Craig Rodwell

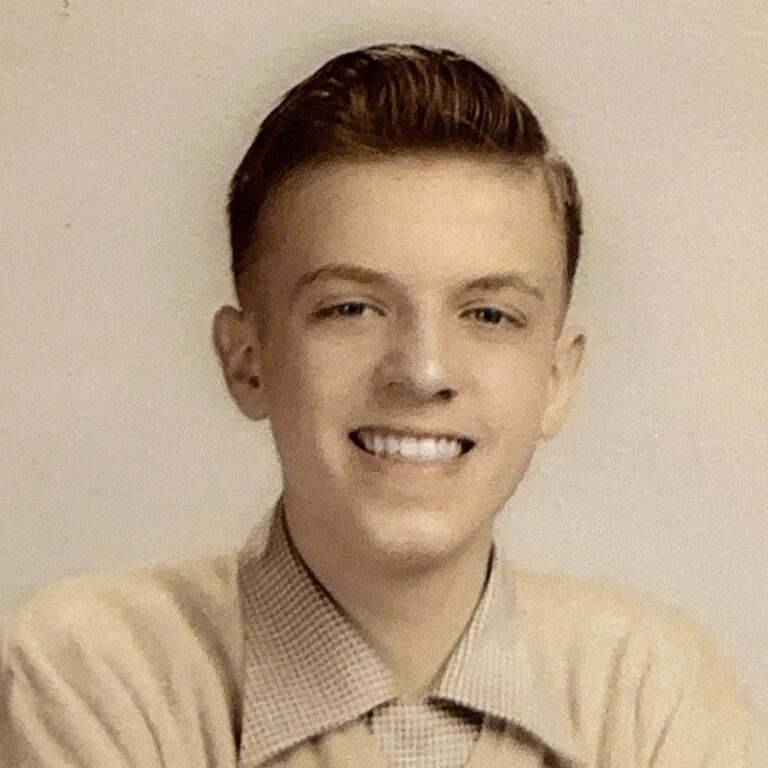

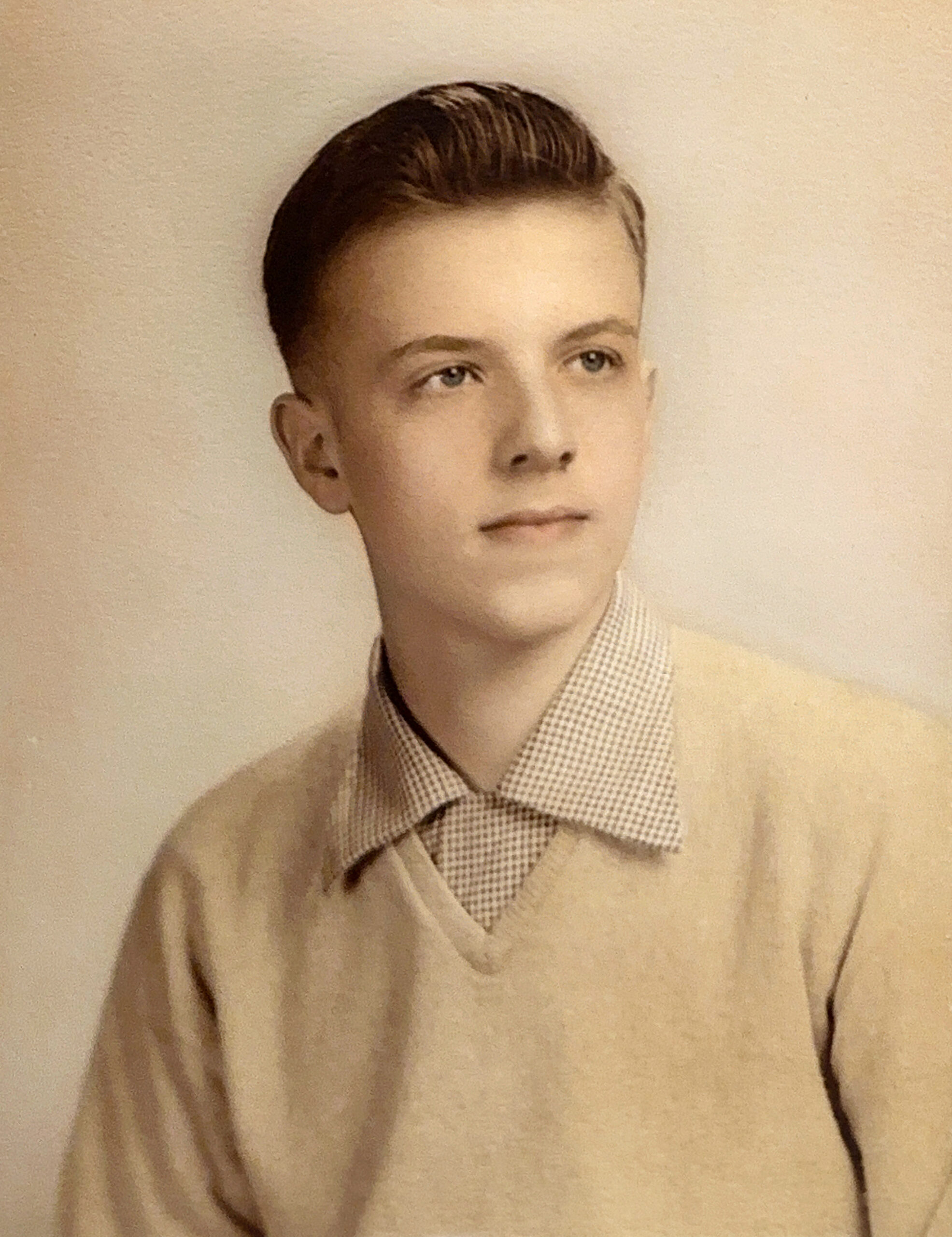

School portrait of Craig Rodwell, Sullivan High School, Chicago, mid-1950s. Credit: Craig Rodwell Papers, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

School portrait of Craig Rodwell, Sullivan High School, Chicago, mid-1950s. Credit: Craig Rodwell Papers, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Episode Notes

In 1954, Craig Rodwell was just 14 when he was arrested for having sex with a man. The experience set the young Chicagoan on the road to becoming a self-described “angry queer”— and one of the most consequential LGBTQ rights activists before and after Stonewall.

Episode first published November 3, 2022.

———

Craig Rodwell was a gay rights pioneer in both the pre-Stonewall homophile movement and the 1970s post-Stonewall gay liberation era. For an overview of his life and work, read this in-depth profile or watch this short video.

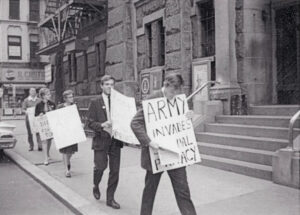

Rodwell participated in several of the earliest LGBTQ rights demonstrations on record. In 1964 he picketed—alongside activist Randy Wicker—in front of the U.S. Army Induction Center on New York City’s Whitehall Street to protest the Army’s failure to keep gay men’s draft records confidential.

In 1966 he took part in the Mattachine Society’s historic Sip-In at Julius’, a gay bar in Greenwich Village; you can hear more about it from Rodwell’s co-protestor Dick Leitsch in this MGH episode. Rodwell also conceived and participated in the iconic Fourth of July Annual Reminder pickets from 1965 to 1969 at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. Despite the required conservative dress code and strict rules of conduct, these protests were part of a radical shift toward direct action for gay and lesbian civil rights.

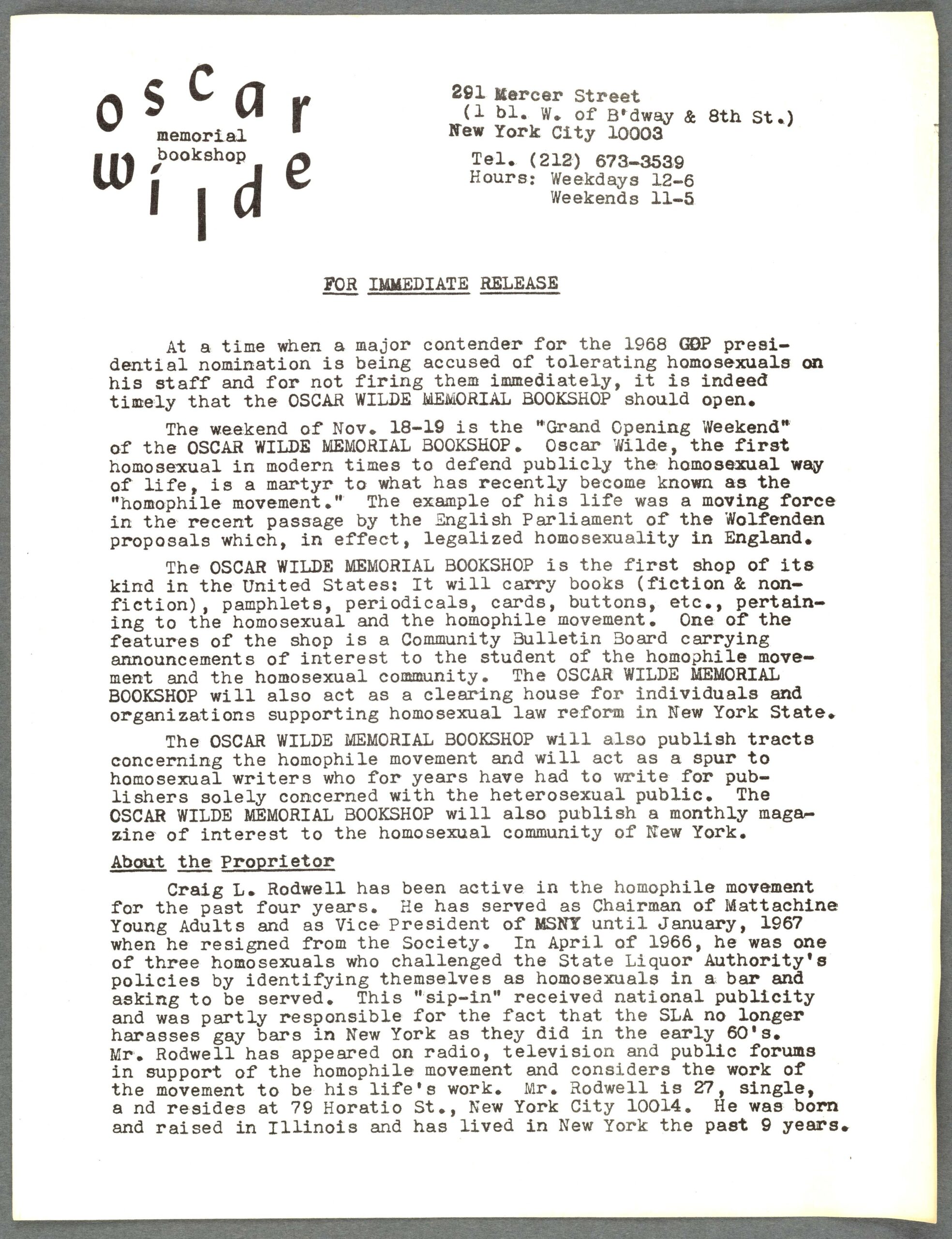

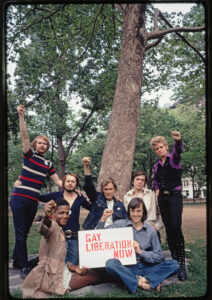

In 1967, Rodwell opened the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, the first openly gay and lesbian bookstore on the East Coast. That same year he founded the Homophile Youth Movement in Neighborhoods (HYMN) and began publishing its newsletter, HYMNAL. In the wake of the Stonewall uprising, Rodwell led the effort to organize the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, the precursor of today’s Pride parades, marches, and celebrations; find out more in this video. Hear Rodwell discuss his early activism, his bookstore, and his memories of the Stonewall uprising in this MGH minisode.

At the conservative boarding school Rodwell attended from age six to 13, his exposure to the outside world was strictly limited. But as he notes in the episode, on Friday nights the students were allowed to watch Mama. Get a feel for the old series and the social mores they imparted here and here.

Teenage Rodwell cruised the streets of Chicago for sexual encounters with men. He met Frank Bucalo on the corner of Dearborn and Division, better known by gay men in the the 1950s as Quearborn and Perversion. He met Harry Dilworth on Oak Street Beach, a meeting spot for gay men since at least the 1930s. For a little more LGBTQ Chicago history, visit this online exhibit from the Gerber/Hart Library & Archives. For a deeper dive, read Chicago Whispers: A History of LGBT Chicago before Stonewall by St. Sukie de la Croix or watch the documentary Out & Proud in Chicago.

Back at Dilworth’s apartment, Rodwell learned that his new friend subscribed to ONE Magazine and the Mattachine Review, the first nationally distributed gay and lesbian publications. You can explore the entire run of ONE Magazine for yourself here or check out more than a hundred issues of the Mattachine Review here.

Rodwell got cruising pointers from a Northwestern University student who had picked him up on the street. A decade later, the 1964 publication The Beginner’s Guide to Cruising might have served as a handy resource. For those with a bit more experience, there was also an advanced edition.

In the episode, Rodwell mentions being out after curfew. In the 1950s, curfews were enacted for unaccompanied minors in an effort to curb juvenile crime in cities across the country. Similar laws continue to crop up, even recently in Chicago, despite their poor track record.

Rodwell’s fellow arrestee Bucalo would have been in violation of Illinois’s sodomy and age-of-consent laws. For a broad history of age-of-consent laws, see Jailbait: The Politics of Statutory Rape Laws in the United States. For a history of Illnois’s sodomy laws, go here. In 1962—nearly a decade after Rodwell and Bucalo’s arrest—Illinois became the first U.S. state to decriminalize homosexuality by repealing its sodomy law.

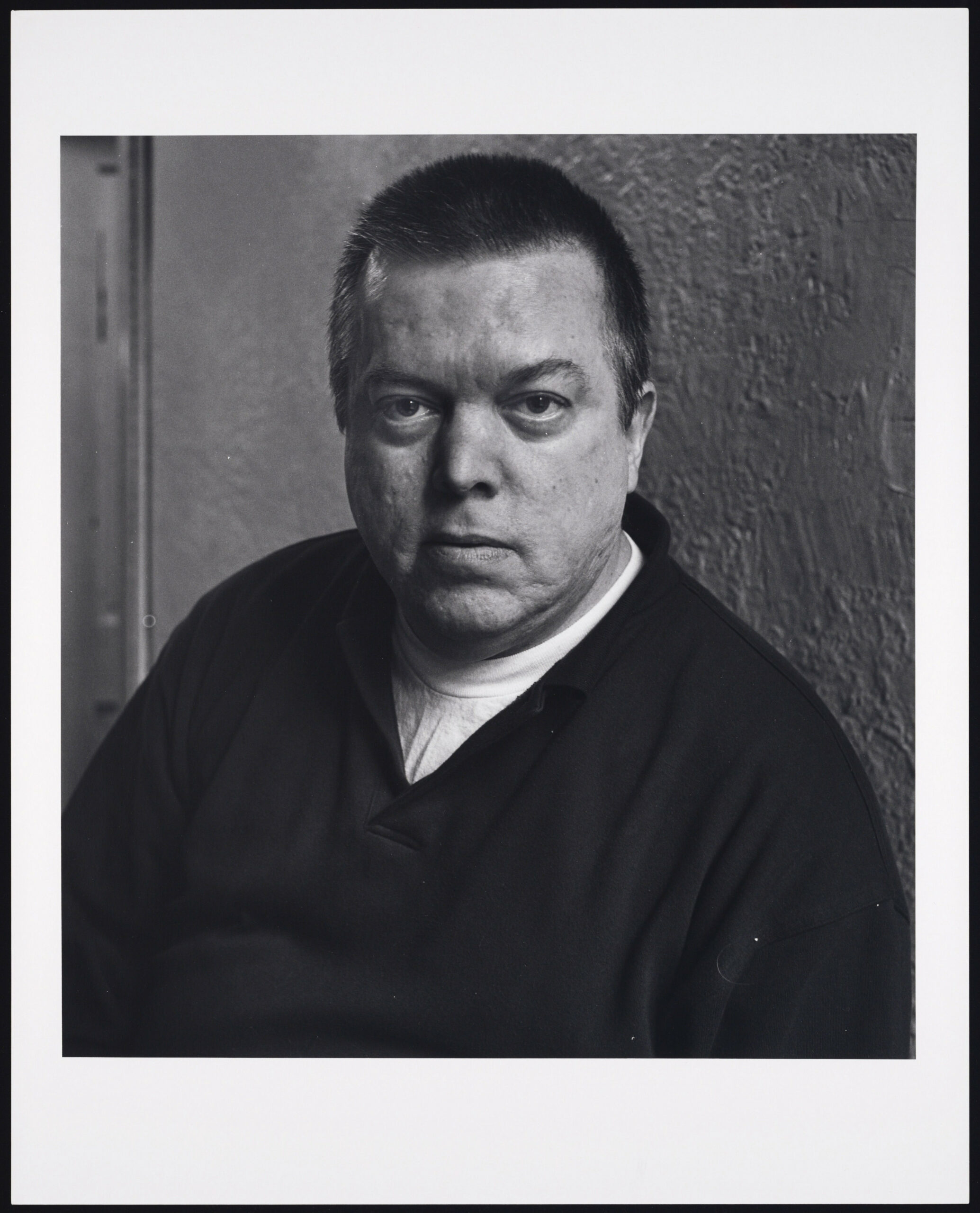

Rodwell died of stomach cancer in 1993 at the age of 52; read his New York Times obituary here. The Craig Rodwell Papers, a collection of his letters, files, photographs, artifacts, and sound recordings, are housed at the Manuscripts and Archives Division of the New York Public Library.

———

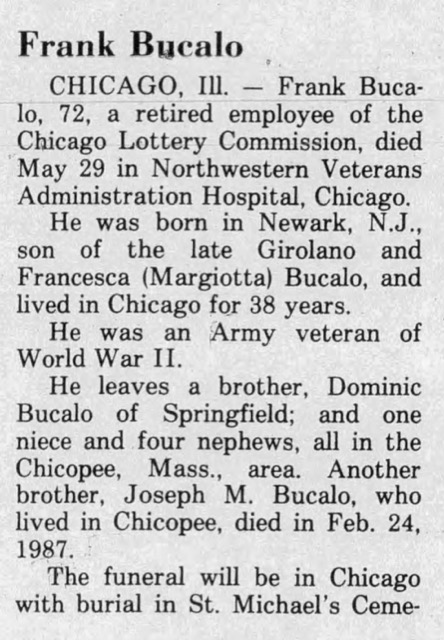

March 2023 postscript: At the time we recorded the episode, we’d been unable to find out what had become of Frank Bucalo. However, MGH listener—and ace researcher—Fred Maxon has since unearthed some information about the man who was likely Rodwell’s fellow arrestee.

The obituary below, which was published in 1988, describes a Frank Bucalo who lived in Chicago, where the arrest took place, for nearly four decades. It suggests he was never married and didn’t have children.

V.A. records confirm that Francis J. Bucalo was a World War II veteran born on October 16, 1916—which means he was, as Rodwell notes in the episode, in his 30s in 1954, the year of the arrest. Bucalo likely moved to Chicago sometime between 1950 and 1954. Records from the 1950 census show a Francis J. Bucalo (whose place of birth and age match the details in the obituary) living in New York. The census records list his profession as “Counterman—Restaurant,” similar to dishwasher, the job that Rodwell said Bucalo held.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

If you’re a regular listener, you’ve already heard Craig Rodwell’s name and voice in several past episodes. That’s because he was one of the most consequential, fearless, and visionary activists of the 1960s and early ’70s. The country’s first gay rights protest on record, in 1964 in front of New York City’s Whitehall Army Induction Center, Craig was there. The landmark 1966 Sip-In at Julius’, the legendary gay bar in Greenwich Village. Check. The annual Reminder Day protests in Philadelphia. Check.

Then in 1967 Craig opened the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, one of the first gay bookstores in the world. It quickly became a hub for gay rights organizing in New York City. And to mark the first anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, he co-organized the inaugural Christopher Street Liberation Day March in 1970—the blueprint for the Pride marches and celebrations now attended by millions of people around the world each year.

And all of that before he celebrated his 30th birthday.

But then, Craig’s radicalization had begun very early. As you’re about to hear, he traced back its roots to a night of cruising in downtown Chicago when he was 14 years old. A night that ended in his arrest. Fair warning: in this episode Craig paints a picture of gay cruising life in the 1950s—the choreography of it, the danger of it, and, for young Craig, the consuming thrill of it. Craig was precocious in every way, and in his account of his early sexual adventures, he sounds completely empowered. But for all of Craig’s sex-positivity, he was just a young teenager at the time. If hearing about that will make you uncomfortable, you may want to give this episode a pass.

So here’s the scene. I meet up with Craig at his bookshop, just down the block from the Stonewall Inn. It’s in an old brick row house with a short stoop and a picture window filled with books overlooking Christopher Street. The circumstances are less than ideal: I have a terrible cold, and Craig has a train to catch and has just an hour to spare. But we cover plenty of ground: Craig’s a talker, and he’s got an arsenal of stories at the ready for me.

We start at the beginning. Craig, who was born in Chicago in 1940, was just an infant when his parents separated. As a single working woman, his mother struggled to provide care for her young son, so she sent him to a small Christian Science boarding school northwest of the city. I ask him what life at the school was like.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Craig Rodwell, February 17, Friday, noon. Location: Craig Rodwell’s store, the Oscar Wilde Bookshop, New York City. My name is Eric Marcus.

Craig Rodwell: Well, it was officially an institution for problem boys. Um, I never fully understood why I was there. I mean, I’ve always been sort of a problem. Anyway, I lived there from age six to almost 14, and it was an all-boys school, way out in the country. It was woods all around. It was a very hothouse atmosphere, we had no contact with the outside world. Um, except for television—on Friday nights, we were allowed to watch I Remember Mama, and they turned it off during the commercials even.

Uh, anyway, we, uh, we slept in dorms, bunk beds, about 15 of us in a dorm. And, you know, you got to be, like, 11, uh, many of us developed crushes on other boys, like heterosexuals that have the same kind of thing—

EM: So that’s where you first discovered…

CR: … my feelings, and they were very natural.

EM: Right. Understandably in that environment.

CR: Mm-hmm, it’s all of us that were…

EM: So by that, when, when you were 14, you already had a great sense of…

CR: Yes, of identity.

EM: Yeah.

CR: I thought the whole world was like me!

EM: Tell me what happened when you were 14 years old?

CR: That I was arrested?

EM: Yeah.

CR: Well, I would’ve been a typical, uh, evening. I went to live with my mother in, uh, Chicago during high school. I would’ve gotten home from high school usually around three. My mother didn’t get home from work till six. Um, and by then I, I’d developed a routine of, uh, I’d been out cruising for a number of months. I’d met this guy from, uh, Northwestern University student, and he told me the word “gay” and where to go—he picked me up on the street—uh, where the cruising areas were and what have you. So I was down there the next day. Literally.

EM: You were a precocious youngster then.

CR: Well, I guess that’s the word for it. Uh, I didn’t have Mommy and Daddy standing over me during my formative years telling me what to do and think. And we had the superintendents and house mothers in the institution, but they were more disciplinary figures. So I had a lot of mental freedom as a child to think for myself.

Uh, and my mother really had no control over me, even at that age. And two or three nights a week, I would get the subway—or the “L,” as we call it in Chicago—and go down to, uh, get off at, uh, Division Street, which was the major cruising area at the time. And just walk around the neighborhood to Bughouse Square and down Division and up Clark and Dearborn. For hours, sometimes I would walk around cruising, stand out in front of gay bars, …

EM: You couldn’t go in.

CR: No, no, but I’d stand out in front or across the street or down, couple stores down or something. And I met an awf—hundreds of guys during high school. Most of ’em were scared off from me when they realized how young I was. I always tried to look older and act older, uh, and I could pass for 17 when I was 13 or 14.

Anyway, I met this guy one night. I remember I was standing—one of my things would be, if I got tired of walking around, I’d stand, uh, at a bus stop, ’cuz you always had to watch for cops back then. If you saw a cop car, you know, you made sure you weren’t standing still for one thing. This is Chicago in 1954 I’m talking about right now. Uh, to the cops, homosexuals were just a step up from, uh, murderers. And we were treated that way. Uh, and they had total license and freedom to, to harass us on the street, make comments to us, hit us, whatever. Uh, so I would stand at a bus stop, and even then cops would stop occasionally and say, “What are you doing here?” You know. And I was, “Oh, I’m waiting for the bus.” That would be my excuse.

Um, anyway, I was standing at that bus stop at the corner of, Division and, uh, Dearborn. And this guy picked me up. His name was Frank Bucalo, a working-class dishwasher in his thirties, I think.

EM: How did he pick you up? How did he let you know…?

CR: He probably just stopped, looked at him, you know. Haven’t you ever cruised, honey?

EM: But my readers haven’t, though.

CR: Oh, okay. Well, you stand there, or when you pass somebody, when you’re walking, you look at them and they look at you and, uh, maybe perhaps you go a few steps and turn around and see if they’re looking back to see if you’re looking back to see if they’re looking back to see if you’re looking back. Uh, get the picture?

EM: Yes.

CR: Anyway. So I went to the guy’s, uh… He lived in a—what would we call an SRO today?—simple furnished room, uh, just a sink in the room, toilet down the hall. And, uh…

EM: Were you frightened?

CR: Oh god, no, this is, this is what I lived for, literally. And that’s all I thought about all day long, just so I could get downtown and go cruising. Uh, it was, oh, it was just, I get thrilled now even thinking about it, those, those, those times. It had a great sense of freedom about it and adventure and, oh, I met all kinds of guys—Air Force guys, cops, you name it. I met all kinds of guys during high school.

EM: So you went back to his room.

CR: Back to his room, had sex. I remember, it was very simple sex. Very sweet guy. I remember I washed my hands in his sink afterwards and there was some kind of soap that, I guess it had smell, perfume in it or something—I’d never come across that before. And I mentioned it to him and he insisted on giving me a bar of the—you know, still in the paper and stuff. And then he was walking me back to the, uh, the subway.

Oh, and I should add here that at that time in Chicago, there was a curfew. If you were under 17, you had to be off the streets by 10 o’clock unless you were with, uh, a relative.

EM: And it was past 10 o’clock.

CR: Mm-hmm, probably around midnight, something like that.

EM: What did your mother think with you being out until midnight?

CR: Um, what I would do is when I got on the “L” going back home—which was way north, almost to Evanston, so it was like a half-hour ride—I would sit there and go over and over in my head the story about what I would tell her, why I was where I was.

EM: What kinds of stories did you tell her?

CR: Oh, bowling with the kids from school, uh… That was, I used that a lot. I invented friends I was with…

EM: And she didn’t worry that you were out until midnight.

CR: She worried. And sometimes she would wait up for me. I was out to one or two and three in the morning sometimes. Oh, she would get mad and this and that. And she would threaten me with the police, you know, ’cuz I wasn’t supposed to be staying out that late. But she hadn’t really raised me. She was more of a caretaker at that point.

Anyway, so he was walking me back to the subway, and we got to the corner of Clark and Schiller. We’d just crossed the street. Uh, and I, I can’t remember if they were plainclothes or in uniform. I think they were in uniform. All of a sudden these two or three cops just appeared, what seemed to be out of nowhere. Uh, the first thing they asked me was how old I was. And I summoned up my deepest voice and said 17. Um, but they knew better—and also it was an area that I didn’t realize at the time where there was a lot of young teenage boy hustlers in the area.

Then they asked me who the other guy was, and I said, “He’s my uncle.” Uh, and then they took us into the police station. They had separated us at this point. I never saw him again until court.

EM: You must have been frightened by then.

CR: Yeah. But not, uh… I would say I was more angry than fr—it was a mixture of the two. I mean, ’cuz I knew what was happening was an assault on, on our freedom and my freedom and Frank Bucalo’s freedom.

Um, I’d heard of the Mattachine Society at this point. One guy I had met at the beach—what we called the beach, Oak Street Beach—his name was Harry, uh, Dilworth, was a member of Mattachine. I remember he had these Mattachine Reviews and ONE Magazines on his coffee table in his apartment. And, uh, I was just fascinated by them. Just idea that there was, uh, uh, gay men organizing. That’s the first I heard of it. I remember how excited I was when I first heard that, um…

EM: So they separated you.

CR: Right. Took us to the police station. I don’t know where—they must put him in a cell. I was never put in a cell—in a room. Anyway, the cop came in, it was a room with a table. I was sitting at the table and one of the cops came in. I remember he sat down and banged his fist on the table and said, “All right, you might as well tell me the truth right now. We’ve called your mother”—and I had a stepfather at that point, my mother had remarried—“and your stepfather and they’re on the way down here.” So I told him the truth.

EM: Why?

CR: I, I figured I had nothing to lose, you know, since my mother was coming down. First they were gonna find out that I was 14 and this guy wasn’t my uncle. And, uh, I’ve always believed in the power of the truth, figuring that if I tell the truth no harm can come.

EM: Your mother arrives.

CR: Right.

EM: She must not have—

CR: Speechless.

EM: She was not pleased.

CR: Not pleased, right. But she didn’t verbalize it. And I, I’m trying to remember—I think they told her that they’d arrested me for soliciting older men.

EM: Oh my.

CR: In other words, male prostitution. Uh, and my mother’s a very simple—she was born on a farm, you know, went through the Depression… To her, this was just…

EM: Shocking.

CR: She came down and got me. I don’t think she said a word. Uh, and then during the next, uh, two or three months, there was a series of, uh, hearings. And—

EM: What happened during the hearings? You had to go down to court?

CR: Yeah, she would drive me down there. And I’d have to take a day off from school and she’d have to take a day off from work. And she didn’t speak to me for two—a number of months, except for what absolutely had to be said.

EM: And this other man was in jail the entire time?

CR: Yeah. Yeah. I don’t think he was ever able to post bail. Uh, first it was a grand jury hearing. Uh, that’s the most vivid in my mind. The, uh, district attorney questioned me, and, again, I just told the truth, um—

EM: Did you feel then that you had done anything wrong?

CR: Of course not. Absolutely not.

EM: So was there ultimately a trial?

CR: Mm-hmm. There was a trial number of weeks, might have been a couple months later. And then there was other people I had to go talk to. I didn’t really know who they were. There were just people I had to tell—I had to repeat the, my story over and over and over again.

There was a hearing for me, juvenile hearing of some kind, and I remember I was sitting there with my mother when the hearing officer, judge, whatever—it was a woman—she sentenced me to, uh, uh, reformatory. And, uh, back then, you said “reformatory” to a kid, and it puts the fear of, you know, the Jesus into them.

So I remember when she sentenced me and my mother screamed, I remember, and begged. I’d never heard my mother—she’s a rather outwardly unemotional kind of person—begged this woman, she would do anything if they wouldn’t send me away. And, uh, they didn’t. I was put on probation for two years and had to report to a probation officer.

EM: What were you guilty of?

CR: Uh, juvenile delinquency, I guess, was the… They still believed I was a teenage prostitute, boy prostitute. I remember the DA, during Bucalo’s trial, getting me out in the corridor like this up against the wall…

EM: He was holding you by your collar.

CR: Yeah, like this, up against the wall, just furious with me. Wanted me to testify the guy had paid me money, and it wasn’t true. I mean, I didn’t, I didn’t even know what prostitution was. I literally didn’t know what prostitution was. But this DA just couldn’t believe this 14-year-old kid would go out cruising the streets, looking for men to go home and make love with. It was totally beyond his capability of understanding.

EM: So you were sentenced to two years probation.

CR: And my mother had to send me to the fucking psychiatrist.

EM: How often did you go?

CR: Oh, I think it was once a week or something like that. He was this nice little guy, and I remember the first time we went up there, uh, he told me about Ancient Greece, where homosexuality was normal or something. And then—again, looking back on it, um, he was obviously very hep and very wise and, and knew what was going on, whereas the cops didn’t.

I’d invented girlfriends and stuff at that point for the probation officer. Those—I did tell lies to him. Uh, and my mother would, we had social center dances in, uh, high school, on Friday nights in, in the gym. And she would drive me over there to the gym, watch me go up into the—there were these big doors heading into the gym—and I’d watch for her to drive away and I’d go out and get the hell and go downtown. This is like two weeks after my arrest, you know?

EM: What were you looking for downtown?

CR: Guys. Just the, all kinds of guys.

EM: Uh-huh. Was it love? Was it just sex? Was it…?

CR: Oh, I—at, at that age, you have this, uh, fantasy of, of, of love, this fantasy of, uh, caring or something. There’s closeness more than anything that I wanted. I just knew that I loved men. I would prefer to have had affairs with guys in, in school. I always had crushes on other, you know, guys my own age in school, but there’s nothing I could do about that. I couldn’t ask them to dance or, you know, anything like that.

EM: Um, that experience must have had an impact on you and looking back on it now.

CR: Well, it made me an angry queer. Still am.

———

EM Narration: Because of Craig Rodwell’s age, and his mother pleading on his behalf, Craig got to go home. Frank Bucalo, who was arrested along with him, was not so lucky. As Craig recalled in various interviews, Bucalo was sentenced to three to five years in prison for committing a so-called “crime against nature.”

In a 1970 oral history conducted by Kay Lahusen and John Francis Hunter for the book, The Gay Crusaders, Craig was asked whether the experience had left him with a sense of guilt. He said it had, and that he’d often wanted to find Bucalo and, quote, “somehow make up for what the court did to him.”

Craig Rodwell died of stomach cancer on June 18, 1993. He was 52. He was survived by his mother. Craig’s store, the Oscar Wilde Bookshop, continued on for another 16 years.

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible, including producer Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Cathleen Conte, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Special thanks to our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you also to all the people who pitched in to help us try to learn more about Frank Bucalo’s fate. Unfortunately, we all came up empty-handed. And thanks to the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division for their assistance with photos and other images.

Season eleven of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation; Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS; the Calamus Foundation; Christopher Street Financial; Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson; Louis Bradbury; David Quirolo; Lee Schere; the Danser family; Andra and Irwin Press; and Greg Adgate, who made a donation in honor of his daughters Anna and Grace. Thanks, Greg!

Head to makinggayhistory.com where you’ll find all our previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature. It’s also where you’ll see never-before publicly seen photos from Craig Rodwell’s childhood.

If you’ve already subscribed to our brand new Patreon channel, this week you’ll have access to our very first post—a video of my recent conversation with Patrick Hinds, the podcast star and founder of the Obsessed Network, who is obsessed with Craig Rodwell. We talk about Craig’s place in LGBTQ history and I play Patrick some archival audio that pits Craig against Larry Kramer over Kramer’s controversial 1978 novel, Faggots.

If you’re not a patron yet, consider becoming one today so you don’t miss out on any exclusive content. For a monthly donation of $5, you’ll get previously unreleased bonus clips from my archive and new video interviews with some of the people we’ve featured, as well as other LGBTQ history makers. Find out more about joining Making Gay History’s Patreon community and sign up at patreon.com/makinggayhistory or go to makinggayhistory.com and click on the Patreon link in the home page banner.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

———

Note: An earlier version of the episode intro incorrectly referred to the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop as the first store of its kind in the world. In fact, per the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, it was “the first gay and lesbian bookstore to operate on the East Coast. It was preceded by Adonis Bookstore, in San Francisco, which opened several months earlier, in March 1967. However, after a couple of years, Adonis evolved into a gay adult bookstore, which made Oscar Wilde the first of its kind in the United States to operate long term.” With many thanks to the MGH listener who brought the error to our attention.

###