Season 4 — Introduction

Photo Information

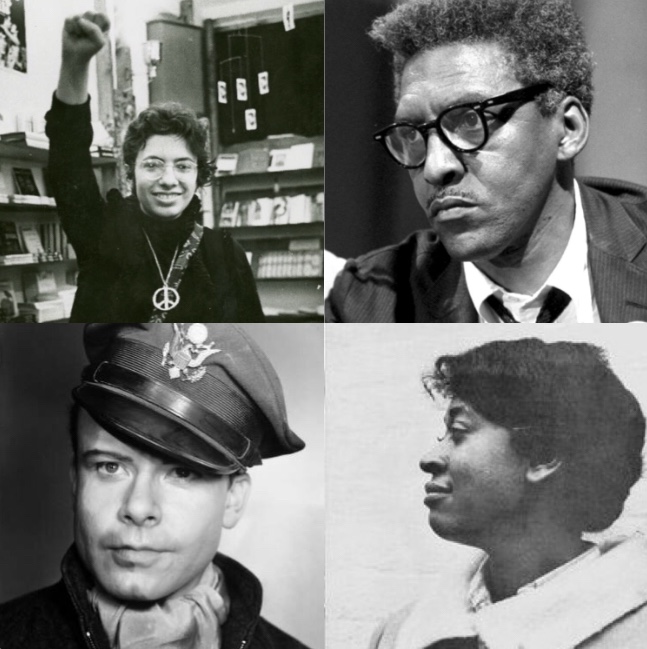

Clockwise from upper left: Martha Shelley at the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, 1969. Credit: Photo by Diana Davies, courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

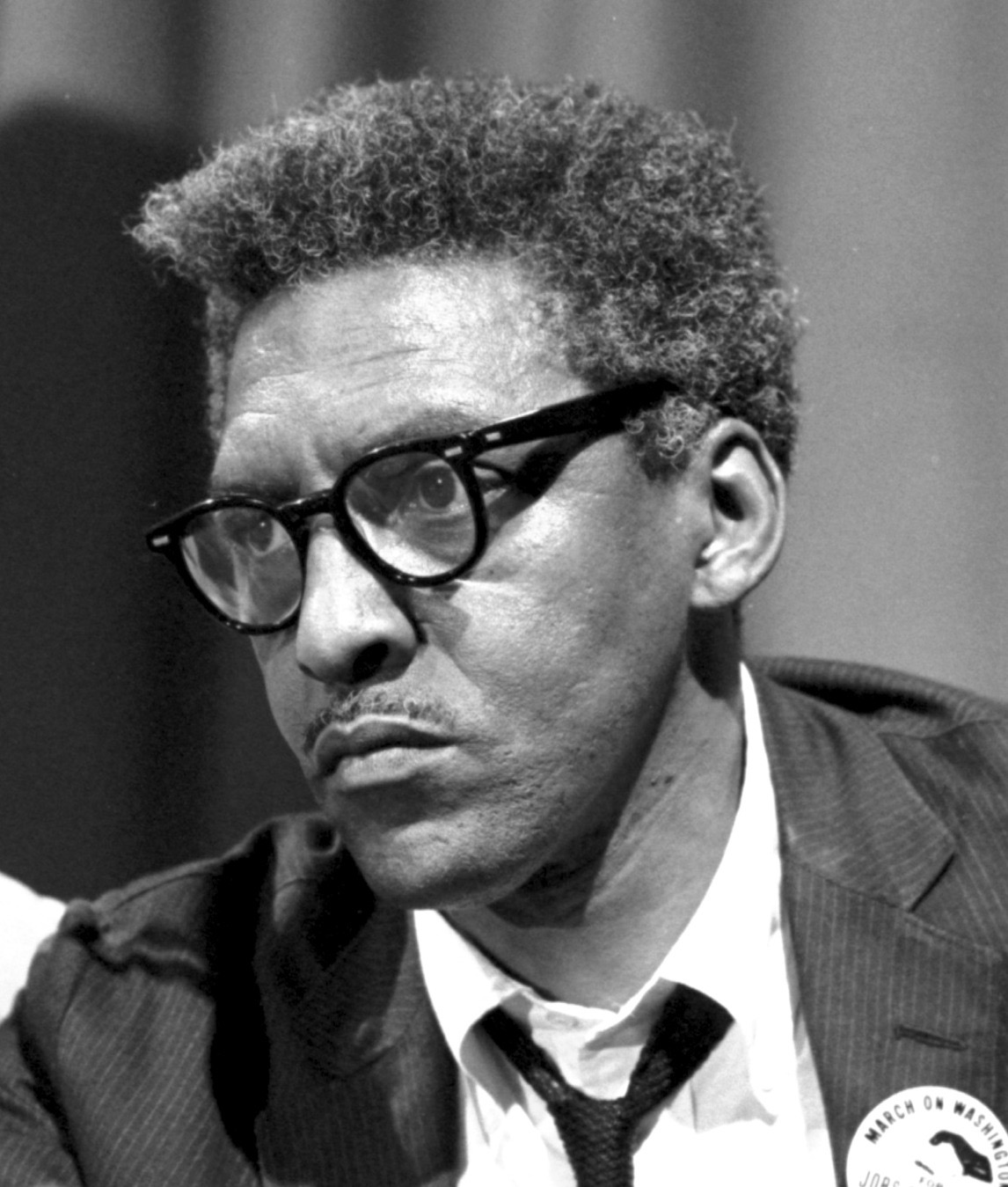

Bayard Rustin at a news briefing on the Civil Rights March on Washington in the Statler Hotel, August 27, 1963. Credit: Photo by Warren K. Leffler, courtesy of Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsc-01272.

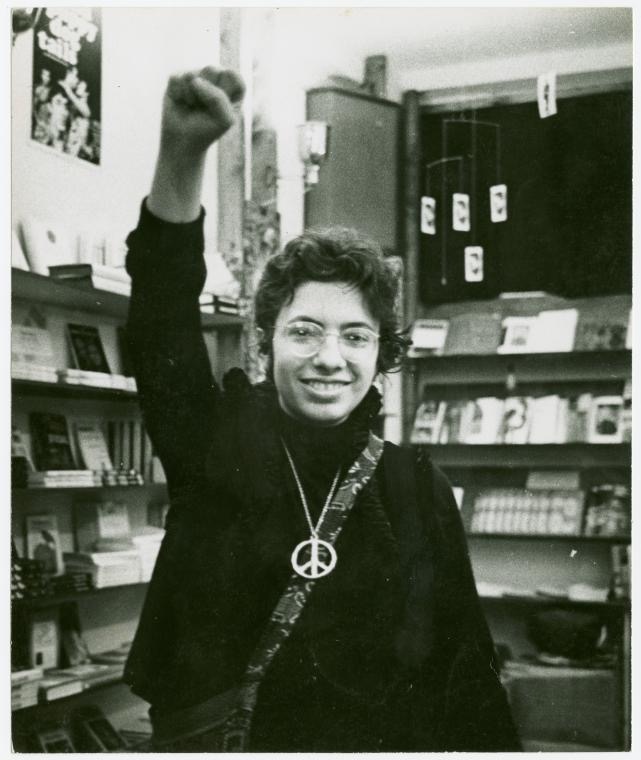

Ernestine Eckstein on the cover of The Ladder in June 1966. Credit: Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen, courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Harry Hay press release still for Clifford Odets’s Til the Day I Die, May 1935. Credit: ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

———

Episode Notes

Our fourth season is about beginnings. So we’re going to start at the beginning and hear from the activists and visionaries who got the ball rolling for LGBTQ civil rights. In this episode, meet some of the trailblazers who will guide us from 1897 in Germany to the eve of the Stonewall uprising, including Magnus Hirschfeld, Harry Hay, Ernestine Eckstein, Bayard Rustin, and Martha Shelley.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and welcome to season four of Making Gay History.

This season is about beginnings—about how the LGBTQ movement began and unfolded in the years before the Stonewall uprising and how the people who got involved in the movement pre-Stonewall got their start. But in the spirit of beginnings, first I’d like to tell you how the Making Gay History project got its start in 1988. Because my journey of discovery is something like the journey we’ll be taking together over the next 10 episodes or so…

It started with a phone call from an editor at Harper & Row, now HarperCollins, who commissioned me to write an oral history book about what was then called the gay and lesbian civil rights movement. I was a journalist with one book under my belt about same-sex couple relationships. Why me, I asked? The editor said he liked how I handled dialogue and he wanted someone fresh to the subject. I was very fresh because I knew almost nothing.

At least I knew where to start. Stonewall. 1969. Everyone knew the movement began there on a hot summer night when the New York City police raided a gay bar in Greenwich Village and queer people fought back.

Or so I thought, before I began my research—before I pored over books, public records, old magazines, and telephone directories to find the early troublemakers who started the movement… Before I crisscrossed the country to interview people who had gotten together in secret in tiny groups as far back as the 1950s… Before I heard first-hand from people who dared to dream about a fairer tomorrow in the 1940s…

And as I followed those threads stretching back through history, I learned that there were some threads that stretched back much farther than the U.S. in the mid-20th century… threads that stretched across the Atlantic to Germany back as far as the 19th century.

By this point in the project I was so overwhelmed by what I was finding that I thought I’d made a terrible mistake in taking it on. How could I even begin to tell all these stories? How could I weave together the history of a movement that had for so long gone undocumented—a history that wasn’t considered a legitimate part of the American story…?

What saved me in the end was accepting that there was no way I could tell the whole story. I’d have to use bits and pieces of our history, told by the people I interviewed. Together their individual stories would give people at least a sense of how that hidden history unfolded over the decades. And I took as my guiding principle some words from Lytton Strachey. He was a founding member of the Bloomsbury group in England in the first half of the 20th century. And he was gay. In the preface to his groundbreaking book, Eminent Victorians, he wrote:

Jonathan Blake Voicing Lytton Strachey: It is not by the direct method of a scrupulous narration that the explorer of the past can hope to depict that singular epoch. If he is wise, he will adopt a subtler strategy. He will attack his subject in unexpected places; he will fall upon the flank, or the rear; he will shoot a sudden, revealing searchlight into obscure recesses, hitherto undivined. He will row out over that great ocean of material, and lower down into it, here and there, a little bucket, which will bring up to the light of day some characteristic specimen, from those far depths, to be examined with a careful curiosity.

EM Narration: So that’s what I did. With careful curiosity, I dipped my bucket into the ocean of our history. Clipping on a microphone and pressing “Record” in dozens of living rooms and kitchens, on front porches, and in a porn theatre in San Francisco, to listen to the people who changed the world and made possible the life I’ve lived as a gay man. And in my little bucket, or on those tapes, were fragments of our history, the stories of our beginnings. And it’s those stories and fragments I’ll be sharing with you in the episodes to come, which will take us from Germany in the late 19th century to the eve of Stonewall in 1969.

So we’re going to start with Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, a pioneering sexologist who founded the world’s first LGBTQ rights organization in Berlin in 1897. And as Dr. Dagmar Herzog, a professor of the history of sexuality, tells us, he was courageous, tenacious, and way ahead of his time.

Dagmar Herzog: It’s not like he’s just there for homosexual male rights. He’s there for the bearded lady, he’s there for the, you know, crossdresser, he’s there for the intersex person, he’s there for the little old ladies who’ve been lesbian lovers for forever. He’s like, he loves them all.

EM Narration: Hirschfeld’s legacy laid the groundwork for the earliest gay rights activists in the U.S. From a short-lived group called the Society for Human Rights, which was founded by Henry Gerber in Chicago in 1924, to the Mattachine Society, founded 26 years later in Los Angeles by Harry Hay and a handful of others… The founders of the Mattachine took inspiration from Gerber and Hirschfeld, and added their organizing skills from their days as Communists—in Harry Hay’s words, everyone was a Red then. They built a highly secretive and quietly radical group. That sounds timid now, but the first steps are often the hardest to take, especially when the people you’re fighting for are a despised and largely hidden minority.

Harry Hay: We ourselves have always been, up until the 20th century, we have been seen as outlaws. And the point is, if you will take this law and even though we burn you and even though we stone you and even though we do all these things, you take the law anyway—what other law would you take into your own hands? You are a danger to the state because you have deliberately take a law and break it. We can’t afford to have you exist.

EM Narration: Harry Hay and the other Mattachine founders weren’t the only ones organizing back then. Have you ever heard of the Knights of the Clock? Chances are you haven’t, and neither had I until 1989, when one of its founders, Dorr Legg, told me about an organization he founded with the enigmatic Merton Bird, an African American man who had a vision.

Dorr Legg: He said to me, “I have been thinking about an organization,” and he described it. Interracial. Um, both male and female couples. And that was what it was about. Would you be interested? I said, Why, certainly, would I… I thought, this is something different.

EM Narration: But as the movement started to take shape, there were those who couldn’t fit in, no matter how hard they tried. Stella Rush came out in 1948 in Los Angeles. Also known by her pen name, Sten Russell, she was a writer who contributed to the earliest gay publications, One Magazine and The Ladder, but she didn’t always feel welcome.

Stella Rush: It sounded to me like the butch imitated the man, and the femme imitated the way we think feminine women should be with their man, and I just simply said, “Supposing you’re both.” “My god,” she said, “don’t say that.” I said, “Supposing you’re both, you got a word for that? I’m both.” She said, “Don’t say that, Stella, that’s almost as bad as being bisexual.” Well, I already knew I was that.

EM: So you’re a bisexual butch femme.

Stella Rush: I’m a bisexual ki-ki son of a bitch butch femme! Oh boy! You know, if I had any place to run, I’d go there.

EM Narration: Stella had to explain “ki-ki” to me in 1989 when I interviewed her. So you’ll find out what it means when we hear her story in a couple of weeks.

While the movement was blossoming on the West Coast in the 1950s, over on the East Coast, Barbara Gittings was finding herself and looking for her people. Later she’d be called one of the mothers of the movement, but when she started out, the obstacles seemed almost insurmountable.

Barbara Gittings: At the time the movement started, which was the late 1940s, the early ’50s, we were considered sick, so the sickness label infected everything that we said and did, and made it very difficult for us to have any credibility for anything we said for ourselves. We were considered sinful so we had to start dialogue with the churches. And we were considered criminal. So we had to deal with the sodomy laws and, by extension, with any of the laws that controlled our lives or did not give us the freedom that we needed. Sick, sinful, and criminal were the three major objective problems that we had to deal with. Now the overriding problem, I think, was invisibility. But there were these three objective things that at least you could get a handle on in some way.

EM Narration: The price of visibility for almost all LGBTQ people was high. In a never-before-heard interview, Bayard Rustin, who organized the March on Washington in 1963, shares how a 1953 arrest on a morals charge (he was found having sex with a man in a car) almost cost him his place in the history of the Black civil rights movement. And it also led to United States Senator Strom Thurmond denouncing him in the congressional record, calling him a “pervert” on the Senate floor.

Bayard Rustin: Strom Thurmond stood up in the Senate of the United States and for three quarters of an hour attacked me as a draft dodger, which was untrue because I was a conscientious objector. He attacked me as a former member of the Young Communist League, which was true, I had been. He attacked me as a homosexual, which of course I was.

Peg Byron: You were the original commie pinko fag of the day, I suppose.

Bayard Rustin: Exactly. Yeah, yeah.

EM Narration: Bayard Rustin is one of the people I wished I’d had the chance to interview, but he died a year before I started my work. So we reached beyond my archive to hear his voice, and others. Voices of people I didn’t interview, but who had important stories to tell about the movement. That interview with Bayard Rustin is thanks to the generosity and meticulous record-keeping of Bayard’s estate, in the person of his partner, Walter Naegle, who you’ll also be hearing from later this season.

We have Barbara Gittings, Kay Lahusen, and the New York Public Library Manuscripts and Archives Division to thank for preserving this next voice. Ernestine Eckstein took a big risk allowing her photo to be published on the cover of the lesbian magazine The Ladder in 1965. Ernestine was the first woman of color on the cover, and she was also in the vanguard of gay people prepared to show their faces in public, in support of the cause. Here’s Ernestine talking to Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen in 1965.

Ernestine Eckstein: I think we have to decide how far we can go toward caring about what heterosexuals think. You know. And we want acceptance, and we want our rights as citizens and as people, but this doesn’t mean that all of our activities and all of our goals are defined by other people’s filthy minds. You know?

EM Narration: Ernestine was on some of the very first pro-gay picket lines outside the White House and in front of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall in 1965. With the men dressed in suits and ties and the women in skirts and heels, they carried coordinated signs with blunt messages demanding their rights. Martha Shelley, who would one day become a radical activist, started out participating in those demonstrations, too. In 1989 she shared with me how public visibility in the ’60s came with compromises that she found hard to take—

Martha Shelley: If you were female you had to wear a skirt. If you were male you had to wear a white shirt and tie. So here we were gay people trying to pass as normal. And I say that ironically because that wasn’t the way we really dressed, but we were trying to show that we were just as good and okay and middle class as everybody else, regardless of what we really were like.

EM: Did that gall you quietly?

Martha Shelley: Oh, yes. It definitely did. I thought it was ridiculous to have to go there in a skirt. But I went and did it anyway because it was something to do that might possibly have an effect. I remember walking around in my little white blouse and skirt and tourists standing there eating their ice cream cones and watching us like, you know, the zoo has opened.

EM Narration: As protests everywhere ramped up in the 1960s, a newly media-conscious band of activists sought out publicity where their predecessors had hidden in secret. Dick Leitsch, then president of the Mattachine Society of New York, led what came to be known as the sip-in. It was modeled on the Black civil rights lunch counter sit-ins in the South, and performed for the cameras at Julius’, a gay bar in Greenwich Village in 1966. That’s three years before Stonewall. The sip-in was designed to challenge laws that made it illegal to knowingly serve alcohol to homosexuals.

Dick Leitsch: “I can’t serve you if you’re gay. You know that. You’re with the Mattachine Society. You know it’s against the law to serve homosexuals. We got busted last week, we got cops sitting in the damn door, we gotta go to court, na na na na, we can’t serve you.” And I looked around at all these sissies sitting at the bar, and I thought, Carry on, girlfriend. The bartender was straight. But, so we didn’t get served. And so the press, you know, what’s-his-name took these pictures, and the Times did a story and the Post did a story, and all that. And so we got our coverage, and we were very pleased with ourselves. And it became kind of an issue, you know, like, how can you not serve food and liquor to homosexuals, don’t they eat and drink? And people were talking about it.

EM Narration: And three years later, they did more than just talk about it, when queer anger erupted outside the Stonewall Inn and a new chapter of history began. But we’re saving that for season five. For now, let’s start at the beginning.

I love Lytton Strachey’s little bucket theory of exploring history. It really helped guide me as I listened attentively to hundreds of hours of oral histories. And I heard an echo of Strachey’s theory in something Barbara Gittings said, and it reinforced for me why our stories matter—all of them.

Barbara Gittings: All of our histories are lacking the little events and the little activities that never got noted in the papers, what few there were at the time, but that really built the movement. Not a mass demonstration in Washington. Fantastic. But before that, there were all sorts of little things that never got noticed that were being done. If it isn’t recorded somewhere it didn’t happen. And I think that’s really unfortunate because I’d like to see some of it recorded.

EM Narration: So off we go, with our little bucket, to dip into the stories that built a movement, from the very beginning.

Making Gay History is a team effort. Thank you to executive producer Sara Burningham and the rest of the Making Gay History crew: producer Josh Gwynn, production coordinator Inge De Taeye, social media producer Denio Lourenco, photo editor Michael Green, and our guardian angel, Jenna Weiss-Berman. A special thank-you to Jonathan Blake for his gorgeous recitation of Lytton Strachey’s guiding principle. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. Season four of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, and our listeners, including a generous gift from Andra and Irwin Press.

And while I’ve still got you… Guess what? There’s a new way you can support this show. By wearing us! Click on the merchandise tab on our website and you’ll find Making Gay History t-shirts, tote bags, tank tops, and hoodies. And to find out what we’re cooking up next, subscribe to our newsletter. You can find the link for that and all our previous episodes, as well as archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people we feature at makinggayhistory.com.

So long! Until next time!

###