Quentin Crisp

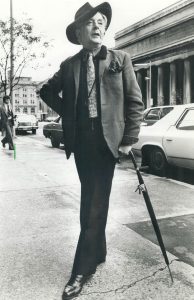

Quentin Crisp, London, 1980. Credit: Simon Dack Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

Quentin Crisp, London, 1980. Credit: Simon Dack Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.Episode Notes

From a young age, Quentin Crisp was determined to be himself—makeup, painted nails, dramatically dyed hair, and all—even if it consigned him to a life of poverty and isolation. Hear the author, raconteur, and provocateur in a 1970 conversation with Studs Terkel before he found late-in-life fame.

Episode first published November 12, 2020.

———

For a brief overview of Quentin Crisp’s life, read this 1999 New York Times obituary. Find out more in the three installments of Crisp’s autobiography: The Naked Civil Servant (1968), How to Become a Virgin (1981), and The Last Word (published posthumously in 2017; excerpt here).

To better understand Crisp’s world, read this short history of LGBTQ rights in the UK or take a deeper dive with Peter Ackroyd’s Queer City: Gay London from the Romans to the Present Day and Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957 by Matt Houlbrook. Also check out LGBTQ-related items from the London Metropolitan Archives and the Museum of London.

Crisp’s first memoir, The Naked Civil Servant, brought him to the attention of documentarian Denis Mitchell. Mitchell interviewed Crisp in his famously grubby one-room apartment for the investigative current affairs program World in Action; watch the segment here.

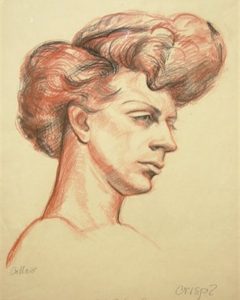

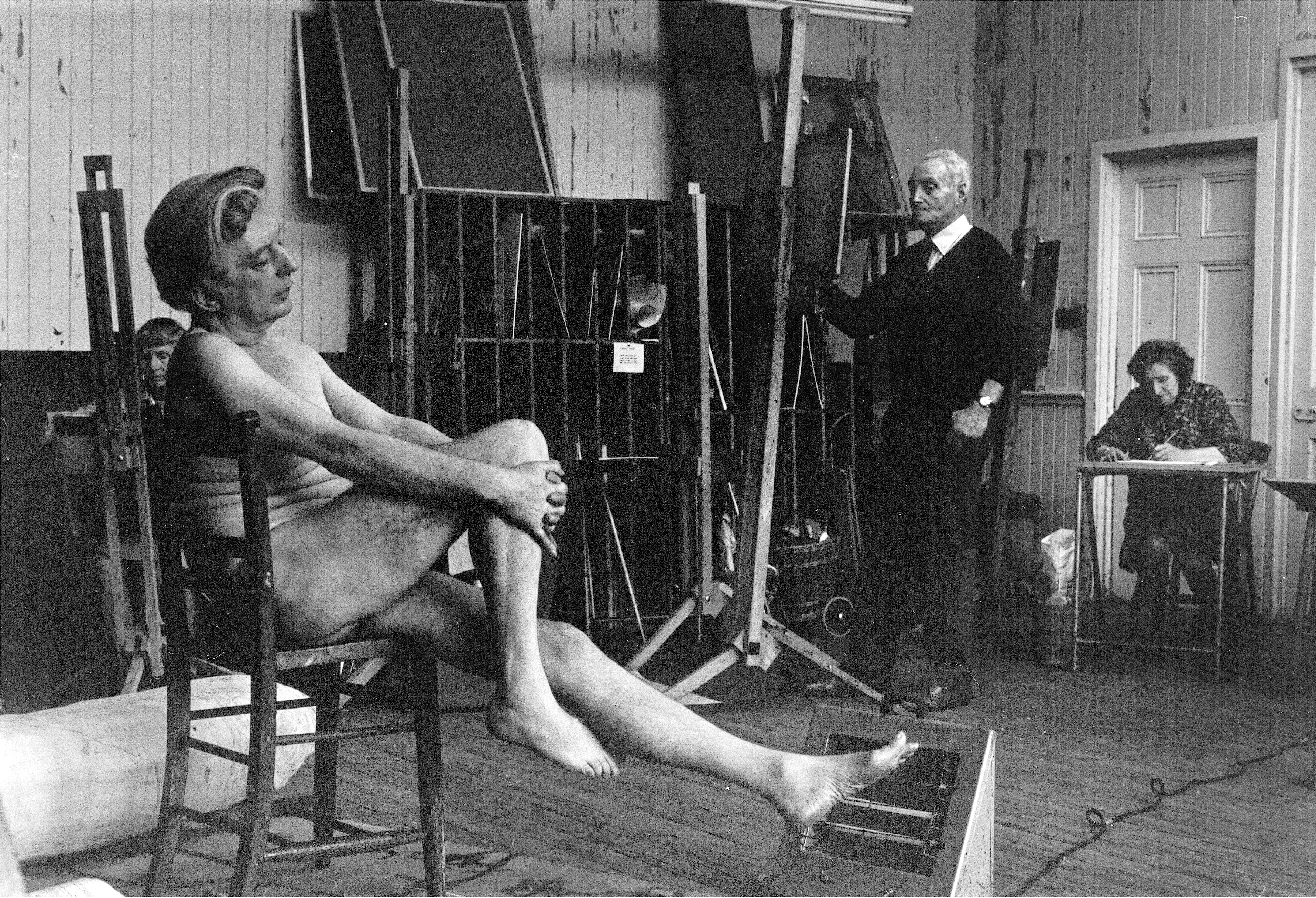

For most of his adult life, Crisp earned a modest living by working as an artist’s model. You can see some of the portraits he sat for (as well as some glamorous photos of young Crisp by Angus McBean) in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection.

In 1975, The Naked Civil Servant was adapted for the screen. See Crisp introduce the film here. John Hurt starred as Crisp and earned a BAFTA award for his performance. He reprised the role in a sequel over 30 years later.

Following the film’s success, Crisp toured the UK and North America with a celebrated one-man show titled An Evening with Quentin Crisp. You can watch it in its entirety here. The show opened at the Players Theatre in New York City on December 20, 1978. Crisp revisited the play 20 years later to rave reviews.

In 1987, the musician Sting was inspired by Crisp to write the song “An Englishman in New York.” Crisp starred in the music video, which you can see here. Watch Sting talk about the song and his friendship with Crisp in this interview.

In addition to his autobiographies, Crisp also wrote books like How to Have a Life Style (1975), Doing It with Style (1981), Manners from Heaven (1985) and Resident Alien: The New York Diaries (1997), a compilation of columns he wrote for the New York Native, a gay New York City newspaper.

Crisp was a frequent guest on talk shows throughout the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. Watch a few of his appearances on Late Night with David Letterman here.

Crisp had plenty of detractors in the LGBTQ community and was criticized for the provocative statements he made equating homosexuality with mental illness, dismissing gay liberation, and downplaying the AIDS epidemic (though he later donated regularly to AIDS organizations). Watch him talk on the subject of gay liberation here.

In 1993, Crisp played Queen Elizabeth I in Sally Potter’s Orlando. You can see him in the trailer here and read his recollections of the experience here.

Crisp’s estate is tended by his longtime friend Phillip Ward. Ward also co-edited the final installment of Crisp’s autobiography and created Crisperanto: The Quentin Crisp Archives from personal effects left to him in Crisp’s will to keep his memory alive. Watch Ward in conversation with Eric Marcus here.

Crisp died on November 21, 1999. Listen to his friends and family share their memories of Crisp in this recording of his memorial service.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History.

This season we’re reaching beyond my own collection of interviews to bring you voices from the Studs Terkel Radio Archive. The archive holds more than 5,000 programs that the pioneering oral historian and broadcast legend recorded for WFMT radio in Chicago between 1952 and 1997.

And that’s where we found a half-century old interview with Quentin Crisp—a writer and performer who was known, above all, for being unapologetically himself. Quentin was born Denis Pratt on Christmas Day 1908 and grew up in suburban London. In his early 20s, he left home, changed his name, and began to cultivate a dramatic personal style that provoked both curiosity and hostility in a rigidly conformist age. With his dyed hair, makeup, and painted nails, Quentin asserted his right to exist as a feminine gay man, even if that meant isolation and hardship.

When he was 59, Quentin gained notoriety when he published a memoir called The Naked Civil Servant. Studs Terkel’s interest was piqued. In 1970, he sat down with the writer in his dingy London apartment.

Quentin was famously anti-housekeeping, stating that “after the first four years the dirt doesn’t get any worse.” His apartment hadn’t seen a dust rag, mop, or paintbrush in ages. But to Quentin, it was home.

———

Studs Terkel: You describe where you live as a ward.

Quentin Crisp: That’s right, yes. I described it as a ward and as a prison cell, but it’s also a sort of, kind of asylum. It’s also an escape. And as I’ve never been able to get hold of, um, fortune or life or fate, or any of these things, um, I’ve had to use a retreating method of living my life. That is to say, I have had to move into a cell and then make it a home because I’ve no other way of doing it.

ST: You have no other… Why do you call this a cell or an asylum?

QC: Well, because it’s what I’m left with. You see, I’ve lived a life where all I’ve ever been able to do is just lurch forward whenever I saw a chink of light anywhere.

When people say to me, “Why did you choose to do this or that?” it doesn’t make sense because I’ve never chosen anything. All I’ve ever done is just think, I could do that. I mean, all the jobs I’ve had were the jobs I could get because that’s been my whole life. The people I know are the people who weren’t ashamed to know me. The places where I’ve been in are the places where the landlady didn’t turn me out. And so, of course, as soon as I arrived here, where I’ve been for 30 years, it was absolutely marvelous from my point of view.

ST: You’ve been in this one-room flat for 30 years? I see a gas plate. A charred teakettle. You have a variety of… all your possessions, all your life belongings here in this room…?

QC: All my life belongings are in this one room.

Quentin Crisp at his London apartment, 1948. Credit: Photo by Popperfoto via Getty Images.

ST: Your trousers somewhat ragged, your hair is gray. You say all you have are your friends who would not be ashamed to know you. Why should they be ashamed to know you?

QC: Well, this is because I’m a self-confessed homosexual. In England there are very few. I now realize, from having been in touch with Americans since my book came out, that homosexuality in America is organized.

Um, on one occasion, some society, which is devoted entirely to homosexuals, took over a theater so that all its members could see the same show on the same day. Now in England you couldn’t get four homosexuals into the theater.

ST: Do you mean to tell me that the homosexual is freer in America than in England? You mean in England that they’re less open than in America?

QC: Oh, much less open, much less. You could not get a homosexual society going here. You can have a club, which is taken over by homosexuals. And then the proprietor makes up his mind what to do: whether to turn the first half-dozen of them out or whether to let them come and let the place become known as a homosexual club to other homosexuals.

It’s the English temperament. You see, in England, they don’t even like sex. Long before we got to peculiar sex. And this is, um… In France they regard almost all English people as homosexual because they speak so badly of women. I mean, after all, in America, a woman is called “honey” and “sugar.” But in England, she’s called “old girl.” I mean, who wants to be an old girl?

ST: What interests me mostly in this conversation, Mr. Crisp, is you yourself, your life, study of loneliness perhaps, of friendship, madness. What you call madness and what you call sanity, because you describe this room… And perhaps beginnings. Who is, who is Quentin Crisp?

QC: Well, from childhood on I was homosexual of course, that is to say I lived in this dream of being a woman. If you’d asked me when I was young what I wanted to be, uh, heaven knows what I would have said, but I wouldn’t have said I wanted to be an engine driver. And I wouldn’t have said that I wanted to be an admiral on a ship.

You see, the fact is, when I was younger, all I really wanted, of course, was to be a chronic invalid because then I would have been able to live at home forever. I would have been special. I would have been looked after.

Crisp school photo1921 group photo of Kingswood Preparatory School in Epsom, England. A white arrow points to Denis Pratt, age 12, who later became known as Quentin Crisp. Credit: Courtesy of Bourne Hall Museum.

ST: You wouldn’t have to face that which was outside, is that it?

QC: This is a huge part of it. First of all, to gather together all my mother’s attention by hook or by crook, even if it led to her disliking me, and secondly, to avoid the outer world because I felt so totally inadequate. And this never left me because I’ve never been able to do anything. The only job I’ve ever had where I understood what I was doing was being a model. Otherwise than that, I just was put into jobs by my father. Um, he tried to find me jobs when I couldn’t even get them. Then other people found me jobs, and I did them as well as I could. But everyone knew that I was hopeless.

ST: When you were a small boy and you had this feeling you were afraid of the outside world, you wanted to be the chronic invalid, so… was it a fear of growing up, was that it? If you had to grow up, you had to leave the home and go out into the world.

QC: If I had to grow up, I would have, comparison would be made between me and real people. See, while I was a child, uh, more or less everything is forgiven. But when you grow up, you’re not, they can see you’re the same age as other people with the same education. Why aren’t you forging ahead? Why aren’t you, um, amassing property, gifts, anything you like?

You see, I, I had the jobs, what you might call the odd jobs. I have the income that you’ve got left with after you’ve confessed this.

ST: You mean to say that you’re denied jobs on the basis of your homosexuality?

QC: No. I’m denied jobs because I can be seen to be homosexual. Um, you could go, you could apply for a job. And when you’d gone, the interviewers could look at one another and say, “I think he’s queer.” But what they don’t like is that you can be seen to be queer.

ST: Money and you were never very close.

QC: No, I’ve never earned more than 12 pounds a week in the whole of my life and never for long. And over the book, I made a small amount of money. But even that wouldn’t be enough to, to change my life. It’s just money I can cling on to until I need it most. But I’ve always, I’m always at the losing end. This is absolutely inevitable.

ST: Why is it inevitable that you are always at the losing end?

QC: If you’re on the outside, you’re just clinging on and the slightest rocking of the boat, you fall into the sea.

ST: When did you first realize that you were on the outside?

QC: I should think when I was about 18 or 19 or 20, but I’d never heard the word homosexual used then. So I imagined I was the only one.

ST: This now is some almost half-century… it was 40 years ago or so.

QC: It was 40 years ago. I’m now 61. Uh, yes, about 40 years ago. And since the subject had never been mentioned to me, I didn’t know it existed.

ST: How did your parents feel about you?

QC: Well, my father tried to behave as though the whole thing was sort of non-existent, um, he waited for it to pass. It never did. So he never spoke about it. He tried not to speak to me as far as he could. My mother alternately, um, indulged me and threatened me with the outer world. Um, I don’t think it goes on nowadays, but in the time gone by every parent said to its child, “You can’t go on like that when you go out into the world.” And they said it to me.

Nobody ever said, “I suppose, when you grow up, you’ll meet people as mad as yourself and you’ll get on alright with them.” These were the words I waited to hear.

Forty years ago, there were thought to be certain people who were homosexual and they were a separate race of people. And this of course is no longer so. We now realize that men are not heterosexual or homosexual, they’re just sexual, and this we didn’t know in the beginning, or I didn’t know anyway. And certainly my parents didn’t know. I don’t think my mother ever really understood homosexuality at all, but, and my father would only know what a male prostitute was.

ST: You practiced that for a time?

QC: Yes. I’ve been what’s called “on the game,” but it’s, there again I was a total failure because you’ve got to be very sharp and you’ve got to be very tough and you’ve got to have the nervous stamina of an ox, and all these things I failed to have. So that even a life of sin I couldn’t make a go of.

ST: You say, you couldn’t make a go even in a life of sin, you failed even at that.

QC: Even at that.

ST: And the purpose, I suppose, of the male prostitution, as with, for that matter, prostitution as we know it, was to make a dollar, I imagine.

QC: To make a dollar. And of course in those days, if you made 10 shillings out of one man, you were lucky.

ST: We’re talking now about money, aren’t we, at the moment? Money. We haven’t talked about love, have we?

QC: Well, no. That I don’t think I could have made a go of either even if I’d tried, but I recognized that love was out as far as I was concerned right from the beginning.

ST: Why was that?

QC: Well, I don’t think I could have coped. Who could I set up a house with, set up a flat with? It was, it would have been too difficult. What would have happened to him? He would have been reproached from morning till night. It would have been a sacrifice too great for anyone to make, because wherever I live, the whole neighborhood knows I’m there.

ST: Uh, that’s it… We should point out perhaps that, that Mr. Crisp, Quentin Crisp, dresses quite bizarrely, you did in the past. Today it’s less, less recognizable as that, but you were always, uh, you, you did this unashamedly. Of course you did. As a result, you say an acquaintance of yours might feel…

QC: Any acquaintance had to put up with quite a lot because to walk with me through the streets was to get anything from abuse to definite attacks.

ST: Have you been physically attacked?

QC: Oh yes. All the time. Abused, attacked, made fun of. This I expected. I didn’t know it would be as bad as it was. I assume, anyone assumes in England that if they wear a bizarre appearance that they will be made fun of. But it was worse than I imagined because I was followed by crowds in the street so the traffic couldn’t get by. So amazing was it. Well, now this doesn’t happen and I haven’t been attacked physically in years.

ST: There were days when you were followed by crowds in the streets. When was this?

QC: Oh, this was in the ’30s.

ST: The ’30s, what… Can you recreate the moment, the situation? Do you recall?

QC: Well, I got, you see… It’s very difficult for anyone who doesn’t remember such early times to, to get used to it. No man ever wore anything except a dark suit out of doors. To wear suede shoes was to be under suspicion. You, you, you had to search your appearance for any sign of effeminacy.

ST: I want to come back to those days when the crowds followed you.

QC: Uh-hmm… Well, um, this was chiefly in the West End of London, in the heart of London. And, um, if I was there, one or two would follow me and then other people would wonder what they were following and the people at the back in the end certainly couldn’t see who I was.

The police had to disperse the crowd. The police had to fight their way through the crowd and say, “Go away, there’s nothing to look at,” et cetera, et cetera, and get them to move on. This didn’t of course happen every day, but it happened quite a lot.

ST: What was the police attitude toward you?

QC: That I was a nuisance. But, um, it was years before I was actually arrested.

It was during the war that I was arrested, and this was, I think, simply because by that time I had exemption papers saying I was homosexual. So the police could stop you and say, “Can I see your identity card? Can I see your exemption papers?”

ST: Let me understand this now. You carry ID papers, exemption papers… You carry papers such as, say, a Black does in South Africa.

QC: That’s right. You did during the war, everybody did. If you hadn’t got your papers, you’d have to explain why you were still not in uniform.

ST: Oh no, but you… I see. The papers explain… therefore, the papers said you were homosexual.

QC: And this was the explanation of why I was not in the forces. I was not allowed into the forces because I was homosexual. Now, you might have papers saying that you are tuburcula—that you had tuberculosis, but you had to carry or have handy your exemption papers, exempting you from, um, a call-up from being in the forces. Now, once they’d seen these, they thought they were safe to arrest you.

I’ve seen all these changes come and go, but, fundamentally, the attitude toward, um, known homosexuals is still the same. The permissive society makes no difference.

ST: Someone who is different is still looked upon as what is hostile, this enemy, this alien—is that it?

QC: I think this is part of it. And I think another part is that, um, the charge is one of effeminacy, because if you’re what they call a butch homosexual, then I don’t think this would happen because what would they see? What, what signs, what tokens…?

ST: We should point out that a butch hom—is one who appears to be masculine in every way. Whereas you are a feminine homosexual.

QC: That’s right. And this is not only in my appearance, it’s in my voice, and it’s in my movements, and it’s in my preferences, my character. It’s everywhere.

ST: Then in your case, walking down the street, is that why you’re in the room so often?

QC: That’s why I’m here, because being outside is such a fag. It demands so much of me. I leave the room to go to work or to visit friends. I never go to a pub because there may be trouble.

If there’s a way of staying in, I’ll stay in. But this is partly of course laziness. Before I do anything I think to myself, could I possibly get out of this? And if I could, I do.

Um, apart from that, there is the effort I might have to make even to buy a box of matches. I might go into a shop, ask for the matches. This might lead the girl behind the counter to going into the backroom, to tell her mother and father that I am there and for them to come out and pretend to look for the box of matches in order to see me. I’ve got to live through all this. I’m not worried by it now. I’m not certainly, not wounded or hurt by it, but you, you have to bring a certain amount of consciousness to bear on this.

If you’ve had a lifetime of really worrying about whether people are following you. Um, whether they’re threatening you, how many people are following you, whether you’re alone in the street, whether it will be another hundred yards before you get to the main road—if you had to think about this for a lifetime, you become very, very conscious of other people. Well, now I’m not really afraid of people. There might be some special circumstances when I would be afraid. Otherwise I’m merely conscious of them and I rally my forces to, to meet the occasion, because everything is an occasion.

ST: Every—everything is an occasion.

QC: Yes. We, if you’re eccentric in any way, everything becomes an occasion.

Quentin Crisp, London, 1948. Credit: Photo by Popperfoto via Getty Images.

ST: What do you believe in?

QC: I believe in absolutely nothing. I can’t afford to, because I may have to change at any moment.

ST: Ah. Wait a minute. Why can’t you afford to?

QC: Because I’m the weakest person. The strong can say they believe, but the weak must accept everything. I must change my opinions every week, if necessary.

ST: But if you were weak, why would you deliberately, deliberately, put on those bizarre costumes and put on makeup and lipstick and walk down the streets? If you were weak, you wouldn’t do that. Would you?

QC: Well, I was of course stronger when I was younger. And, um, as I say, when I began, I didn’t know how tough it was going to be. I thought, oh, people may shout out to me, but I didn’t realize that I would actually be beaten up, and, and fairly constantly.

Um, this is due to several things. One, I was so poor that I had to live in the poor parts of London, where everything is tougher. And this means that you get more beaten up more often. Also, um, I think the fact that I am doing it, not merely doing it, but I’m seen to be doing it deliberately, defy, defying them, protesting, I think this annoyed them more than the mere fact of my being homosexual, because a lot of people who beat you up are quite used to homosexuals. Especially nowadays. They don’t like protesting homosexuals.

And of course, protestation is like a dru—drug.

ST: In what manner did you protest, you mean, you protest?

QC: Well, my appearance was one long protest. I obviously have at least some feelings of guilt, because all protest is a kind of guilt.

ST: You say you have feelings of guilt.

QC: Well, guilt is actually a strong word.

ST: Feelings of sin?

QC: Not really sin, not really guilt, but feelings of being different and of, certainly, of not of liking it. Um, I have known homosexuals who thought the whole thing was wonderful and amusing, an adventure, and so on. I’ve never liked it. I never wanted to be on the outside. I never wanted to be someone whose sex was an object of, whose sex was a subject of discussion.

If I’d been a woman, my sex would not have been the subject of discussion at all. I should never have had to explain myself, defend myself…

ST: You said guilt earlier. Are you religious?

QC: No, I have no religion. I have no religion and I suppose guilt would be the wrong word. Since guilt must refer presumably to trying to win or feeling you’ve lost the opinion of God.

Um, I’m not worried by, um, theories of God and I’m not really worried by society, but obviously if I were totally unworried by it, then a protest would not have been necessary, would it? So it must be that I’ve had to accept the fact of criticism. I’ve had to cope with criticism. I haven’t been able to ignore it.

And this is because I’ve not been a strong enough character, because if you were truly strong, you would simply neither confirm nor deny. And this is what I haven’t been able to do. When criticized, I protested.

ST: So therefore you were a protester, and being a protester, you were protesting chains you were forced to wear. So indeed then you were pulling at your chains, weren’t you?

QC: I was pulling at my chains and I now know this was a great mistake. Because what is freedom? It has to be inside you. It can’t be on the outside. Free to what? Total freedom doesn’t exist. Just, just, the young people of today speak of the revolution. Now the worrying thing about that is not the word “revolution,” but the word “the,” because there will be no revolution in that sense.

There will be no sudden moment at which everything changes. Revolution is a perpetual process. Beyond the horizon are other horizons.

ST: Well, we haven’t talked about loneliness, have we?

QC: No.

ST: Are you?

QC: Am I lonely? No, I’m quite often alone and have been from the, from the beginning. And I like this. I couldn’t cope with a life in which I lived with somebody. A lot of people say, “Isn’t your life lonely?” And I say, “Yes, but it’s something, one, that it’s just as well to accept, but also, I now actually prefer it.” Of course, when I was young, I hoped to meet somebody who would cherish me and look after me and admire me and all these things.

This never happened. And it never occurred to me that it didn’t happen because I wasn’t lovable. I assumed that it didn’t happen because I was homosexual. And this is a great fault which one must try not to get trapped in.

When you’re peculiar in some way, if you’ve only got one leg, if you’re homosexual, if you’re a drunkard, you still mustn’t attribute everything that happens to you to this one unique factor. Because it may be various other things.

Um, when on, um, Mr. Mitchell’s television program, I said I was waiting for death, any number of people rang me up and said, “This is terrible.” And I said, “Well, what are you waiting for?” And they said, “Well, I have too much to do to think about death.” Well, this is also no good. If you’re filling your life with events in order not to think about death, it would be better to think about it and get ready for it now.

ST: Does that thought obsess you?

QC: No, it doesn’t obsess me, but it is true. I don’t expect anything new from my life now. And this is because I’ve done and said and been the things that I can do and say and be. If I hadn’t, then I would still be waiting for the occasion to arise when I could, um, express some more of myself…

———

EM Narration: Quentin Crisp might have thought that he’d live out his life within the four walls of his studio, but five years later, his world opened up in very unexpected ways. The Naked Civil Servant was adapted into a TV film that made Quentin a celebrity. He developed a one-person show based on his life that drew large crowds and got him invited to New York. Quentin immediately took to the city, and at age 72, he moved across the Atlantic to the East Village, trading one shabby apartment for another.

Throughout his 70s and 80s he continued to perform on stage, and was a frequent guest on talk shows and at fancy New York dinner parties. He also wrote books and movie reviews, made television and film appearances, and even showed up in an ad for a Calvin Klein perfume.

Not everyone admired what Quentin had to say. He was a gay icon to some, but others took offense at his prononcements against the gay liberation movement. He got himself in hot water when he called AIDS nothing more than a fad, although he later quietly donated money to the American Foundation for AIDS research.

In his final memoir, The Last Word, Quentin expressed his biggest regret. He wrote, “The only thing in my life I have wanted and didn’t get was to be a woman … If the operation had been available and cheap when I was young … I would have jumped at the chance … I would have told nobody. Instead, I would have gone to live in a distant town and run a knitting … shop and no one would have ever known my secret. I would have joined the real world and it would have been wonderful.”

Quentin Crisp died on November 21, 1999. He was 90.

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: senior producer Nahanni Rous, co-producer and deputy director Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Kevin Seaman, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Denio Lourenco. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman and our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Studios, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season eight of this podcast is produced in association with the Studs Terkel Radio Archive, which is managed by WFMT in partnership with the Chicago History Museum. A very special thank-you to Allison Schein Holmes, Director of Media Archives at WTTW/Chicago PBS and WFMT Chicago for giving us access to Studs Terkel’s treasure trove of interviews. You can find many of them at studsterkel.wfmt.com.

Season eight of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, proud Chicagoans Barbara Levy Kipper and Irwin and Andra Press, the Small Change Foundation, and our listeners, including Joan Davidson. Thanks, Joan!

Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. Our website is also where you’ll find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

So long! Until next time!

Quentin Crisp, Chelsea Hotel, New York City, 1995. Credit: Photo by Rose Hartman/Getty Images.

###