Mattachine Midwest

Episode Notes

A half-century ago, Studs Terkel interviewed three members of the homophile group Mattachine Midwest: the organization’s president, a student activist, and lesbian pulp author Valerie Taylor. Join them for a wide-ranging and laugh-filled conversation about gay liberation both personal and political.

Episode first published November 26, 2020.

———

Mattachine Midwest was founded in Chicago in 1965 in the aftermath of a brutal police raid on a gay bar called Louie Gage’s Fun Lounge. You can learn more about the raid in this clip from the documentary Quearborn & Perversion. For a deeper dive into Chicago’s LGBTQ history, watch Out & Proud in Chicago (Mattachine Midwest is featured at 46:30) or read Queer Clout: Chicago and the Rise of Gay Politics by Timothy Stewart-Winter.

Read Mattachine Midwest’s constitution, bylaws, first meeting minutes, introductory address, and first two newsletters (no. 1 and no. 2), courtesy of the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives, Chicago’s LGBTQ archives. Historian John D’Emilio writes about Gerber/Hart in Queer Legacies.

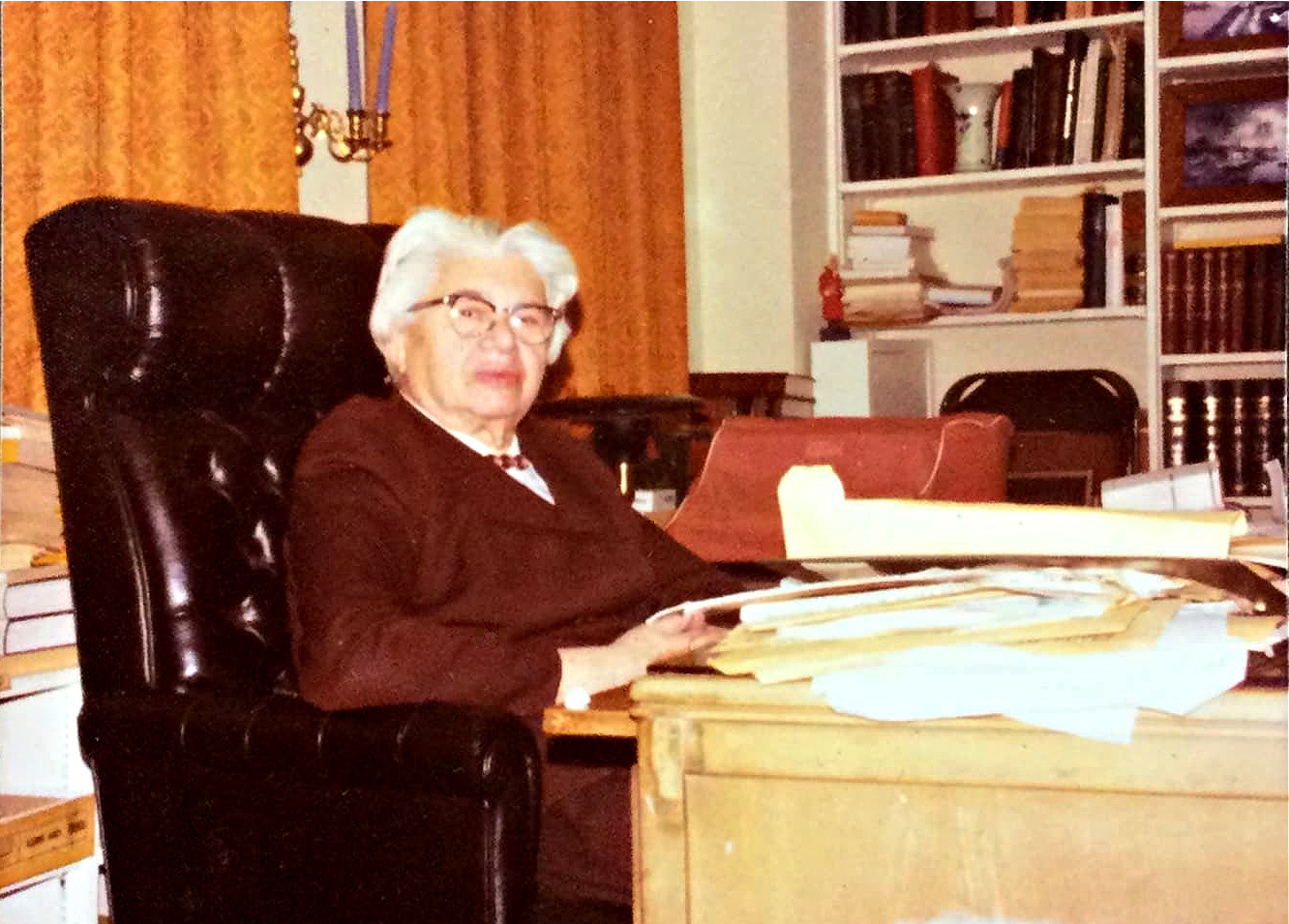

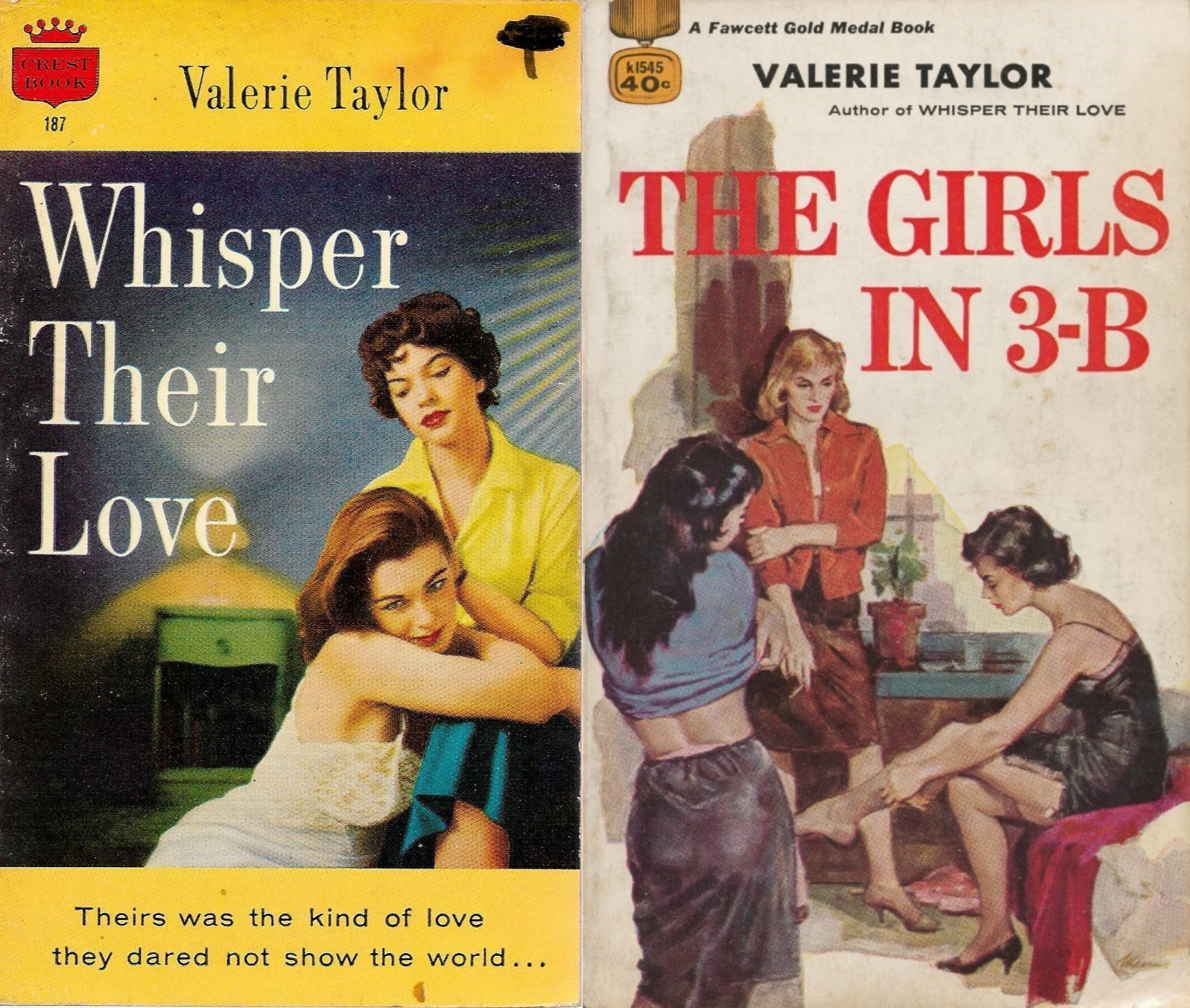

Valerie Taylor (the pen name of Velma N. Tate), a Mattachine Midwest cofounder and one of the three people featured in the episode, was also a pioneer of lesbian literature. Starting in the late 1950s, she became a well-known writer of lesbian pulp fiction. You can check out some of her titles here and read her 1960 novel, Stranger on Lesbos, here. You can find a full list of her published works in this Lesbian Herstory Archives newsletter.

Learn more about Taylor in this tribute by Marcia M. Gallo, author of Different Daughters—A History of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Rise of the Lesbian Movement. Taylor’s papers are preserved at the Cornell University Library here; you can view some of the photos in the collection here. Studs Terkel included an interview with Taylor in his 1995 book Coming of Age: The Story of Our Century by Those Who’ve Lived It, which you can borrow online here.

Taylor was in a long-term relationship with Chicago LGBTQ legend Pearl Hart, another Mattachine Midwest cofounder. Read about their relationship here.

Hart was known as the “Guardian Angel of Chicago’s Gay Community.” She was also mentioned in the Making Gay History episode featuring DOB trailblazer Shirley Willer, which you can listen to here.

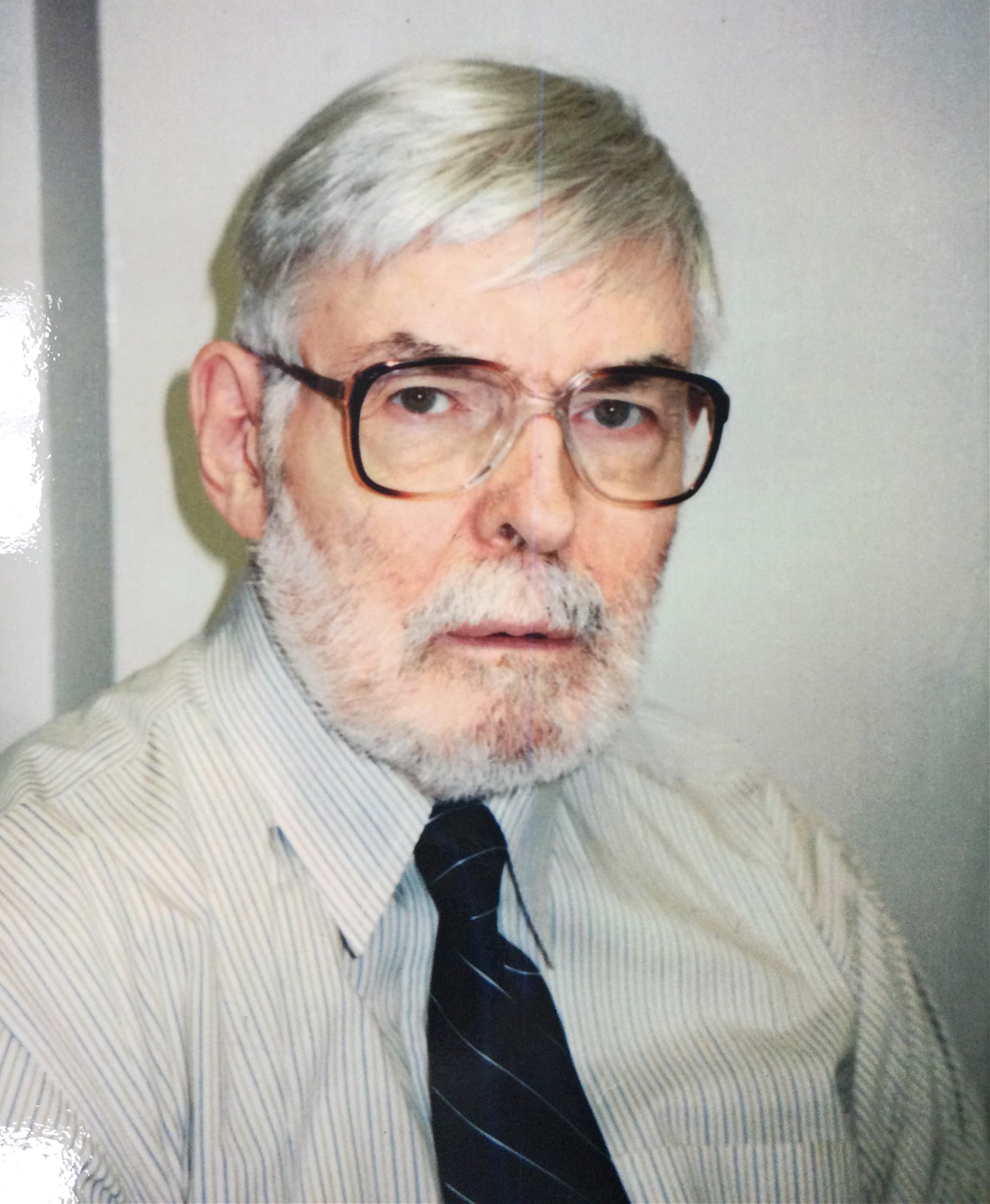

Jim Bradford was the pseudonym of activist James B. Osgood. Osgood first received Mattachine Society newsletters on behalf of a closeted friend. He later joined Mattachine Midwest and became its president. Guided by his Quaker faith, he was a vocal critic of the Vietnam War, the Nixon Administration, and police brutality. He wrote numerous letters to the editor—in Quaker publications, LGBTQ publications (page 15), and the New York Times. Learn more about him in his obituary and his memorial announcement.

Henry Wiemhoff was a cofounder of Chicago Gay Liberation, a more radical gay rights organization than Mattachine Midwest; read about the group here. He co-organized and spoke at the world’s first Pride march, held in Chicago on June 27, 1970. He later moved to New York City, where he helped establish the New York chapter of Black and White Men Together. In 1978, Wiemhoff wrote to the New York Times to call out the New York City Police Department for failing to protect gay men who were being beaten in the heavily wooded “Ramble” section of Central Park; you can read his letter here.

In the episode, you’ll hear discussion of what Studs Terkel called “the John Wayne Syndrome,” a cousin of what we now call toxic masculinity. For a primer on toxic masculinity, watch this clip or read this article. (For a palate cleanser, hear how performance artist Taylor Mac remade Ted Nugent’s homophobic “Snakeskin Cowboys” into a gay ballad here [at the 12:30 mark].)

In the episode, you’ll also hear the panelists mention Dr. Alfred Kinsey, whose work provided talking points for some of the early Mattachine discussion groups. Dr. Kinsey authored two landmark books about sexuality: Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948), and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953). The Kinsey Institute at Indiana University offers extensive information and research on human sexuality and gender.

———

Episode Transcript

Studs Terkel: By the way, how did the word “gay” come into being? I’m curious.

Valerie Taylor: Nobody seems to know really.

Henry Wiemhoff: It does seem to be a product of the “gay subculture,” though.

Jim Bradford: I became aware of it when I was first in college around 1949-50, and I, I don’t know.

HW: It’s ironic because the gay subculture has been anything but gay.

ST: Yeah.

HW: It’s this kind of reverse psychology. When, when you’re really stomped on, you try and make a joke out of it.

VT: Somebody obviously gay has suggested “glum” as the heterosexual alternative. “I was sitting, I was sitting in this glum bar.”

[Laughter.]

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History.

We’re back with another interview drawn from the Studs Terkel Radio Archive. The archive holds more than 5,000 programs that the pioneering oral historian and broadcast legend recorded for WFMT radio in Chicago between 1952 and 1997.

The history of LGBTQ organizing in Studs’s hometown of Chicago goes all the way back to 1924. That’s when Henry Gerber, a Bavarian immigrant, founded the Society for Human Rights, the first documented gay rights organization in the U.S. But the police soon swooped in, arrested several members, and the group dissolved. It would be a quarter-century before gay people tried to organize again: in 1950 the Mattachine Society was founded in Los Angeles, and in the years that followed, like-minded groups sprung up around the country.

Chicago’s Mattachine Midwest organization got its start in 1965. One of its founders was Studs’s close friend Pearl Hart, a civil rights attorney who became known as the guardian angel of Chicago’s gay community for her tireless battle against police harassment.

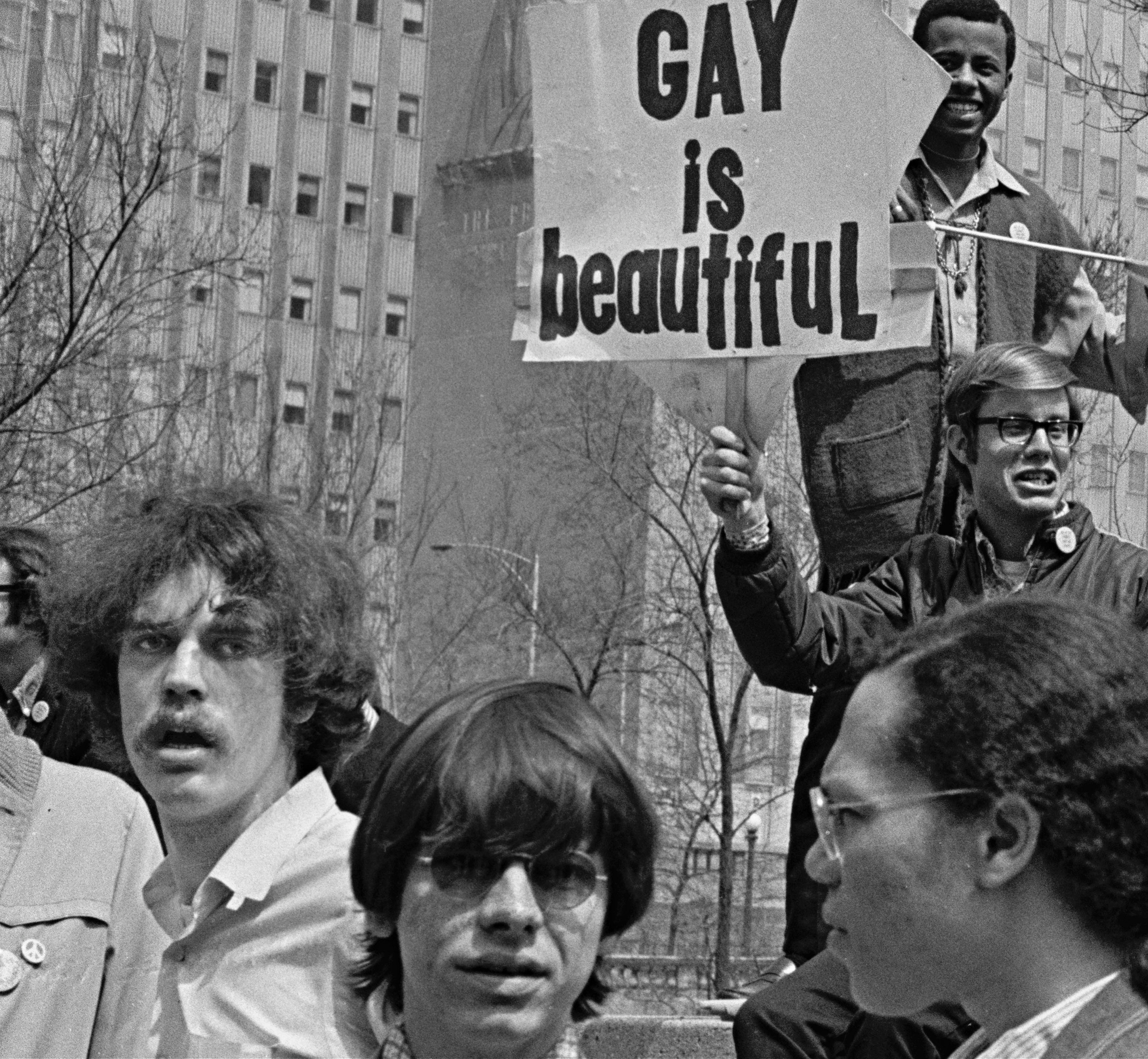

A few months after the Stonewall uprising, Studs interviewed three of the organization’s members: Valerie Taylor, Jim Bradford, and Henry Wiemhoff.

Valerie Taylor was the pen name of Velma Tate, another Mattachine Midwest co-founder. She was a 56-year-old divorced mother of three and the author of several lesbian pulp novels. She was also Pearl Hart’s longtime partner.

Jim Bradford was the pseudonym of James Osgood. He was a 37-year-old librarian and then president of Mattachine Midwest.

And Henry Wiemhoff was a 23-year-old student at the University of Chicago.

Let’s join the spirited trio in Studs’s studio, in an interview first broadcast on February 19, 1970.

———

ST: We’re really talking about freedom, aren’t we? The quest for freedom and the quest for openness in an open society as to who we are as individuals, physically, politically, socially, sexually. Isn’t that what it’s about? People of all minority groups… I suppose, could you… Valerie, would you describe being a lesbian or homosexual being a member of a minority group?

VT: To some extent I suppose it is. The best estimate I know is that from 1/20th to 1/10th of the population have ac—have, or have had, active homosexual experience. It’s impossible really to get any… Naturally, you’re not going to take a census and get honest answers on a matter like this. But I think that the male homosexuals feel this much more than women do.

ST: Why do you think that is?

VT: Society seems to be dreadfully hung up on the sex life of males, at least in this country. I don’t know how it is in other places. Um, men are not supposed to have affectional friendships, and they’re not supposed to stay single, and they’re not supposed to share apartments. And it’s only now that Henry’s generation is coming out with long hair and ruffles on its shirts and so on, and, and confessing to an interest in gourmet cooking and so on. Uh, a lot of these things which we believe to be socially conditioned have been regarded until recently as being sexually conditioned.

ST: I mean, Jim Bradford, you’re over 30. I was thinking as Valerie’s talking, and Henry of course is 23, and apparently, Henry’s generation, there’s a slight gap—and today, a generation is no longer 20, 25 years, it’s five, 10 years, you know. If you, Jim, uh, Henry is much freer than you were when you were his age, isn’t he?

JB: Oh, definitely than I was at that age, of… Yes. I think, uh, I have sort of loosened up as I’ve gotten older and had more experience. I remember the first meeting I went to was Mattachine of New York in 1959. And the cops didn’t raid the first meeting or the second meeting, so I decided it would be all right. Now, uh, a year ago, I was out in San Francisco and several active organizations out there planned, a, uh, support demonstration in front of the federal building on July 3, as a gesture of support for the annual picketing of Independence Hall—it’s called Annual Reminder Day.

And, uh, I knew the president of SIR, Society for Individual Rights, who said, “Why don’t you come and join us on the podium?” Well, I gulped once or twice, but I said, “All right, I will.” With the net effect that I was televised when a couple of years before I would never even appeared on radio. So there’s a certain liberation that comes with this, this sort of participation. You simply feel that, uh, these things are your own business and helping other people free themselves becomes part of your business. And it’s just great to do.

HW: So much of, of what gay people are afraid of is the result of an internalization and almost an exaggeration and distortion of what society has told us about ourselves and about our place in society. Um, so much of liberation in that sense, uh, comes from just standing up and saying, “I’m gay.” And seeing that, you know, you don’t have a heart attack on the spot, or you don’t, you aren’t murdered by someone. Um…

ST: I’m thinking of the phrase “power.” See, they have the button “Gay Power.” Do you think this liberation, this openness, you think it came about, uh, as, uh, in some way related to the Black revolution?

HW: Oh, I think, I think clearly, if nothing else, then a matter of, uh, taking one’s cues—and not necessarily one’s ideas, but one’s cues—from, from the Black, Black revolution.

Um, I was in Mississippi in 1966 with the Meredith Freedom March, and had done quite a bit of civil rights work in Chicago and around. And it gradually became quite clear to me that in some sense it was, I don’t wanna say hypocrisy because I don’t think it was hypocrisy, but there was something, there was something wrong when I could work for what I felt right for other people, and yet couldn’t do the same for myself.

And I’m not willing to pretend anymore that I’m any different than I am. I have found that in not pretending and not trying to play a game anymore, that I can live a full life and be happy. And there’s no reason why other people can’t do the same thing.

ST: So we come to the question of pretending…

VT: And it’s sexuality…

ST: Monogamy, polygamy, homosexuality, heterosexuality, … Pretending to be that which you are not.

VT: Kids used to be taught about masturbating. Is—are we allowed to discuss masturbation on your program?

ST: Well, you’ve done it.

[Laughter.]

VT: But it was a perfectly… Parents used to think, you know, it was a perfectly terrible thing and you tied the kid’s hands up or something and slapped him. And you taught him his brain was going to decay or something. And now I am pleased to find from my daughter-in-law that the baby books tell you all, all little children masturbate and you shouldn’t pay any attention to it. People used to have all these terrible guilts, and the whole thing was based on a misconception. You see, there is a parallel, I think.

ST: So we come back to the question of guilt…

VT: Yeah.

ST: We come back to the question of it. Who has, uh, who has established this matter of guilt and innocence?

HW: I don’t really think I’ve ever felt guilt. I’ve felt anxiety and perhaps, uh, anxiety that wasn’t quite proportionate to the consequences of, of my being homosexual. A lot of people do feel a tremendous sense of guilt. And I think the responsibility for that has to be squarely laid on the shoulders of the church. The church has said that if you want to be truly religious, you have to be this, and gay people just can’t be.

ST: When you’re talking about the church, of course you mean any church…

HW: I mean the church…

ST: Religion generally.

HW: Religion, yeah. Christianity, specifically, Judeo-Christianity.

ST: In your case, Jim?

JB: I think probably roughly the same thing has applied to me. I’ve felt anxious, but not particularly guilt-ridden. And I’ve always felt, which probably says more for the family I was raised in and my parents than anything else, that I’ve always felt that when it came to a showdown that, well, the preacher was wrong, not me.

ST: Family… I suppose this question often comes up, uh, discovery on the part of family… Was, was that, was that a problem here in your case, Henry?

HW: Well of course, um, homosexuality is something that every family might talk about occasionally. It comes up in conversations, and I can remember specifically, my family was, uh, rather skitterish about the subject when it ever came up—snide remarks, perhaps, something like that. And I was very, very much taken with the fact that my family, when they, when they were confronted with it, didn’t know anything about it, but were very much concerned and wanted to know what it meant. What did it mean to be gay? What was it that they could do to support, support me in that kind of a situation? I think really the problem in large part is a problem of ignorance.

JB: They think—well, for example, if you’ve ever traveled abroad the first time, you don’t know what to expect, you expect everything to be different. And once you sort of get used to it, or maybe by the second trip, you realize that the similarities outweigh the differences. I think that’s it with us. People think that we’re incapable of love. We’re incapable of long-term relationships, we’re incapable of holding down a job. My partner and I have been together, we’ve known each other almost 17 years. We’ve lived together 15 years. So this proves that it can be done.

ST: Uh, when did you first sense, for example, that somebody kept you apart or you were considered different? Valerie, you…

VT: Well, I don’t think that my experience is typical of lesbians because in the first place I have been married. I have three sons, slightly older than Henry, so I, if I act maternal towards him, I hope he’ll forgive me. Uh, in fact, I have two grandchildren whom I dote on. Also, of course I have seven published lesbian novels, and this gives me a very good out. I have never been picked up in a gay bar, but if I were, you see, I could say I was doing research.

[Laughter.]

HW: Yeah. I, I think the real question isn’t, you know, why are we gay, or why are other people straight, but why is it that we’re restricted in our, in our abilities to love on a, on an emotional or a physical level both. People, as people, uh, regardless of gender or sex, um, it seems that society is, is repressive of, of sexual feelings.

VT: Well, doesn’t a lot of this go back to property and inheritance? In the old days, a wife was her husband’s property and he had to be sure that she wasn’t laying someone else because the children had to be his. Jim, I’m sorry, if that word offends you, I could have said worse words.

JB: [inaudible] … permitted on WFMT.

VT: Can you say “lay” on WFMT?

[Laughter.]

ST: I think [inaudible] up in the control room is howling as I am. Valerie’s marvelous…

VT: Well, “having sexual relations” sounds so terribly sterile somehow.

[Laughter.]

HW: Right on.

VT: Um, because the children were the husband’s inheritors of his property, and it was a big property deal.

ST: I wonder if Valerie isn’t touching on something very, terribly strong. You know, perhaps at this moment, this is a rather critical and exhilarating though traumatic moment in the history of man, isn’t it?

HW: I think we’re at, at a crisis stage. We’re challenging a lot of things that we’ve inherited that are becoming increasingly irrelevant. And if we’re going to survive, we’re going to have to deal with these and reformulate these, uh, thought systems and structures so that they’re truly human.

ST: Perhaps we can go back to beginnings, the very nature of our society, and these fears of someone who is different. Valerie is saying that, uh, authorities are not quite as rough with lesbians. Is it perhaps because women themselves are considered, uh, less important in society?

VT: Partly that and, partly, I think, uh, women, gay women are a little better—if they don’t wish to say, “I’m a lesbian, I joined Mattachine, or I’ll join the Daughters of Bilitis”—it’s a little easier for them to conceal their identity.

HW: Val, don’t you think it has something to do with the fact that affection and tenderness expressed between women is something much more acc—

VT: Yes.

JB: It is.

HW: … accepted in society?

JB: It’s considered unmasculine for guys to respond toward one another the same, with the same degree of affection and openness of feeling as women are expected to.

HW: I was just thinking of the dance that we went to at the Eleanor Club. We—this was one of our first radical actions at the university. We went as gay people and we decided that this was part of personal as well as social liberation. And the girls took to it just like ducks to water. The reaction, however, to us dancing together—that is, the males in the group—was considerably different. This was something that was not accepted. This was something that was not, uh…

ST: Isn’t this something that I would call the John Wayne syndrome?

JB: Oh yeah. That’s it exactly.

ST: Isn’t this it? It’s the fact that masculinity is associated with violence, with anti-affection?

HW: Yeah.

ST: Yeah.

HW: This, this sense that, uh, in order to be male, in order to, uh, be masculine, you have to be able to compete and you have to be able to, uh, fight and, and, uh, express whatever, whatever feelings you feel towards another male in terms of, of, of aggression rather than, um, in terms of affection…

VT: We tend, I think all of us tend to feel that people who are very antagonistic to h—to homosexuals, you know, the guy who wants to beat up all the queers and so on, are afraid of their own homosexual component, basically.

HW: The reaction to our gay liberation group, we wrote an article in The Maroon and we’ve been running ads regularly. And it’s very interesting to see the differentials in, in responses to it. Um, straight people that, uh… I use the term straight—that’s another subculture term, and a lot of people…

JB: You mean glum, of course.

[Laughter.]

HW: Those people that are, are well-adjusted, uh, are all for it. They say, you know, “Yes, we agree. You’re an oppressed minority. Why don’t you do something about it?” You know? And they’ve been very receptive even to the point of being willing to wear the buttons that we’re making that say, “Out of the Closets and into the Streets.”

ST: Give me one of those buttons.

[Laughter.]

HW: We, we are thinking of, the group on, on campus at the University of Chicago, that perhaps one of the best things gay people can do right now is to form something, buy a house maybe, and I hesitate to use the word a commune, but a, a, a group living experience, in which gay people can prove to themselves that they can function effectively living closely together. I know this was quite an experience to me. I put an ad for gay roommates in The Maroon, and Shelly called. And Shelly’s female and I hadn’t realized that quite…

VT: [Laughs.]

HW: … you know, consciously, that females can be homosexual, too. And Shelly moved in. And the sense of, of living together and being able to share, you know, our experiences and, in talking during the day, eating dinner together, uh, that sense of loneliness then becomes, becomes something we hold in common and are able to, uh, do away with.

ST: What happened when you had that ad in The Maroon? Was there any, uh, repercussions?

HW: Was there any, any repercussions? There were a couple crank calls. I had expected them. But mostly I got calls from people on campus that weren’t looking for a place to stay, but felt extremely isolated and frustrated and afraid on campus and didn’t know how they could, uh, meet other people, how, who they could talk to about it. And it was then that I realized that there was a real need for a liberation, a wider sense than just a personal liberation.

VT: I had a letter last week from a young man, 21, who said in effect, “I am a homosexual. I don’t know any homosexuals. I’m afraid to go to the bars. How can I meet somebody?” He’d read a letter of mine in a newspaper.

HW: Yeah. This kind of hits at the, the whole problem of isolation, a sense of inferiority and guilt that, that’s been forced on gay people. And, and they don’t have to take it. I mean, especially now they’re realizing they don’t have to take it, but in the past, well, until I guess the Kinsey Report had a, a great effect…

VT: Yeah.

JB: Oh, yeah.

HW: … in, in showing that there were, you know, there were the, these percentages of people in society. And the sense of, of not being in some sense a freak, uh, had a great effect on people.

And more and more, we’re becoming aware that many of the things that have been accepted as, as normal, “normal,” have large elements of repression and, and oppression, and, uh, can in fact be subject to criticism and change. And the more people realize that, the less afraid they are of, of analyzing their own situation in those terms, too.

ST: This is interesting… I was listening because, in my mind, this is my—and correct me if I’m wrong—that the homosexual in the past has been regarded as rather conservative in nature.

JB: Well, there are all points of view on this. Now my honest feeling is that, uh, when we do public speaking, I usually start elaborating the types of jobs homosexuals have held simply to show that you find homosexuals from all, in all backgrounds—religiously speaking, economically, socially, and so on. So it’s really impossible to say they’re conservative, they’re liberal, they’re middle of the road. I think there may be a slight tendency towards some degree of conservatism, simply because of this need to hide…

HW: Mm-hmm.

JB: … problem. But on the other hand, it has gone the opposite way with me. I’ve been concerned about social justice since I was a kid. And I never got into the homophile movement until I realized, well, here’s something that’s, that’s suddenly growing up in our area. But it was more from the social justice aspect than from the me too aspect.

Uh, we were considering the possibility of having to picket the police headquarters several months ago, because we just couldn’t seem to get an answer out of them. That’s cleared up somewhat in the meantime, but at that point…

ST: You’re talking about entrapment now, you’re talking about the idea of entrapment?

JB: Well, the specific point was that several bars had been raided, and we thought it was unjustified, and we were having trouble getting through to headquarters to get an appointment to talk with them. That panned out, so we dropped the threat to picket. But when we were talking about it, an amazing assortment of people, some of whom had been at the same job for a great number of years and really had an investment in keeping hidden, if they were worried, came forward and said, “You can count me in if you’re gonna do it.”

HW: Really?

JB: “I’m not the least bit afraid. It’s about time we stood up and started doing things like this.”

ST: Has there been a lessening, or what has been the attitude toward authority, specifically police, uh, toward, uh, homosexuals? Towards lesbians, obviously less. I don’t know about police women, I’m not up on that.

VT: Oh, there are a lot of wonderful butch police women in this town, Studs.

[Laughter.]

JB: Valerie, they’ll never speak to us again after this.

VT: Sorry, sorry, sorry.

JB: I would say—and this, I think, is something that the, the faint of heart should ponder—since we have stood up to the police department and said, “Look, you’re really overstepping your bounds. You’re really violating our rights. Cut it out, or we’re going to bring suit against you. We’d rather sit down and discuss it with you. We’d rather see… We’d rather see what areas we can agree on and what your legitimate functions are. Uh, let’s do this, but if we can’t do it any other way, we’ll bring you into court, because you really have overstepped your bounds. You’ve taken our rights away and we’re not going to put up with it one bit more.”

HW: I think though that we hit… When we start talking about the police department, we hit a really deeper problem. And that is, the police really couldn’t be doing a lot of the things they’re doing, if they, in some sense, didn’t have the sanction of society and social attitudes.

ST: Yeah. We’ll probably fade out on this conversation just as we faded in, I was thinking. Valerie, so any thoughts come to your mind as we’re talking now?

VT: The main thing, if I could just say three words to the entire heterosexual world or uninformed world, they would be “homosexuals are people.” We’re just like everybody else, except in the matter of whom we go to bed with and what we do in bed really, isn’t all that different, you know? [Laughter.] And so it shouldn’t be…

ST: And really no one else’s concern, is it?

VT: Yeah, and so people shouldn’t think about us as though we were some different kind of a species. It’s, um, it’s a stereotype, you know, like the racial or ethnic stereotypes. And we’re just like everybody else.

ST: When you get right down to it, the theme of our discussion is freedom and humanity. Thank you very much.

HW: Wow, thanks.

VT: Thank you, Studs.

JB: Thank you.

———

EM Narration: A few months after the Mattachine Midwest interview was recorded, Chicago hosted the world’s very first Pride march on June 27, 1970, one day before New York City held its first march. One of the Chicago march’s main organizers was Henry Wiemhoff. Henry later moved to New York, and got involved with the National Association of Black and White Men Together, a gay multiracial and multicultural organization. He died from AIDS-related complications in 1995. He was 48.

Valerie Taylor went on to cofound an annual lesbian writers’ conference in Chicago, and continued to write both fiction and poetry. In early 1975, her partner Pearl Hart fell deathly ill. The hospital’s family-only policy kept Valerie from visiting her until it was too late. By then, Pearl was in a terminal coma. Valerie later moved to Tucson, Arizona, where she advocated for elder rights and the environment. She died in 1997 at the age of 84.

Jim Osgood died in 2003. He was 71. He and his partner had been together for nearly a half-century.

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: senior producer Nahanni Rous, co-producer and deputy director Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Jon Gordon, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Denio Lourenco. Thank you, as well, to Heather Brown for doing some impromptu research for us at Chicago’s Gerber/Hart Library and Archives. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman and our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Studios, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season eight of this podcast is produced in association with the Studs Terkel Radio Archive, which is managed by WFMT in partnership with the Chicago History Museum. A very special thank-you to Allison Schein Holmes, Director of Media Archives at WTTW/Chicago PBS and WFMT Chicago, for giving us access to Studs Terkel’s treasure trove of interviews. You can find many of them at studsterkel.wfmt.com.

Season eight of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, proud Chicagoans Barbara Levy Kipper and Irwin and Andra Press, and our listeners, including Janet Beauchamp and Retired United States Air Force Brigadier General David Cotton. David hopes that in sharing his military rank, others might feel encouraged by his indirect example to realize it’s okay to be who you are. Thanks, David! Thanks, Janet!

Whether you’re new to Making Gay History or a longtime fan, sign up for our newsletter so you’re the first to know what we’ve got coming up. You can do that at makinggayhistory.com. Our website is also where you’ll find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

So long! Until next time!

###