Martha Shelley

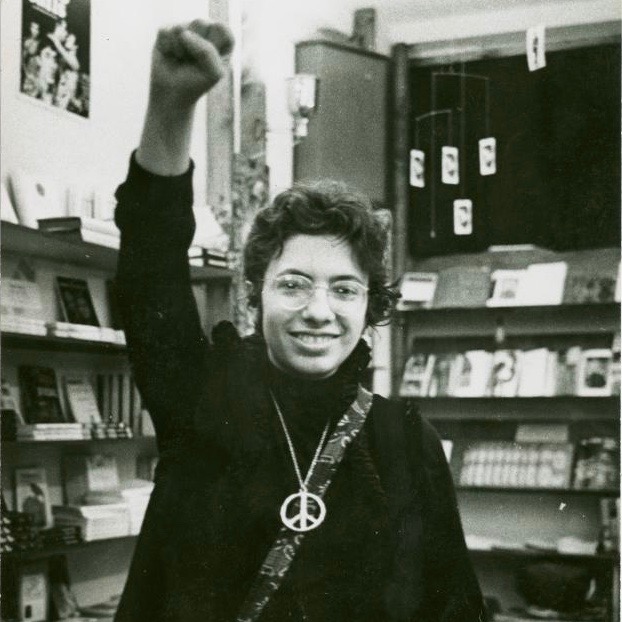

Martha Shelley at the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in New York City's Greenwich Village, 1969. Credit: Photo by Diana Davies courtesy of the Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Martha Shelley at the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in New York City's Greenwich Village, 1969. Credit: Photo by Diana Davies courtesy of the Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Episode Notes

Brooklyn-born Martha Shelley was a rebel. She didn’t like being told what to do, wear, or say. She hated the lesbian bars, and even after joining the Daughters of Bilitis, she strained against the self-imposed limits of the homophile movement. All along, the 1960s revolution called to her.

Episode first published February 21, 2019.

———

From Eric Marcus: By the time I met Martha Shelley in 1989 at the home she shared with her then partner in Oakland, California, her battle to find a place for herself in the world was history. But during the turbulent years we cover in this episode, which focuses on Martha’s life from 1960 until the eve of the Stonewall uprising, Martha was at odds with the world—so much so that by 1968, the 25-year-old Brooklyn native found herself leading three different lives.

One Martha Shelley worked at Barnard College as a secretary. Another Martha Shelley was president of the New York City chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), an organization for lesbians. The third Martha Shelley read feminist literature and went to see 2001: A Space Odyssey while tripping on LSD.

Long before she understood the implications of her sexual orientation, Martha, who is white and Jewish, began to learn what it means to be different from her best friend in junior high school, who was Black. Martha told me during our 1989 conversation that her mother worried that if her daughter grew up with Black people, she would “get used to them” and end up marrying one. “You know what?” said Martha, laughing, “She was right!” Her partner at the time of our interview was a Black woman.

To learn more about Martha Shelley, explore the links and resources below. We’ll be back with the post-Stonewall portion of Martha Shelley’s 1989 interview in Making Gay History’s season five.

———

Learn more about Martha Shelley in this interview, which focuses on her involvement in the movement before and after Stonewall (the audio file is embedded below the transcript). Eric Marcus’s interview with Shelley is included in the first edition of his Making Gay History book (titled Making History).

Shelley has written fiction, poetry, and essays, and her writings have appeared in numerous collections, including the influential 1970 feminist anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful, edited by Robin Morgan. You can hear Shelley discuss her novel The Throne in the Heart of the Sea on Portland radio station KBOO here. Her memoir, We Set the Night on Fire: Igniting the Gay Revolution, will be published in June 2023.

Watch this 1989 interview with Shelley from the Lesbian Herstory Archives’ Daughters of Bilitis Video Project. To learn more about the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), read Marcia M. Gallo’s Different Daughters: A History of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Rise of the Lesbian Movement and be sure to listen to our episode with DOB cofounders Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, too.

In the episode, Shelley mentions how the FBI monitored DOB’s activities. To see samples of their investigative work, check out the declassified files collected on this webpage.

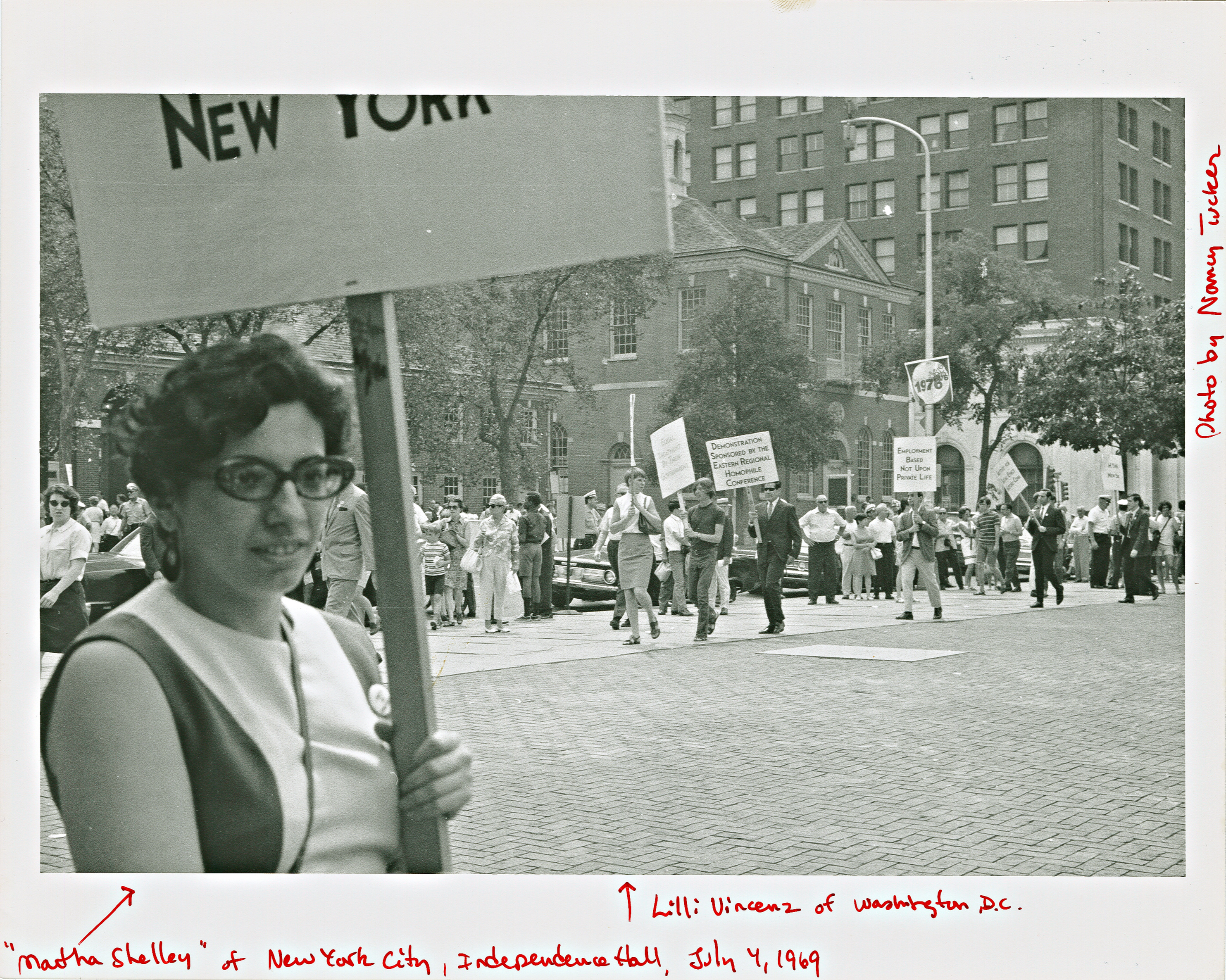

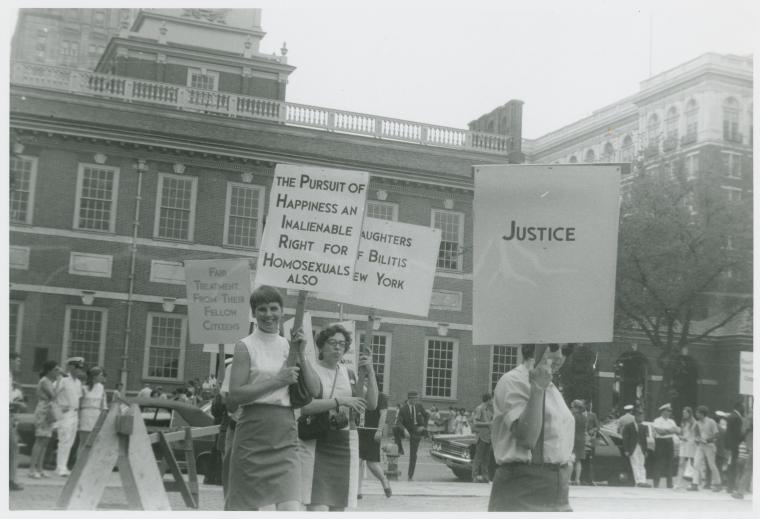

Shelley was one of the participants in the July 4 Annual Reminders, picket lines organized by homophile organizations from 1965 to 1969 at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. You can see footage of the 1968 Annual Reminder in The Second Largest Minority, a short documentary by Lilli Vincenz, here.

Shelley was a witness to the Stonewall uprising of June 1969. Watch her in the PBS American Experience documentary “Stonewall Uprising,” which features several Stonewall veterans as well as Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, who led the police raid on the Stonewall Inn. For more of Shelley’s reflections on Stonewall and its aftermath, check out this Windy City Times interview.

In this 1994 interview directed by N.A. Diaman, Shelley discusses her involvement with the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Lavender Menace. For more information about GLF, check out this page on the New York Public Library’s website. To explore archival issues of Come Out!, the GLF’s newspaper, go to OutHistory.org here. To learn more about the Lavender Menace (later renamed Radicalesbians), go here.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History!

This is the last episode of season four of Making Gay History. During this season, we’ve gone back in time to 1897 and the very first gay rights organization in the world, Magnus Hirschfeld’s Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in Germany. We’ve followed the stories of the very earliest activists in the U.S. who took inspiration from Dr. Hirschfeld and started the first organizations here. And we’ve traced the history of these organizations as they grew, became visible, and started challenging the status quo.

But as this season about beginnings draws to a close, we’re approaching a moment that many believe to be the beginning. The hot nights in June 1969 that have become the central story of the fight for LGBTQ equal rights, often described as where it all began. The next season of Making Gay History will focus on that inflection point, and its aftermath, but for now, we’ve got some more of the pre-Stonewall story to tell. It’s a story about transition, from the mid-century homophile movement to the era of gay liberation that followed. And Martha Shelley is going to help us tell it.

There were so many things that were familiar to me about Martha. She’s a fellow New Yorker. I’m from Queens. She’s from Brooklyn. We’re both Jewish. She’s first-generation American. I’m second. Our relatives spoke Yiddish. If you looked at photos of the two of us as teenagers, with full heads of curly brown hair, you might even say we were related instead of just from the same tribe.

That said, Martha and I couldn’t have been more different. She was a wild child compared to me. Martha came of age in the expansive and explosive 1960s, and found her place in revolutionary politics. I came of age in the mid-1970s and at 17 escaped my socialist working-class family for the ivy-covered walls of Vassar College, where I strived to pass for a private school preppy.

By the time I interviewed Martha in the late 1980s, we were both living on the West Coast, and she had more than a lifetime’s worth of activism behind her. About now I’d usually set the scene for you—you know, describe her house, her clothes, what she looked like. But, shamefully, I didn’t take any field notes that day. So I can’t set the scene, but I can tell you that Martha got involved in the movement before Stonewall, and played a crucial role afterwards. So I sat down with her at her house in Oakland, California, on Tuesday, October 24, 1989. I clipped the microphone to whatever it was she was wearing, asked her to take me back to where it all began for her, and pressed record.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Martha Shelley. Tape one, side one.

Martha Shelley: So I guess in 1960, I joined the first women’s judo class in New York City. What was I? Seventeen? And that’s where I met lesbians.

EM: In the judo class.

MS: Yeah. I mean it’s an all-women’s judo class, who’s gonna join? About half the women were gay. I started riding home on the subway with this one woman who was in the class, who was married. And I never thought anything about it except that her marriage was really not going well. She married to escape an abusive home. We used to pal around together. We played judo together, wrestle around. One day she invited me home for dinner. Her husband was a construction engineer. He went to sleep in the back room because he had to be up at five in the morning and we made love in the living room. And I went home thinking, Oh my god, I’m a lesbian.

EM: Now in 1960 you knew what that was. How, how, where did that awareness come from? Speaking with some women from earlier years… I remember asking one woman how she learned what she did about lesbianism, did she go to the library and look it up? And she said, “I didn’t even know the word to look up.”

MS: I read. I read like crazy. I hung around bookstores. I used to hang around the section where the trash novels were that had pictures of women on the front cover, lesbian pulp fiction, some of it pretty awful. I wasn’t able to get much of it, but I’d read enough that I knew what it was.

EM: In ’60 were you aware of any gay organizations, lesbian organizations?

MS: Yeah. I found out about that pretty fast, that there was a Mattachine Society and a Daughters of Bilitis, because that was in these books. Not the novels but the, you know, ones about homosexuality that were, you know, psychological tripe.

I left home when I was 19—packed up and moved into this cheap hotel. Went to lesbian bars, where I was miserable.

EM: Why?

MS: They were miserable places.

EM: Keep in mind that most of the people who’ll read this book most likely were not at lesbian bars in the 1960s. Describe what one was like.

MS: First of all, you couldn’t see into the place, for good reasons.

EM: What were they?

MS: Oh, security. You know, you didn’t want a bar that was full of women, where you could look in and see a bunch of women dancing together. That would have caused problems with the police, problems with guys who decided it was their masculine duty to come in there and beat these women up. It was just really dangerous.

So took a couple of tries around the block to find the sign of the place that I was supposed to go into. It was in Greenwich Village. I remember sort of skulking around. There was a guy at the door, a bouncer, I guess. And his job was to take your money, to check your ID, whatever. Then they hustled you for drinks and you had to pay for watered down drinks. The Mafia owned all of the bars in New York. It was known, and…

EM: How did you know it?

MS: Everybody knew it.

EM: How were the women dressed?

MS: Slacks. There were some women who wore femme clothes, beehive hairdos… Fifties clothes, even though this was really early ’60s. So there was, you know, butch vs. femme. And I hated that. I hated that from the beginning.

EM: Why? And I’m sorry, you may get tired of my “Whys.”

MS: That’s okay. I hated it because I didn’t want to be put in either of those categories. It seemed like amputating parts of what I did and making me follow rules about the way I should behave. You know, I became a lesbian… I think part of it was rebel—… Nowadays, the hip thing to say is it’s inborn. I’m not so sure of that. I think maybe that’s part of what went on. But I think that… I have had a long time, long time strong feelings about not submitting to authority and to rules.

I had a chance to join the military when I was in high school and… This was the Air Force that came around looking to recruit people at my high school. I said, “Could I be a pilot?” They said, “Girls can’t be pilots.” And I said, “You think I’m going to march around and do discipline like these other recruits and not have a chance to be a pilot? Get lost.” So I always had a strong feeling against being pushed into a role or made to follow orders that didn’t make sense to me. And the idea of having to dress like a man, act like a man, and follow those rules didn’t make any sense. And I certainly didn’t want to follow all of the female rules that I’d been rebelling against ever since I was a child. So I didn’t like that.

EM: How did you dress then?

MS: I always wore slacks. Well, that’s not true. I had to go to work and I had to wear dresses to work in those days because you couldn’t wear slacks to the office. So as soon as I got home I would put on a pair of slacks or blue jeans. I think I liked blue jeans better than anything else. And I would wear a plaid shirt or whatever shirt I felt comfortable in. And I suppose that would be called butch. The ethos of the time said that the butch makes love to the femme. Well, I wanted to be made love to also. I didn’t mind wearing the same clothes I was wearing, but I didn’t want to be forced into not getting my needs met in bed. And that was the price of not wearing a skirt.

EM: How did you survive in that environment?

MS: I went to DOB.

EM: When did you start going to DOB?

MS: 1967. And I really felt good about that.

EM: Do you remember your first meeting? Can you tell me about it?

MS: I remember walking into the place. There was this one woman, Jean Powers. She used the name Joan Kent at the time. She signed people up. And I was going to use my real name. But she insisted that I not do that. She had been hounded by the FBI during her lifetime and she insisted the FBI might get hold of the mailing list. I thought it was silly, but I chose a pseudonym and then put “care of” my real name.

EM: What was your pseudonym?

MS: Martha Shelley. Then I just changed it to my real name. It’s now on my driver’s license.

EM: What was your given name?

MS: Martha Altman.

EM: Martha Altman. Which would you prefer I…? Oh, your legal name is now Martha Shelley.

MS: Yeah. It just got to be too much hassle to have both of them going at the same time. I thought it was incredibly dumb and I figured, you know, if the FBI wants to find us, they’re going to find us. And, of course, as it turned out later, they were looking. They were keeping an eye on us all the time.

But I remember it being in an industrial loft building. And it was dark and it was dingy. But it was better than the bars because we could hear each other talk. It wasn’t like being in a smoke-filled bar drinking, with a lot of noise, and you couldn’t hear each other talk and being hustled for drinks. We were there to talk to each other and to get to know each other as people.

And that was where I was really able to feel good about myself for the first time as a lesbian because… People who felt successful in the bars—maybe I’m wrong—but I have a feeling the ones who were successful were people who were really cute according to standard definitions of cuteness in the society, you know: blond, blue-eyed, whatever.

EM: Of which you’re neither.

MS: No. I’m Jewish and I look it. I’m just not your WASP type. Don’t look like a stewardess, never have. And I was able to meet people who would relate to me in terms of my personality rather than “here is a cute thing standing by a bar.”

Now, by 1967, there already was a women’s movement. So I was relating to that and that gave me a certain amount of ideology to buttress my feeling that, about roles, not liking roles.

EM: What was it, what did you learn during that time that changed your outlook?

MS: Well, I read The Feminine Mystique. And I had read Betty Friedan. I’d read Simone de Beauvoir. And I was starting to read whatever I could find on feminism, even if it was, you know, published half a century ago. So already ideologically was, had moved in that direction.

EM: And that direction being…?

MS: Towards a society in which your behavior isn’t determined by your sex.

EM: And in America of 1967, how did that characterize itself? How was behavior determined by sex in 1967, just for you in your own life and in the work you did?

MS: I was working typing in an office. End of question.

EM: Did you bring any of that… of what you were learning about feminist ideology to DOB?

MS: Well, when people… we would talk about relationships. How to make your lesbian marriage work. How to deal with your family. All of these things. I had my point of view and I was pretty articulate. I didn’t say it in terms of feminism but what I said was that… Oh yeah, I was against marriage, too. And I said I didn’t see why we should replicate the heterosexual society and try to recreate the relationships that I felt we had rebelled against. I didn’t realize that “we” hadn’t rebelled against them. I had. I was only really speaking for myself and couldn’t speak for other people.

EM: What was the organization doing at that time?

MS: There were meetings. There were guest speakers. And those usually were a psychologist who didn’t think that gay people were sick. So we always had a friendly psychologist on hand to reassure us that we were okay. Sometimes we’d have political discussions about what we could do to influence, I don’t know, legislation or something. I don’t think it was really conceivable that we could have much influence at that time. And there was the annual Fourth of July picketing at Independence Hall in Philadelphia.

EM: Did you go?

MS: Yeah, I went a couple of times.

EM: And what happened at that event?

MS: It was hot. If you were female you had to wear a skirt. If you were male you had to wear a white shirt and tie. So here we were, gay people trying to pass as normal. And I say that, you know, ironically because that wasn’t the way we really dressed, but we were trying to show that we were just as good and okay and middle class as everybody else, regardless of what we really were like.

EM: Did that gall you quietly?

MS: Oh, yes. It definitely did. I thought it was ridiculous to have to go there in a skirt. But I went and did it anyway because it was something to do that might possibly have an effect. And I remember walking around in my little white blouse and skirt, and tourists standing there eating their ice cream cones and watching us like, you know, the zoo had opened.

I was always aware of the outsider’s point of view. And what it did was it made it easier for me to be gay. I was used to being different. I was used to being an outsider. Being gay just added one more color to the rainbow of outsider experiences. And it fit in. It felt like it fit in with my personality of being a rebel and an outsider.

It was like, I could do whatever it was, you know, take a risk and survive it. It was like, that going to the march in Philadelphia… I could go out in the street and be gay, even in a dress or skirt, and I wasn’t going to get shot. So each victory that I survived gave me the courage for the next one.

EM: And going on the radio was one more step.

MS: Yeah. I was working for Barnard College as a secretary. I worked in the office of the person who was in charge of fundraising. Who, I didn’t know it at the time, but was an old dyke. She was 65 and she was going to retire that year. And I was the head of DOB.

EM: Oh, by then you were president of DOB.

MS: And I was making these public speeches. One time a radio station called up and they were doing a story on the sexual revolution. So I was supposed to be interviewed by this guy who did the radio show. He came to DOB and he interviewed me, and at the end of it I had a headache, because I often got headaches after being interviewed by these clowns because their attitudes and their questions were so obnoxious, humiliating, demeaning. To even have to answer them felt demeaning. But it was a job that I felt was important and I did it. Well, then the next morning I went into the office, and I’m drinking my first cup of coffee and the boss sails in. And she said, “Guess what? This guy was here from WOR radio last night interviewing the girls at Plimpton Hall,” which was the first integrated dormitory at Barnard College. You know, boys and girls could live in the same dorm. “And I just must stay up late tonight and listen to this radio program.” And I thought, Oh shit. She’s going to hear me.

EM: You were scheduled to be on or they’d already taped you?

MS: They had already taped me and I was scheduled to be part of the program.

EM: So she came in and said that she’s going to listen to the radio show.

MS: Right. So I didn’t know what to do. I wasn’t sure whether I still had a job or not. I mean, I walked around freaked out all day. At five o’clock I went up to my boss and said, “I’m going to be on that radio show tonight.” And she wanted to know why. And I said, “I’m representing an organization called the Daughters of Bilitis.” And she said, “What’s that?” And I said, “It’s a civil rights organization for lesbians.” And she said, “Well, that’s nice, dear. It’s wonderful that you young people are taking up all these causes.” And gave me the biggest wink and said, “Now help me out with my coat. I’ve got to go catch my bus,” or whatever it was.

EM: Did you realize what the big wink was for?

MS: Yup.

EM: You did.

MS: The next thing that happened… I was having an affair with the head of the Student Homophile League, a guy. We were…

EM: Bob Martin?

MS: Bob Martin, that’s right.

EM: Oh, my goodness. Paths cross… So you were having an affair with Bob Martin.

MS: Right. It was just… I mean, it wasn’t a very hot sexual affair. It was just more thumbing our noses at the universe.

EM: Did you tell anyone about it?

MS: Yeah. We used to walk into these homophile meetings arm in arm. It was a scandal. Because there were these seven organizations that were in New York, seven little homosexual organizations…

EM: So it’d be DOB, …

MS: Student Homophile League, Mattachine Society, and I forget the others. Some of them were just two people and a mimeo machine. So it was a scandal in a sense, but at the same time, because the two of us were so blatant and out there in public being pro-gay and, you know, being on demonstrations, they certainly couldn’t afford to throw us out.

EM: Just remarkable.

MS: It wasn’t like we were only sleeping with each other. It was just… Let’s just thumb our noses, right?

Well, he turned me on to LSD in the men’s dorm of Columbia University. And while I was tripping around took me to see 2001. It was a real blast of an experience. It shook a whole lot of my previous notions of reality. Now I went to the Bronx High School of Science, so I had a very rigid notion of what reality was, which they taught you in that kind of school. And all of a sudden I saw the great white light. And a lot of the teachings of Eastern philosophy weren’t just mumbo jumbo—this was reality. And it was a reality that I experienced directly. And it made a lot of sense, a lot more sense than the very linear reality I had grown up with. So that pushed me a little further over the edge.

And I was planning to leave my job at the end of the semester. I was offered another job at Barnard College even though, you know, I was openly gay and stuff. And I said, “No, thanks.” I had an offer of a part-time job doing typesetting in the Village for this one woman who had a typesetting shop and used to do typesetting for the Black Panthers on the side and all kinds of radical and artistic groups—whatever radical, political, and artistic group was in the community, somehow her typesetting shop was in the middle of it, doing some art work or layout, whatever. So I had this part-time offer. And I figured I would quit being in therapy, which I had been. Quit my job, move down to the Village, work part-time, and have the rest of the time to write and be a political activist.

EM: This was in ’69 now?

MS: That’s right. But it was not… It was before the gay riot. So here it was, the end of… The semester ended in June. And just around that time, end of the semester, right? June 28, Stonewall riot.

EM: Where were you when…?

MS: … the shit hit the fan?

———

EM Narration: It’s very unlike us here at Making Gay History to leave you with a cliffhanger. But you’re going to have to wait a few months, for our fifth season, to find out where Martha Shelley was when the shit hit the fan. We’ll be releasing season five in time for the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising this June. We’ll bring you the voices of people who were there, and the voices of people who weren’t, but who picked up the revolutionary ball and ran with it.

But before we leave Martha Shelley for now, I just want to let you know that she’s alive and well and living in Portland, Oregon, with her wife. They’ve been together since 1997. Martha is a writer and poet, and these days she’s working as a legal medical researcher.

You can check out our episode notes if you want to know more about Martha’s life and work. And keep your eye on this feed. We may drop in a bonus episode or two along the way. Or sign up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com and be the first to know what we’re up to.

———

Making Gay History is a team effort. Thank you to executive producer Sara Burningham and the rest of the Making Gay History crew: producer Josh Gwynn, production coordinator Inge De Taeye, social media producer Denio Lourenco, photo editor Michael Green, and our guardian angel, Jenna Weiss-Berman. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. Season four of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, and our listeners, including Cheryl Furjanic. Thanks, Cheryl!

There’s another way you can support Making Gay History. Click on the merchandise tab on our website and you’ll find Making Gay History t-shirts, tank tops, and hoodies. We’ve also got Making Gay History tote bags and mugs. So you can wear us, carry us, drink with us, and at the end of the day, lay your head on a pillow that says “I Am Making Gay History.”

So long! Until next time!

###