Revisiting the Archive — Shirley Willer

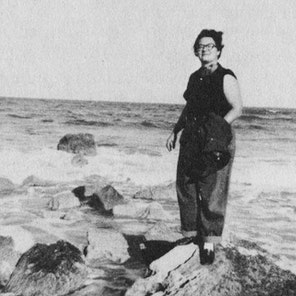

Shirley Willer in the mid-1960s at the beach in Atlantic City, where she and her partner, Marion Glass, had gone to scout a location for a Daughters of Bilitis outing. Credit: © Lesbian Herstory Archives.

Shirley Willer in the mid-1960s at the beach in Atlantic City, where she and her partner, Marion Glass, had gone to scout a location for a Daughters of Bilitis outing. Credit: © Lesbian Herstory Archives.Episode Notes

“I’ve spent a large percent of my life being angry.” That was Shirley Willer, reflecting on the death of a close friend and fellow nurse who in 1947 received fatally inadequate hospital care because he was gay. Shirley channeled her anger into activism in the early homophile movement—let’s listen to her story as we face the challenge of what to do with our own anger during this pandemic that has upended our lives.

Visit our season two episode webpage for background information, archival photos, and other resources.

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

I’m recording this fourth episode in our “Revisiting the Archive” series on Thursday, April 8, four weeks to the day since my partner Barney and I started sheltering in place. And just a few days since the coronavirus likely claimed the life of a 40-year-old next-door neighbor. From what I’ve been reading, the wave of infections here in New York City seems to be cresting just as the threat mounts in other parts of the country.

In an almost-daily ritual now, I talk with my brother after he gets off his shift at the hospital where he works, about five hours south of New York City. He’s an emergency room administrator. Night before last we had a long, anguished conversation about how he and his co-workers aren’t getting the proper gear they need to protect themselves from getting sick. The doctors and nurses are thankfully well-supplied, but my brother and his administrator colleagues aren’t considered frontline workers, even though they’re in close contact with patients arriving in the emergency room. One of my brother’s colleagues was just diagnosed and is recovering at home.

My brother is understandably scared—and angry. And I’m scared for him and angry, too. It shouldn’t be like this. So, what to do with that anger? As I talked with my brother, Shirley Willer came to mind. Shirley was a nurse who saw firsthand what happens when the people we care about die because of incompetence and inequality.

I interviewed Shirley back in 1989 because of her role in the early homophile movement where she served as national president of the Daughters of Bilitis, an organization for lesbians founded in 1955.

But that’s not the part of Shirley’s life that’s on my mind now. I’m thinking farther back, to Shirley’s life in 1940s Chicago and how anger inspired her to make change and force people to do the right thing—or to at least try.

So here’s the scene. It was a warm, humid fall day when I arrived on the doorstep of Shirley’s one-story house in a working-class neighborhood of Key West, Florida. A young woman in cutoff shorts and a tank top answered the door and led me to a sunroom at the back of the house, where Shirley was seated in a large wheelchair. Her hair was mostly gray and cut in a flattop style. She peered at me from behind thick Coke-bottle glasses, giving me the once-over. The way she looked, and the way she looked at me, was a little intimidating.

She set her lit cigarette in an ashtray that was piled high with a pyramid of butts. Budgies flitted in their cages on her porch and chirped like a half dozen smoke alarms being tested. But when Shirley reached out to shake my hand—remember shaking hands?—her warm smile set me at ease. I unpacked my equipment, clipped the microphone to her blouse, and sat down in a chair opposite her. I pressed record.

———

Shirley Willer: I may have to remove this little guy or he’s gonna be taking over the mic. Get over here. You don’t want to, I know.

I’m a nurse, and I discovered I was gay—we’ll use the word, it’s easier nowadays—sitting in a classroom listening to a lecture on mental hygiene.

Eric Marcus: What was the lecture? What did she say in the lecture?

SW: She described what a lesbian was like. I said, “Oh, gee, I’m one of those things!”

EM: What was her description?

SW: Um, how you were not attracted to men. How you had these violent crushes on women.

EM: Where in 1941 would you have read about such things or heard about such things?

SW: Well, I know there were copies of The Well of Loneliness around. Because after I… When I found out I went home and told my mother. And she was able to get a hold of a copy of the book. Then I started looking up words in the dictionary and then the encyclopedia.

EM: And what did you find?

SW: Not very pleasant descriptions. Pervert. It was a perversion of the natural instincts of the human animal. And at that time it was considered a criminal act. In fact, I remember being picked up by the front of my shirt and slapped back and forth by a policeman because I was on the streets at 11 o’clock and I had on slacks, women’s slacks and a sport shirt.

EM: A policeman?

SW: Policeman. I was walking down Rush Street trying to find a gay bar that I’d heard of. I had a woman’s shirt on and women’s slacks, but obviously made as tailored as possible.

EM: Tailored clothing means what?

SW: A Brooks Brothers suit. Now, I’m not talking about a man’s suit. I’m talking about a woman’s suit. I had massive muscles here and they had to rebuild the top here. Oh, that cost a fortune. I think it cost me all of $120 to have it tailored.

EM: Did the policeman say anything when he was hitting you to indicate…?

SW: He called me names. “God damned pervert. You queer. You SOB,” and so forth.

EM: And you couldn’t call the police, could you?

SW: No, I couldn’t call the police. It was a policeman! But, in fact, I finally did find the bar. I’m not sure, but it might still be there. It was the Seven Seas.

EM: Was this the first bar you went to?

SW: Yes.

EM: So you got slapped around the first time you were on your way to a bar?

SW: The first time I was on my way to a bar.

EM: Stupid question here. Was that frightening?

SW: I wasn’t frightened, I was angry.

EM: Why were you angry?

SW: He had no right to do that to me. And that’s been my attitude all of my life. They have no right.

EM: How did you even find the bars? How did you know about these things?

SW: Well, you see, I started out as most people do, thinking I was the only one. Then I realized there had to be more out there or there wouldn’t be any kind of books. And there wouldn’t be any definitions. But of course I didn’t know how to find them.

When the war ended, all these corpsmen came back.

EM: These are the male nurses who came back.

SW: They were corpsmen in the Navy and in the Army. And then, of course, when they were working in the hospital, we met each other. And most of ’em were pretty flaming queens.

EM: When you say these guys were flaming, um, can you describe for me what that means?

SW: Today they would call it being extremely swish. They, um, the mannerisms were very limp-wristed. Even at work, they would emphasize feminine characteristics. Thank goodness the hospital was, simply didn’t seem to pay much attention to it. They did their job right, they did their job right, that’s all that mattered.

At that time, the big events in Chicago were the Halloween balls. Aragon and Trianon. They were huge ballrooms. One on the north side and one on the south side. And every Halloween all bars were off and everybody went in costume. And all of us would get tuxedos and…

EM: All the women…

SW: All the women. And dress in our butchiest styles and we’d all go to the balls. The Aragon was on the north side. The Trianon was on the south side.

These two particular big events were, again, run by the Mafia. And we’d hire limousines, you see, and get a police escort through the crowds in order to get inside and, uh…

EM: This was the one time of year that gay people could be gay.

SW: One time of year that gay people could be gay. But it was the only visible sign that there literally were thousands and thousands of gay people in the city.

EM: When was the first time you went to this, in the 1940s?

SW: It was shortly after the fellas got out of the service, because I remember they dressed me.

EM: How did they dress you?

SW: In a tuxedo. And tied my tie. And put makeup on me. I’d never worn makeup in my life! All the fellas wore dresses.

EM: When did you become aware that there was any kind of organized…?

SW: There wasn’t much of an organized movement. The only organized group that I could find out about was ONE, which was more a literary thing.

EM: And this is already by early 1950s.

SW: That’s right.

EM: So what happened during the 1940s?

SW: Before then it was pretty much on our own volition that we would… There were so many young women that were being thrown out of their homes, so we started our own little informal groups. And we would take in all the kids that got kicked out in the street. And we would keep pushing them to stop trying to hide it, um, be themselves. I believed that you should stand up and be counted.

EM: Wasn’t that dangerous for most people?

SW: It’s always dangerous for anyone who doesn’t have any money in the bank.

EM: But weren’t many of them in danger of losing their jobs?

SW: It would depend on the job they would take. Now, a majority of them wouldn’t take jobs where they were endangered. They would go for the dirty jobs, the rough jobs. Running an elevator. I remember one in particular, a very bright girl. But the only job she could get was running an elevator ’cause she wouldn’t wear a dress. So we didn’t call ourselves any particular group.

EM: How did you come in contact with Pearl Hart? And Pearl Hart was an attorney?

SW: That’s right. Talking to some of the men is where we first heard of her. There was this group of about six of us, six women. And we wanted to form some kind of an organization. So we went to see her. And we asked her, you know, how do you go about doing such a thing? She said, “You don’t.”

EM: Why did she say, “You don’t”?

SW: Pearl at that time was like everyone else. She felt that people would get farther by simply doing things quietly without announcing themselves, without having large formal meetings and so forth. Um, she was a grand old lady.

EM: Was she herself a lesbian?

SW: Ah, yes. Again, I never slept with her so I can’t swear to it.

EM: Right.

SW: But she also wore Brooks Brothers suits, except that hers were tweedy.

EM: So that was one of the indicators.

SW: That’s right. It was a very sad time to be alive.

EM: Why is that? Why do you say that?

SW: Well, for example, we had one young man who was studying medicine. He was working as a nurse. He worked the 11:00 to 7:00 shift.

EM: 11:00…

SW: Midnight until 7:00 in the morning. Then at 9 o’clock he would have his first class. And, uh, so he would go home and he’d shower and a friend of his would pick him up and they’d go to class together. Well, he fell asleep while he was waiting one day and by the time his friend got there the couch was totally in flames.

EM: He’d been smoking.

SW: Yes, and he was very, very badly burnt. They took him to a Catholic hospital run by a brotherhood. He did not receive good care…

EM: Because…

SW: Because he was queer. Now I couldn’t go and see him because women weren’t allowed to go into the hospital whatsoever, but the men did. But they weren’t even changing his dressings. And even then we knew enough to use salt water dressings. If you can’t do anything else, you put dressings on and keep them saturated in salt water to keep them wet. They weren’t even doing that. They’d just let them dry and then seepage was coming through and…

So we moved heaven and earth to try and get him transferred out of there to a veterans’ hospital. And we got him moved the day before he died.

EM: That must have made you furious.

SW: That’s right. In fact, I’ve spent a large percent of my life being angry.

Barney, his name was. Barney.

EM: I guess that shocks me. It didn’t occur to me that such a thing happened before AIDS.

SW: Oh, yes. The hatred of the gay has existed as long as we’ve existed.

EM: But not to care for somebody who’s sick.

SW: That’s right.

EM: Didn’t that go against everything you were ever taught?

SW: Right. And of all people, those who pretended to be religious… I can’t say any more.

EM: Tape one, side two.

Uh, this upsets you a lot.

SW: Uh, huh.

EM: Still.

SW: Always will.

EM: How many years ago was this?

SW: This was about ’47.

EM: That’s more than 40 years ago.

SW: That’s right.

EM: Why is it…? What… What is it about that experience that was… that was and is still so upsetting?

SW: The…

EM: Here you go… a tissue.

SW: I think anybody who calls themselves an American, who believes in any kind of religion, to deliberately allow someone to die or force them into a position where they’re going to die, it’s unforgivable.

EM: So they killed Barney.

SW: They killed Barney. Because he was gay. He was another one of “those.” It was as though they did it to a brother or a sister or a close relative. He was a close relative.

EM: He was somebody you loved.

SW: He was one of my brothers.

EM: Was he a young man?

SW: I would say he was about 24.

EM: He was a baby.

SW: Yes.

EM: They killed a kid.

SW: Yeah.

EM: That’s incredible.

SW: I think this probably had a great deal to do with my aggressiveness. I had done it very privately prior to that time, you know, trying to set something up where we could have an ongoing group that would meet and have meetings and try to accomplish something. I had no specific goals in mind then. But after Barney’s death, I think, many of us became much more aggressive. We had to stand up and be counted. We had to make an impression somehow.

EM: Why?

SW: You couldn’t let that go on. That had to stop.

———

EM Narration: From the turning point of Barney’s death in 1947, fast forward to the 1960s. By then Shirley Willer’s work with the Daughters of Bilitis was taking her on the road from Boston to Texas and a dozen places in between. She was a lesbian Johnny Appleseed, starting new chapters of DOB and a few chapters of the Mattachine Society, another homophile organization, wherever she went.

Shirley Willer died from heart failure on December 31, 1991. She was 69.

Shirley found a way to channel her anger. One of the challenges I’m finding now is what to do with mine—over the gross incompetence of the people who should be leading instead of blaming, the systemic racism and economic inequalities that are fueling the deaths of the most vulnerable among us, and the bald-faced lies that got us to this terrible moment in the first place.

For the past three weeks I’ve been publishing a hyper-local neighborhood newsletter and I’m working on this podcast. But I’m often left feeling like I’m not doing my part, not making enough of a difference during this crisis. I think we can all feel pretty small in the face of a global pandemic that’s leading to so much suffering.

But then I get an email like the one I got yesterday from Cayden. Here’s part of what he said:

To all who read this,

I cannot thank Eric Marcus and the team who create this podcast enough, for allowing me to hope as we all navigate a world with new boundaries and requirements. I am a young gay college student, and I am presently living at home with my parents: my mom who is unwilling to accept my identity, and my dad taking a sharper turn towards hard religion. My dad in the last week has told me he would be content with me never speaking to him again. My mom encourages me to at least try hooking up with women. They have told me my identity is invalid, despite every fiber of my being knowing they are wrong.

Thank you for your podcast, as it allows me twenty-minute escapes each day. Every episode gives me hope that I can overcome my own struggles, and make a positive impact on my community at present and in the future. I smile, I cry, I laugh, each episode grounding me to a world that has otherwise left me untethered.

Thanks, Cayden, for your email and your supportive words, which encourage all of us at Making Gay History to keep doing what we’re doing. And to keep trying to make connections through history and across great distances in this time of physical isolation… You’re not alone, and your note helped us feel less alone.

And thank you to our listeners who have recently made donations to support Making Gay History, so we can continue sharing these stories with people like Cayden and our many thousands of other listeners around the world. I know that many people are struggling financially, so I’m especially grateful to donors like Louis Poulain, who is 71 and came out just five years ago. Louis, I admire both you and Cayden for your courage and perseverance in a world that to this day can be a hostile one for people like us.

Many thanks to all my colleagues who produce this podcast. A special thanks to Sara Burningham, our founding editor and producer, for producing this episode, and Inge De Taeye, Making Gay History’s deputy director for handling all the post-production work to get our episodes out to you.

So long. Stay safe. Until next time.

###