Stonewall 50 – Episode 3 – “Say It Loud! Gay & Proud!”

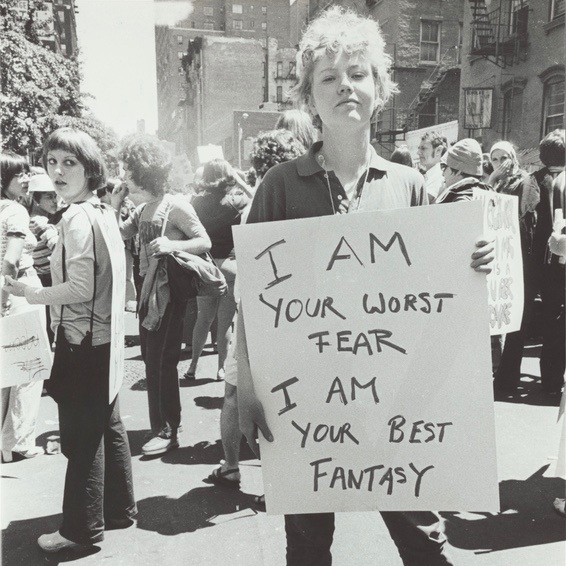

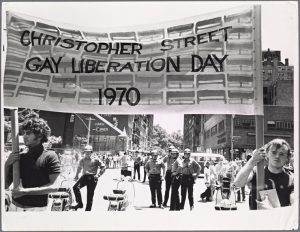

Donna Gottschalk—lesbian, feminist, activist, photographer, artist—at the first Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day march in New York City, June 28, 1970. Credit: Photo by Diana Davies, courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Donna Gottschalk—lesbian, feminist, activist, photographer, artist—at the first Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day march in New York City, June 28, 1970. Credit: Photo by Diana Davies, courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: After listening to Making Gay History’s first two Stonewall 50 episodes, you know that Stonewall isn’t where it all began. By the time of the June 1969 Stonewall uprising, the homophile movement was nearly two decades old and there were between 50 to 60 organizations across the country.

But Stonewall was definitely the start of something—and something big, because one year later, when LGBTQ people gathered at Sheridan Square to mark the uprising’s first anniversary and the start of the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, there were 1,500 organizations. And pre-Stonewall activists, who numbered in the hundreds, were joined by thousands—even tens of thousands—of newly energized activists committed to fighting for gay liberation.

This new gay liberation phase of the movement didn’t just happen. The Stonewall uprising was followed by a year of intensive organizing. Even before the six nights of confrontations outside the Stonewall Inn had come to an end, meetings were called by movement leaders to channel the anger and energy released by the multi-day melee on the streets of Greenwich Village. Veteran homophile activists joined with LGBTQ folks who had earned their stripes in the Black civil rights movement, the anti-war effort, and the women’s movement to launch new in-your-face organizations dedicated to confronting the system—the discrimination, harassment, and criminalization—that forced gay people to live in fear.

Instead of asking to be accepted, activists now shouted their demands on the streets: “What do we want? Gay rights! When do we want them? Now!” And in the aftermath of a police raid where “fems, nances, fags, and queens” chased the police, instead of the other way around, activists fully embraced their new power, chanting, “Say it loud! Gay and proud!”

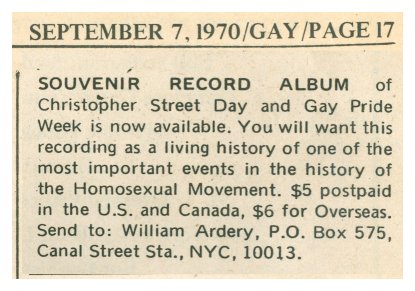

In this third Stonewall 50 episode, we take you back to that transformational year through the voices of just some of the people who lived it and led it. We had a special guide to help us on that journey: Breck Ardery, a pioneering young journalist who made the very first audio documentary about the Stonewall uprising and its aftermath. And who recorded in real time New York City’s very first Christopher Street Liberation Day March on June 28, 1970.

Have a listen.

———

Linda Hirshman, author of Victory: The Triumphant Gay Revolution, puts Stonewall into perspective in this 2019 Los Angeles Times column.

The episode touches on how the media reported on the Stonewall uprising at the time. For a sampling of how the riots were covered, explore the links below:

- New York Mattachine Newsletter (written by Dick Leitsch)

- New York Daily News

- Village Voice

- New York Times: June 29, 1969; June 30, 1969; July 3, 1969

This article from the History Channel looks at how the first Christopher Street Liberation Day March in New York City was organized and how the first anniversary of Stonewall was marked with marches in Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. And this Washington Blade article offers detail on how that first march came about through Craig Rodwell’s original proposal.

In this 2010 Village Voice piece, Fred Sargeant, one of the principal march organizers along with his partner, Craig Rodwell, Ellen Broidy, and Linda Rhodes, wrote about that first New York march and how it came to be. Ellen Broidy offers her perspective in this 2018 interview from the National Park Service’s Stonewall Oral History Project.

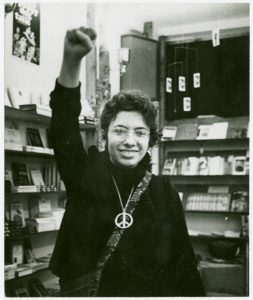

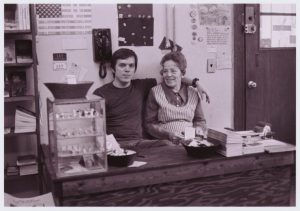

Learn more about Craig Rodwell in this biographical overview and watch him in conversation with Vito Russo at the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in this 1983 interview from Russo’s TV show Our Time, starting at 3:30.

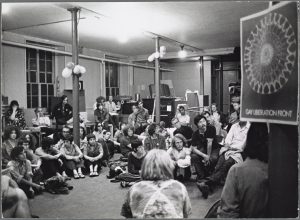

In this 1994 interview, Martha Shelley discusses her involvement with the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). For more information about GLF, check out this page on the New York Public Library’s website.

To explore archival issues of Come Out!, the GLF’s newspaper, go here. Read about GLF cofounder Bob Kohler in his Village Voice obituary here. And visit the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project website for more information about Alternate U, the GLF’s home base.

For an overview and history of the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), have a look at this article by Linda Rapp from the GLBTQ Archive. Read the New York Times obituary of GAA cofounder Marty Robinson here.

As this HuffPo article and video show, Sylvia Rivera continued to stand up for homeless trans youth until the end of her life. Her memory lives on with the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, an organization that “works to guarantee that all people are free to self-determine their gender identity and expression.”

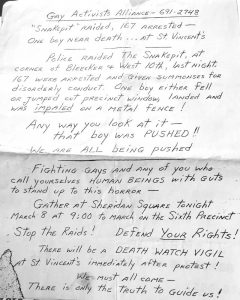

For information about the March 8, 1970, Snake Pit raid—which radicalized post-Stonewall activists Morty Manford and Vito Russo—go here.

Watch Gay and Proud, a 12-minute documentary by lesbian activist Lilli Vincenz about the first Christopher Street Liberation Day March in New York City on June 28, 1970.

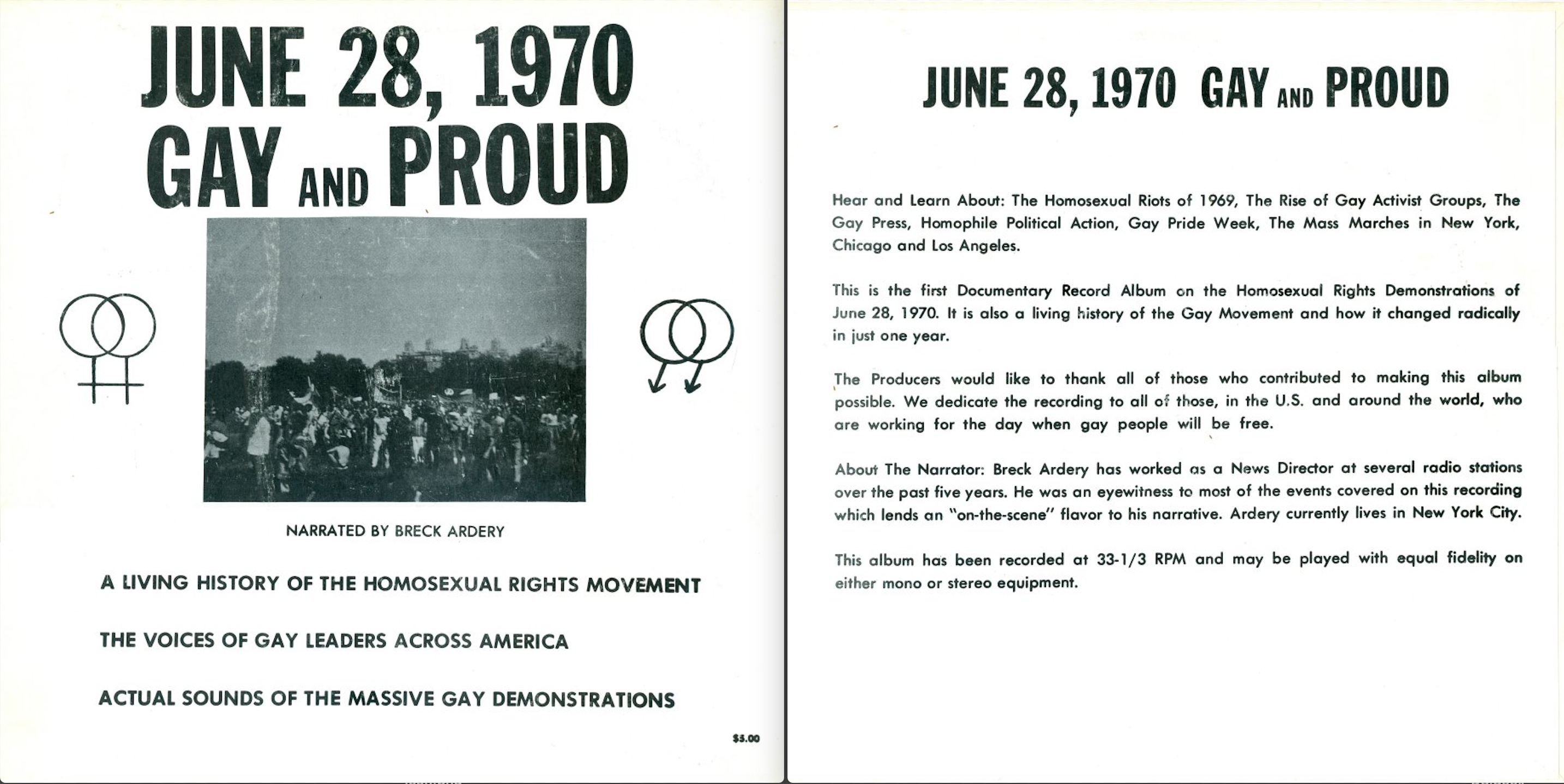

To listen to Breck Ardery’s pioneering record June 29, 1970: Gay and Proud in its entirety, go here.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus: Do you think all of this was in part because people were so angry for so long?

Sylvia Rivera: People were very angry for so long. I mean, how long can you live in the closet?

———

EM Narration: It’s the beginning of July 1969 and the riots are over. But some of the most important things about the Stonewall uprising have yet to happen. I want to take you through the year or so of chaos, organizing, protest, and celebration that happened after Stonewall. To hear how activists took six nights of unrest in Greenwich Village and built them into a national movement. And we’re going to try to trace how the anger that erupted outside the Stonewall Inn was channeled, co-opted, and in some cases excluded from organizations and events that helped shape the movement for decades to come.

How anger fueled power and joy coalesced into pride.

I’m Eric Marcus. This is Making Gay History’s Stonewall 50 season, and I’m joined by an amazing guide to help us on this part of our journey.

———

Breck Ardery: This is Breck Ardery, and I am the producer and narrator of a documentary record album called June 28, 1970: Gay and Proud.

———

BA: The Stonewall rebellion served notice on the heterosexual majority that a growing number of gays were not afraid anymore and were not content to continue living out their lives in fear and oppression.

———

EM Narration: Breck Ardery made the first ever documentary about Stonewall and its aftermath in 1970. He made it in his spare time, with a Sony tape recorder, and he released it as a vinyl record, pressing just 400 or so copies.

———

BA: The Stonewall rebellion will be remembered as one of the major turning points in the homosexual struggle for equality.

———

EM Narration: When I held this record and played it for the first time just a couple of months ago, it gave me chills. The album cover reads, “June 28, 1970: Gay and Proud—A Living History of the Homosexual Rights Movement.” Put it on a turntable, drop the needle, and you’ll hear the sound of a revolution. An audio documentary made by a gay person about the year that gay liberation found its voice.

———

Chanting Crowd: Say it loud, gay and proud! Say it loud, gay and proud!

Radio Announcer: June 28, 1970. One of the most important days in the history of the American homosexual’s fight for freedom. Thousands marched in New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles. They represented the mood of growing militancy in the United States gay community.

———

EM Narration: That powerful revolutionary voice emerged directly from the riots. Before Breck Ardery started working on his documentary in the spring of 1970, activists old and new, galvanized by the Stonewall uprising, were organizing at an unprecedented pace and intensity. Later, we’ll bring you more from Breck and his documentary record to tell the story behind the historic marches one year after the riots.

But first we’re going to take you back to those first days, weeks, and months of activism after the shit hit the fan.

The Stonewall riots had made news, but the coverage in the mainstream press was full of the usual homophobia and bigotry.

———

Actor 1: New York Times, June 28, 1969. “Four Policemen Hurt in Village Raid.”

Actor 2: “Hundreds of young men went on a rampage in Greenwich Village shortly after 3:00 a.m. yesterday after a force of plainclothes men raided a bar that the police said was well-known for its homosexual clientele.”

Actor 1: New York Daily News, July 6, 1969. “Homo Nest Raided. Queen Bees Stinging Mad.”

Actor 2: “Last weekend the queens had turned commandos and stood bra strap to bra strap against an invasion of the Tactical Police Force.”

Actor 1: “With a battle cry of ‘gay power,’ the Nellies, fems, gay boys, queens—all those who flaunt their homosexuality—have been demonstrating that they have indeed been pushed too far.”

———

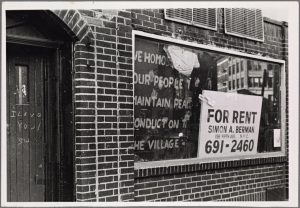

EM Narration: Before the riots ended, the Village Voice published its account of what happened. The Voice was a downtown alternative weekly newspaper, but it was not progressive on gay issues. In fact, the Village Voice’s reporting on the riots was particularly barbed.

———

Actor 1: “The sudden specter of ‘gay power’ raised its brazen head and spat out a fairytale the likes of which the area has never seen. The forces of faggotry, spurred by a Friday night raid on the Stonewall Inn, rallied Saturday night in an unprecedented protest.”

———

EM Narration: On the first night of the riots, one of the Voice’s reporters was on the street. The other was inside the Stonewall, barricaded in with the cops. The account they wrote was published in the middle of the week of riots.

———

Actor 2: “Full Moon over the Stonewall.” “The sound filtering in doesn’t suggest dancing faggots anymore. It sounds like a powerful rage bent on vendetta.”

———

EM Narration: The article provoked an angry reaction immediately. Hundreds of young people massed outside the Voice’s offices, which just happened to be a couple of doors down the street from the Stonewall Inn. Gay youth were joined by members of radical groups like the Black Panthers and the anti-war Yippies.

Despite the violent protests, Village Voice writers kept up the anti-gay language.

———

Unidentified Speaker: Um, and then the next week the Voice was filled with letters saying how the use of the word “faggot” was antithemia [sic] to everything the Voice stands for and to everything I stand for, blah blah blah. There was an amazingly obnoxious article by, I can’t even… Henry Troy Spencer or something, I don’t know. [Crosstalk.] Walter Troy Spencer. Some amazing three name, you know… He comes out and says, “the great faggot revolution, the faggotry, and the purple finery,” you know… Whew.

———

EM Narration: Activists like the one you just heard speaking in a recording from 1969 would soon have an answer to the Voice’s bigotry with more organizations, more protests, and their own newspapers with titles like Come Out!, GAY, and the Queen’s Quarterly. The days of gay people tolerating hateful press coverage were over.

———

Unidentified Speaker: If Mattachine wants to act straight, they’re going to act straight into irrelevancy.

———

EM Narration: At the end of June and in early July 1969, members of the newly formed Mattachine Action Committee were in the streets, handing out flyers for a meeting scheduled for July 9. But there was some homophile business to attend to in Philadelphia first. The last of the annual Reminder Day protests on July 4 at Independence Hall.

In episode one, you heard how the rift between one generation of activists and the next was breaking out into the open. While Craig Rodwell was calling Frank Kameny “Auntie Tom” and young activists were defiantly holding hands, Morty Manford, fresh from witnessing the Stonewall riots, was struggling with his identity when he headed to Philadelphia that Friday.

———

Morty Manford: Where did I go? I went with a friend from New York from the Stonewall. I think I wore sunglasses.

EM: To hide your identity?

MM: Yes, and then when I saw cameras I think I turned my face away. It was a process of starting to deal with it a little bit at a time.

———

EM Narration: Morty Manford was still processing. He hadn’t come into his own as an activist yet, but Martha Shelley was ramping up. Before the riots, she’d been the president of the lesbian homophile organization the Daughters of Bilitis, and she went to the July 4 Reminder Day protest, too, dutifully decked out—awkwardly—in a skirt and blouse. But Martha was mulling the idea of something more militant than a picket. She and the other members of the Mattachine Action Committee wanted a march. And they got one. On Sunday, July 27, 1969, just a month after the riots, hundreds of people gathered in Greenwich Village to demand an end to discrimination and police harassment. It was the biggest gay rights march to date.

———

Martha Shelley: So we marched around the Village and we ended up at Sheridan Square across the street from the Stonewall Inn.

EM: How many were there of you?

MS: I thought there were only 500, some people said that there was more. I have heard it as much as 2,000. And I remember us jumping up on this little water fountain and making our speeches, and then afterwards I said, “Well, we should disperse and go home because there’s gonna be more, keep your ears open. There’ll be more meetings, and this ain’t the end of us.”

———

EM Narration: She was right. It wasn’t the end of them.

———

Charles Pitts: Tonight our program deals with the radical homosexual organizations. The Gay Liberation Front is the name for a radical militant homosexual organization which formed soon after the Stonewall riots.

———

EM Narration: This is New York community station WBAI’s radio show for and about the gay community, called The New Symposium.

———

Unidentified Speaker: Michael Brown could tell us… How did GLF begin?

———

EM Narration: Hosts Charles Pitts and Pete Wilson taped this broadcast in an apartment with a group of GLF members in early September 1969.

———

Michael Brown: It grew out of Mattachine Action Committee shortly after the Stonewall riots, and there were a number of people who felt that there was a need for an organization which was more, in closer time with the community than Mattachine. And it was a division of feeling with the Mattachine Society, and we left and then…

———

MS: Marty Robinson thinks I came up with the name Gay Liberation Front. I don’t know who said it. I remember it coming up at the meeting and I remember pounding my fist on the table, yelling in exultation, “That’s it, that’s it, we’re the Gay Liberation Front!”

EM: Why? What was it about that name that did it for you?

MS: Because it was like the National Liberation Front of North Vietnam.

EM: What was that?

MS: That was the Vietcong. The army of liberation that was heroic in the eyes of the Left. Here were all of these Vietnamese peasants daring to stand up to the most powerful army in the world with all of its tanks and helicopters and napalm. We pinned all of our fantasies on that group without understanding anything about their culture. The one thing we did get right is that they were fighting against a very oppressive force that was trying to deny them the right to run their own country their way. And it was David against Goliath.

———

EM Narration: Martha Shelley was one of the co-founders of the GLF, although “founder” is a tricky word to attach to the Gay Liberation Front, which was a strictly non-hierarchical and consensus-led group. GLF members were often active in other movements fighting for racial justice, socialist causes, and women’s liberation.

———

Unidentified Speaker: Like, what I learned at women’s lib yesterday at that demonstration where I’ve been feeling my own [inaudible], the more I affirm myself, you know, the more I am myself in the world, and the more we, like, relate to each other and do our thing, the more we’re going to be able to do what’s natural to us and feel good about it and let the weight of the hang-up fall on those who are distressed. Like, I can look at a woman now and say, “I’m homosexual,” you know, and smile and feel good about it and watch her whole thing, like, collapse and, you know, go crazy. Right, you know. And I don’t have… In all my life I’ve borne the weight of others’ hang-ups. I’ve internalized it myself. I don’t have to do that.

———

EM Narration: We’re not sure which GLF member that was speaking in September 1969, but we do know that over the summer of 1969, the newly formed GLF had got together with the Alternate U and found a home.

The Alternate University or AU was a group and it was a place—a buzzing center of counterculture and political organizing in a big industrial loft on the corner of 6th Avenue and 14th Street at the edge of the Village.

Martha Shelley could still picture it vividly when I asked her about it 20 years later in 1989.

———

MS: Some of the graffiti on the wall, “And God said E=MC2 and there was a light show—groovy.” That kind of graffiti.

EM: Ancient language.

MS: Yeah. And we had dances there and they were massive. I mean, these dances were jammed.

EM: Dozens of people, hundreds of people?

MS: Hundreds. I remember serving on security one night and being up most of the night because we’d had threats. The Maf—, I think the Mafia didn’t… The Mafia never really did anything, but there were people who didn’t like us having dances where we sold beers for 50 cents and sodas for a quarter when they were busy flogging beers for a couple of bucks in their damn bars. And you could dance all night, you didn’t have to pay extra to go into a special room where dancing was allowed, which is the way it was at some of the old bars, like The Sea Colony.

I think the dances were really important because we were expressing ourselves physically, we were expressing our affection for each other and our sense of community in those dances, which you couldn’t do in gay bars. Also, there was this tremendous emphasis in the gay bars on looks, and I’m sure there still is. But at least in the gay liberation dances there was this consciousness of, We are here to give each other love and acceptance, and who we are is okay. And there were circle dances. You never saw that in a gay bar. Instead of two people against the world it was our whole community.

———

EM Narration: A few minutes’ walk from Alternate U at Craig Rodwell’s apartment at 350 Bleecker street, plans were afoot for more marches.

———

Craig Rodwell: We sat here—Ellen, Linda, Fred, and myself. This was before the ERCHO conference.

———

EM Narration: A quick translation: Fred was Fred Sargeant, Craig’s lover. Ellen Broidy and Linda Rhodes were lesbian student activists and they were a couple, too. ERCHO was—and are you ready for a sexy name?—the Eastern Regional Council of Homophile Organizations, which was behind the Reminder Day pickets.

———

CR: And we did up a formal resolution, everything, to change the annual Reminders to Christopher Street Liberation Day to be celebrated the last Sunday of June to commemorate the birth of the gay liberation movement as exemplified by the Stonewall riots. We sat here for hours and worked the whole thing up with resolutions and… And we presented to ERCHO in November of ’69.

———

EM Narration: It was Ellen Broidy who stood up at the ERCHO conference in Philadelphia in November, and proposed the resolution for a new annual march. Ellen says she wanted to take the fight for gay rights to the next level.

———

Ellen Broidy: I never would have stood up in Philadelphia at the Eastern Regional Conference and said get rid of this march around Independence Hall if I had thought it was anything other than a very conservative plea for acceptance. And I had no patience with that. We wanted to smash the state.

———

EM Narration: The motion to establish the march was passed by everyone except Dick Leitsch’s Mattachine. Martha Shelley had a theory about why some of the old guard were not big fans of the new radicalism.

———

MS: People would send in their money to DOB and Mattachine and hope that one person would be the leader and go out there and represent them while they hid in the closet and somebody else would fight for their rights. But once we were all out on the streets fighting for our rights, we wouldn’t need Dick Leitsch anymore or me or anybody else who was the public spokesperson.

EM: You didn’t really care, though, about your position. You didn’t want to be president.

MS: No. No. I just wanted to make the world safe for me, that’s it. So that I could live in my little, as it turned out, house without a white picket fence and enjoy my life and not feel that, you know, I was going to get thrown in jail for sleeping with a woman. I mean, I would have also liked to overturn the world, bring peace, justice, and prosperity to every human being on the planet. And I think that is still a fine idea, but I didn’t have any desire to run the world or be boss, and I still don’t.

———

EM Narration: Without the support of the Mattachine Society, and in fact not affiliated with any specific group, the newly formed Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee held its first meeting in January of 1970.

———

CR: Actually, the first meeting of the committee, it was like two-thirds women. And, actually, the first few meetings, the concept of the thing changed at every meeting because, like, the people, the meetings were different every meeting, and each group had a different idea of what it should be and how it should be set up. And finally we settled on the format that took place. And the idea, in a nutshell, is to set aside the day for a show of unity, solidarity, and pride, collective pride of gay people, and not to have it appear that it’s run or actually be run by one organization.

———

EM Narration: And the number of organizations was multiplying. In late December of 1969, activists frustrated with the GLF’s non-structure and its alliances with other, not explicitly gay causes, split off to form the Gay Activists Alliance—a single issue-group that counted Marty Robinson among its early members.

———

Marty Robinson: GAA is utilizing non-violent militancy to secure what it wants somewhat by hitting the system below the belt rather than just trying to cut the rug out from under the system entirely.

———

EM Narration: Sylvia Rivera was also an early member of GAA. This is the first ever recorded interview with Sylvia, taped in December 1970. Sylvia’s talking about how she joined GAA in February or March of that year, and about how she faced discrimination from the get-go.

———

Sylvia Rivera: I made a phone call from Jersey and said, “Do you accept transvestites?” At that time, I was still using the word “drag queen,” I said, “Do you accept drag queens?” “Sure, come on down.” So my friends and I tripped down there to the meeting from Jersey and we took a peek and it was nothing but butch male homosexuals that always oppressed transvestites. And we were very flamboyant with the makeup and everything, you know, tripping in, you know, really looking… beautiful.

So we walked in, and I come… “What’s your name?” At the table, you had to write your name. I said, “My name is Sylvia.” He says, “What is your name?” I said, “I’m Sylvia!” He says, “Well, we can’t accept that name.” So I wrote down “Sylvia Lee Rivera,” but in parentheses I have the habit of putting “Ray Rivera,” my real name. Even butch-identified, even men, you know, homosexual males that are dealing with their sexism, are always discriminating against transvestites because they just can’t, we’re threatening their masculinity. That’s the way they feel.

———

EM Narration: Within a month of joining GAA, Sylvia was arrested for petitioning for gay rights in Times Square. The cops said she was soliciting for sex. Sylvia had been harassed by the police and arrested scores of times in Times Square. This was the first time she had been arrested for exercising her civil right to protest.

———

BA: Of course conditions for gay people have not changed much for the better in the past year. And police raids, such as the one that triggered the Stonewall uprising, have continued, most notably at the Snake Pit, another Village bar. Bob Kohler of New York’s Gay Liberation Front says he thinks a repetition of the Stonewall riots is possible.

Bob Kohler: Yeah, yeah, I think it could happen again. I mean, the people, Stonewall was a dope drop. I mean, I think, people making a… Stonewall has become sort of a legend and the kids have become folk heroes, which really isn’t true, but something like the Snake Pit, you’ve got… They’re tinderboxes and I think, yeah, it could happen again. I would hope not, but I think it could.

———

EM Narration: It’s not like the police raids magically came to an end after the Stonewall riots. They continued. In the pre-dawn hours of March 8, 1970, the cops raided an after-hours gay bar in a basement just a stone’s throw from the Stonewall, called the Snake Pit. It was a radicalizing moment for many, including Vito Russo.

———

Vito Russo: Among the customers arrested was an Argentinian national, and Diego Viñales was here on a visa and he was afraid that if it came out that he was gay he would be deported, and he jumped from the second floor of the police station window on 10th Street to try to escape and landed on a spike fence. And they had to bring acetylene torches to cut him off. And he was brought to St. Vincent’s Hospital in critical condition, at the edge of death for like three days.

He eventually lived, by the way, and went back to Argentina. I was on my way home from work and I passed St. Vincent’s. There was a candlelight vigil and I remember being handed a leaflet and the leaflet said, “No matter how you look at it, Diego Viñales was pushed.” And that’s when I put two and two together, that in fact he was pushed from that window, he was pushed by society. That if he didn’t have to be so scared of being deported, he wouldn’t’ve jumped, and so for the first time, the organized response reached me on a gut level. And it was the following Thursday when I went to my first Gay Activists Alliance meeting.

———

EM Narration: The GAA had leafleted and organized protests within hours of the raid, including the vigil that Vito mentioned and a march that swept up Morty Manford.

———

MM: I was sitting with some friends, having a sandwich or something, at Mama’s Chick’N’Rib, a popular gay coffee shop on Greenwich Avenue, and this demonstration went by. Hundreds of people with protest signs and chanting and… Obviously a gay demonstration, and said to my friends at the table, “Let’s join it.” Nobody wanted to join it and I said, “Well, I’ll see you later.” I wasn’t gonna let the parade go by.

———

EM Narration: That parade and the vigil have been called the very first “zap.” Marty Robinson is generally credited with coming up with zaps, which were rapid-response, direct action protests. They became a signature of the GAA.

———

BA: The Gay Activists Alliance has begun to confront politicians openly on the streets.

Chanting Crowd: Gay power! Gay power!

BA: They attempted to ask questions of Arthur Goldberg, the Democratic candidate for governor, during a campaign stop at 86th Street and Broadway in Manhattan. When Goldberg refused to respond to the gay people’s questions, they proceeded to shout him down and drive him away. Demonstrators surrounded his car and protested his silence.

Chanting Crowd: Crime of silence! Crime of silence!

Unidentified Protester: You’re a pig! You’re a pig, too, Mister! You’re a pig, too, you know it? You’re a pig, too! You’re a fucking Nazi, baby.

BA: There were further confrontations between the gay people and straight bystanders on the street after Goldberg had left the scene.

Unidentified Bystander: I was talking to Mr. Blumenthal before this happened.

Unidentified Protester: Well, I’ve been talking for five years, god dammit, I don’t care how long you’ve been talking.

BA: State Assemblyman Al Blumenthal stayed on the scene for over half an hour attempting to assure gays that Goldberg was really on their side. Blumenthal promised to work for a change in New York State’s discrimination law to ensure equal protection for homosexuals.

Al Blumenthal: But we’re not going to, we’re not going to change society overnight and we’re not going to change the police overnight, but we are making efforts to change the law and I think we’re going to succeed.

BA: After the incident was over, Jim Owles, president of the Gay Activists Alliance, was asked what he felt the confrontation had accomplished.

Jim Owles: Well, I think we showed Arthur Goldberg that whenever he makes an appearance in the city, he has to be willing to speak to his homosexual constituents. He said that he didn’t think it was an important enough issue, but obviously if he went into a Black neighborhood, he would speak to the Black problems or he would have gotten the same reaction, so we’re just going to let him know that wherever he appears he’s gonna expect the same type of thing.

———

EM Narration: Protests, newspapers, and organizations were popping up everywhere. And as spring turned to summer, preparations for events to commemorate the Stonewall uprising went into full swing.

Craig Rodwell and the other members of the Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee had been in planning mode for several months. Craig’s business, the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop was a nerve center for organizing the march. As a side note, Craig had opened his store in a tiny space on Mercer Street in late 1967. It was America’s first ever gay bookstore.

Anyway, back to the Pride march organizers. They applied for a permit. It was rejected. But the very next day, they were called to a meeting at the NYPD’s third division headquarters. Craig recalled the meeting. And I warn you, Craig uses some very outdated language here. He was speaking in December of 1970.

———

CR: And we walked into this room upstairs, all this brass sitting there, lieutenants, inspectors, and sergeants, and everything. We were informed that a representative of the Mayor’s Office was there and that the Mayor wanted a report back from the meeting as soon as it was finished. And we still to this day don’t know exactly what happened, whether the Mayor found out that they’d denied our permit. But the whole meeting was to go over the route. They had the head of all the precincts there that we were going through, the head of the Parks Department. The inspector was there who was in charge of the raid at the Stonewall. Pine. He just sat there and glared at us the whole meeting. Spooky was the only word for it. He wouldn’t say a word. Just like that, the whole meeting.

And they had a few questions, and the only thing we were concerned with was that we felt we should inform the police that there would be female impersonators there and how would they handle it. And we asked them to realize that this was one day and this was the gay community and they were part of the community and we felt they had a right to exist and if they chose to wear clothes of the opposite sex… And at the same time we realized there was a law against it. However, there are thousands of laws in this city that you do not enforce every day, and we are asking you, in the name of human decency, for one thing, respect for other people, and also a desire for a peaceful day and a peaceful march, not to enforce that law on that day. And their reply was that they of course couldn’t tell us that they wouldn’t enforce it, so we didn’t know what was going to happen.

———

EM Narration: Nobody knew what was going to happen. Gay liberation was breaking new ground with never-before-seen large-scale public protests by LGBTQ people. And the largest ever demonstration by LGBTQ people in the United States was about to take place.

Fifty years ago, Breck Ardery was living in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where he was news director at a local radio station. On a Monday morning at work, he read a small item in the New York Times about, quote, “disorder” outside the Stonewall Inn. Breck knew what he wanted to do next.

———

BA: I moved to New York City in the fall of 1969. It became clear to me that the Stonewall riots had spawned a new gay movement. I thought it would be worthwhile to make an audio documentary on what was going on.

I was going to school and I was working part-time, and so I did it when I could. I just went out and interviewed as many people as I can to find out what was going on with the gay movement and how the whole landscape had changed.

———

EM Narration: Thanks to Breck Ardery and his tape recorder, we can now tell you the story of the first Pride march—on Saturday, June 27, 1970, in Chicago.

———

BA: Mike Barta of Chicago Gay Liberation welcomed the crowd this way.

Mike Barta: I wanna welcome everybody here on behalf of Chicago Gay Liberation on this celebration day, part of Gay Pride week. We’re here because we are gay and we are proud that we are.

BA: In Chicago, as across the country, the gay movement has brought out many people who are new to marches and demonstrations. One of them put it this way.

Unidentified Marcher: I’ve never gone on a march before and I’ll be damned if I’ve ever been in a movement before, but all of a sudden something that cuts the corner of my life and its inner core of being gay and to have some kind of meaning… And I have to say that I’ve gotta be out here no matter what.

BA: When the Chicago marchers reached their destination at the downtown Civic Center there were more speeches. Bill Tries said gays could be in the vanguard of those working to change American society.

Bill Tries: We don’t have to listen to all the rhetoric that explains what’s wrong with this sexist, racist society. We know! Because we are gay, we can be the leaders in the revolution that is going to make this society a better place to live. Gay power!

———

EM Narration: Saturday also saw a small march in San Francisco. Twenty to 30 people marched up Polk Street. After the Chicago and San Francisco marches, on the morning of Sunday, June 28, 1970, Breck Ardery got up, got dressed, and left his apartment in the West Village.

———

BA: I think I was wearing jeans and a T-shirt and a jacket, and the reason I had a jacket on was to carry extra audio cassettes because I was recording interviews and natural sound along the way. And it was a pretty warm day, it was late June, and the jacket was making me kind of hot, but I needed that to carry my equipment.

I went out to the assembly area about two to three hours before the march was scheduled to begin, and it looked pretty disappointing. There were very few people around. But as the time for the march to begin came closer the crowd began to build.

———

BA: People began to gather in the parade assembly area on West Washington Place, just a few blocks away from Christopher Street where angry mobs of gay people had rioted just one year before. The mood today was different. The sun was shining, people were laughing. Meeting old friends and making new ones. The straight press was there with most of the reporters and many perplexed straights trying to make some sense out of what was going on.

But for the most part they were ignored as the gay marchers were caught up in their newfound spirit of pride and assertion. It was a time, a place, and an atmosphere for homosexuals to be together as one united group as they had never been before.

Thousands of gay brothers and sisters were holding hands, chanting, singing, and expressing their love for one another. They were asserting the common bond which holds all homosexuals in America together, a bond which few heterosexuals could ever understand.

As the crowd began to build in the assembly area, Kay Tobin, a reporter for the newspaper GAY, was asked how she felt.

Kay Tobin Lahusen: It looks very good. It’s very dispersed right now, but I think when it’s all pulled together, it will be very strong, very good. And we still have an hour to go after all.

BA: What about the turnout of women so far?

KL: I think it’s, yeah… I think it’s very good, yeah. Very good.

BA: Exactly one hour later, the march began to move.

Chanting Crowd: P! O! W! E! R! What do we want? Gay power!

BA: Out of West Washington Place onto the Avenue of the Americas or 6th Avenue, as native New Yorkers refer to it. For the most part the demonstrators were cheered as they walked through the Village. As the marchers passed the Women’s House of Detention at Greenwich and 6th Avenues a chant of “Free our sisters, free ourselves” welled up.

Chanting Crowd: Free our sisters, free ourselves! Free our sisters, free ourselves!

BA: The march, which had grown 15 blocks long, moved toward 14th Street past Alternate University. The clenched fist salute was raised to the windows of the school and the straights inside the building returned the greeting.

Chanting Crowd: Two, four, six, eight, gays unite to smash the state! Two, four, six, eight, gays unite to smash the state!

BA: The march continued north past 42nd Street, which for years has been one of the most repressive and degrading streets in the U.S. homosexual experience.

Chanting Crowd: Two, four, six, eight, gay is just as good as straight!

BA: Hundreds of different signs were carried aloft during the march, such as “Gay Power,” “This is our country, too,” “We are the people our parents warned us against,” or simply, “Gay Pride.” As the marchers wended their way through Central Park towards Sheep Meadow, the old civil rights song “We Shall Overcome” was heard.

Crowd Singing: We shall overcome… We shall overcome…

BA: As the demonstrators arrived in Sheep Meadow, spontaneous applause and cheering erupted as the group at the front of the march stopped, turned around, and saw the streaming masses crowding up behind them further than the eye could see. Thousands upon thousands of gay people poured into Sheep Meadow from the march route.

The feeling was pervasive. It seemed as if everyone there knew that something of major importance just happened to them and there could be no turning back. The old days of hiding, degradation, and denial of their basic humanity.

Unidentified Marcher 1: Oh, this is tremendous. It’s really great.

Unidentified Marcher 2: There has been nothing like this before and I hope it sets a tone and a trend for the whole future.

Unidentified Marcher 3: Beautiful, just beautiful.

Unidentified Marcher 4: It’s just absolutely incredible. I don’t think the impact will mean anything to me until two days later.

Unidentified Marcher 5: Oh, it’s fantastic.

Unidentified Marcher 6: I feel better.

Unidentified Marcher 7: Brothers and sisters, man, this is really where it’s at.

Unidentified Marcher 8: It was so beautiful. I was in the middle of the march. I couldn’t see the front because it was too far ahead of me, and I couldn’t see the back. I couldn’t believe it! It was just fantastic. It was beautiful, beautiful. I’m just… The happiest day so far of my life.

Unidentified Marcher 9: This is what we needed for a long time.

Unidentified Marcher 10: Marvelous, fantastic. Really is. I feel very liberated because of this.

Unidentified Marcher 11: There must be 15, 20 thousand people here today.

Unidentified Marcher 12: No one expected a turnout like this. This is the best thing that’s happened to the gay movement.

BA: There were many people in Sheep Meadow that day and as the straight world is learning, they were as varied as any large group of people. There were rich and there were poor. Militant and reserved. Young and old. Some had waited many years for this day. Jack Nichols tells of one.

Jack Nichols: Prescott Townsend was there from Boston. He’s a very elderly gentleman, almost 80 years old, and he had come down to march the whole march all the way up, and he has a bad hip, too, I happen to know that. He was one of the first people in this country to start with homosexual civil liberties. Once chained himself to the Massachusetts State Legislature, and old Prescott was there carrying a sign that said “Gay Pride.”

BA: Nichols went on to give his personal reaction to this day.

JN: We stood at the top of the hill in Sheep’s Meadow and watched thousands upon thousands of people come up the hillside and my eyes filled up with tears while I watched all of these people cheering. A very happy, healthy-looking crowd. It was a great experience.

BA: It’s been said that homosexuals will never win respect and acceptance from straight people until they respect and accept themselves. This they’re beginning to do. The road to freedom is always a long and painful one, but on June 28 of 1970 the American homosexual took the most important step toward his freedom, the liberation of his own mind. As one participant said to me, “A new spirit of regained humanity is awakening in homosexuals all over the world and it won’t stop until all of us, all of the millions of gay people, can stand in the sun and be free, as we were for a few hours today.”

———

EM Narration: What Stonewall sparked, the activism of the following year stoked. The number of organizations nationwide rose from 50 to 60 groups before the uprising to more than 1,500 a year later, and 2,500 within two years.

Next episode, we’re heading to the Stonewall Inn for a live show recorded in front of some of you, our amazing listeners, and featuring an intergenerational conversation between activists reflecting on Stonewall’s legacy, and we’ll dive into the historical context with a leading LGBTQ archivist.

I’d like to say a very big thank-you to Breck Ardery for recording the voices of the marches 49 years ago and for so generously sharing them with us. Thank you, Breck.

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: executive producer Sara Burningham, producer Josh Gwynn, assistant producer Mo LaBorde, administrative and special projects manager Inge De Taeye, scoring, mixing and sound design by Rae Kantrowitz, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Denio Lourenco. Thanks also to our intrepid researchers, Brian Ferree and Brian DeShazor. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman. Additional score and our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thanks to the National Park Service’s Stonewall Oral History Project, in partnership with the LGBT Community Center and the Lower East Side Tenement Museum for the clip of Ellen Broidy that you just heard courtesy of the LGBT Community Center National History Archive.

That 1970 audio you heard of Sylvia Rivera was recorded by Liza Cowan. At the time Liza was a producer at WBAI radio, later editor and publisher of DYKE, A Quarterly. And these days, she’s an artist and graphic designer whose work can be found at www.smallequals.com.

And thanks to…

Steve Holt: Steve Holt and—

Margie Smith: Margie Smith of GetMeRewrite…

EM Narration: … for their help recreating those hateful newspaper headlines.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division, the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, and the Pacifica Radio Archive.

Season five of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, Irwin and Andra Press, and our listeners, including Matilda Brooker. Thanks, Matilda.

Sara Burningham: Thanks, Matilda!

EM Narration: Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com, by finding us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, or by emailing us at hello@makinggayhistory.com. We love your letters. Head to our website to find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

So long! Until next time!

###