Revisiting the Archive — Wendell Sayers

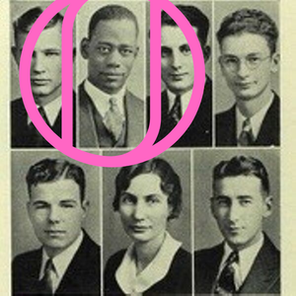

Freshman photo of Wendell Sayers, second from top left, in the Washburn College yearbook, School of Law, The Kaw (Topeka, KS: Washburn College, 1904–1933: 55). Credit: Ancestry.com.

Freshman photo of Wendell Sayers, second from top left, in the Washburn College yearbook, School of Law, The Kaw (Topeka, KS: Washburn College, 1904–1933: 55). Credit: Ancestry.com.Episode Notes

Wendell Sayers understood isolation. Born in western Kansas in 1904, Wendell was the first Black lawyer to work for Colorado’s attorney general; living openly as a gay man wasn’t an option. When he attended meetings of the Mattachine Society in the 1950s, his race set him apart. Yet, Wendell created a world for himself where he found purpose and meaning.

Visit our season one episode webpage for background information, archival photos, and other resources.

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

I’m recording this introduction on Thursday, April 2, 2020, exactly three weeks since my partner Barney and I began sheltering in place at our apartment on the west side of Manhattan, where it’s very, very quiet. Some of my neighbors have left town and just about everyone else is staying close to home. We know from the terrifying news reports that it’s anything but quiet at the city’s hospitals. At my brother’s hospital in Maryland, my brother tells me they’re getting ready for what they fear is a wave of very sick patients.

We’ve been hearing from friends across the country and around the world who are staying home or working on the front lines to keep the lights on or to save lives—in Kenya, Rwanda, the UK, Russia, Mexico, Denmark, Italy, Australia, and the little island of St. Bart’s. As scary, sad, and enraging as these times are, there’s comfort in knowing that we’re not alone.

And that’s got me thinking about Wendell Sayers. Wendell lived in a different kind of isolation. One that’s familiar to me because for the first 17 years of my life I never shared with a single person who I really was. But Wendell’s experience was also totally different, because I had the privilege of growing up in a world and at a time where I could later escape that isolation and live openly as a gay person—a world that’s grown ever more accepting since I came out in 1976.

Our listeners first met Wendell in our second ever episode, what feels like several lifetimes ago, in the fall of 2016. At the time we posted the episode, we didn’t know much more about Wendell than what he shared with me in his 1989 interview—beyond his birth in 1904, his harrowing growing up experiences, and the fact that he was the first African American lawyer to work for Colorado’s attorney general. I didn’t even have a photograph of him. The episode image we used was a beautiful sketch by artist Richie Pope that he created from my description of what I remembered of Wendell. Since then we’ve managed to uncover much more about Wendell and his life, and we’ve found a photograph, too. I’ll tell you all about it later in this episode, but first I want you to hear his voice.

I hadn’t planned on interviewing Wendell. I went to Denver in early 1989 to speak with Elver Barker, who had been active in the Mattachine Society, an early gay organization. When Elver told me a little about Wendell and his story, I knew I had to meet him.

So I headed to Wendell’s tidy one-story ranch, where he lived alone just a few blocks away from the old Stapleton Airport. Wendell was 84 years old, which you’d never have known from how sure-footed he was as he guided me through his house and into his dining room. He took a seat while I set up my recording equipment on the dining room table. Wendell was dressed for work, in a pressed white shirt, crisp gray slacks, a gray striped tie, and polished black shoes. I was eager to step back in time with him, so I clipped my microphone to his shirt and pressed record.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Wendell Sayers, Saturday, January 14, 1989. Location is the home of Wendell Sayers in Denver, Colorado. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Wendell Sayers: I grew up in a very segregated society, which kept me always aware that I was different. If anything went wrong in the town, it was always I who did it.

EM: That’s a lot of pressure.

WS: It’s a lot of pressure. And, uh, gradually I discovered that I was different, and I thought I was the only one in the world.

I remember one time when I first discovered that things were not right, I mean sexually, that I wanted to kill myself.

EM: Do you remember how old you were?

WS: I’d say about 15 then.

EM: Do you remember what you thought, how you realized you were different?

WS: Well, I knew I didn’t care anything about girls. Everybody else was chasing after girls and I couldn’t figure out why. Just didn’t make sense to me and still doesn’t. So…

EM: So you thought about killing yourself.

WS: I thought one time I just didn’t want to go through life this way. And I didn’t know any other way to keep from it. And I was just completely down and out, so to speak. I gave up, practically.

Finally, my dad come to me one day and told me what he had heard. Whether he heard it or how he found it out, somebody must have told him.

EM: What did your dad hear?

WS: He didn’t tell me. He told me things, he told me that he had heard that I was not natural, sexually. He said, “We’ll go up to Mayo Clinic, get your examinations, and see if we can find out what causes it, what to do about it.” So he puts Mother and I in the car and we go up to Minnesota. That was back in the days when you couldn’t get a place to stay, couldn’t get a place to eat.

EM: Because you’re Black.

WS: Because you’re Black, see.

EM: What did you do?

WS: Buy crackers and bologna in the store and take ’em out and eat ’em. Stuff like that.

EM: Where did you sleep?

WS: Got a tent. We got one of these 10-by-12 tents and we stayed in the tent at night. Take all of that and put it together, it’s awfully hard on anybody, I don’t care if he’s white or Black or green or yellow.

EM: Right.

WS: That kind of pressure is terrific.

EM: How old were you then?

WS: I was still quite young.

EM: Were you still in high school?

WS: Yes, I think I was still in high school.

EM: You must have been terrified.

WS: I was terrified. They had me in the hospital for… in and out for several days.

EM: Did they ask you questions?

WS: Oh, yes. All kinds of questions. They determined that I was homosexual and that there was nothing they could do about it. And final report from Mayo’s was that, according to their state laws, that I should be, they should report me and have me incarcerated.

EM: Incarcerated?

WS: Yah.

EM: For what?

WS: Because I was different.

EM: Put in jail?

WS: In jail. They said that since I was a client of theirs they would not do that. So we went back home and reported to Dad. I might say this, that I was an adopted child. And I often used to wonder as a kid, what will he do when he finds it out, see? Will he put me out or kick me out? Or will he accept me?

My dad was very understanding. I say understanding—I don’t think he actually understood—but he was willing to accept, I should say. So he finally told me, he says, “Well, since they don’t know what to do about it, find you a friend that you can trust. And bring him home. I don’t want you playing around on the streets or out on the country roads ’cause you never know who’s going to step up behind you, step up on you. Bring him home. What you do in your room is your business.” Because he didn’t want me out on the street.

That helped me a lot. At least I was loved by my father. And, of course, Mother, she just idolized me, regardless. They were remarkable people, as I look back. I didn’t think so at the time.

EM: No one thinks his parents are remarkable at the time.

WS: But as I look back, I can certainly appreciate them.

EM: Yeah.

WS: Ask me something.

EM: Okay. There were no organized gay groups when you were first here in Denver.

WS: Mattachine was the first organized group, I think, as far as I know of. And I had a friend that worked down at the depot.

EM: The depot? What kind of…?

WS: The train depot. It’s where the train used to come in. And he was gay. And he asked me—he was going to the meeting one night and asked me if I’d like to go along. I said, “Yes, I’ll go.” So we went into somebody’s home I didn’t know. I went in. There was a group of guys sitting there—I imagine 10 or 12 maybe?

I went first place, I’d say, to know or to meet somebody who was like me. I mean gay by that. That was my primary purpose in going. It developed later, or as time went on, that once I found there were others besides me I was much better able to accept myself.

EM: Can you elaborate on that at all, what you mean by that?

WS: Well, you see, to me I was always a thorn in the flesh to me because I was gay.

EM: You were your own thorn.

WS: I was my own thorn. And this, uh, talking about it and going over experiences together helped me to realize, well, maybe I’m not the only one.

EM: Were you scared?

WS: No, I had nothing to be scared about. No, I think I scared them worse than they scared me.

EM: Why did you scare them?

WS: Well, I was the only Black one.

EM: Oh, and they probably weren’t accustomed to having any contact with Blacks.

WS: They weren’t accustomed to having any contacts with Blacks. So I come in and for once I found somebody else besides me that would say they were gay, see.

EM: Up until that time no one had said…?

WS: I knew a few.

EM: Right.

WS: But, I mean, but to have a group—I had never been in that sort of situation before, see. I was completely happy to find somebody because I thought I would be accepted and a part of the crowd. And I was really happy the first meeting I went to. The guys were not friendly.

EM: They weren’t friendly.

WS: But that was alright. They didn’t know me. All they knew was I was a lawyer and they were afraid of me, I think, because I was a lawyer. They were terrified of the law. “What’s this guy doing here? Who’s he going to turn in?”

EM: Were you concerned about your practice when you went to this first meeting?

WS: I was concerned about my practice at every meeting I ever went to because I was working for the attorney general’s office at the time.

EM: Oh, you must have been really concerned.

WS: First Black ever up there.

EM: First Black to work for the attorney general.

WS: Yeah.

EM: In Denver.

WS: Had my office right there in the capitol building. So every time I went to Mattachine, I was as scared as the rest of them, only I wasn’t scared of the same thing as they was, see?

Just imagine the Denver Post would come out, front page, “First Black in the attorney general’s office turns out to be…”

EM: Could throw yourself off the capitol for that one.

WS: I sure would. I’d been raised so much as an underdog, I just would have done anything if I could have taken a step higher, see? Regardless of my gayness, I was still somebody.

EM: Did they ever ask you legal questions?

WS: They would ask me… Sometimes I’d volunteer. They’d talk about something. Once in a while I’d volunteer a little legal information. But to be… I was not a hired or paid consultant, just a volunteer. Everything was volunteer back in those days.

I remember one time, I set up a… One boy had got himself caught with a whole lot of nude pictures. And of course they took him down to trial. And beforehand, why, I don’t know whether he asked me or the society asked me or what, but anyhow, I knew the judge. The judge happened to be gay and I happened to know him. So I went down and thought I had made arrangements with the judge to when this case comes up…

EM: You were gutsy. You were nuts!

WS: Plumb nuts. As I look back now I was plumb nuts, I can’t deny it. I went down and asked the judge, talked to him personally. I told him this guy was coming in and I wished he’d be as lenient on him as he could. And, damn it, excuse me, when it come time for the trial, the judge took that day off.

EM: He didn’t want anything to do with it.

WS: He didn’t want anything to do with it. But I was kind of glad afterwards that I had warned him ahead of time. Because he and I were good friends, see? Nothing between us, but just good friends. And I think he knew me and I think I knew him. So he just took that day off when that guy was coming.

EM: So you advised on a number of cases like that then?

WS: That’s the only one.

EM: The only one.

WS: I think that was the only one.

EM: But you stuck your neck out. That was way out.

WS: That was way out. It’s a wonder somebody didn’t chop it off. It’s a wonder somebody didn’t chop it off.

EM: You must feel like God’s been watching over you pretty carefully.

WS: God’s watched over me, I’m telling you, ever since the day I was born. Yes, sir. Definitely.

———

EM Narration: Wendell Sayers died on March 27, 1998, just shy of his 94th birthday.

Since we first shared Wendell’s episode, we’ve learned a lot more about his life thanks to Michael LeClerc, a genealogist we hired to scour for information on Wendell Sayers.

We learned that Wendell was born in Nicodemus, Kansas—a town created after the Civil War for ex-slaves. Wendell’s grandparents were all former slaves.

Wendell was the adopted son of William Sayers and Sarah Bates. William and Sarah both came from large families; each had nine siblings. Wendell’s birth parents were William’s older brother George and Sarah’s older sister Mary, who had eight children. William and Sarah had been married for almost 10 years without having children of their own; George and Mary gave their youngest son, Wendell, to their childless siblings.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Wendell attended Washburn College in Topeka, Kansas, where he later got a law degree.

Wendell’s mother was an active member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and other organizations. When his father died in 1956, he left an estate of $115,000, the equivalent of more than a million dollars today. Part of the estate was to be used to help African Americans find places to get food and lodging without being rejected because of their race.

In 1945 Wendell started his private law practice in Denver. He worked on many civil rights and discrimination cases. In the 1960s he became the first Black assistant attorney general for the state of Colorado.

After retiring, Wendell returned to school to get a bachelor’s degree in music performance and theory from the University of Denver—music was his first love. He appeared in multiple volumes of Who’s Who in Black America.

I’ve often thought of the last words Wendell said to me as I said goodbye to him on the steps of his house more than 30 years ago. “Is it too late,” he asked, “for me to meet someone?” That question has always left me with a heavy heart, because it suggested a lifetime of isolation and loneliness—an isolation that was forced on Wendell by a world that would have destroyed him if he hadn’t hidden his sexuality. And later, a self-imposed isolation in a changed world that Wendell didn’t yet trust would accept him.

But in these difficult times, when isolation is a necessity for so many of us, I also think of Wendell as an inspiration. Wendell created a world for himself. He persevered. He bore his alone-ness with dignity and resourcefulness. He found community in his church. He pursued his love of music and proudly showed me the gleaming electric organ that took center stage in his living room. He found ways to cope, found meaning, connection, and pleasure under trying circumstances. I hope the same is true for you.

Thanks for listening. And thank you to our listeners who have recently made donations to support Making Gay History, so we can continue bringing LGBTQ history to life through the voices of the people who lived it. I know that many people are struggling financially and aren’t sure how they’ll pay their bills, so I’m especially grateful to donors like Bob Brager.

Bob lives in Amsterdam and made a donation in honor of his late partner, Jay Manning, who died from complications of AIDS in their apartment in New York City at the height of that epidemic. Bob wrote, “As soon as I heard your podcast, I knew that Jay would want me to contribute to it. So it was a welcome impulse. Truly in memory of him. I’m very grateful for your fine work. I remember the bad old days, and I know how indebted we are to the people you interviewed. Thank you for keeping their stories alive.” Thank you, Bob. And I’m so sorry about Jay.

Many thanks to all my colleagues who produce this podcast. A special thanks to Sara Burningham, our founding editor and producer, for producing this episode, and Inge De Taeye, Making Gay History’s deputy director, for handling all the post-production work to get our episodes out to you.

So long. Stay safe. Until next time.

###