Dr. Evelyn Hooker

Dr. Evelyn Hooker in an undated photo. Courtesy of Frameline Distribution.

Dr. Evelyn Hooker in an undated photo. Courtesy of Frameline Distribution.Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: In 1945 Dr. Evelyn Hooker, a UCLA psychologist, and her husband sat down for a nightcap at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco with her former student Sam From and his male partner. Sam told Dr. Hooker that it was her responsibility to study “normal” homosexuals to show the world what they were really like—to challenge the commonly held belief that gay people were by nature mentally ill. Dr. Hooker took up the challenge soon after, but then life intervened, derailing her research until 1953, when she secured an unlikely government grant to pursue a study comparing 30 straight men to 30 gay men.

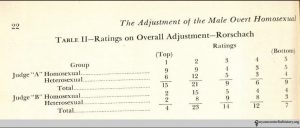

Three years later Dr. Hooker presented the results of her study, “The Adjustment of the Male Overt Homosexual,” at the 1956 American Psychological Association (APA) convention in Chicago (the study was published in 1957). She rocked the profession by demonstrating that gay men were just as sane as straight men. While it would be another 17 years before the American Psychiatric Association would remove homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual’s list of mental illnesses, it was Dr. Hooker’s study that paved the way, legitimizing homosexuality as a respectable field of study.

There’s so much more to this story and the study. And fortunately there are many resources, a sampling of which you’ll find below.

———

Dr. Katharine S. Milar, a professor of psychology at Earlham College, offered a concise overview of Dr. Hooker’s life and work for the American Psychological Association’s website, including details about how she conducted her landmark study (which was derisively referred to as “The Fairy Project” by some federal officials).

For a broad overview of Dr. Evelyn Hooker’s life, including a biographical sketch that was adapted from an article in the American Psychologist, as well as tributes and obituaries, have a look here.

The American Psychological Association provides a summary of Dr. Hooker’s groundbreaking study—“The Adjustment of the Male Overt Homosexual”—here. A copy of Dr. Hooker’s paper is available here.

In 1991, Dr. Hooker was given the APA’s Award for Distinguished Contributions to Psychology in the Public Interest. And in 1992 the documentary Changing Our Minds: The Story of Dr. Evelyn Hooker was released. You can watch a clip from it here.

You can find Dr. Hooker’s oral history in Eric Marcus’s book Making Gay History.

Beginning in 2008, the APA’s “Division 44” (Society for the Psychological Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues) named an annual award in Dr. Hooker’s honor: Evelyn Hooker Award for Distinguished Contribution by an Ally.

Here is an overview of the American Psychological Association’s current work concerning LGBTQ rights. Dr. Hooker’s work is cited in the opening sentence.

This American Life produced an episode in 2002 featuring a surprisingly personal story hosted by Alix Spiegel about her psychiatrist grandfather and the 1973 removal of homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of mental illnesses. The piece includes recorded interviews with some of the key players in that drama, including Dr. Charles Socarides and Dr. John Fryer (aka, Dr. H. Anonymous). It’s a must-listen episode that helps explain how millions of homosexuals gained an instant cure. Dr. Hooker’s landmark study is cited and gay rights champion Barbara Gittings is referenced as well (although she’s misidentified as a librarian—she loved books and was deeply involved with the American Library Association, but wasn’t a librarian).

The Kinsey Institute at Indiana University offers a treasure trove of information and research on human sexuality and gender.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

This week you’ll meet Dr. Evelyn Hooker. She was something else. A force of nature. Even at 81. But you had to be a force of nature to do what she did when she did it.

Back in 1953 Dr. Hooker started work on a first-of-its kind psychological study that demonstrated gay men were no different from straight men when it came to their sanity.

At that time, just about everyone thought gay people were mentally ill. Homosexuality was a sickness. Even most gay people believed it.

And what do you do when you’re sick? You try to get cured. And that’s what a lot of gay people did. They spent years and fortunes trying to get over an illness they didn’t even have.

The really unlucky ones were forced against their will into horrible treatments that were nothing short of torture. Lobotomy, chemical castration, and shock treatment. And I’m really not kidding. Those were the ways in which gay people were treated.

This is a story about serendipity—a pivotal moment in history when a gay psychology student named Sam From set his sights on Dr. Evelyn Hooker. He urged Dr. Hooker to study normal gay people to show the world what they were really like. That was in 1945. And then life got in the way and Dr. Hooker set aside Sam’s project. You can read about this part of Dr. Hooker’s life on our website, makinggayhistory.com.

So now it’s 1953 when Dr. Hooker gets back to work.

She found the men she needed, she gave them psychological tests and then got top psychologists to review the results. When you hear Dr. Hooker talk about someone named Bruno, that’s Dr. Bruno Klopfer, a German psychologist. He was one of the study’s judges.

So in August 1989 I fly out to Los Angeles and drive my rented convertible, because it’s Los Angeles, to Dr. Hooker’s apartment in Santa Monica. It’s just a couple of blocks from the beach. She welcomes me into her double-height living room. Book shelves reach to the ceiling. And I just about choke on the air. It’s saturated with smoke and nicotine. And I’m thinking, please god, don’t smoke through the whole interview. She does.

Before we sit down, Dr. Hooker shows me her small office. It’s lined with cabinets filled with the files of the 60 men she studied. The contents of those cabinets changed the course of history.

We head back into the living room. Dr. Hooker leads the way. She walks slowly and deliberately. She’s got spinal arthritis and gingerly lowers her six-foot frame into her high-backed leather easy chair. I clip the microphone to her blouse. She lights a cigarette and draws deeply. And I press record.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Dr. Evelyn Hooker. Sunday, August 20, 1989. Interviewer is Eric Marcus, location is the home of Dr. Hooker in Los Angeles, California.

Dr. Evelyn Hooker: They wanted us to come to dinner. We went to dinner. His lover was introduced as his cousin, a much older man, George. And, you wouldn’t believe, since you didn’t live then… You would not believe how gay men, they could put on a business suit… no humor, they were afraid to have me know that they… they wanted my approval so much that they were afraid to let me know that they were gay. Anyway, delicious dinner, and gradually they became very good friends.

EM: He still hadn’t told you that he was…

EH: I don’t even know… Oh, yes, gradually the fog came down because they saw that I didn’t care what they were like. I liked them. I found them to be very interesting people. I came to be very fond of them. And I don’t even remember a time when… I’m sure it wasn’t a time when somebody said, “Look, we’re gay, now you…” There was nothing like that. It was just a very gradual letting down of hair.

After I’d known them about, I would say, about a year, we were invited by Sam and George to go with them on a holiday, on Thanksgiving holiday to San Francisco. We get to San Francisco and the first night or second night we’re there, Sammy insists that we should go to Finocchio’s. My eyes were wide. I’d never seen anything like that.

EM: What was Finocchio’s like then?

EH: Oh, my god. Well, are they still there, the two old bags from Oakland?

EM: I don’t know. But for people who won’t know what it is, can you just describe what the place was like?

EH: Well, it was of course a tourist place. It was not a gay bar. Yes, to be sure, they served drinks. But it was essentially a tourist place for primarily, as I saw it at least, for transvestites, or would-be transvestites, or transsexuals. And of course it was altogether a different kind of world. They had a lot of patter, female patter they call it, and it was funny. I’m sure they’re dead by now and that’s a shame. They were great. I thought they were great.

EM: So you went back to the Fairmont…

EH: We went back to the Fairmont. We sat down, we were gonna have a snack before we went to bed. “Now,” he said, “we have let you see us as we are and it is now your scientific duty to make a study of people like us.” Imagine that! And by people like us he meant, “We don’t need psychiatrists, we don’t need psychologists, we’re not insane, we’re not any of those things they say we are.” I said, “But I couldn’t study you because you’re my friends. And I couldn’t be objective about you.” And to which he replied, “Hmm, we can get you a hundred men, any number of men you want. You’re the person to do it! You know us! And you have the training.”

EM: Why would he want you to do a study? What was the purpose of doing a study about these…?

EH: The purpose of doing a study was to show the world what we’re really like. I could understand there was excitement about doing something that you felt was going to be groundbreaking, whatever happened. Because it would have been the first time anybody ever looked at this behavior and said, “Now, we’ll use scientific tests to determine is this pathological or not?”

EM: All this time everyone had said it was pathological without any studies.

EH: Without any studies. They represented, even in that relatively small group, they represented a cross section of personality, of talent, of background, of adjustment, of mental health, the whole kit and caboodle was there.

EM: So even by then you knew that the current thinking was incorrect.

EH: But I had to prove it.

EM: Dr. Evelyn Hooker, tape two, side one.

EH: I had just heard that the National Institute of Mental Health had just been founded. And I said to myself, gee, well, I think what I’ll do is to apply to the National Institute of Mental Health. If they think this project is worth doing, if the study section thinks this is worth doing, then I’ll do it.

The chief of the grants division flew out and spent the day with me. He wanted to see what type of kook this was. Is she really crazy or can she do this? At the end of the day, he said, “I’ll tell you we’re prepared to make you this grant.”

I decided with the consultation with my statistical consultant, Dr. Gingerelli, that we would settle for a small group, 30 in each group, 30 heterosexuals, 30 homosexuals. But the problem was getting the straight people, the straight men.

EM: Why?

EH: Well, again, remember, this is the early ’50s. And I thought that if I went to, let’s say, to labor unions and asked the personnel director and told him what I was doing that he would be willing to speak individually to men who he thought were thoroughgoing heterosexual men. Not a bit of it. He wouldn’t do it.

I was just at my wits’ end to find people who were of the general educational, economic, etc., level of my gay group. And one day I was sitting in the study and I heard some steps coming down the driveway and I looked out and there were blue trousers legs. Four of them. And I said, “Oh boy!” And, so it turns out that they were firemen and they were from our local fire department and they were looking at our fire precautions. So I walked over to talk to them. One of them said, “Oh, you’re a writer.” I said, “Well, no, not exactly. I’m a psychologist.” “Oh,” he said, “I have two boys and they’re in a psychology experiment at UCLA.” And I said, “Oh, would you be willing to be in a psychology experiment?” “Oh, no, I couldn’t do that,” he said. I said, “Well, wait a minute, what about on your days off?” And then he said, “Well, then I have to take care of my boys.” I said, “What if I pay the babysitter?” Finally, he broke down and said, “Okay.”

He introduced me to a cop. And did I learn about the ins and outs of the police department downtown! And he wanted to come to me because it turns out he was having marital trouble and he hoped that he could exchange a little information for…

EM: A bargain.

EH: I tell you there’s nothing more interesting than human beings. Anyway, so we all end up… the whole thing ends up by having the 30/30.

At that time, the ’50s, every clinical psychologist worth his salt would tell you that if he gave those projective techniques that he could tell whether a person was gay or not. No such thing. I showed they couldn’t.

When Bruno did the judging, people said, “You’ll never get away with this. Your face will reveal it. He’ll know.” I said, “Oh, nonsense.” Uh, anyway, and he’s the great Rorschach expert, and every day, I think we spent ten days just going over one after the other and one after the other. But that was of course terribly exciting to see Bruno, who said, “You must let me know where I made the errors afterwards.” And he would say, “Oh, I knew, I knew there was something about that. I knew there was something about that.” But terribly exciting days. Terribly exciting days.

See, I presented that paper at a meeting of the American Psychological Association in Chicago.

EM: Uh… “The Adjustment of the Male Overt Homosexual.”

EH: Right. Right. The air was electric. It was just electric. And of course there were people, some, not too many, but there were some people who were saying, “Well, of course that can’t be right.” And they set off to try to prove that I was crazy. The hard-liners among the psychoanalysts, like Irving Bieber, for instance, they would as soon shoot me as look at me.

EM: Why was it so electric?

EH: Well, if you’re challenging a long and commonly held position and there are—and you know that there are thousands of lives at stake, I think everybody who, unless they were severely prejudiced, as lots of people are, you know, that in general it was a very exciting, very exciting concept.

EM: What was the impact of your study then, ultimately?

EH: That I had made it a respectable field of study. It started a whole spate of pieces of research by gay and straight psychologists alike who had the courage to do it after I had done it and who came up with bits and pieces of this formulation.

What means most to me, I think, is… um, excuse me while I cry… If I went to a gathering of some kind, gay gathering of some kind, I was sure to have at least one person come up to me and say, “I’ve wanted to meet you because I wanted to tell you what you saved me from.” I’m thinking of a woman, a young woman, who came up to me in a meeting and said that her parents put, when they discovered that she was a lesbian, put her in a psychiatric hospital and that the standard procedure in that hospital was electroshock, but that her psychiatrist was familiar with my work and he was able to keep them from giving it to her, with tears streaming down her face.

I know that… well… I know that wherever I go, whether I know it or not, that there are both men and women for whom my little bit of work, and my caring enough to do it, has made an enormous difference in their lives. So I feel that that’s my monument.

EM: That’s a hell of a monument.

EH: Yes, it is.

———

EM Narration: When Dr. Hooker got back from the Chicago convention she met up with a group of the gay men she interviewed for her study at an L.A. restaurant and she shared the results with them.

But one person who never knew the results was Sam From, Dr. Hooker’s friend. He’s the one who urged her to pursue the study in the first place. He was killed in a car crash before the study was finished.

The last time I talked with Dr. Hooker was in 1992. By then she had circulatory problems and she couldn’t travel. So she missed the premiere of the documentary about her life at the Castro Theater. That’s in the heart of San Francisco’s gay community.

But I was there and as soon as I got home I called Dr. Hooker with a full report about the audience’s reaction. They gave it a standing ovation. “That was for you,” I told her. I can’t remember what she said, but I’ll never forget the emotion in her voice. She was so thrilled and delighted. I wish she could have been there.

———

I’d like to thank our executive producer, Sara Burningham; our audio engineer, Casey Holford; and our talented composer, Fritz Myers. Thank you also to Hannah Moch, our social media guru; our webmaster, Jonathan Dozier-Ezell; and our head of research, Zachary Seltzer. We had production assistance from Jenna Weiss-Berman, whose commitment to this project made it possible.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division. Funding is provided by the Arcus Foundation, which is dedicated to the idea that people can live in harmony with one another and the natural world. Learn more about Arcus and its partners at arcusfoundation.org.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to the Making Gay History podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also find all our podcasts on our website at makinggayhistory.com. That’s where you’ll also find photos and really interesting background information on each of the people we feature.

So long! Until next time!

###