Revisiting the Archive — Larry Kramer

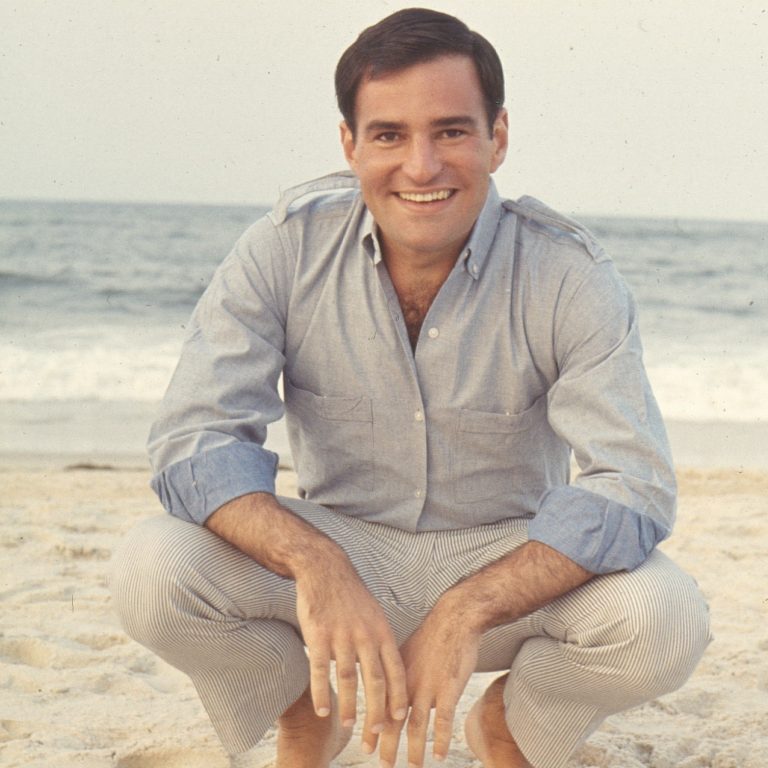

Larry Kramer, 1978. Photo courtesy of Larry Kramer Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Larry Kramer, 1978. Photo courtesy of Larry Kramer Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.Episode Notes

June 25, 1935 – May 27, 2020. In the early ’80s, author and playwright Larry Kramer was one of the first people to sound the alarm about AIDS. He became one of the loudest voices in the fight against the epidemic, calling an indifferent world to account.

Visit our season three episode webpage for background information, archival photos, and other resources.

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History. It’s now been 11 weeks since my partner Barney and I began sheltering in place. And this past week the official death toll in the United States from Covid-19 rose past 100,000—mothers and fathers, children, grandparents, colleagues, neighbors, and friends. People. Not numbers. People.

I’ve talked before in this series “Revisiting the Archive” about anger—how it can fuel action, how when anger is partnered with love it can produce a kind of righteous rage that propels us. Those of us who lived through the AIDS crisis know about it. Some of us learned it from Larry Kramer, who died this week, in Manhattan, where he’s lived for decades. Larry was famous for being one of the first civilians to sound the alarm during that last epidemic, the one that began 40 years ago. He was on the front lines even before AIDS was called AIDS and became a global epidemic that’s swept away more than 30 million lives.

Before AIDS, Larry was best known for his work as a screenwriter and author. But the virus that was claiming so many lives and the political indifference—political negligence—that greeted it turned Larry into a very public activist. His friends were dying. And he felt compelled to do something more than to just bury the dead and mourn their loss.

In 1982 Larry co-founded the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, now known as GMHC. Five years later he co-founded ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. ACT UP came to be known for its brilliant use of public protests to bring attention to the epidemic. By early 1989, when I first met Larry, AIDS had taken more than 60,000 lives, most of them gay men.

Larry quickly earned a reputation as an uncompromising firebrand with a fierce temper. I’m not proud of it, but that kind of person generally inspires me to run in the other direction. I was more than a little anxious as I approached the door to Larry’s apartment in a building that fronts Washington Square Park in New York City’s Greenwich Village. As I said when this episode originally aired, I got myself worked up for nothing. I had braced myself for a tornado and found a teddy bear.

Here’s the scene. Larry welcomed me into his spacious apartment and showed me into his all-white, book-lined living room, and I took a seat opposite him across a broad desk. As I set up my tape recorder and attached the mic to his shirt, we talked about how we both had wanted to find a husband early in life and settle down. And that led us back in time to Larry’s memories as a confused and unhappy college student in the early 1950s. I pressed record.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Larry Kramer, Thursday, January 26, 1989, at the home of Larry Kramer in New York City. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Larry Kramer: When I went to Yale, I thought I was the only gay person in the world, and tried to kill myself because it was so lonely.

EM: Actually did try to kill yourself?

LK: Yeah.

EM: What year was that, that you…

LK: And I think that was ’53 was the year, my freshman year at Yale. Oh, it was awful. I mean I—do you want to go back that far?

EM: Well, I’m also curious, because I was a college student in ’76, desperately unhappy.

LK: Where?

EM: At Vassar College.

LK: Where there were a lot of gays.

EM: There weren’t that many. People think there were a lot. I always said, if there were so many gays, why was I so unhappy? But I was a miserably unhappy person, and death seemed very appealing at moments during my freshman year, when I was dating a woman and sneaking off with a man behind… And life in ’53 at Yale must have been much more difficult than ’76 at Vassar.

LK: Well, I don’t know if you could even start in ’53. I knew I was gay, I think, from the day I was born. And I think there have been—I now know that there were experiences all through, before I even got to Yale, and they were all covert and guilt-inducing on everybody’s part.

So it seemed as if all those early years were spent trying to deny these feelings. The feelings would sort of get too strong and erupt, and I would have an experience which would always make me feel guilty in one way or another, and then you’d put it—you’d be calm, Vesuvius would calm down for a while.

EM: A week.

LK: A week or two. And Yale was awful. There was a gay bar called Pirelli’s. It was just awful, when I finally had the courage to go there. It was only two blocks from campus. But it was a million years away. It was very dark and gray inside, and smoky, and filled with older men, and I only went the once. And somebody picked me up in a car and drove for what seemed like hours before we found a place that was quiet, to do it, and then he drove me back, where you didn’t say a word, all of that.

EM: How did you try to kill yourself?

LK: I ate 200 aspirin.

EM: Oh, my god, talk about slow and miserable death. You must have been pretty miserable to swallow 200—and you must have been even more miserable after. Did you just, you wanted out? Was that…?

LK: Who knows? It’s a scene I’ll never forget.

EM: The scene of taking the pills? Or the scene of waking up and finding you’re still there?

LK: I didn’t wake up. I went to bed and I got scared and I called the campus police, and they came and took me to the hospital and pumped my stomach. And I was in a—then I fell asleep and I woke up in a room with bars. And… at the Grace New Haven Hospital, and it was this very unpleasant hospital psychiatrist who said, “Alright, Mr. Kramer, why did you do it?” And I said, “Go fuck yourself,” or words to that…

And he said, “You’re not going to be let out of this hospital until you tell us why you did it.” And I said, you know, I just had a—he rubbed me the wrong way, and I wouldn’t have told him. Who knew why I did it, anyway?

So my brother, who’s always sort of looked after me, came and got me out, and he was friends with the dean of freshman. My brother had been to Yale before me. And it was, you know, ordinarily when something like that happened, you were shipped off to go join the Army.

EM: Really?

LK: In those days, yeah. And then you’d come back to Yale when you’d sort of grown up. But they let me stay if I went to the university psychiatrist. His name was Dr. Fry, Clement Fry, and he was about, in his 60s. He had silver hair, and he was a good-looking man, he wore his rep tie and his button-down shirt. And you just knew that he cared more about Yale than he ever did about you.

And I told him of this experience that I had had of—I had been invited to go to the room of two of my freshman year, two guys freshman year that I had met. And they somehow mercifully had found each other, and they were living in this room, and I was invited for tea or something. And I walked into this room and the room—you know how awful freshman year rooms are—well, they had done their room, and it was painted all black. And there was, everything had been taken out of the room except, you know, a low mattress, which was black, and there was a perfect coffee table with a rose in a vase, that was spotlit, and…

EM: Gay men are born…

LK: And Mabel Mercer is playing on the phonograph, right? So I described this all to Dr. Fry, and Dr. Fry’s reaction was, “I wouldn’t see those guys anymore if I were you.” And that’s what Yale was like, and that’s what going to a psychiatrist was like, so…

EM: And there wasn’t, there wasn’t a local gay student group for you to call.

LK: There was not, I mean, I love going back to Yale now, and this is my real yardstick of how far we’ve come, even though I’m always yelling about how we’ve not come far enough. I go back to Yale and Yale is like the gay college now. And there’s a dance every year for, you know, well over a thousand gay men and women, you know, across the campus from where I tried to kill myself because I thought I was the only one.

EM: So that is your yardstick for change.

LK: It certainly is, yeah.

EM: That in 30 years’ time… You were completely alone.

LK: Thirty years it is. God. It’s a long time. So, where does that leave us? A lot of change and no change.

EM: Well, yeah.

LK: Well, I guess, it’s in my nature to be impatient. And I only got politically involved because of AIDS. And there’s no question that we have lost the war to AIDS, and that we have lost and will continue to lose a great many people whom we did not have to lose, and that the speed of research, treatment, education, you name it, has been tragically and inhumanely slow. It’s an epidemic that need not have happened. And that we should have listened. There’s no question that enough people knew what was happening.

EM: Who should have listened? Are there people specifically who should have listened?

LK: Well, the community. I mean, the gay press, the gay leaders.

EM: You were there before it was an epidemic, or just as it was becoming…

LK: Well, I think now we know that even when we found out in ’81, it was much bigger than we thought, but we thought it was just beginning. Right. ’81, in this very room, in August ’81, 80 men sat with Dr. Friedman-Kien from NYU, who told us, in no uncertain terms, exactly what was happening. And, uh, and he was right.

EM: In ’81.

LK: In August of ’81. The New York Times article that alerted everybody, really, was July 3, ’81. The New York Times headline was something like, “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” and it said that all the guys had the same history, which was the history of having had all of these sexual diseases: amoebas, hepatitis A and B, and mononucleosis, and syphilis, and gonorrhea, and you name it.

When I saw that in the New York Times, I was scared. Because I’d had all of that, and I guess a penny dropped, as the English say, or the bell rang, or something. And I called Larry Mass, who was and is my friend, who is a doctor and who had written some articles. He wrote a health column for the Native, and had written about it before the Times had. And I guess I’d spoken to him peripherally about it, but not—it had, the bell hadn’t rung, I guess, until the Times—the Times has a way of making you really sit up and say wow.

EM: Well, if the Times covers it, it has to be real.

LK: So he said, “Go talk to Alvin, to Dr. Friedman-Kien,” which I did. And Alvin, who turned out to be gay, and we turned out to have mutual friends, said, “This is what’s happening, you gotta stop fucking. You’re someone well-known in the gay community. You have to do something about it. Somebody’s gotta go out there and tell them.” And it was because of that, that I invited Larry Mass and I and two other guys now dead, Donald Krintzman and Paul Rappaport, invited everyone we knew to come to this first meeting in August.

EM: Did that include people from political groups, gay political groups?

LK: We got on the phone and we called everybody. We called anyone we could think of. Political people, rich people, media people, doctors—none of whom showed up—and it was a good cross-section. And it was, you know, a lot of people didn’t believe ’em.

EM: Did you know this was a hot political football when you picked it up? Or did you expect people would respond to you, or to what you had to say?

LK: You know, that very meeting that night, with—it was in the early evening, with Alvin, so that, I mean, there were a lot of very nasty questions put to him. There were a lot of people saying, you know, you’re a born-again. How can you make all of these assumptions on the basis of so few cases? And how can you expect the whole community to stop fucking? And, you know, there was no virus then. I mean, people say there’s no virus now, but there certainly was no virus then, and that didn’t come for another couple of years, and people could say, “You have no evidence to base this on.”

EM: But didn’t anyone say, even if there’s the slightest possibility?

LK: Well, that’s what he was saying and that’s what I was saying. And it wasn’t so much the people that Paul Popham and Nathan Fain, who came to be my big adversaries in Gay Men’s Health Crisis… It wasn’t so much that they didn’t believe or not believe what was happening. Paul had of course lost a couple of friends by then, and a lover. It was that he didn’t think it was GMHC’s, or anybody’s position to tell anybody else how to live their lives, and that people had to make up their own minds.

And so a lot of valuable time was lost not being the conduit. I thought I was setting up or fighting to help set up with others, an organization that was going to do one thing, and that organization became, and still is another.

EM: What was it…?

LK: It was set up to spread information and to fight. To fight to make the system accountable and to spread the word of what was happening, and that, you know, we gotta cool it. It was not that at all. It became very quickly—it was taken over by the social workers, and it is now what it is then, it’s a social service, and a very good social service organization.

But it, again, that’s our tragedy. It’s an organization that helps people to die, it is not an organization that helps the living go on living. And we still don’t have an organization to do that. You know, except maybe ACT UP, which came along much too late. Better late than never, but much too late.

I blame myself. I am very cognizant of a great failing on my part that I did not have the ability to be a leader, that I did not have the ability to deal with my adversaries and still be friends. God didn’t, if there is a God, did not give the gay community a leader when the gay community needed a leader. And it still hasn’t.

EM: And you failed in that role.

LK: And I failed in that role. I feel very strongly, I failed in that role.

EM: What does the future hold, then?

LK: I think AIDS is going to get much, much worse and a lot more people are going to die, and I hope that one of these drugs is going to do something about it, but… I never seem to hear of any letup in the number of people who seem to be getting sick, and that’s very scary. And I’m HIV-positive myself, which I’ve just discovered and, uh…

EM: You just were tested. For the first time?

LK: For the first time, yeah. And I… you know, for the first time it’s come home to me in an even more personal way that my days may be numbered, in a way that I didn’t think of before. And that’s made me real sad, more than angry.

I find myself going back to ACT UP, which I haven’t done in a long time, because I got fed up with it.

EM: Well, there must be a renewed personal… There’s a greater personal interest than before, I would think.

LK: Their fighting takes me out of my negativity. Makes me, just sort of being touched by their positivism helps me.

EM: There are a lot of things I haven’t asked you. Is there anything that you would like to comment on…

LK: I don’t feel like I’ve been at my best today with you.

EM: I’ll come back.

LK: I feel a little specious in what—not specious. I feel a little…

EM: Scattered?

LK: Buck scattered in what I’ve said. So I don’t know if I’ve said what I’ve… I love being gay. And if I have been, and am critical, it’s only because I think we are very special people and capable of so much more. And it’s taken me a long time to be able to say that, because I’m of a different generation than many, you know…

EM: You were born what year?

LK: ’35. And I’m the generation that was sent off to shrinks because shrinks then thought they could change you, and you were expected to change. And it took a long time for me to come to terms with my homosexuality, and a lot of shrinks. Now, having come to terms with it, and liking it, and then having to face AIDS, is almost like a bum rap. Nevertheless, it’s… You know, I think we are very lucky.

I just, I think being a gay man, even today, with AIDS, is a wonderful thing. I love being gay.

———

EM Narration: After I turned off my tape recorder, we talked about Larry’s health. Besides being HIV-positive, two-thirds of his liver had been destroyed by the hepatitis B virus. His doctor had told him that he had maybe three years to live. So legacy was very much on Larry’s mind. He told me that he saw his work as his legacy. But at the risk of disagreeing with Larry—not that he’s here to argue with me—I think his biggest legacy was saving lives through the activism he inspired and his warnings about AIDS, which were heard by more than a few of us, including me. A lot of us owe our lives to Larry Kramer.

Larry outlived his doctor’s prognosis by several decades. Experimental drugs and a liver transplant in 2001 saved his life. Larry also got his wish to find a husband, settling down with David Webster in 1991. They married on July 24, 2013. Larry Kramer died this past Wednesday, May 27, 2020. He was 84.

Actually, there’s another memory of Larry I’d like to share before I go. I visited with Larry one more time after that 1989 interview. It was at lunch the following summer with my mother in the Hamptons on eastern Long Island where Larry was renting a house. They were both in their 50s—younger than I am now. I have no memory of how that lunch came about or how my mother came to be a part of it. I’m guessing she asked—and she was known to be insistent. But what I remember clearly is how much they enjoyed each other’s company. Two Jews of a generation that spawned so many fighters for social justice—my mother included. They spoke the same language and I had the privilege to sit back and listen. How lucky was I… I don’t believe in heaven, but I like to think of the two of them meeting up for lunch again, looking down on us, wondering how we’ve made such a fucking mess of things—and urging us to fight for our lives and the future of our country.

Many thanks to the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation for their ongoing support. If you’d like to join us in our mission to bring LGBTQ history to life in the voices of the people who lived it, please go to makinggayhistory.org/support or visit our website at makinggayhistory.com.

This “Revisiting the Archive” episode was produced by Sara Burningham, Making Gay History’s founding editor and producer, and Inge De Taeye, Making Gay History’s deputy director, who handles all the post-production work to get our episodes out to you.

So long. Stay safe. Until next time.

###