Lorraine Hansberry

Publicity photo of Lorraine Hansberry, 1955. Credit: Leo Friedman-Joseph Abeles, courtesy of Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library.

Publicity photo of Lorraine Hansberry, 1955. Credit: Leo Friedman-Joseph Abeles, courtesy of Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library.Episode Notes

In 1959 Lorraine Hansberry became the first Black woman to have a play produced on Broadway. Soon after A Raisin in the Sun made history, the 28-year-old writer and activist talked to Studs Terkel about racial and gender inequity and the role of art in confronting difficult truths about our world.

Episode first published October 15, 2020.

———

To learn more about Lorraine Hansberry, watch the documentary Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart and read Imani Perry’s biography Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry.

A list of Hansberry’s writings is available here. Watch the author talk about her craft in this 1961 episode of Playwright at Work.

Read Hansberry’s award-winning play A Raisin in the Sun here, listen to a BBC Radio version of the drama here, or watch the 1961 film adaptation, starring original Broadway cast members Sidney Poitier, Ruby Dee, Claudia McNeil, Diana Sands, and Louis Gossett, Jr.

In the early 1950s, Hansberry began writing for the Harlem-based leftist newspaper Freedom. The paper was the brainchild of Paul Robeson, the activist actor and singer whose Communist leanings attracted FBI scrutiny and got him blacklisted during the McCarthy era. The FBI kept extensive records on Hansberry, too; you can see her redacted 1,020-page (!) file here.

Hansberry and fellow writer James Baldwin were close friends and political allies. Hear them both (alongside Langston Hughes) in this 1961 panel discussion on “The Negro in American Culture.” In 1963, when Hansberry and Baldwin were invited to a meeting on race relations with then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, Hansberry did not mince words; read about the tense meeting here. And read “Sweet Lorraine,” Baldwin’s moving posthumous tribute to his friend, here.

Hansberry was an early member of the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB). By necessity, her engagement with the homophile movement remained hidden, but in 1957, the DOB’s magazine, The Ladder, published two letters she submitted. You can see the first one below, signed with her married name initials, “L.H.N.” Go here to watch Eric Marcus in conversation with DOB scholar Marcia Gallo as they discuss Hansberry’s involvement with the group.

To learn more about DOB, listen to our episode with the organization’s co-founders Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon and our first episode with Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen, who worked on The Ladder as the magazine’s editor and photographer, respectively.

Hansberry also published four lesbian-themed stories in The Ladder and ONE magazine under the pseudonym Emily Jones: “The Anticipation of Eve” (1957), “Chanson du Konallis” (1958), “The Budget” (1958), and “Renascence” (1958).

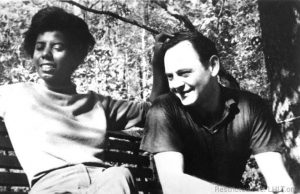

Hansberry’s lesbian social circle included the writer Patricia Highsmith and future LGBTQ rights icon Edie Windsor. In 1960, it also came to include Dorothy Secules, a longtime tenant in the building on Waverly Place in New York’s Greenwich Village that Hansberry purchased with earnings from A Raisin in the Sun. The two fell in love and began what would be Hansberry’s longest lesbian relationship. For more on her romantic life, read the article “The Double Life of Lorraine Hansberry.”

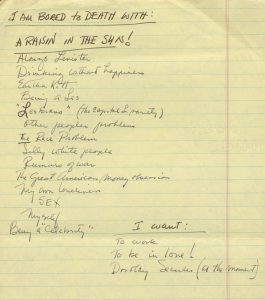

Hansberry didn’t officially come out until nearly a half-century after her death. In 2014, her estate at last unsealed diaries and other writings in which Lorraine revealed that she was a lesbian. You can see the 1960 datebook entry with her lists of “likes” and “hates” mentioned in the episode below.

Hansberry’s papers—which include unfinished work as well as letters and diaries—are kept at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which tends her legacy together with the Lorraine Hansberry Literary Trust.

In the episode, Hansberry praises the music of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, but makes clear her disdain for the DuBose Heyward book on which the opera is based. Learn about the complicated history of Porgy and Bess in this article and listen to its most enduring aria, “Summertime.”

After her death, Hansberry’s ex-husband and literary executor, Robert Nemiroff, adapted her unpublished writings into a biographical play entitled To Be Young, Gifted and Black: Lorraine Hansberry in her Own Words. In 1969, Nina Simone, whose politics had been greatly affected by her friendship with Hansberry, recorded the song “To Be Young, Gifted and Black” in her memory.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History.

This season we’re reaching beyond my own collection of interviews to bring you voices from the Studs Terkel Radio Archive. The archive holds more than 5,000 programs that the pioneering oral historian and broadcast legend recorded for WFMT radio in Chicago between 1952 and 1997.

And that’s where we found a 1959 interview with Lorraine Hansberry, the writer and activist best known for her landmark play, A Raisin in the Sun. It was inspired by her family’s battle against housing segregation in Chicago, where Lorraine was born in 1930. When she was 7, her parents bought a house in a white neighborhood in defiance of a covenant that banned sales to African Americans.

In their new neighborhood, Lorraine was the target of verbal and physical abuse. And one night, white vandals threw a chunk of concrete through a window, narrowly missing her. Lorraine’s father, who was a prosperous businessman, was often away for work, which left Lorraine’s mother to guard the family. She kept a pistol at the ready.

In A Raisin in the Sun, it’s the working-class Younger family that comes face to face with segregation and racism. The play earned Lorraine the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for Best American Play—she was the first Black playwright to win the award, and its youngest ever recipient.

Lorraine died when she was only 34. She had never publicly acknowledged that she was a lesbian. But in 1957 she wrote two letters to a magazine published by the Daughters of Bilitis, the nation’s first organization for lesbians. In the letters, she voiced her support for the group and drew analogies between the social and political struggles of women, lesbians, and African Americans.

A year later, she published four lesbian-themed stories under the pseudonym Emily Jones. By then, Lorraine had quietly separated from her husband, Robert Nemiroff, a Jewish song writer and book editor.

It’s now May 12, 1959, and Lorraine Hansberry is in conversation with Studs Terkel at her mother’s Chicago apartment. She’s visiting from New York, where A Raisin in the Sun has been playing to enthusiastic crowds on Broadway.

———

Studs Terkel: Lorraine… May I?

Lorraine Hansberry: Sure.

ST: A question—

LH: I’m going to call you Studs.

ST: A question is often, I’m sure, is asked you many times. You may be tired of it. Someone comes up to you and says, “This is not really a Negro play, A Raisin in the Sun.” They say, “This is a play about anybody.” Now what do you say?

LH: That’s an excellent question, uh, because invariably this has been the point of reference. People are trying… I know what they’re trying to say. What they’re trying to say is that this is not what they consider the traditional treatment of the Negro in the theater. They’re trying to say that it isn’t a propaganda play. That it isn’t a protest play—

ST: No message play.

LH: And that it isn’t something that hits you over the head, and the other remarks, which have become cliches themselves, as a matter of fact, in discussing this kind of material. So what they’re trying to say is something very good. They’re trying to say that they believe that the characters in our play transcend category. However, it’s an unfortunate way to try and do it because I believe that one of the most sound ideas in dramatic writing is that in order to create the universal you must pay very great attention to the specific.

In other words, I’ve told people that not only is this a Negro family, specifically and definitely culturally, but it’s not even a New York family or a Southern Negro family. It is specifically South Side Chicago—uh, that kind of care, that kind of attention to the detail of reference and so forth. In other words, I think people will, to the extent they accept them and believe them as who they’re supposed to be, to that extent they can become everybody. So I would say it’s definitely a Negro play before it’s anything else. Universality, I think, emerges from truthful identity of what is.

I don’t know what everybody is talking about when they talk about drama in American theater that has been hitting them over the head on the Negro question. They keep alluding to some mysterious—a body of material which allegedly did this. I, for one, can’t recall that we have had anything approaching a great number of protest plays or so-called social plays about Negroes.

Uh, it seems to me there’s a preoccupation and a sense of guilt or something that some elements are so afraid of what they feel that they’re already anticipating something that hasn’t been true.

ST: This is a very interesting comment you make here.

LH: We need a few protest plays as a matter of fact.

ST: I’m thinking of Walter Lee Younger. You call him the, the focal character, the protagonist of the play, Walter Lee Younger.

LH: I suppose, thematically, what he represents is my own feeling that sooner or later we’re going to have to make principled decisions in America about a lot of things. In other words, we’ve set up some very materialistic and, uh, limited concepts of how the world should go. Sooner or later I think we’re going to have to decide on them. In other words, I think it’s just as conceivable to create a character today who decides maybe that his whole life is wrong so that he ought to go do something else altogether. And really make a completely—a complete reversal. It isn’t just rebellion because rebellion rarely knows what, you know, what it wants to do when it gets through rebelling.

ST: Even if this affirmation against what you…

LH: It’s a little revolutionary.

ST: … what may be considered accepted values, generally—conventional values, let’s say, within a framework…

LH: Yes. Yes.

ST: In many cultures, the mother, the woman, is very strong, you know?

LH: Mmm-hmm.

ST: In Negro families, through the years the mother has always been a sort of pillar of strength, hasn’t she?

LH: Yes. Yes. Those of us who are to any degree students of Negro history think this has something to do with the slave society, of course, where she was allowed, to a certain degree of, not ascendancy, but of at least control of her family, whereas the male was relegated to absolutely nothing—nothing at all. And this has probably been sustained by the sharecropper system in the South and on up into, even, urban Negro life in the North. At least that’s the theory. These women have become the backbone of our people in a very necessary way. This…

ST: Underground Railway leaders.

LH: Yes. Yes. Obviously, the most oppressed group of any oppressed group will be its women, you know? Obviously. Since women, period, are oppressed in society and if you’ve got an oppressed group they’re twice oppressed. So I should imagine that they react accordingly as oppression makes people more militant and so forth and so on—then twice militant, because they’re twice oppressed, so that there’s an assumption of leadership. There was probably a necessity why, among oppressed peoples, the mother will assume a certain kind of, uh, role.

ST: The play, some will ask you, is this autobiographical?

LH: Yes. They keep asking.

ST: Yet, your background is not—your background, culturally, may be the place—to some extent, background—but it is not specifically.

LH: No, it isn’t. I’ve tried to explain this to people. I come from an extremely comfortable background, materially speaking, and, yet, I’ve also tried to explain we live in a ghetto, you know? Which automatically means intimacy with all classes and all kinds of experiences. It’s not any more difficult for me to know the people that I wrote about than it is for me to know members of my family because there is that kind of intimacy. This is one of the things that the American experience has meant to Negroes: we are one people.

I had a reason for choosing this particular class. I guess at this moment the Negro middle class may be from 5 to 6 to 7 percent of our people. The, you know, the comfortable middle class. And I believe that, uh, they are atypical of the more representative experience of Negroes in this country. Therefore, I have to believe that whatever we ultimately achieve, however we ultimately transform our lives, will come from the kind of people that I chose to portray. That, therefore, they are more pertinent, more relevant, more significant, and most important, most decisive in our political history and our political future.

ST: The little girl, if I may, I want to bring up a personal thing: the very charming and alive little sister. Is this slightly autobiographical?

LH: Oh, she’s very autobiographical, because the truth of the matter is that I enjoyed making fun of this girl, who is myself eight years ago, you know? I enjoy making fun of her because I have that kind of confidence about what she represents. I’m not worried about her, you know? Uh, she’s precocious, she’s over outspoken, she’s everything, you know, which, uh, tends to be comic and, you know, people sigh with her and they have one at home like that, you know, and they, they enjoy her for this reason.

ST: She’s very much alive.

LH: Yes.

ST: The African suitor—we come to something now—has always intrigued me very much…

LH: It’s my favorite character.

ST: He’s a remarkable figure. Who is he? What is his meaning in this particular play in contrast to the others?

LH: Hmm. Hmm. He represents two things. He represents, first of all, the true intellectual. The other thing that he represents is much more overt. I was aware that on the Broadway stage they have never seen an African who didn’t have his shoes hanging around his neck, you know, and a bone through his nose or his ears or something.

ST: The stereotype.

LH: And I thought that, even just theatrically speaking, this would most certainly be refreshing, you know. And, uh, again, it required no departure from truth because the only Africans that I have known, of course, have been African students in the United States who this boy is a composite of many of them, as a matter fact, no one guy. And what they have represented to me in life is what this fellow represents in the play. Excuse me. And that is the emergence of an articulate and deeply conscious, uh, colonial intelligentsia. I’m very much concerned and caught up in the movements of the African peoples toward colonial liberation, liberation out of colonialism, and he represents that to me.

In fact, in one sense, he gives the statement of the play, you know? I don’t know how many people get it, but he does. He says… She says to him, “You’re always talking about independence and freedom in Africa, but what about the time when that happens and then you have crooks and petty thieves who come into power, and they’ll do the same things, only now they’ll be Black,” you know? “So what’s the difference?”

And he says to her that this is virtually irrelevant in terms of history. That when that time comes, there will be Nigerians to step out of the shadows and kill the tyrants, just as now they must do away with the British. Uh, and that history always solves its own questions, but you get to first things first. In other words, this man has no illusions at all.

ST: This is a wonderful answer. This, this—

LH: He just believes in the order that things must take. He knows that first, before you can start talking about what’s wrong with independence, get it. And I’m with him.

ST: The New York Times quoted you. You spoke of a certain irritation in seeing plays, so-called plays about the Negro, as such, written by people wholly removed from the situation.

LH: Yes. Yes. The whole concept of the exotic, you know—that in Europe they think that, well, the gypsy is just the most exotic thing that ever walked across the earth is because he’s isolated from the mainstream of European life. So that, obviously, the natural parallel in American life is the Negro, you know, very exotic. So whenever they get ready to do something like a Bizet opera which involves the gypsies of Spain, it’s translated, they think, very neatly into a Negro piece. And I just think this is sort of a bore by now.

Aside from being nauseating, stereotyped notions are also very dull. You know, I think this is said far too—not often enough—that it isn’t only a matter that Porgy and Bess—I’m talking about the book now because once again this is good music, this is beautiful music. I mean this is great American music in which the roots of our native opera are to be found, someday. But the book, the DuBose Heyward book, not only is that offensive, you know, it isn’t only that it insults me because it’s a degrading concept and a degrading way of looking at people, but it’s bad art because it doesn’t tell the truth, and fiction demands the truth. You know? You have to give a many-sided character. In other words, there is no excuse for stereotype. Now I’m not talking socially or politically. I’m talking as an artist now.

ST: Aesthetically now, is what you’re saying.

LH: Exactly. That if someone feels that this is a lie, you know, because it’s just one half of me, then the artist should shudder for reasons other than the NAACP. The responsible artist.

ST: Something you just said: art must tell the truth.

LH: I think so. It’s almost the only place where you can tell it.

ST: What about writing today? Whether it be drama, uh…

LH: There’s a young guy in New York who’s been one of the exiles who’s come home. We’re starting a new movement against the ’30s. Some of the American kids are coming back now from Paris and Rome. Jimmy Baldwin, you know?

ST: Well, he’d gone away.

LH: Who had got—he left. He went. Enough.

ST: Did Baldwin do that, too? Yeah.

LH: Baldwin is who I’m talking about.

ST: Oh, James Baldwin.

LH: James Baldwin. Who is back and who I think—I don’t read novels that much, I’m ashamed to say, for somebody who wants to write one—but I think, from what I read of his essays and some of his fiction, that this is undoubtedly one of the most talented American writers walking around.

ST: Well, I think it’s obvious that it’s no accident that Raisin in the Sun came to be written by Lorraine Hansberry after we’ve been listening to her now. What about success? This little god of success—what does it do to you? It obviously deprives you of privacy to some ex—well, right now it does.

LH: Yeah. It does.

ST: This one moment here.

LH: It does, except that it’s wonderful. It’s wonderful and I’m enjoying it. I think it’s important. I think there comes a time when, you know, you pull the telephone out and you go off and you, you end it. But for the time being I am enjoying every bit of it. I’ve tried to go to everything I was invited to. I shouldn’t even say this on the air, but so far I’ve tried to answer every piece of correspondence I get, which gets to be about 20, 30 pieces a day at this point.

But, uh, this, I don’t have the right to be very personal about the reception to this play because I think the reception to this play transcends what I did or what Sidney Poitier or Lloyd Richards or even Philip Rose or any of us connected with it.

I think what it reflects at this moment is that at this particular moment in our country, as backward and as depressed as I, for instance, am about so much of it, I think there’s a new affirmative political mood and social mood in our country having to do with the fact that people are finally even getting aware that Negroes are tired and it’s time to do something about that question, that… I think we went through eight to 10 years of misery under McCarthy and all that nonsense, and to the great credit of the American people they got rid of it, and they’re feeling like, make new sounds. And I’m glad I was here to make one.

———

EM Narration: A Raisin in the Sun wasn’t Lorraine Hansberry’s final word. As the civil rights movement unfolded, she held America’s oppressive society to account in public appearances, editorials, and a new play.

Lorraine also fell in love, with Dorothy Secules, a politically outspoken blonde 15 years her senior.

In 1963, Lorraine’s health began to fail, and she spent the next two years battling pancreatic cancer. In her final days, two people she loved kept vigil at her bedside: her ex-husband Robert, who would spend the rest of his life devoted to tending Lorraine’s legacy, and Dorothy.

Lorraine died on January 12, 1965.

In a tribute written after Lorraine’s death, the writer James Baldwin noted the toll racial injustice took on his close friend: “It is not at all far-fetched to suspect that what she saw contributed to the strain which killed her, for the effort to which Lorraine was dedicated is more than enough to kill a man.”

Nearly a half-century after Lorraine Hansberry died, her estate released some of her personal papers. One of them was a 1960 datebook entry with lists of her “likes” and “hates.” On her “likes” list were items like “Mahalia Jackson’s music,” “Dorothy Secules’ eyes,” and “that first drink of scotch”; on her “hate” list things like “too much mail” and “my loneliness.” One item made both lists: “my homosexuality.”

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: senior producer Nahanni Rous, co-producer and deputy director Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Jeff Towne, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Denio Lourenco. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman and our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Studios, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season eight of this podcast is produced in association with the Studs Terkel Radio Archive, which is managed by WFMT in partnership with the Chicago History Museum. A very special thank-you to Allison Schein Holmes, Director of Media Archives at WTTW/Chicago PBS and WFMT Chicago for giving us access to Studs Terkel’s treasure trove of interviews. You can find many of them at studsterkel.wfmt.com.

Season eight of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, proud Chicagoans Barbara Levy Kipper and Irwin and Andra Press, the Small Change Foundation, and our listeners, including Damon Evans. Thanks, Damon!

Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. Our website is also where you’ll find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

So long! Until next time!

###