Reed Erickson

Reed Erickson (center) with girlfriend Daisy Harriman (left) and Michele, 1963.

Credit: Photo courtesy of the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Reed Erickson (center) with girlfriend Daisy Harriman (left) and Michele, 1963.

Credit: Photo courtesy of the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: When I interviewed ONE magazine newshound and intrepid archivist Jim Kepner back in the summer of 1989, he mentioned in passing a person named Reed Erickson. I paid so little attention to that name that I didn’t recall ever hearing it until MGH‘s executive producer Sara Burningham told me about Reed’s central role in the 1960s gay and trans rights movement as we were planning the episode lineup for season four.

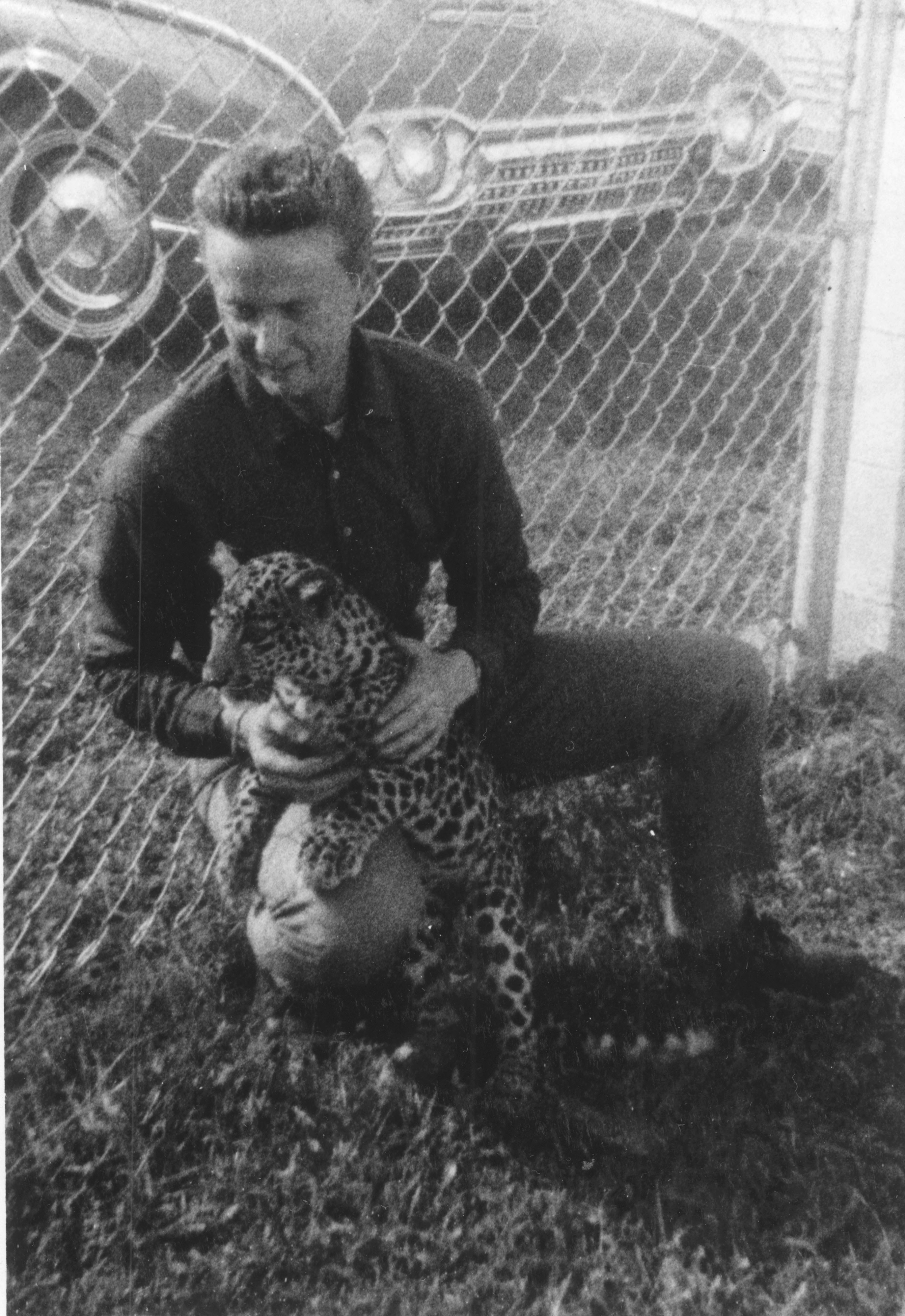

Reed Erickson was a trans man with a big checkbook and a pet leopard named Henry. Turns out that beginning in the early 1960s, Reed was the money behind the organization that published ONE: ONE, Inc. With Reed’s very generous support, ONE, Inc. went on to do all sorts of pioneering things, including offering classes in homophile studies—queer studies long before there was queer studies.

Reed Erickson also launched the first trans rights organization in the U.S. and funded work that was foundational in developing early trans healthcare protocols. But his interests didn’t end with gay and trans rights. Reed also funded research into a whole host of counter-cultural, New Age initiatives, including human-dolphin communication.

Because Reed was such a private person, he never gave a recorded interview—at least not one we could find—so we asked Reed Erickson experts Morgan M Page and AJ Lewis to join me for this episode to help bring Reed’s story to life. And there’s a lot to it, including a decade-long legal battle with ONE over ownership of a famous Los Angeles estate that wasn’t settled until after Reed died in self-imposed exile in Mexico. Like so much of the history we’ve explored, it’s complicated!

To learn more about Reed Erickson and our special guests, have a look at the archival photos, additional information, and episode transcript that follow below.

———

For a history of the transgender movement in the U.S., check out How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States by Joanne Meyerowitz and Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution by Susan Stryker.

For a biographical overview of Reed Erickson and an account of his contributions to the homophile and transgender movements, check out this essay by Ada Bello from OutHistory.org as well as this article by Dr. Aaron Devor and Nicholas Matte.

To explore some of the Erickson Educational Foundation’s publications and other Reed Erickson materials, visit the University of Victoria Transgender Archives Collection here.

The Milbank estate figures prominently in the story of ONE and Reed Erickson. Learn more about the Milbank mansion, which was built in 1913 in L.A.’s Country Club Park neighborhood, here and here. The mansion has served as the setting for numerous movies and television programs, including a reality TV show called Beauty and the Geek.

Read about Reed Erickson’s involvement with ONE Incorporated in this article by Dr. Aaron Devor and Nicholas Matte. Listen to our MGH episode on some of the key figures of ONE here.

Reed Erickson funded the work of pioneering endocrinologist and sexologist Dr. Harry Benjamin. Read Benjamin’s New York Times obituary here. Read his 1966 The Transsexual Phenomenon in its entirety here.

Morgan M Page’s One from the Vaults trans history podcast featured a special episode on Reed Erickson. You can listen to it here. Learn more about Morgan M Page and her work on her website. Watch her speak at SlutWalk Toronto 2012 here.

To find out more about AJ Lewis, listen to his testimony from the NYC Trans Oral History Project, a collaboration with the New York Public Library, here. Listen to other collected voices here.

In 2012 video maker and interdisciplinary artist Chris E. Vargas produced ONE for All, which is about the tempestuous end of the partnership between Reed Erickson and ONE. The story focuses on the Milbank estate and on the expansive, but unrealized, dreams that Erickson had for the future of queer activism. The video was part of Transactivation: Revealing Queer Histories in the Archive, an event staged at the ONE Archives. To learn more about Vargas’s work, check out his website. Find out more about his MOTHA (Museum of Trans Hirstory & Art) project here and on the website of the New Museum in New York City.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History!

As you’ve been hearing through the voices of this season of the show, the early LGBTQ civil rights organizations and activists faced all kinds of potentially devastating challenges, from internal conflicts over goals and tactics to FBI investigations and police entrapment. But there’s one challenge we haven’t explored yet. That’s money. Or, more precisely, lack of money.

Take ONE Incorporated, for example. Our last couple of episodes have focused on the people who in the early 1950s launched that organization’s first effort, ONE magazine. We shared with you their disagreements and infights, the court battle with the U.S. Post Office to send ONE magazine through the mail, and a landmark win in the U.S. Supreme Court. But you didn’t hear about their desperate finances. And you didn’t hear about the major benefactor who rode to their rescue, only to be erased later from their history.

So let’s pick up where we left off with ONE. Dorr Legg, ONE’s co-founder, had big ideas, but a shoestring budget that was stretched to the limit. Dorr dreamed of establishing a university-level degree program in homophile studies—a queer studies program before there were any queer studies programs.

By the 1960s, ONE had started the ONE Institute of Homophile Studies, was publishing an academic quarterly, and producing a series of lectures and workshops known as the ONE Mid-Winter and Summer Institutes. ONE was also providing information and legal advice. And the organization even made what I think of as a kind of proto-podcast—an audio history of the organization that they recorded on tape to send to their members. Have a listen.

———

Joe Aaron: How do you do? My name is Joe Aaron. I’m chairman of the board of directors of ONE Incorporated. At this time, I’d like to introduce Manuel boyFrank, secretary and treasurer of ONE Incorporated.

Manuel boyFrank: Two things seem to me of primary importance. They are money and love. I have been very much preoccupied with the money that ONE Incorporated needs and does not have. The other subject seems to me the polestar of our behavior. Probably no lawyer can predict what entanglements we are liable to get into nor what we should do beforehand to cope with them. Nor can any physician predict similarly what we should do about hygiene, particularly emotional hygiene. But in either of those concerns, we shall probably do fairly well if we are guided and impelled by love, genuine love.

———

EM Narration: That last voice you heard was Manuel boyFrank, sharing his thoughts on gay love back in 1963. But enough about love. Back to the money.

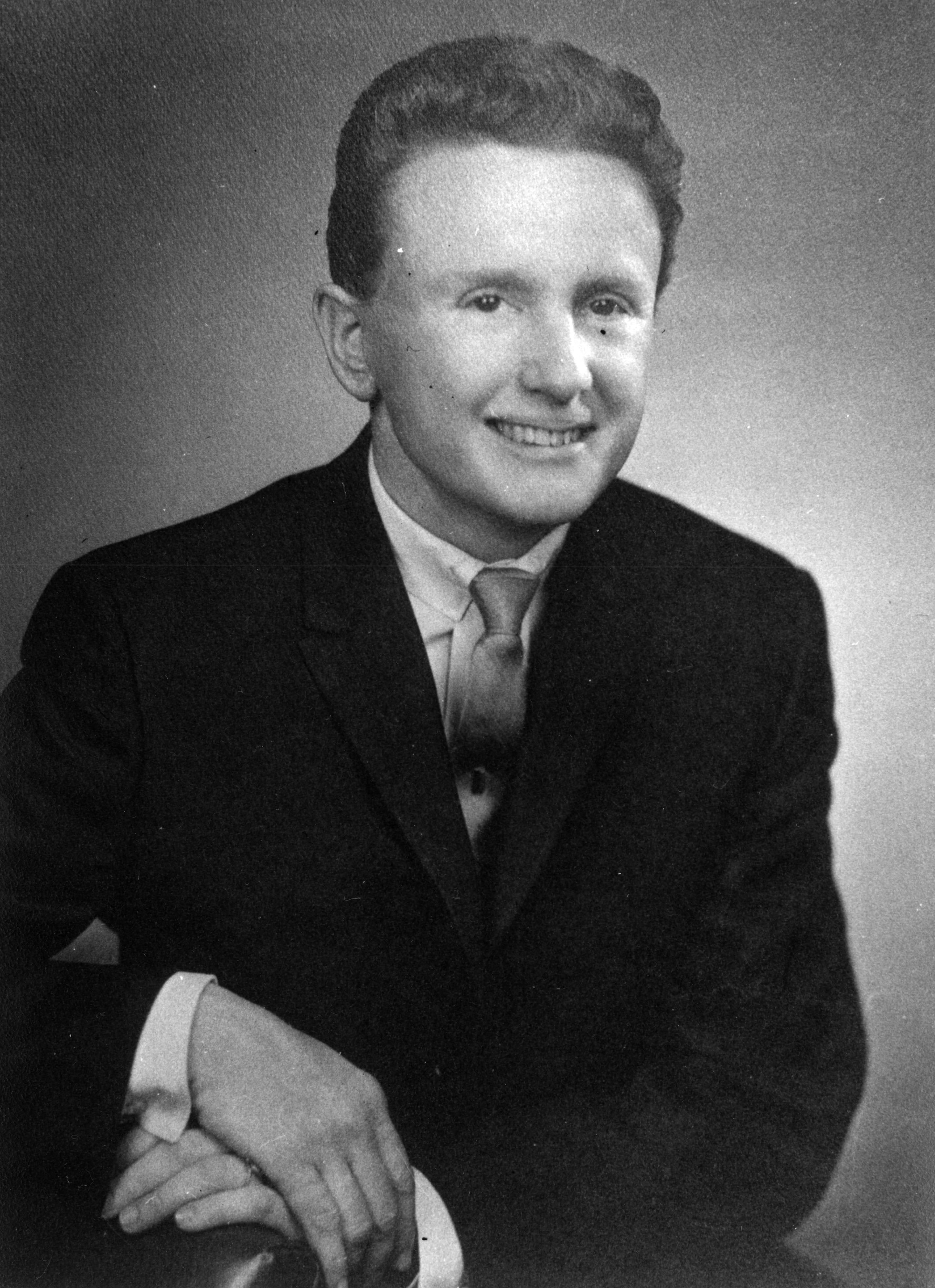

ONE was in a precarious position. It couldn’t pay its writers and struggled to pay all its other bills. ONE had lost its first office after an earthquake, and in 1962 it faced eviction again. The building on Venice Boulevard in Los Angeles where they had their new headquarters had been put up for sale. They sent out a desperate call for donations to buy the building. And a knight in shining armor appeared. In this case, the knight in shining armor was Reed Erickson—a trans man with a big checkbook.

Reed was a totally fascinating and eccentric person. As you’re going to hear, his name and influence was all over ONE Incorporated and early trans activism. But Reed was also an intensely private person, preferring to operate behind the scenes instead of speaking out publicly. So I’ve asked Morgan M Page and AJ Lewis to help guide me through Reed’s life and legacy.

Morgan Page is a writer, an artist, and host of the trans history podcast One from the Vaults—and you should definitely listen to her episode on Reed Erickson. Welcome to Making Gay History, Morgan.

Morgan M Page: Thank you for having me.

EM: And we’re also joined by AJ Lewis. AJ is a postdoctoral fellow at Grinnell College specializing in, among other things, queer and feminist theory, trans studies, and U.S. activist history. He’s also one of the founders of the NYC Trans Oral History Project and he’s working on a history of trans activism. Welcome, AJ.

AJ Lewis: Hi, thank you.

EM: Let’s start with how Dorr Legg and Reed Erickson met. ONE had sent out that appeal for donations and Reed got in touch. That was in 1962. Then, in 1964, Dorr and Reed met face to face for the first time. I’m going to play you some tape of Dorr Legg talking about that first meeting, which happened over the 4th of July weekend after Reed Erickson sent Dorr a plane ticket and asked him to come to see him in Louisiana.

———

Dorr Legg: I met Mr. Erickson, was put up very handsomely at a motel near the airport, and we talked practically all the first night and that was it. He just asked questions and said, “Well, call me when you’re up in the morning. We’ll have breakfast and we’ll keep talking.”

Into the second day of discussion, he said that “I’ve been watching the work of ONE Institute, I’ve been watching your Quarterly, I’m very much impressed. Do you have some projects you would like to have financed?” I said, “Do we have projects we’d like to have financed? Just tell us when.” So he said, “Well, go back to Los Angeles, talk to your people, and set up a schedule of what you want to do and how much it would cost.”

When I first met him, I thought it was a high school boy. I thought, Well, what on earth does this young kid invited me down here to talk about financing something? And I came back and was completely bopped over the head by the corporation members who were just sure that the heat had touched me on the weekend trip down there, because they couldn’t believe, the whole thing sounded so fantastic. It didn’t seem to make sense. However, every word has come out just precisely as he described it at the time.

———

EM: And thank you to the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries for that clip, which was recorded back in 1966 at ONE’s Mid-Winter Institute.

So that’s what Dorr Legg had to say about meeting Reed. What else do we know about that meeting? Morgan, can you start us off?

MP: Well, I do know that it made quite an impression on Dorr Legg in particular that people later did not believe him that he had met this essentially high school-looking teen boy who was wrestling with a leopard. It was a very odd meeting, but one that proved to be quite fruitful in terms of their future collaboration.

EM: And, yeah, I think when Reed mentioned Henry, Dorr assumed Henry was Reed’s lover. But that’s not who Henry was, right, Morgan?

MP: Reed Erickson had this pet leopard that he had had for a number of years and ended up keeping for the better part of 20 years. He was very attached to this leopard and even took him onto planes for business trips and just sort of was never without his pet leopard, Henry.

EM: And, Morgan, in your episode of One from the Vaults about Reed, you have a great way of characterizing him—what’s the phrase you use?

MP: Well, I like to refer to Reed Erickson as the trans Howard Hughes because he was a very wealthy and influential man who became progressively more, let’s say, eccentric over the years.

Reed Erickson was born into a fairly wealthy family, and he became a bit of a socialist and a communist until he transitioned, and following his transition in the early 1960s he started to become more and more eccentric. He started experimenting with psychedelic drugs, later becoming addicted to ketamine and cocaine, and he also, not only did he invest a lot of time and money in the early gay rights movement through the homophile organizations like ONE, but he also created some of the first trans advocacy organizations, including the Erickson Educational Foundation.

And in addition to all of those things, Reed Erickson was this short ginger with kind of ladies’ man personality to him and a deep interest in, I guess you could say, the supernatural and in psychedelics.

EM: What else do we know about Reed’s personal life? Morgan, you mentioned he was a ladies’ man?

MP: So Reed Erickson was primarily attracted to women, and before his transition he had one lesbian partner who is referred to in the research as Anne, though that’s not her actual name. She would prefer to remain anonymous. But after his transition and the breakup of that relationship, he ended up having a string of marriages with women who he had only met once or twice before he married them. And there’s some great photos of him attending balls with a woman on each arm.

EM: Yeah, in fact he was legally married twice. And, AJ, if I can ask you, Reed had two children with his wife Ailene. Do we know how?

AL: You know, I don’t know. At least in my own research in his, you know, personal papers, it wasn’t really obvious how they had children. I actually, honestly, like, it was sort of a question that I sort of declined to pursue, you know, as I honestly don’t know if they’re, if they were adopted or if his wife biologically parented the children.

EM: So, Morgan, it sounds like Reed is living a pretty extraordinary life for a trans man in those times—running businesses, married with kids…

MP: Sure. So due to his class position as someone quite wealthy, he was really accepted in society both for his relationships with women and his transition, which is really interesting when you think about the 1960s. There were very few people who could so openly and publicly transition, let alone maintain multiple marriages.

EM: It’s actually kind of mind-blowing when you think about it, especially given what the times were like. So, Morgan, when you say that Reed Erickson was wealthy, how wealthy are we talking about—and where did the money come from?

MP: Reed Erickson inherited a lead smelting business from his father and he later sold that for millions of dollars.

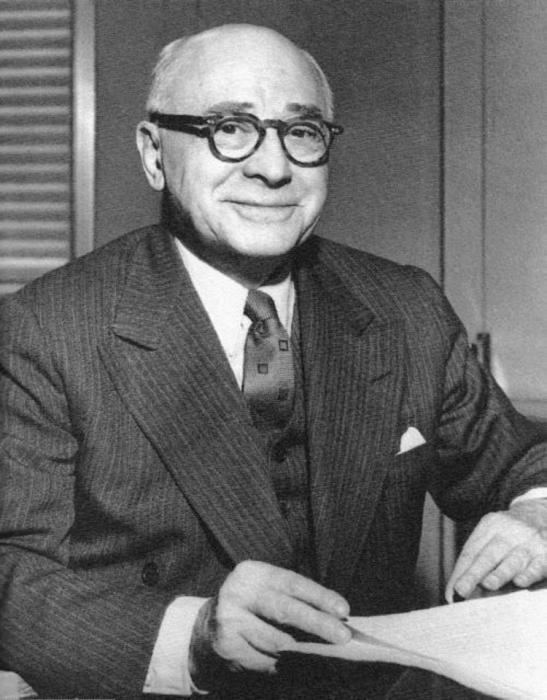

EM: Okay, so I have some more tape to play here. It’s a bit more from that 1966 gathering that we played earlier. We think Reed Erickson was at the meeting, but he doesn’t speak on the tape. But you’re about to hear Dorr Legg talking about the new Institute for the Study of Human Resources, which is the nonprofit organization that Reed told Dorr to set up so that Reed could fund ONE’s work. And you’ll also hear Dorr introducing the groundbreaking sexologist and endocrinologist Dr. Harry Benjamin.

———

Dorr Legg: This very handsome folder describes the Research Institute, which Mr. Erickson had us set up and you will see that he is the president of it. And Ailene Ashton, who is now Mrs. Erickson, is one of the directors. Dr. Benjamin here is one of our national advisory board of trustees. Dr. Benjamin has just recently, within the past month or so, published a most important book, The Transsexual Phenomenon, which is really a landmark on this topic.

Dr. Harry Benjamin: Yes, well, first of all, I want to thank you. Erickson came to me and says, “I know that you are interested in that, don’t you want to do some research on that?” And I said, well, I didn’t say it, but I thought, well, 20 years ago I would have said “yes” right away, but my stage of life, to start something new… But then he said, he gave me some details and said, “It can be for 30, for three years, and it can be an amount up to nearly $100,000.” How can anybody refuse that?

———

EM: It’s probably worth pointing out that the $100,000 the Erickson Educational Foundation offered Dr. Benjamin back then would be the equivalent of about $775,000 today.

AJ, how influential was the Erickson Educational Foundation, or for short, the EEF?

AL: I mean, I think the thing that the EEF tends to be most noted for, rightfully so, is particularly his work to back Harry Benjamin’s early research. I mean, Benjamin of course would go on to develop the Harry Benjamin Standards of Care, which today is called WPATH. But like then and now the Benjamin Standards have been the globally dominant standards of care for trans health.

Some providers are moving away from them and a lot of trans communities have critiques of the Benjamin Standards, but Benjamin like really kind of made trans health care into a thing. You know, Erikson’s early work in backing that was, I think, really really influential, allowing, you know, trans medicine and trans health care to develop. I think the EEF also did really important work in the 70s helping to develop a national network around trans activism and advocacy.

EM: And what else was Erickson funding, beyond the homophile and trans stuff?

AL: Part of like the EEF’s mission was to like fund research considered, you know, too imaginative or controversial for other sources of support. So he was a backer of work on dream telepathy and telekinesis. The EEF was a big backer of the early New Age handbook A Course in Miracles. He also worked with the researcher John Lilly for many years, and Lilly’s mainly known for his work with dolphin communication.

EM: Yeah, and just for the record, the EEF’s mission was, quote: “to provide assistance and support in areas where human potential was limited by adverse physical, mental, or social conditions, or where the scope of research was too new, controversial, or imaginative to receive traditionally oriented support.”

And back to you Morgan. From what I’ve read, Reed recruited some interesting people for the Erickson Educational Foundation.

MP: In his own weird style, he set up as the leader of that foundation Zelda Suplee, who was the well-known owner of several nudist colonies and actually has the distinction of being the first full-frontal nude within Playboy magazine, but was by this time much older, odd character.

EM: So Reed Erickson was funding a whole range of research and organizations via his educational foundation. To give an indication of how important Reed’s philanthropy was to ONE, according to research by Dr. Aaron Devor from the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada, Erickson’s money accounted for up to 80 percent of their budget.

We’re going to fast forward now to 1980 because if we stop in the 1970s, it seems like Reed Erickson is funding all this great work by ONE, and folks will have the impression that ONE worked in friendship and solidarity with Reed and they all lived happily ever after. But that’s not exactly what happened. For one thing, Morgan, Reed wasn’t well, was he?

MP: Well, by the 1980s Reed Erickson had developed a number of health problems, not least among them cancer, I believe of the bladder, so he was a little worse for wear, but over and above all of that, by the 1980s Reed Erickson was fully addicted to ketamine and cocaine, which were ruling his life at that time.

EM: Anything you’d like to add to that, AJ?

AL: Like, Reed Erickson was always sort of known for his sort of unorthodoxies, and I think as the ’70s progress, a lot of his idiosyncrasies like start to sort of present more and more like mental illness. He’s sort of increasingly becoming kind of erratic, by appearances paranoid and delusional, increasingly making accusations of folks that he works with, and alienating a lot of his, you know, colleagues and collaborators. By the end of the 1970s at least for, you know, ONE’s purposes, Erickson’s like becoming more challenging to work with.

EM: And so, Morgan, when did the tensions between ONE and EEF, or really the organization’s principals, Dorr Legg and Reed Erickson, start to show?

MP: Well, I think there had always been tension between the two of them because they were quite strong personalities. But by the end of the 1970s, cracks are starting to show as Reed continued to move into his more particular tastes, for example his extrasensory research.

And Dorr Legg wanted to move more strongly in the direction of gay rights. So that became a major problem. But what really put the nail in the coffin is that the ONE offices were beginning to literally crumble. So Reed Erickson invested $1.9 million in buying a very fancy estate, which used to be run by a Christian mission, and transforming it into a graduate school, library, archive, and the offices of ONE.

EM: AJ, can you tell us more about the Milbank Estate deal? I understand it was pretty dramatic?

AL: Erickson arranged to buy this historic estate. Reportedly he purchased the entire thing in cash, in gold South African Krugerrands. He claimed to have single-handedly driven down the price of gold globally with the purchase and claimed to have saved hundreds of thousands of dollars on the purchase by doing that. And the plan was to use the mansion for shared headquarters with ONE. Erickson reneges on the deal and announces his intention to, you know, evict ONE from the premises. And the estate then becomes the center of this protracted acrimonious legal battle.

Erickson was very emphatic about his concerns that ONE was maneuvering to cut both the EEF and trans issues broadly from their work, and that Dorr Legg was sort of looking to cut Erickson out of the estate once they acquired it, and that he was specifically threatening to out Erickson as trans in order to do so.

Erickson of course had a very public profile around trans issues, seemed to have been out to most of his friends and colleagues, but was kind of circumspect around being out about his trans status beyond that.

In fact, when ONE sued Erickson for possession of the estate, the lawsuit like very conspicuously named Erickson, not just by his legal name, but also the name that he was given at birth. And, you know, he had changed his name many, many years previously. There’s no legal reason to do that beyond it being just simply a kind of hostile move to publicly out Erickson.

I think that, you know, were Erickson’s mental health and chemical dependency, like, difficulties, were those an ingredient? Probably, but I think it’s also frankly kind of transphobic hostility from Legg and ONE may well also have been a contributing factor to that deteriorating relationship.

EM: And things really did deteriorate, Morgan, didn’t they?

MP: Reed at one point had Dorr trapped inside the estate by welding the gate shut behind him, and at another point when Dorr refused to take his hands off the gate, Reed ordered the workers to just simply weld his hands to the gate, which didn’t happen, but was quite something to say.

EM: So the two sides have this protracted legal battle. And, Morgan, how long did that battle last?

MP: The legal battle between Reed Erickson and Dorr Legg actually went from about 1983 to just after Reed’s death in 1993. They fought for 10 years in the courts and literally on the estate, over and over and over again throughout the years, even while Reed was living in exile in Mexico to avoid drug charges.

EM: And what happened to Reed in the end?

MP: In the end Reed had fled America from these outstanding drug charges and was living in the somewhat ruined remains of his Love Joy Palace Ashram that he had built decades before. By the 1990s, he had very serious cancer, a number of other outstanding health problems, and an incredibly costly addiction to ketamine and cocaine, the combination of which resulted in a downward spiral of health until finally in 1992 he passed away.

EM: And what do you think Reed Erickson’s legacy is?

MP: The influence of the Erickson Educational Foundation cannot be stressed enough. We today would not have trans health care, period, without the funding and the information provided by the Erickson Educational Foundation. It was the first organization in the world that actually provided support and information to trans people, both through its newsletters and publications as well as an in-person office where people could call or drop in to receive information.

Essentially, the framework that trans rights organizations use today in terms of collecting resources by area and distributing them to trans people in need, is based off the work of the Erickson Educational Foundation. So without that, the modern trans movement as we know it would not exist.

EM: And how do you think he’d like to be remembered, Morgan?

MP: He was actually a fairly private person so I don’t know if he’d want to be remembered all that well, but I think he would be best remembered through all of the projects that he funded, including the dolphin communication research.

EM: And, AJ, on those same questions about, you know, what is Reed Erickson’s legacy and how would he like to be remembered… You think the esoteric, New Age-y stuff is important too, right?

AL: Yeah, um, ironically, from the vantage point of today, his work on like gay and trans issues are sort of his more respectable contributions. And I think that like, both for myself and for trans communities that respond to his work, thinking very broadly, following the sort of EEF’s mission to sort of like expand human potential, you know, kind of eclecticism and like creativity that he brought to work, he was doing a lot of really interesting weird experiments and like developing other forms of knowledge, other forms of insight, you know other ways of inhabiting the body. I don’t think that sort of his interest in like mysticism was, you know, disconnected from his conditions living as trans in the years that he did.

I honestly think that this sort of like his quirkiness and his willingness to sort of like be very unorthodox in support supporting a whole host of different kinds of issues is something that like speaks powerfully to trans communities today.

EM: AJ Lewis is a postdoctoral fellow at Grinnell College, who’s working on a history of trans activism. And Morgan M Page is a writer, activist, and host of the trans history podcast One from the Vaults. Reed Erickson is such a complicated and fascinating figure and I’m so glad he’s being un-erased from our history, so thank you both for helping to tell his story.

MP: Well, thank you both so much.

AL: Oh, yeah. Thanks so much for your time. Also it was great talking.

———

EM Narration: Reed Erickson died on January 3, 1992, in Mazatlan, Mexico, which is where he’s buried. He was 74 and left behind two ex-wives, two children, and a legacy that’s still being assessed to this day. Reed’s nemesis, Dorr Legg, died two years later.

The Milbank estate legal case was settled several months after Reed’s death and the estate was later sold. In the years since, the Milbank mansion has been used as the setting for numerous movies and television programs, including a reality TV show called Beauty and the Geek.

There’s just one more thing I’d like to share about Reed Erickson. I think it’s possible that my mother might have met him, but she’s long gone so I can’t ask her. Reed Erickson stood with my mother at the intersection of New Agers and nudists. While I might be one of the most vanilla gay men walking the planet today, I went to my first ashram with my mother when I was 8 years old in the mid-1960s.

By the late ’60s mom had an Indian guru and went by the name Shivani. And by the mid-’70s she was immersed in exploring self-actualization, massage, and taking her clothes off. She even graced the cover of a nudist magazine and proudly showed it to me, as much as I begged her not to. You can’t un-see that sort of thing. And people wonder why I turned out the way I did.

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: executive producer Sara Burningham, extraordinary producer Josh Gwynn, production coordinator Inge De Taeye, production intern Claire Tighe, social media producer Denio Lourenco, photo editor Michael Green, and our guardian angel, Jenna Weiss-Berman. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers. We’d also like to thank Dr. Aaron H. Devor, chair in transgender studies and professor of sociology at the University of Victoria in Canada, for his input.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. A special thank you for all the archive tape you heard in this episode, all sourced from the ONE Archives.

Season four of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, and our listeners—like Kathy Danser, Daltin Danser’s incredibly supportive mom. Thanks, Kathy!

Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. Our website is also where you’ll find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

So long! Until next time! And from all of us at Making Gay History, we wish you a happy, healthy, and progressive new year.

###