was not right?

CM: Um, begin to, um, live my own life, number one. That I had to stop, um, accepting the error for me, so that by the time I finished college, I was ready to become a sexually active adult. And as I began to come out to me, I came out to my mom right away the very first year I was home after college.

EM: That would be 19—

CM: ’71.

EM: Uh-huh.

CM: And, um, I had my first sexual experience very shortly thereafter.

EM: Well, what did your mom say?

CM: When I told her that I thought I might be a lesbian, is the way I put it? She didn’t say a whole lot. She kind of, uh, got teary-eyed and then she said, “Well, you know, maybe you should see a psychiatrist.” Didn’t know what else to say, so I said, “Well, maybe I’ll do that.” Then she said, “Well, maybe you really ought to just get on birth control pills, and you’d feel freer to experiment with men. And, uh, you might discover you’re not after all.”

So I said, well, you know, I really can’t knock it till I’ve tried it. So maybe I owe her or the universe that. So I got on the pill. I did go to a psychiatrist. I had an appointment with a shrink in Orlando, and it was like, no, no, no, no, this is not the route for me. So I just didn’t go back.

Um, in the meantime I did decide that I would have sex with a man. And I thought it would be more than once. I really thought I would try this several times and just see if it made a difference. Um, and I tried it once, and this was with the boy who was my boyfriend all through high school. And it was like, this is a joke, you know? I couldn’t believe I was doing it, and it was totally unsatisfying and I thought, well, so much for that. I don’t think I need to do this again. So I decided, um, the natural way is the best way.

EM: Mm-hmm

CM: What seems natural is, you know, my—to follow my own instincts and my desires. And I also began to reinterpret further that whole Roman scripture about giving up what was natural for something unnatural. And it played right into my own consciousness that, you know, Paul had a point: that it is unnatural for me to screw a man and I won’t do it again! The only natural thing for me is what I’ve been feeling since day one in the world. And why would I try to change that? How foolish I’ve been! You know, and it’s like, well, thank you, Paul. I got your message, brother. You know, we okay. And it, it just, it was like a light going off in my head, uh, that this, his argument in terms of what is natural really does make sense. But you have to know what’s natural for you.

EM: So the guilt, the guilt left you then.

CM: Oh, definitely. And, and it’s like, that’s what truth will do for you. It sets you free. God delivered me from the guilt and shame and gave me a sense of pride and wholeness and, and all of that stuff that really I needed.

So by the time I got to, uh, seminary, I had made some decisions about being a lesbian, that I didn’t want to live a double life in terms of having to hide that part of myself. So I began to investigate MCC.

I had read an article, I think, in TIME magazine, or Newsweek maybe it was, about this new gay church that Troy Perry had started. And, uh, it was a fairly negative article, but even negative press is good press when the right people read it.

And so I was just impressed that there was such a church. And I said to myself, I wonder what that would be like to have a gay church, you know, what a neat idea. So as I got to Atlanta, who would be in my entering class, but the assistant to the pastor at a local MCC. He was the only white man in the school— student—and he was the only announced gay man in the school.

I went to a Black seminary deliberately because I had gone to a white college and I thought, well, I need some balance in my life, too. This was ’72-’73 school year. So there he was, an entering student, there I was, an entering student, and I thought, well, I’ll be darned. So I started talking to him right away and he was telling me about the church and invited me to visit, and I was not quite ready to go. I thought, hmm, well, wait a minute, I, I have to think about what I’m gonna do here, career-wise. Is this a good move?

EM: What were, what were you fearful of?

CM: Um, there was still this major stigmatization, uh, in the, my community as a Black person. And I was aware that, that if I wanted to work in the Black church, that I, it would mean not being out.

But then I fell in love with a woman who was working at the same mission center as I was—we were both doing student internships the second semester. And by the time I moved in with her, it was, that was when I first went to the church. We went together.

EM: To MCC.

CM: MCC. I had joined a Black Baptist church, but as I, uh, got into this relationship, I wanted to go to, to church somewhere where she could be with me and both of us feel comfortable, uh, and that wasn’t happening at a Black Baptist church. This was a white woman, too.

EM: Mm.

CM: So we went to MCC. She had been going to a Catholic church prior to that, uh, so this was a compromise for the two of us. And, uh, we felt a little strange because it was just so different from anything we had experienced before. Very different from Black Baptist churches. And even though it’s akin to Catholic mass, it was still very different for her. This was a Protestant minister up there. And, uh, most time they just wore a clergy collar and, and jeans or whatever they wanted to wear, you know—it was a very casual and laid-back church, which we liked, you know, and felt really drawn to it, uh, fairly quickly and did get involved in the church fairly quickly within a few months.

EM: Were there a lot of people in the church? How many people would you say?

CM: The church at that time was under a hundred people, but it was a strong, um—more than 50, 60, 75 or so. And it was growing.

EM: Was it men and women both?

CM: Men and women. Even though it was largely, uh, white male, there were a few Blacks. There was two, three Black men. There was me, and maybe one or two other Black women visiting from time to time. So it was, it was a good mix.

EM: How, how much of a role did MCC play in your life at this time?

CM: Tremendous. Because I was constantly coming out, uh, to myself and getting more comfortable with that and deciding that there was a way to really be out in the world. Even though this church was just a, uh, almost an oasis, you know, in the desert. Uh, it, it provided me with a place where I was totally accepted as a lesbian and a Christian, that there was never any question about how the two could coexist. So that by the time I graduated from seminary, I was encouraged to pursue, uh, credentialing, uh, to become a minister in MCC.

But my stronger sense of call was still to be serving the Black community. So I had the tension that, you know, why should I serve a white church primarily, even though it is a gay church—that somehow the bigger commitment was to serve the Black community. I mean, I was, I’m conscious even now, and I have been all along, of the fact that I belong to a people that I couldn’t just abandon.

So I had the opportunity when I finished seminary to be employed by Southern Baptists, which is a predominantly white Baptist denomination, but the job they wanted me to do was going to put me in the heart of, uh, low-income public housing communities doing Christian education, minority outreach, um, and building disciples among minority peoples.

EM: How did you like your job?

CM: I loved it.

EM: My notes here say that you were asked to resign ultimately.

CM: Right. Ultimately. But, see, in the beginning, um, no one asked. I just figured they knew when they hired me. What I think ultimately led to my resignation, I, um, did not cover myself in terms of bringing a man to functions. You know, some people know that that’s expected and they do that. So if you’re having a luncheon or a staff dinner or Christmas party, and you’re supposed to bring a guest, they expect you to bring a opposite-sex guest. Well, I never did the whole five years I was working there.

But it’s neither here nor there to me, because it’s like, that was, I knew when I took the job that ultimately it might come to that. And whether it was an incident or just, uh, my getting fed up with the homophobia in general, it was just time. You know, I was ready to, to get off that bandwagon and so, um, I didn’t pursue any recourse, and because I willingly left, um, the Home Mission Board decided that they would pay me full salary for six months.

So I basically used it as a time of, um, rest and recuperation and reflection and renewal and, you know, turning it around. I joined MCC immediately the Sunday after Easter.

EM: You became an official member.

CM: Official member, right. ’Cause I had been a friend of the church all that time. And so I joined the church in ’81, became a member, and decided, uh, maybe I would move toward becoming credentialed clergy, uh, in the Universal Fellowship of MCC.

EM: And here you are.

CM: Here I are.

EM: What, what do you see as your place in, in this, in, in the, the gay and lesbian rights movement?

CM: Um, I’m settling down to commit to a place of ministry. Before, I think I saw myself more as an activist and I, and I know that ministers, especially in the Black tradition, can be, and often are, activists as well.

Dr. King was a minister first whose ministry led him into activism. Same thing is true for Jesse Jackson. He is a minister first. Um, the same thing is true for Andy Young, who went into politics as his activism. Um, I have chosen ministry and I believe that the rest of my life will be devoted to that, that that is the way that I’ll make my contribution.

———

EM Narration: Rev. Carolyn continued to minister at Houston’s Resurrection MCC for 15 years, first focusing on Christian education, then pastoral care, and finally community partnerships. During that time, she served on the city’s AIDS Task Force and volunteered as chaplain at a local home for the care of people living with AIDS. In 1993, Rev. Carolyn was elected to be grand marshal of the Houston Pride Parade.

It was in Houston that Rev. Carolyn also met her life partner, Rev. Adrain Bowie. In 1998, they affirmed their relationship with a service of holy union in front of 300 guests—including both their mothers. The couple legally married in 2015 and took each other’s last names.

Rev. Carolyn Mobley-Bowie is now semi-retired and lives in Saginaw, Michigan, in the house where her spouse, Rev. Adrain, grew up. Rev. Carolyn works part-time for Visiting Angels, providing home care for seniors, and is serving a three-year term on MCC’s Council of Elders. For the past four years, she’s been the minister of music for the Breath of Life Spiritual Center MCC in Saginaw, where her spouse is the founding pastor.

The Metropolitan Community Church continues to be a spiritual haven for Christian LGBTQ people. It now has 222 member congregations in 37 countries.

———

Thank you to my Making Gay History colleagues, including producer Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Cathleen Conte, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Thank you also to sound engineer Casey Holford for providing guidance on how to improve the audio quality of the phone interview.

Special thanks to our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

And thank you to the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division for their assistance with photos and other images.

Season eleven of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation; Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS; the Calamus Foundation; Christopher Street Financial; Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson; Louis Bradbury; David Quirolo; Lee Schere; the Danser family; Andra and Irwin Press; and Greg Adgate, who made a donation in honor of his daughters Anna and Grace.

Head to makinggayhistory.com where you’ll find all our previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

And don’t forget to join our new Patreon community. For $5 a month, you’ll get access to exclusive content and you’ll support our mission to bring LGBTQ history to life through the voices of the people who lived it. This week, we’re adding video of my recent catch-up conversation with Rev. Carolyn and a bonus clip of our original 1991 interview. Find out more and sign up at patreon.com/makinggayhistory or go to makinggayhistory.com and click on the Patreon link in our banner.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###