Ruth Simpson

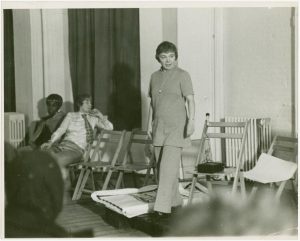

Ruth Simpson at the Daughters of Bilitis loft space, New York City, 1971. Credit: Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen, courtesy of the Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Ruth Simpson at the Daughters of Bilitis loft space, New York City, 1971. Credit: Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen, courtesy of the Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Episode Notes

There’s a war on out there.

That was Ruth Simpson’s Stonewall takeaway—and she was ready to fight. But when Ruth pushed the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis to be more political, the FBI and the police took note.

Episode first published October 24, 2019.

———

From Eric Marcus: One of the joys of producing this podcast is that I have the opportunity to share stories from my archive that didn’t make it into my Making Gay History book. I recorded a little more than a hundred interviews, but only 62 made it into print, and I’ve always felt guilty about the stories I left on the cutting room floor.

Some of the oral histories I left out, like my interview with Marsha P. Johnson, didn’t yield enough usable material for a book chapter (although her joint interview with Randy Wicker worked well in a podcast episode). Other interviewees simply weren’t good storytellers. And still others I left out because the period of history they spoke about was already covered by someone else I’d interviewed. This was the case with Ruth Simpson, whose tenure as president of the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) began just before the Stonewall uprising and lasted into the very turbulent two years that followed.

Ruth’s story illustrates the challenges faced by old-line homophile organizations as they tried to adapt to a radically transformed post-Stonewall environment. As Ruth pushed DOB’s New York chapter to become more engaged in political activism and public demonstrations, the group was forced to confront both internal dissent and external threats from FBI infiltrators and police harassment. Ruth’s story also highlights the continuing perils faced by established professionals who risked their careers as they fought for gay liberation and equal rights.

To learn more about Ruth Simpson and her experiences as president of the New York chapter of DOB, have a look at the episode notes that follow below.

———

Get started by reading Ruth Simpson’s obituary in the Los Angeles Times and watching this interview, which was recorded for the Lesbian Herstory Archives’ Daughters of Bilitis Video Project (Ruth is interviewed with her partner, Ellen Povill).

Ruth joined the New York chapter of DOB in the late 1960s and soon volunteered to serve as its education and program director. She was later elected president and served in that capacity from 1969 to 1971. To learn more about DOB, read Marcia M. Gallo’s Different Daughters—A History of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Rise of the Lesbian Movement and be sure to listen to our episode with DOB co-founders Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. Ruth first heard about the New York chapter of DOB in a radio interview with its then-president, Martha Shelley, who was featured in her own MGH episode here.

During her tenure as president of New York’s DOB chapter, Ruth found herself the target of harassment by the New York City police. In the episode, Ruth recounts a confrontation with police officers when they entered the space where DOB was holding its meeting—a space lent to them by the Corduroy Club men’s discussion group—without a warrant. The incident was reported on at the time by Gay Flames, a publication of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). Find out more about the NYPD’s surveillance of gay and lesbian groups on the NYC Municipal Archives website.

Like many other LGBTQ organizations at the time, DOB was also subject to surveillance by the FBI. You can read declassified FBI files on DOB going all the way back to the 1950s here and here.

As DOB president, Ruth soon moved her chapter’s headquarters to a new space in Soho where they could have meetings and hold dances. Ruth, DOB, and the new loft were profiled by the New York Times in a long 1971 piece titled “The Disciples of Sappho, Updated.”

In the early 1970s, Ruth was involved in many street protests, including the 1971 Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) “zap” against Fidelifacts, which she discusses in the episode. In a bizarre moment of serendipity, the demonstration appears in the opening sequence of the film Shaft (you can view it here, starting at 2:20). In addition to LGBTQ zaps, Ruth also participated in feminist protests. In 1972, she was charged with disorderly conduct and resisting arrest during a WARN (Women Against Richard Nixon) demonstration.

Ruth was featured in Kay Tobin Lahusen’s 1972 book The Gay Crusaders, a collection of interviews with gay liberation leaders. The audio of her original interview is kept at the Wilcox Archive in Philadelphia and the New York Public Library. To learn more about Kay Tobin Lahusen, check out our two episodes (and accompanying notes) with her and her partner Barbara Gittings here and here.

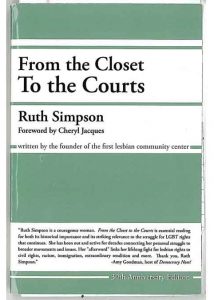

In 1976, Ruth moved to Woodstock, New York, and published From the Closet to the Courts: The Lesbian Transition, a detailed memoir of her time in the gay rights movement.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus: Does she like to be held and does she—

Ruth Simpson: Yeah. Flora!

EM: I can hold her in my lap.

RS: No, that’s all right. Flora, away from the table, please. No, he’s, he’s—Flora!

EM: I’d be delighted to hold her.

RS: If you want to, but she’s not supposed to do this.

EM: She’s not?

RS: No, but that’s all right…

EM: Okay, come on, up!

RS: Miss Smart.

EM: She knows a softie when she finds one.

RS: I think she likes your mustache.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History!

In the months and years after the 1969 Stonewall uprising, thousands of radicalized young activists founded hundreds of new organizations across the country dedicated to the fight for gay liberation and equal rights. For old-line homophile organizations like the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society, the transformed landscape brought new energy, but also very real challenges.

Ruth Simpson was born on March 15, 1926 in Cleveland, Ohio. She joined the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis in the late 1960s. By then she held a top executive position at a high-profile public relations firm.

The Daughters of Bilitis—or DOB for short—was the country’s first organization for lesbians, founded in San Francisco in 1955. Ruth attended DOB’s social gatherings and discussion groups. And before long she took over as president of the chapter, opened a community center for lesbians, and pushed the organization to join post-Stonewall protests challenging discrimination. The chapter’s more political agenda led to internal conflicts, unwanted attention from the police, and meddling by the FBI.

So here’s the scene. It’s the dead of winter in 1989. I’ve just taken a two-hour bus ride from Manhattan to Woodstock, New York, a small town nestled in the Catskill Mountains. Ruth picks me up at the bus station and we drive a short distance to the small, cozy house she shares with Ellen Povill, her partner of many years, and Flora, their very friendly poodle.

Ruth is a small woman, although she’s quick to note that she’s not as thin as she once was. She’s in her early 60s and has short gray hair. Ellen is several years younger. She’s tall and thin, made even taller by a thick crown of brown hair.

As usual, I’m starved. Thankfully, Ruth has prepared lunch and we talk while we eat. Ellen mostly hovers in the background, occasionally pouring wine for Ruth and ginger ale for me. Before I dive into my sandwich, I clip a microphone to Ruth’s sweater and press record.

———

EM: Interview with Ruth Simpson and Ellen Povill, February 9, 1989. Woodstock, New York, 1 p.m. Tape one, side one. Interviewer, Eric Marcus.

RS: I was at that time totally closeted. And then I heard a radio interview with Martha Shelley, who used to be active in the gay movement, and she gave the name of Daughters of Bilitis and the address and the time and day of the meeting. So I just went there one night, and, uh, felt I had come home to my people.

EM: Can you describe that meeting for me?

RS: It was, you know, on a very dark street in Manhattan. It was on the second floor…

EM: Were you fearful going there that first time?

RS: Mm-mm. No. Let me explain about my being closeted for so long. It was, I never, never had guilt feelings. Or never thought, I’m so peculiar, what am I doing in the world? But I was very aware of the sociological dangers involved with getting a job. And of course I held, at the time I went to DOB, I held a top executive position on Madison Avenue.

EM: So you had to be concerned going because of your job.

RS: You put it in a nutshell, which is where it belongs.

EM: If you had been open, you couldn’t have gotten your jobs.

RS: No, I’ll, I’ll tell you what happened about when I did come out of the closet. Anyway, so, no, I wasn’t frightened. I felt a certain sense of adventure to walk in the room and look around you and see a hundred women and say, My god, there are this many of us in Manhattan?

EM: Do you remember what was discussed at that meeting?

RS: Mostly it was a rap session. At that time DOB was not very political. There was a lot of talk about women who thought they were straight but were having doubts. There were a lot of stories about what happened when I told my parents. It was pretty much all on a personal level.

EM: I assume a lot of people who attended meetings were people who were risking their, their careers.

RS: Mm-hmm. Absolutely. A lot of women were frightened to be there.

EM: Were some of them married?

RS: Oh, yes. Yes. Yes. There were, there were straight women who came.

EM: Straight meaning they were straight or they were leading straight lifestyles.

RS: They were living straight lifestyles. Thank you for making that fine distinction. Anyway, they talked a little bit about organization, administration of the organization. And I said that I would be program director, after about my third meeting.

EM: So you got very heavily involved very fast. You became president in—

RS: In ’69.

EM: You became president in ’69. When in ’69 did you become president? Was it before the riot at Stonewall?

RS: Oh yeah.

EM: What did, what did Stonewall represent, or did it not represent anything?

RS: Oh, no, it, it very definitely represented, Hey, there’s a war on out there. And keep in mind when you have… In those times, a lesbian organization might have three to five hundred women at a weekend dance. You had a lot of people that didn’t want to hear from politics. And some of the women really resented it when we started to get political.

EM: Where did your political interest come from?

RS: Well, I was very peripherally involved in the Black movement. I would go out and ring doorbells and get people to join NAACP, all of this sort of thing.

EM: This was during the same time, or this was earlier?

RS: Earlier. My parents, fabulous, fabulous people, were very active in the very early days of the labor movement in this country. When I was 12, I saw my first police brutality on the picket line, saw my father get beat. Held my mother’s hand and ran from tear gas. So I had the, all that kind of thing in my background, so I sort of just stepped back. And for more years than I should have.

But then when I went to DOB, I thought, I’m going to try, try to see… It shouldn’t be that others have to, other, the young people have to go through this sort of pain, this psychic pain, and the deceit and the lies and the, the broken families.

We ranged in age from, like, 18 to 72. It was wonderful.

EM: At the time you were, there were dances every week, or—

RS: Yeah.

EM: Where did you hold the dances?

RS: Well, in ’70 we got the loft down in, in Soho. We were so glad because we knew how important it was to have a home. We ordered lumber, built partitions, we made a kitchen, we made a library. I mean, it was a great space.

EM: That was a critical part of your, of your organization, the social function.

RS: Oh, yeah. We started to get more and more political.

EM: Can you characterize what more political meant, what, what was that?

RS: We, instead of saying, “Well, I so-and-so, and my parents,” we started talking about “we.” We need, we need to help each other on a broader scale. We need to understand who, what institutions are responsible for the, for continuing this oppression.

I don’t know if you know about the Fidelifacts demonstration?

EM: No, tell me about that. What was that?

RS: Fidelifacts was this organization, it was headed by an ex-FBI man. He’d made a speech that was quoted in the Wall Street Journal. They screened applicants to make sure they weren’t homosexual, for major corporations. And he had this line, “If it walks like a duck, if it quacks like a duck, if it looks like a duck, then it’s a duck.”

So, we decided to have a demonstration outside of what we called Fiddle-di-Facts. And GAA rented this marvelous duck costume. And we met on Times Square, we had our signs, “Fiddle-di-Facts oppresses the homosexual,” I forget all the signs we had. And we had a bullhorn. And so we started marching. We walked over to their offices, went up into their offices, and said, “We want to meet with whatever-his-name-is, the head of—” “Well, he is out of town.” He wasn’t there. And we wanted to cause a stir but we didn’t want to be arrested because these arrests took a lot of time out of your work, out of your—

EM: And you were still, you were still at your advertising firm.

RS: Yeah, yeah.

EM: Was this on your lunch hour? Was it—?

RS: Yeah, this was all, we did a lot of lunch hour, a lot of lunch hour demonstrations because—

EM: So as far as your colleagues knew, you left the office to go lunch. But where were you?

RS: Yeah, I was walking beside a duck.

EM: What kind of feelings were you left with after something like that? It must have been—

RS: Oh, the adrenaline was really surging. It was good feelings, good feelings.

Anyway, so that’s the sort of thing that we were involved in. And one night I had, I had some of the men who had been picked up in the backs of cop cars and beaten and left out on the piers, to talk about what, what happens. And they were men from a political organization. And I said, “I don’t want to predict negativity, but once we start really getting political, we are going to face this sort of thing,” and sure enough we did.

I mean, the first time cops walked into DOB, and that was before we had the loft, I was scared. I didn’t have a dress rehearsal for this.

EM: Why did the police show up at—

RS: Alright, we had, we had joined GAA in some of their demonstrations.

EM: In ’69.

RS: Mm-hmm. And at this time, in my fine Madison Avenue office, the phone rang and I answered. He said, “Hello, this is Sergeant Kelly from the 19th Precinct and I’d like some information. You’re president of DOB?” I said, “Just a minute, what, how did you get this number?” He said, “Oh, we have our ways.” And he said, “Well, I’d like to know how many women are members, what your dues are.” I said, “You can get any information that you are supposed to have from our attorney.” This was, like, we met on Thursdays, this is, like, on Tuesday. That Thursday, the door came open and there are two cops. Well, the women just froze. We were in the middle of a discussion of how the psychiatric profession oppresses us, organized religion oppresses us, how the police oppress us, how we have to hide our basic identities where we work—

So I walked toward the cops. I had no idea what was going to happen. I walked toward them. And I said, “You are here illegally. Do you have a search warrant? And who are you? I want your badge numbers.” And the one had, was chewing gum and had a squawk box going really loud. And I said, “Can you turn that down?” He just, you know, he ignored me. And so they came walking, and I was, found myself walking backwards. And Ellen, Ellen was there. In fact, I had just met Ellen.

EM: Ellen Povill.

RS: Yeah, this, this, this treasure here. Anyway, they said, “Okay, get your coat. We’re taking you in.”

EM: You?

RS: I said, “Why?” I said, “I’m not going anywhere with you until I talk to our lawyer.” And he stood, he had his billy club, and he stood holding it like this and he said, “Look, lady, I don’t want to have to break your horn.” Horn is police-ese for the skull. And he said it softly. I said, “What did you say? Would you, I didn’t hear you.”

You know, I didn’t, I really, I didn’t know what, how feisty I could be and be legal. And he was starting to get very annoyed.

So he said, “Okay, I’m writing you out a summons.” And it was a summons to appear in court for a violation of the occupancy sign. He said, again, he said, “All right, come on. I’m taking you in.” Seventy women stood as one person and said, “If you take her, you take all of us.” Well, these two cops just blanched. You know, what were they going to do with a patrol car and 70 women? I mean, it was, it was fabulous.

The first appearance in court, Sergeant Kelly didn’t appear. This is part of the harassment. They get you to come to court and then the, the so-called arresting officer doesn’t show up. So we had to come back a second time, and by this time we had arranged a big demonstration. We had the courtroom full of people. We called the press. And when they said, “Will the defendant please stand up and come forward,” the whole courtroom, holding hands, the whole courtroom stood up. So the judge was… Oh, what, what a case he was. He saw this and he immediately stood up and in the most dramatic gesture with robe flowing, he said, “This is not theater!”

So anyway, so the charges were ultimately dismissed. This was what they did. They would bring people into court on charges and then dismiss them, and then bring them in again and dismiss them.

EM: What purpose did it serve? Who was—?

RS: Harassment.

EM: And this was orchestrated by whom? Was it, it was government-sanctioned harassment?

RS: Oh sure. Of course. The, for some reason the New York Police Department was very threatened by gay women, by lesbians. GAA and DOB had this arrangement, because we knew if cops came to GAA they’d soon be coming to DOB, so they would send runners over, and if we had cops… This was how often they came to harass us.

EM: Was this once a month? Once every few months? Twice a year?

RS: Maybe once every month and a half. And then we would send runners over to let them know the cops were here at our place. Anyway, that sort of galvanized DOB, the women—

We were also infiltrated by… We knew one woman was FBI.

EM: How did you know?

RS: Once DOB was disrupted, that woman turned up in another organization. A totally different persona, pulling the same tactics.

EM: Another gay organization.

RS: Yeah. And her whole thing was disruption. Disrupting… You know, that’s the, that’s the classic handbook strategy. Disrupt. You begin to realize and to recognize the, straight out of an agent’s handbook, some of the tactics that were used.

Our phone was tapped. At that time, through, believe it or not, a Mafia connection, we got a number that you could call, and if your line was tapped, you got a siren sound. So we knew our phone was tapped.

Now, at our apartment on Central Park West, Ellen, I was at home, and Ellen was at her office, and she called to say, she’s going to be working late, and how was my day and we chatted, and at the end, I said, “I love you,” and she said, “I love you,” and a man’s voice said, “I love both of you.”

EM: My god…

RS: Then we started to getting harassment calls that were scary as hell. This one man called and said, “You know, there are plenty of people working with the FBI and the CIA, and they want to know about people like you. And sometimes people like you end up dead.” Oh, it was, it was heavy.

EM: What happened with your job at this time? Were they aware at work what was going on?

RS: No. At this point I still was not, I still had not come out at my job. Well, I’d been on radio interviews, BAI… My name had been around and I was just lucky, you know…

EM: So anyone researching could have found—

RS: Yeah. Yeah, and at this time it was known that there were gay and lesbian groups and they were titillating to the average viewer. ABC called. So I went to this woman vice president, and said, “I don’t mean to unburden my personal life on you.” But when I told her who I was and why I was telling her, because I was about to appear on a network—

EM: And she was your superior.

RS: She was an executive vice-president. And she said, “Well, I think you’re very courageous, and I’ll be watching.” I said, “I, you know, I owe you, I have an ethical obligation. I want you to hear from me rather than from a client who happens to be watching and says, ‘Guess who we saw? And guess what she is?’” And we had very big fancy clients. So anyway, I went and was on the show.

EM: What kinds of things did they ask you?

RS: They asked all the usual things, you know.

EM: Like?

RS: Like, “When did you first discover that you were a lesbian?” And at this point I was being very light with it. I said, “It’s very hard to say. Could you tell me when you first discovered that you were heterosexual? If you are?” You know, and it was all, but it was, it was all light, it was not, not hostile, and I conducted myself with what I thought was great dignity. So I got back to my office, and it was an early morning show. So I got in the office a little before 9, and about 9:15 the phone rang and it was the vice-president saying, “I saw the show, I thought you were very eloquent and elegant and I admire your courage.”

Two weeks later I was fired. I was their top woman PR executive. I never got another job in PR.

EM: What did you do then for a living?

RS: I worked as a waitress.

———

EM Narration: After her stint as a waitress, Ruth Simpson found a home at a more accepting company, first as a receptionist and then as a textbook writer and anthology editor. In 1976 Ruth and Ellen moved to Woodstock, New York. Ruth became president of the local library, taught writing workshops for older folks, and for two decades hosted a weekly show on local access TV called Minority Report.

Ruth left the Daughters of Bilitis in the spring of 1971, resigning along with the rest of the New York chapter’s leadership as members fought over the direction of the organization.

As my 1989 interview with Ruth was winding down, the conversation turned to Ruth and Ellen’s other pets, two deer mice named Tarzan and Viva, and getting to the bus stop in time for my return trip to Manhattan.

I was about to turn off the tape recorder when I asked Ruth if there was anything else she wanted to share with me. And there was. She told me about a phone call she got from her old boss, the one who had praised her for her ABC television appearance. This was about three years after Ruth was fired.

———

RS: She called me and she said, “Ruth, I have to…” She said, “I haven’t been able to live with myself.” She said, “It wasn’t my decision, but I was, I was the instrument by which you were fired,” and she said, “I really have great admiration for you. And I want you to know that I’m a lesbian and have been for all my adult life.” At that time she had lived with this woman for, I think, about 12 years…

———

EM Narration: Ruth Simpson died in 2008. She was 82. Her partner, Ellen Povill, still lives in the home she shared with Ruth in Woodstock, New York. Ellen is 81 and works as a videographer. In a recent phone call with Making Gay History, we asked Ellen if she had a partner. She explained that after 37 years with Ruth she wasn’t interested in dating. She said, “I’ve been with the best.”

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: our new senior producer Nahanni Rous, producers Josh Gwynn and Janelle Anderson, deputy director Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Jeff Towne, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Denio Lourenco. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman and our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season six of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Small Change Foundation, Irwin and Andra Press, and our listeners, including Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson. Thanks, Mary! Thanks Lee!

Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com, by finding us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, or by emailing us at hello@makinggayhistory.com. We love your supportive emails, so don’t hesitate to write.

Head to our website to find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature. And please subscribe to Making Gay History wherever you get your podcasts.

So long! Until next time!

###