Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis — Chapter 6

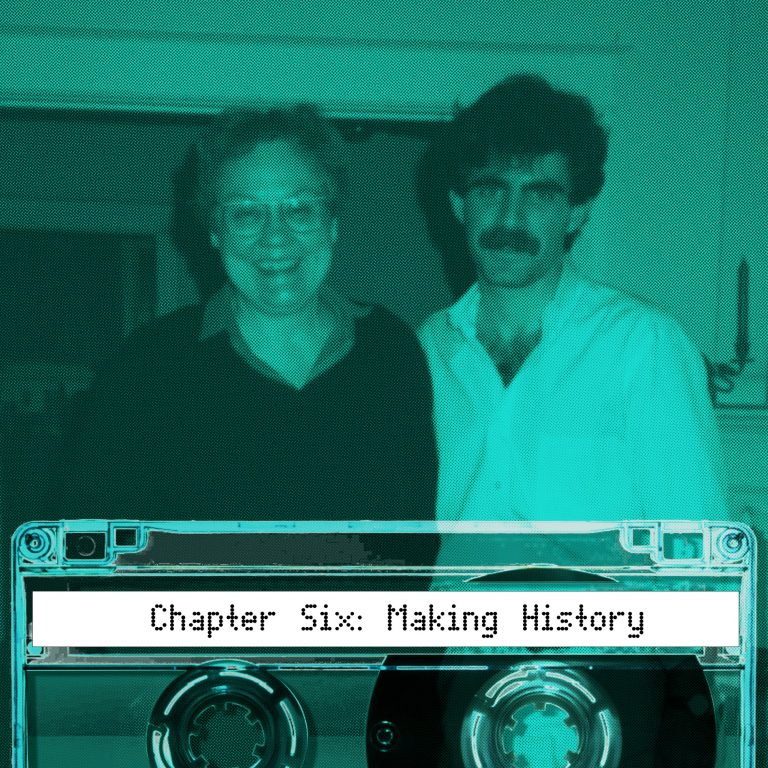

Eric Marcus with Barbara Gittings at the home of Gittings and Kay Lahusen in West Philadelphia, May 17, 1989. Credit: Photo by Kay Lahusen.

Eric Marcus with Barbara Gittings at the home of Gittings and Kay Lahusen in West Philadelphia, May 17, 1989. Credit: Photo by Kay Lahusen.Episode Notes

Being HIV+ was a virtual death sentence. So why get tested? But by 1988 there is a promising, if toxic, drug shown to extend life. Eric and Barry schedule their first test just as Eric starts work on his oral history book about the gay and lesbian civil rights movement.

———

For a comprehensive overview and useful links related to HIV and AIDS, consult this HIV.gov timeline.

For a New York City-specific timeline, see this New York magazine article. (Please note, however, that the Patient Zero theory referenced at the top has since been discredited; for more information on the subject, watch the documentary Killing Patient Zero.)

This chapter covers the fall of 1988 to June 1992. During that time, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 158,247 new cases of AIDS were reported, in addition to 113,904 deaths. This brought the cumulative totals to 253,448 reported cases and 171,890 deaths in the United States. Although a blood test for HIV was available by this time, the actual numbers remain unknown.

In the episode, Eric and his then partner, Barry, are finally ready to get tested for HIV. Like many others, they had been waiting until there was a sliver of hope, a clinically proven treatment that would buy them time should they get sick. That sliver of hope came in the form of a drug called AZT, although AZT was controversial from the beginning. Many publicly questioned and condemned the drug because of its potentially deadly side effects and limited efficacy, but it remained the only AIDS drug that the FDA approved (in March 1987) until the arrival of the life-saving protease inhibitors in the mid-1990s.

In 1989, prophylactic agents to prevent pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), a common and deadly opportunistic infection, were officially recommended for people with AIDS. By then, 30,534 Americans had already died of AIDS-related PCP, and the widespread use of interventions that could prevent the disease encouraged people to get tested earlier. The message in the gay community was clear: early detection could save your life.

Eric and Barry chose to get tested anonymously; after all, if you tested positive and your HIV status became known, you were faced with potential discrimination in housing, employment, and health care. Despite that very real fear, New York City had only a few anonymous testing centers back then. Moreover, there were no rapid tests in 1988, so Eric and Barry had to wait three long weeks for their results. You can do a deep dive into how HIV tests have changed over time here.

The technology to produce commercial at-home tests existed as early as 1987, but that path was blocked by the government because of concerns about accuracy and insufficient counseling. Empathetic social workers like Solveig, the counselor assigned to Eric, were deemed essential to educate the public and help combat the stigma of a positive result.

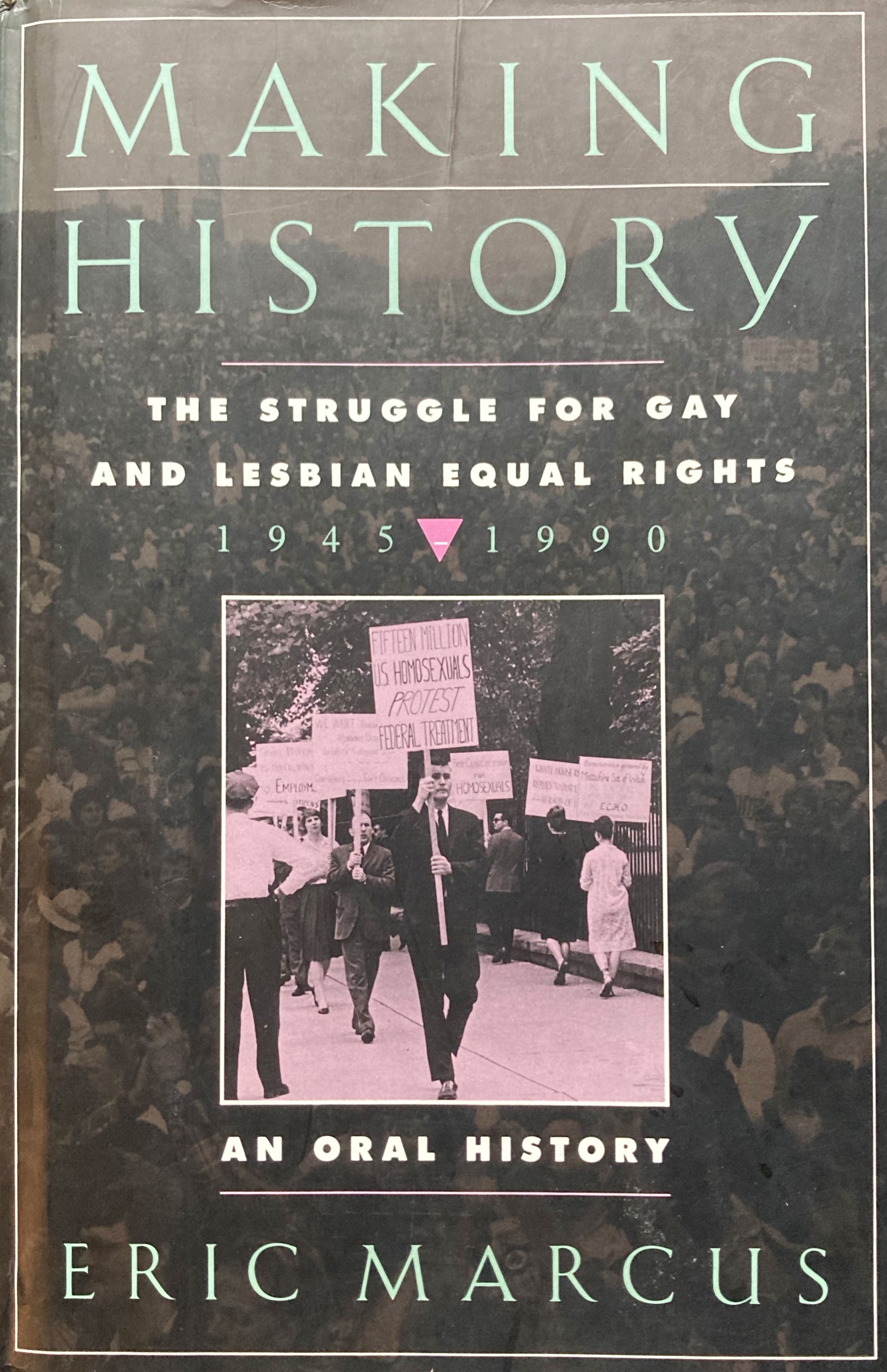

After testing negative, Eric set about doing interviews for his book Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945-1990 (revised and reissued in 2002 under the title Making Gay History). In 1992, the book was published to rave reviews, e.g., in the Los Angeles Times, Newsweek, and the Bay Area Reporter. Making History was also featured on the front page of the New York Times Book Review along with Lillian Faderman’s Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers. During his book tour, Eric was interviewed by the legendary Studs Terkel (listen here), and he returned to Good Morning America for a conversation with Charlie Gibson (watch it here).

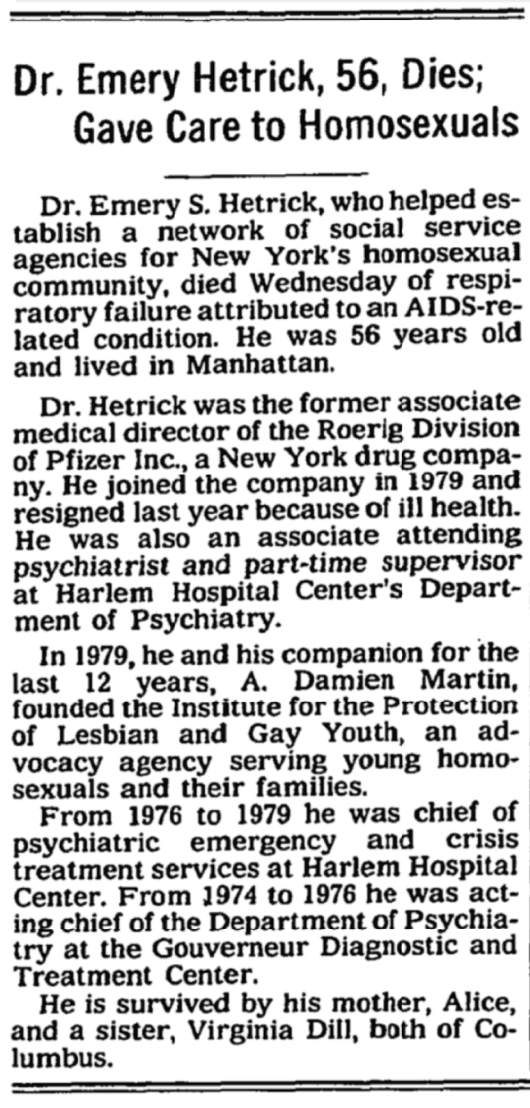

The episode includes the voices of four activists Eric interviewed for Making History who died from AIDS-related complications before the book’s publication. They each have an individual Making Gay History episode devoted to them. Click on the links to hear their stories and find out more about their lives and legacies in the accompanying episode notes: Dr. Damien Martin, cofounder of the Hetrick-Martin Institute; author Vito Russo, who cofounded GLAAD and ACT UP; Morty Manford, who with his mother, Jeanne Manford, cofounded PFLAG; and Tom Cassidy, the CNN anchor who made his diagnosis public in a local New York City CBS TV news series.

The four men are memorialized in one or more panels of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. During the fall of 1988, the quilt returned to Washington, DC, with 8,288 panels, having tripled in size since its inaugural display on the National Mall a year before. Today, the quilt has 50,000 panels, which you can view and search here. Other moving efforts to remember those lost to the AIDS crisis include the AIDS Memorial on Instagram and Robert John Quinn’s Memorial Books, which contain more than 7,000 obituaries clipped and saved between 1983 and 2000.

Due to structural racism and injustice in the United States, AIDS continues to disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minorities. Forty years after the New York Times first reported on the disease, the AIDS crisis is ongoing.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and in this season of Making Gay History I’ve been revisiting my past to tell you about the early years of the AIDS crisis—when I was coming out and coming of age as people around me were getting sick and dying. I’ve returned to memories from the 1980s, trying to reconstruct what happened. Because it turns out it’s part of our LGBTQ history and because ultimately it’s the story behind Making Gay History, and how and why it came about.

This is our sixth and final chapter: “Making History.”

———

Announcer: KABC TalkRadio 790.

Michael Jackson: This is TalkRadio, I’m Michael Jackson. I want to turn immediately to Eric Marcus, the author of The Male Couple’s Guide to Living Together. We’re speaking with homosexual males who, who are couples…

———

EM Narration: Throughout 1988, I crisscrossed the country promoting The Male Couple’s Guide, with appearances on local TV, CNN, and a lot of talk radio shows, where the calls ranged from hateful to heartfelt.

———

MJ: Hi, John.

Caller 1: Hi.

MJ: Yes, Sir.

Caller 1: I was calling to tell you that we met—my lover and I—in 1956. We’ve been together since.

Eric Marcus: Wonderful.

MJ: Thirty-two years.

Caller 1: Yeah, we’ve had a lot, a lot—in the early ’50s, the late ’50s, early ’60s, and into the first part of the ’70s—a lot of legal problems when it comes to buying and purchasing properties, uh, that sort of thing. And then they passed the law, you know, where singles could buy. And then we were able to buy our first property.

MJ: So starting now would be a considerably easier situation for you than it was then.

Caller 1: Yes, well, I don’t know with this AIDS scare, everybody’s starting to, you know, to, uh, to wear the mask and, uh, you know, burn the crosses again.

———

Peter Boyles: Good morning, you’re on The Talk of the Rockies with Peter Boyles. Our guest is Eric Marcus, the book The Male Couple’s Guide to Living Together.

Caller 2: Uh, good morning, Peter. Um, I’d just like to say, uh, I’m getting tired of hearing the old cop-out about, uh, they were born gay and they’ve always been that way. I think it’s just like with alcohol or drugs or any other bad habits, they’ve just gone ahead and got worse and worse, and they end up in the gay lifestyle. I’ve lived in San Francisco for three years, and, uh, me and my wife and children shared a flat with five drag queens. I’ve been to the hardcore gay bars there, and they’re lucky that the only disease they have is AIDS.

EM: You’ll have to, you’ll have to give me a tour—this is Eric Marcus speaking—you’ll have to give me a tour of the hardcore bars sometime because I haven’t been… Um, first of all, uh, let me ask you a question.

Caller 2: Okay.

EM: Um, were you born heterosexual?

Caller 2: Um, I would say yes.

EM: Okay. If you can be born heterosexual, could it have been possible for you to be, to have been born homosexual?

Caller 2: I don’t think so.

PB: Bob, do you believe that there have always been homosexuals?

Caller 2: Well, sure, since Sodom and Gomorrah, of course.

PB: Okay, alright. Well, let’s say since Sodom and Gomorrah there’s always been homosexuals. But, but why do you think that happens? Do you think that it’s, it’s an act of the devil that Eric Marcus likes to make love to his, his boyfriend?

Caller 2: I think it’s because of a psychological, uh, aberration.

EM: Actually, I wish I had more time to, to spend physical time with my boyfriend, uh…

———

EM Narration: It had happened. I was officially a professional homosexual. I had resisted the idea for a long time, but I found I was pretty good at handling homophobic callers and prudish radio hosts.

Before heading out on the book tour, I really thought I’d be out there talking about male couple life, like a gay Dr. Ruth, but the questions turned out to be much more basic. They couldn’t quite get over the fact of my sexuality: asking how I became gay, how my parents reacted, callers telling me that people like me were mentally ill or morally wrong—and, of course, questions about AIDS were never very far away.

———

PB: Can I ask you a, a personal question?

EM: Go ahead.

PB: Um, Eric Marcus is a gay male. Do you ever think that the time bomb might be there?

EM: All the time.

PB: You’d have to.

EM: And, uh, my partner and I have not been tested. We’ve been together fi—nearly five years. Uh, because of the incubation period, either of us could potentially develop a disease.

PB: I know this is away from the book, and I, I don’t mean to break it away from the book, but when I see the thrust and the commercials and the PSAs to test and to be safe and to find out… I’ve heard this, and I can’t—this is empirical rather than statistical—that more straight people are getting tested for AIDS now than gay people.

EM: Oh, if I were straight, I wouldn’t be afraid of being tested. The odds of testing positive… If I were pretty sure that I’d test negative, I’d go out and get it now, just as a little insurance…

PB: Peace of mind.

EM: … peace of mind. But growing up when I did, in a place like New York City, the odds are probably 50, 50 or better, that I could test positive. And that’s too—the odds aren’t good enough for me to go out and get tested. Uh, it’s a little too frightening.

PB: Why would you not be tested? You said neither you nor your partner would be tested.

EM: There’s, there’s a battle back and forth on that point. The fallout from finding out that you’re positive, HIV positive, is, is so damaging so often that we decided it’s easier to live with the thought in the back, backs of our minds, that we are negative and practice safe sex than to live knowing that we were positive.

———

EM Narration: The back and forth between me and Barry about whether to get tested came to an end in the fall of 1988. That was three years after the first HIV test became available, and within a month of the publication of a new study in Scientific American about the drug AZT. The study confirmed that AZT was extending the lives of people with AIDS by a few months. Up until that time there had been no clinically proven treatment.

I confide in my Aunt Mynette and Uncle Richie that Barry and I are getting tested. If the worst comes to pass, I want time to absorb that reality before having to tell anyone else. It turns out that I also talked to my sister, Heidi.

———

EM: During the AIDS crisis, did you ever have a concern about me?

Heidi Katz: Yeah. I worried, I really worried. And, uh, I remember there was a time in particular where you were very scared. That got me worried, when you worried.

EM: Uh-huh. We talked about it?

HK: Yeah. You told me you were going for a test and how worried you were. I think that someone that you were having a relationship with had tested positive.

EM: I talked more than I thought I had. Yeah, um, it was a guy, it was a guy that Mom set me up with.

HK: Oh yeah, that’s right—that guy, Bob or somebody.

EM: Yes. Yes. It was Bob.

HK: Yeah.

EM: Yeah. Um, in 1981. And I don’t remember his last name, I don’t remember his mom’s name, but his—Mom, our mom and his mom met, and it was two Jewish mothers who decided to set their sons up.

HK: That’s funny.

EM: Yeah. And then Mom called me, like, months after Bob and I had gone on a couple of dates that, that went well beyond dinner. And she asked me if I’d heard from Bob. And I said I hadn’t. And I asked her why. And she said, “Well, he’s in the hospital with that new gay disease.”

HK: Yeah.

EM: So that was from—yeah. So that was… So I didn’t realize I told you that before I went in to get tested.

HK: Yeah. Yeah. Like, you were really worried, like on pins and needles.

———

EM Narration: It’s been seven years since I was first knowingly exposed to HIV. And I could easily have been infected by any number of other guys in the interim, including Barry, before safer sex was even invented. Given the often long incubation period for developing full-blown AIDS, there’s every possibility that I am a ticking time bomb and just don’t know it.

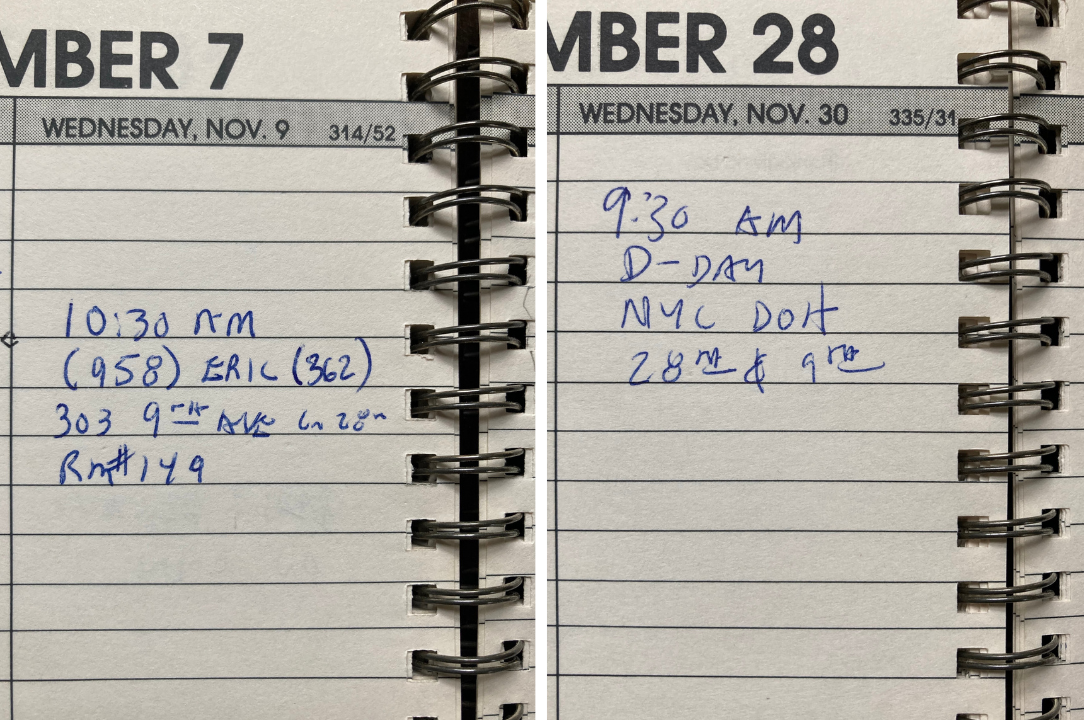

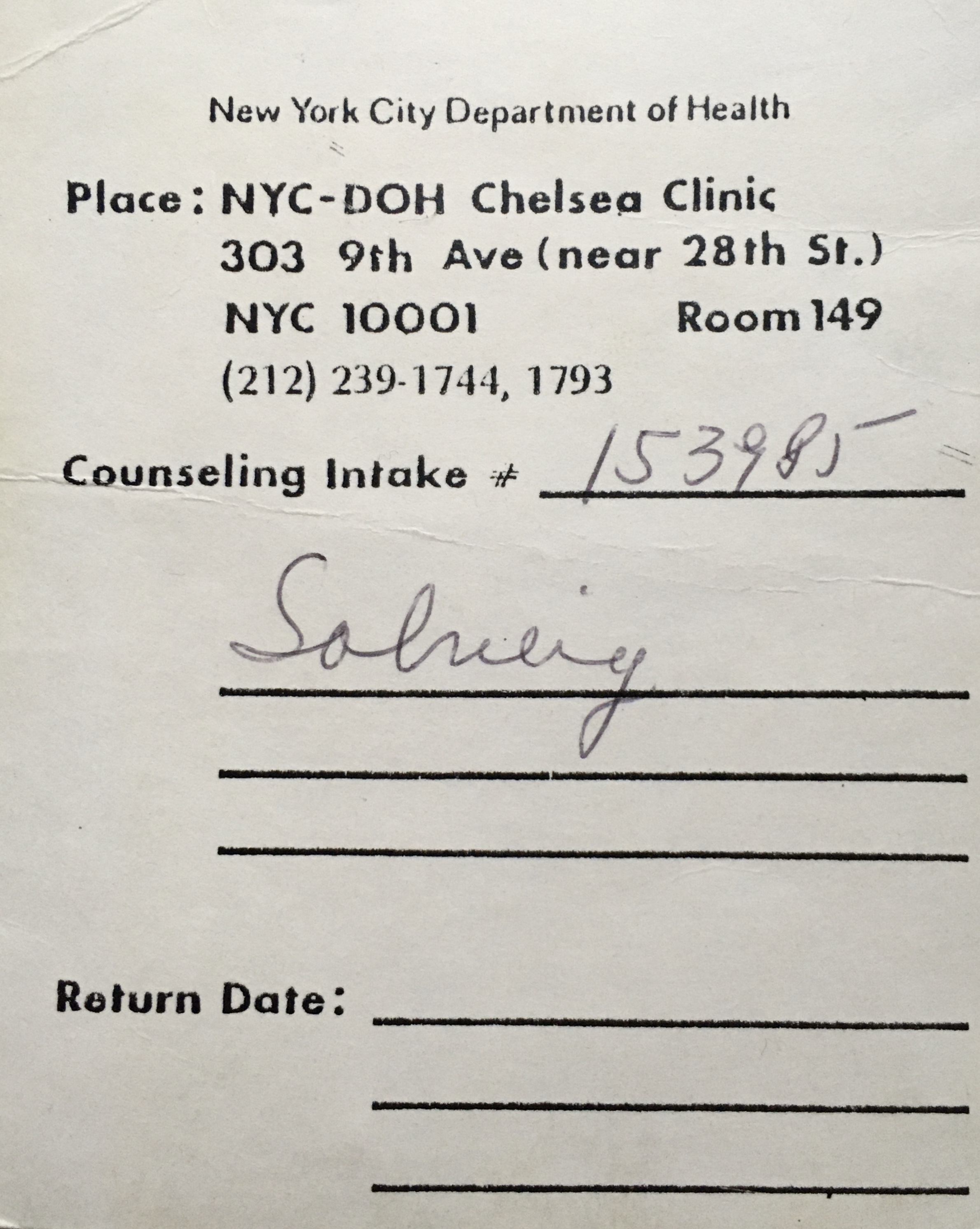

Barry and I decide to get an anonymous test instead of going to our doctor. We don’t want to risk anyone finding out. The stigma and potential discrimination associated with AIDS could mean losing your job, your insurance. I call to make an appointment for us downtown at the city’s public health clinic in Chelsea. I’m number 958 and Barry is 362. November 9, 10:30 a.m.

Just a couple of weeks before, I’d signed the contract to write my second book, an oral history about the gay and lesbian civil rights movement. I’ve been trying really hard not to think about what testing positive could mean for that book. It’s due on my editor’s desk in two years. I’ve watched too many friends waste away and die in much less time than that. So many unfinished books. Unfinished lives.

Barry and I step through the door of the Chelsea clinic into an overheated lobby waiting room that’s filled with people sitting in rows of attached greenish blue plastic chairs. The air is thick. I feel faint. We’re lucky to grab a couple of empty seats and wait for our numbers to be called. An hour later, blood drawn, Band-Aids on arms, we’re out the door with an appointment to return for our results in three weeks.

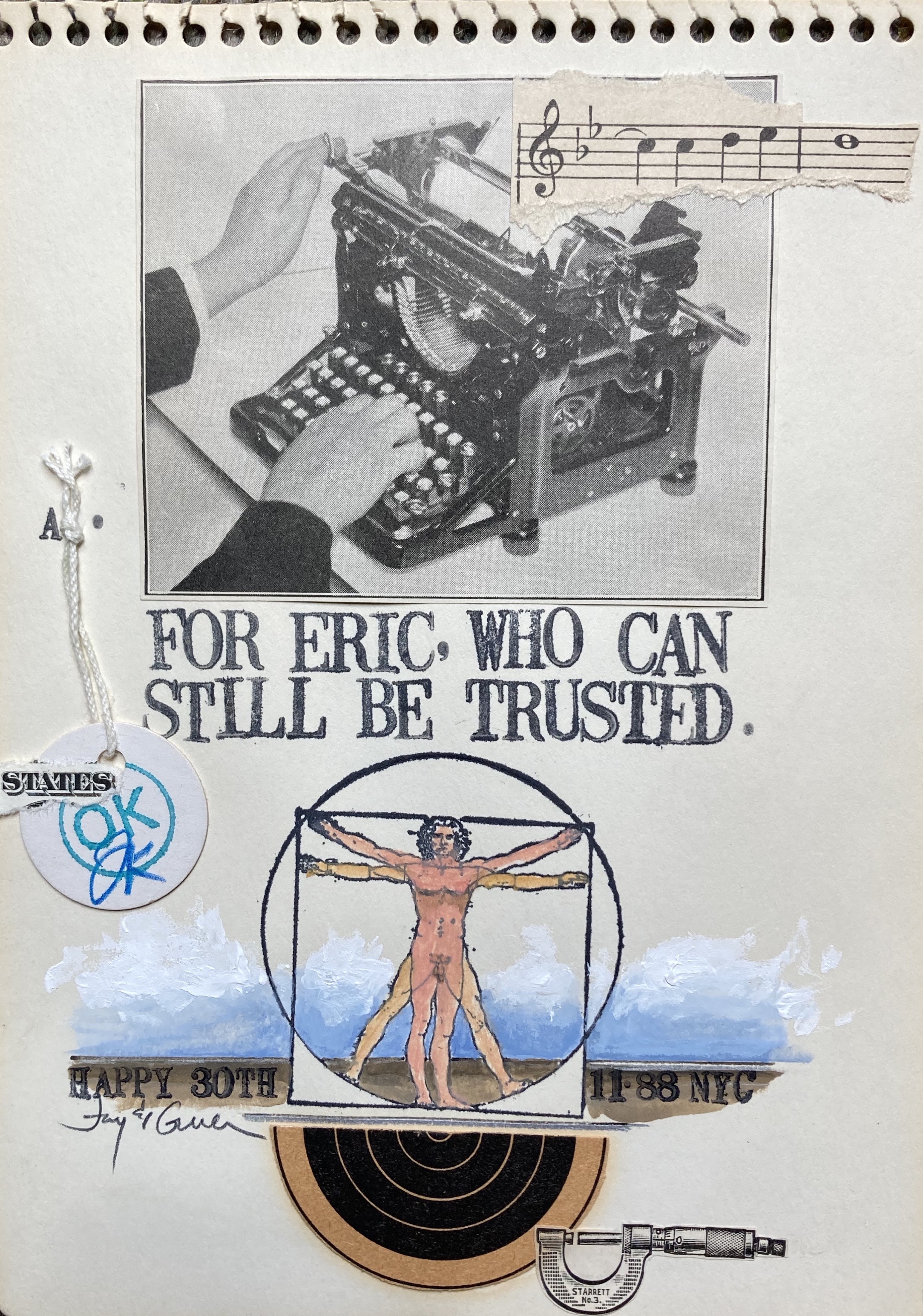

Barry heads back to the office. I return to my desk at home. Time turns to sludge for the next 21 days. Slow and viscous, despite joyful distractions. Barry threw me a seemingly carefree 30th birthday party—all friends, no family. And then we spent Thanksgiving with family, no friends. Still, those three weeks felt like a year.

———

Solveig Simonsen: I’m Solveig and I worked for the Department of Health in Chelsea, New York City. My job title was Counseling & Testing. People would come in and get counseling and get tested. And it was also, uh, taking information on what their risk factor was. Um, so my day was kind of filled with giving results, which was very difficult at times. Um, god, it’s so hard to go back there because you almost don’t want to—you know, a lot of sobbing, a lot of crying, a lot of, a lot of hand-holding, a lot of, um… Especially pregnant women was really difficult. People needed us—they were discriminated against, their families, you know, threw them out—they had no one but us.

I came from the mindset of, this is not a death sentence. I never looked at it that way. I looked at it like, there are things you can do, you know, you have to now pay attention to your health—your, your physical, your spiritual, everything. Because that’s all we had. We didn’t have anything else.

———

EM Narration: D-Day. November 30, 1988, 9:30 a.m. Barry and I are back at the Chelsea clinic, waiting in the greenish-blue plastic chairs. Our numbers are called and we’re met by two social workers.

———

EM: Barry and I couldn’t, they wouldn’t see us together. We wanted to be taken in together. We weren’t married—we couldn’t be married—so we were sent with separate people, and I was assigned to you.

———

EM Narration: The petite blonde woman clutching the file containing my results was Solveig.

———

SS: My goodness, 33 years ago!

EM: That’s all. It’s like yesterday, Solveig.

SS: Oh, my goodness, Eric.

EM: Let me tell you, tell you the story of how it unfolded and see if you remember anything. So I remember going into your office. Um, you smiled, um, you showed me, indicated where I should sit, and I sat next to your desk. You had the file on your desk. You opened the file. And as you were doing this—it was like a movie to me because suddenly I couldn’t hear anything except the blood rushing through my ears and my heart pounding. And the color left the room. It was, it was, um, uh, it was, uh, it was terrifying.

And you opened the file—I can see you opening the file—and you looked down and you smiled and you looked up at me. And you said, “You’re negative.” And I almost fainted. Um, the sound came rushing back, the color came back into the room. And I didn’t cry, but I was, I was giddy.

And then I thought, oh my god, what about Barry? Because he was in another room in the building getting his test results. So I—you, you, you gave me some information about, about how to stay negative. Uh, you had handed me, um, a little slip of paper. Um, it said “Solveig”…

SS: Yeah, I know, and it was written by me. It was my handwriting.

EM: So it said “Solveig” and it had my number, because it was anonymous testing. Um, and I thanked you and you wished me well, and I left your office and went down the hall back to the lobby.

And there were lots of people sitting in plastic chairs, and then there was Barry. We’re standing there. We don’t know what each other’s results are. And we start giggling. And that’s when we realized we were both negative. But then there you were over my shoulder and you said to us, “Come with me.” And Barry said, “Why?” And I said to Barry, “I don’t know why she wants us to go down the hallway, but whatever she wants, let’s just do it.”

And so, so you took us down the hallway looking for an empty room and there was none. You took us to the end of the hall. You took each of our, you took each of our hands and held our hands. And you said, “I deliver terrible news every day, all day. And I just want to share—I just want to share in a moment of happiness with you.”

That’s why I’ve remembered you all these years. That’s why I saved that little slip of paper and put it with my birth certificate and my old passport, because, um, because of that moment. It was so human of you. And so, um, beautiful, um, and so meaningful. And I’ve never forgotten you.

SS: Wow. Thank you for sharing that. I, I don’t remember that, but I’m so glad that I did that. I am so grateful for all the people like yourself that I tested and, and, um, that I had the opportunity to connect with. I am the lucky one because I saw people work so hard. Like, if somebody was positive and, like, I get like, even being negative, I gave you the same information. “This is what you need to do. You need to do this, this, and this. And it’s about your health. And it’s about, you know, your wellbeing. You, you need to, like,” you know…

I feel privileged that you allowed me—it’s such a vulnerable thing… I mean, it’s intimate. It is, it is…

EM: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, standing in that hallway with you, with you holding our hands, it couldn’t have been more intimate.

SS: Yeah. Yeah. And, and letting me into your lives, you know, giving all this information that I’m asking behind closed doors, you don’t know me, and, and being able to be vulnerable to, to, to tell me, to talk to me.

EM: Yeah, well, I got lucky that I got you.

SS: And I was lucky I got you. I’m just, like, blown away by this whole thing.

———

EM Narration: Reconnecting after more than 30 years—thanks to a social media search sparked by that slip of paper I’d saved all these years—brought even more memories flooding back.

———

EM: And then we stepped, went out on the street and I had told my aunt that I, that I was getting tested. And we were on the corner of 29th and Ninth Avenue. And there was a, a phone booth directly across the street. And I said, “Barry, we need to get to that phone booth.” And he stepped off the curb into traffic without seeing that there were cars coming, and it was against the light. And I grabbed him and pulled him back. And we were thinking, oh my god, we just got tested, we found out we’re negative, and you’re gonna get killed because you weren’t paying attention to the light. And it’s my fault because I told you we have to get to that phone booth.

We get to the phone booth, and I called my aunt and told her. After she said, “Thank god,” she said, “Have you called your grandmother?” And I said, “Why?” And she said, “Call your grandmother.” And it turns out—I just talked to my aunt about this the other day—she said—and I’d come out to my grandmother, uh, not that long before that, several months before that—she said, “It’s all she talked about. She was just so worried that you would get sick and die.” And she’d never said anything.

So the next phone call from that phone booth was to my grandmother to tell her that we were HIV negative.

———

EM Narration: Every aspect of that day is seared into my memory. But for Solveig, I was just one of the many people she counseled or supported over decades of work in HIV/AIDS.

———

EM: You saw hundreds and hundreds of people, but I wanted you to know, um, how much meaning that had for me. Um, and it made me—I could live my life, um, I wasn’t gonna die from this. And I assumed you wouldn’t know who I was, but you, you, um, have stayed with me all of these years.

SS: We never know, you know, like, how we affect people or what… We don’t ever know how fortunate I am to know that I did something that was meaningful.

EM: It was so meaningful. Um, but it’s such a, it’s such a vivid, um, pivotal moment in my life, and you were there, and I’m grateful to you for that.

SS: I’m so grateful. Now I don’t ever want to let you go, I wanna [inaudible] forever.

———

EM Narration: With the HIV test behind me, the terror that had been a constant hum for seven years turned down several notches, and I could turn my full attention to my oral history book. I had very grand plans for how I was going to write my book. I’d do 250 interviews across the country, choose the best 40 or 50, and use those oral histories to tell the story of the lesbian and gay civil rights movement from around World War II until 1990. I first had to build a timeline of the movement because none existed. That meant lots of hands-on research, poring over old magazines and the two available books on gay history. And at the same time I had to start doing interviews because the clock was ticking. And it wasn’t just my two-year deadline. There were men with AIDS and old people I wanted to interview whose time was running out. I made lists, filled out index cards, cross-referenced everything, made interview appointments, flight reservations, and arranged to sleep on friends’ couches in cities across the country.

I had the sense that these were important interviews and I figured someday someone might want to use them for something—I didn’t know what. So I asked my former boss at CBS for advice. He used to work for National Public Radio and I ask what equipment his colleagues use, and then I go out and buy it.

———

EM: Interview with Wendell Sayers, Saturday, January 14, 1989.

Interview with Jeanne Manford and Morty Manford on Saturday, May 13, 1989.

Interview with Chuck Rowland, Tuesday, August 22, 1989.

Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Location is the home of Dr. Hooker in Los Angeles, California.

Tape one, side one.

———

EM Narration: Very quickly I could hear that the stories I was collecting, the lives I was recording, were precious. And even though I wasn’t going to die from AIDS, I began to worry that something else would happen to me along the way and I wouldn’t get to finish the book. A plane crash. Car accident. A coronary.

I was also afraid that something would happen to the tapes, so as soon as I got home from an interview I’d make a duplicate and I stored the dupes in a separate, secure location. And once I was well into the project, every time I set out on another trip, I’d write a letter to my editor and tell him where I was in the project so he could hire another writer if something happened to me. I put the letter and a set of diskettes with the latest files in a padded envelope and FedExed the whole thing back to New York.

By then, Barry and I had moved to Barry’s home state of California, to San Francisco. I did almost nothing but work—between the book and freelance writing gigs to help cover my expenses.

Once I’d recorded 89 interviews I realized that if I didn’t stop and start transcribing, I wouldn’t have enough time to edit the interviews and write the book. Since I had a limited budget, I did all my own transcriptions of the hundreds of hours of tape and wound up with such a bad case of tendonitis in both wrists that I had to wrap them in Ace bandages every night so I could sleep.

The book wasn’t about the AIDS crisis, but there was no way of writing a book like this, at the end of the 1980s, without the epidemic’s influence and consequences rising through the voices of so many of the book’s subjects and onto its pages.

———

EM: Interview with Damien Martin. Saturday, December 11, 1988. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Location is the home of Damien Martin in New York City. Tape one, side one.

———

EM Narration: One of the first interviews I scheduled in late 1988 was with Damien Martin, Dr. Emery Hetrick’s surviving partner. Emery had died from complications of AIDS in 1987, Damien was ill. In the late ’70s, Damien and Emery had cofounded a radical, groundbreaking organization called the Institute for the Protection of Lesbian and Gay Youth, an institute that continues today as HMI, the Hetrick-Martin Institute. Sitting with Damien in December of 1988 I asked him what it was like to go on without his partner at his side.

———

Damien Martin: Three months before, uh, Emery died, I was diagnosed with AIDS. And, um, poor baby, I remember he was upset on a number of levels, but the major one was, “Who’s gonna take care of you, you know, like you’ve taken care of me?” And in one way it was easy for me because he was so much sicker that my illness sort of didn’t have much reality.

Um, I think the main reason I was able to handle it was because I really thought I was gonna die very soon, so it didn’t matter that much. So what I did was I just got even more involved in the institute with the idea of, um, getting things ready for when I was gonna leave. To, um, you know, just—that there would be an organization that would be strong enough that could survive the loss of the two of us and that would go on. Because, uh, well, this may sound corny, but I think the institution is much more important than any of us.

Uh, plus, I also felt as though I was working with Emery. And so in a way there it, it helped me with my grief, uh, in the sense that, uh, it was not like I had lost everything—we still were working together.

And, uh, I must admit I have difficulties. I usually just don’t think about death anymore. But every once in a while it’ll come. It’ll come in various ways. I’ll, uh—you’re buying a suit and I’ll think, what the hell are you buying a suit for, you’ll probably be dead in six months. And I’ll think, well, so you’ll be a well-dressed corpse, and I’ll, I’ll buy the suit.

EM: So the end doesn’t frighten you.

DM: No.

EM: Cause you’ve already started…

DM: Right.

EM: Yeah.

———

EM: Interview with Vito Russo. Wednesday, December 21, 1988. Location is Vito Russo’s home in New York City. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

———

EM Narration: Also at the top of my list was Vito Russo. He was a legendary change-maker. Vito shook up the film industry with his 1981 book, The Celluloid Closet, which was about how Hollywood’s bigoted portrayal of gay men and lesbians helped shape public opinion about homosexuals. Vito cofounded GLAAD, a media watchdog organization originally called the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation.

He also cofounded ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. Vito had been entwined with the gay rights movement in New York for decades, and had lost so many loved ones to AIDS, including his boyfriend, Jeffrey, who had died in March 1986.

———

Vito Russo: He’s been gone almost three years now and I’m still sick and I’m very lonely. You know, it’s hard to live alone and be sick alone. And as many of your friends as you have—and I have good, loving friends and a great support system—people cannot be sick for you, and they can’t suffer for you, and they can’t be with you all the time.

Gay life is very interesting now because we’ve divided into the positives and the negatives in some cases. And it’s difficult to meet people. Then, on top of that, you meet somebody who likes you or whatever, and then you have to deal with the fact that you’re sick, and you have to tell them that, and you have to hope that they can handle it. I mean, you know, who the hell is gonna get into a relationship with somebody who is probably gonna die soon? You know, they don’t want to put themselves through that.

EM: Because it’s so painful.

VR: Because it is so terribly painful. I know how painful it is. I’ve lost too many people. It’s really astonishing when you look back on it and you think, most of the people who were my friends are dead. Most of my friends are dead. And at this age that shouldn’t be.

EM: You’re only 42.

VR: Yeah. It’s not natural by any definition of the word natural.

EM: The images I’ve seen of you in the last couple of years—when I’ve seen you on television—I’ve seen you in a very, very activist role. So it’s been, has it been AIDS then that’s propelled you…?

VR: Yeah, it has. It has. I mean, I was, uh, one of the people, um, who, along with Larry Kramer and Vivian Shapiro and Tim Sweeney and a couple of other people, who founded ACT UP, which became a whole new phase of activism, not only for me, but for the community in general. And it’s a new kind of activism, because it’s created a coalition. ACT UP is composed of gay people and straight people, women and men, Black and white, you know, and all these people have one thing in common and that is they want to put an end to the AIDS crisis by, you know, any means possible.

———

EM Narration: On October 8, 1990, I interviewed CNN business anchor Tom Cassidy.

———

EM: Office of Tom Cassidy at CNN in New York City. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

———

EM Narration: Tom got to be one of the first openly gay national news correspondents. Not because he’d intended to be, but because his AIDS diagnosis forced him out of the closet. He decided to use his diagnosis as a way of educating the public, when CBS in New York approached him about a special series.

———

Tom Cassidy: “Would you agree to participate in a story, a series, that we want to do about AIDS through your eyes?” And AIDS was turning 10 years old in CBS’s eyes. They wanted to look at the plague through my eyes.

EM: Ten years later.

TC: Yeah. And, uh, I gave them a very—I didn’t even blink. I just said… And that kind of threw him because he thought he was gonna have to sell me on it. And I said, “Sure.”

EM: Why did you say, “Sure”? Because that meant coming out about having AIDS, publicly, and about being gay.

TC: I wanted to do some good.

EM: What could you do?

TC: Uh, make AIDS patients feel better. Make the public understand that some of their TV newsmen are gay and sick. Uh, everyone identified me as one of the, the “good guys,” and there are millions of people that have seen me on television. And I wanted them to know that a favorite of theirs could get this disease. And, and secondarily, he happened to be gay.

EM: What would that show them? What would that show…?

TC: That AIDS is a much—it’s not just a gay problem. When, when, um, gay people die of AIDS, the society is so much poorer. Because in a lot of ways, uh, gay people, um, are the spice of life. Life isn’t as much fun in this country after losing 85,000 very creative, uh, well-intentioned, funny, um, productive people in the primes of their lives. And the straight world sort of knew it but they really needed to have it mapped out right in their face.

I didn’t think I had anything to lose by trying it. I guess I really wanted to make a political statement…

EM: As…?

TC: … a gay person as well as an AIDS patient.

———

EM Narration: Damien Martin, Vito Russo, and Tom Cassidy. All three men would be dead before my book was published.

And then there was Morty Manford. I always identified so strongly with him. A couple of gay Jews from Queens who wanted to make the world a better place for people like us. Morty and his mother, Jeanne, had cofounded an organization for parents of gay people back in 1972 that’s now called PFLAG. Morty had also been the president of the Gay Activists Alliance and a major leader in the post-Stonewall gay liberation phase of the movement in New York City.

———

EM: Interview with Morty Manford. Tape two, side one.

———

EM Narration: I talked to Morty over two visits. I had the sense he wasn’t well, but skirted the issue of AIDS right up until the very end of our last session together.

———

EM: I think the component in all of this is anger, and even more deeply felt now because of AIDS, because people have died.

Morty Manford: People are hurt. You see your friends all around you dying.

EM: Has that had a significant impact for you?

MM: Yeah, I guess it has.

EM: Is this something I shouldn’t ask?

MM: It affects all of us. I mean, it’s, it’s, it’s devastating.

EM: But what about you, I mean, in terms of your friends? Have you had friends…?

MM: Yeah, yeah. We all have, haven’t we?

EM: Yeah. Uh, my lover’s fine. Um, my best friend’s lover has AIDS. So it’s that close, but it hasn’t… Uh, we went and got tested last year. Both were shocked by the, the results. Um, he came out in San Francisco, I came out in New York, and the statistics were not in my favor. Um, I still thank god every morning because the statist—given the statistics, I should not, I shouldn’t even be alive given where I was and what I did.

MM: Well, what have we lost, 65,000 people so far? And, uh, a million of us—million of us, it’s not all gays, but, uh—a million people they say are infected now. I mean, it’s, it’s just impossible to grasp that…

EM: Do you ever wonder what would have happened if not for the work you and many others did in the late ’60s and early ’70s, if AIDS had happened in pre-1970 times?

MM: Well, put in terms of the gay movement, if there hadn’t been a movement we would be ill-prepared… Not that, uh, we’ve had, uh, the kind of resources we should have to deal with it today, but at least we’ve got our own infrastructure that’s been there to resist and press for greater resources.

You know, a few years ago, when the hysteria was much greater, we had these lunatics calling for, uh, uh, gays or people infected with AIDS to be put in a concentration camp kind of setting. And there was some popularity to that idea. There’s no telling what would have been—and in this context, given the enormous fear and devastation of the disease—but for the movement and all those wonderful people out there and, and, you know, the gay organizations and, and, and social service outfits and political groups, we’ve been pretty horrendous.

I think the, uh, existence of the AIDS crisis has given a lot of bigots fodder. They’ve used the AIDS issue to camouflage their prejudice or to justify it. But I think, I think, I think we’ve done pretty good in, uh, at least holding, you know, back that, that, uh, pressure to, uh, backtrack.

Eh, I’m, you know, not being terribly articulate—last time we spoke, it was, it was in the morning and…

EM: You’re being just as articulate, you just don’t…

MM: No, I’m not, I’m, I’m, I’m…

EM: … fading…

MM: … grasping for words and…

EM: It’s okay. I can edit just the same. Thank you. Anything you want to add?

MM: On your next trip to New York, if, uh, I think of something else, uh, I’m sure we’ll…

———

EM Narration: It wasn’t until years later that I discovered Morty had been diagnosed just a couple of weeks before that conversation. Like Damien, Vito, and Tom, Morty didn’t live long enough to see his story in print.

A few months before the book was set to be published, Jeanne Manford called to tell me that her son was dying. She said Morty was upset that so many of the movement’s triumphs, the untold stories of the fight for gay liberation, might be lost with the deaths of people like him. He feared they’d be forgotten, that he’d be forgotten. I sent Jeanne the pre-publication manuscript of the book so she could read Morty’s chapter aloud to him. He was home, extremely frail, and no longer able to read it for himself. Morty died on May 14, 1992. He was 41.

The first edition of Making Gay History, which was called Making History, was published two and a half weeks after Morty’s death.

Postscript. Morty Manford, Damien Martin, Vito Russo, and Tom Cassidy were just four of the seven people I interviewed for the book who would ultimately die of complications from AIDS.

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that there were effective, life-saving treatments for HIV/AIDS. And 40 years after that first New York Times headline about a rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals, there’s still no vaccine.

In 2019, the most recent year for which U.S. statistics are available, there were approximately 35,000 new HIV infections; 1.2 million people were living with HIV. Around 5,200 died from AIDS-related causes.

And worldwide in 2020, approximately 37 million people were living with HIV; 680,000 died from AIDS-related illnesses. Globally, since the start of the epidemic, AIDS has cost 36 million people their lives.

If you look at the dedication page at the front of that first 1992 edition of Making History, you’ll see that I dedicated the book to three people: my grandmother, because she was my rock and paid for the computer on which I wrote it. My mother, because my grandmother said that to keep the peace I couldn’t dedicate the book to her unless I included my mother, and put her first. As ever, Grandma May was right. And I dedicated it to Homer—that was my nickname for Barry—because his fingerprints are on almost every page of the book. I couldn’t begin to count the number of times I asked him to read something, edit a passage, or to offer his advice when I hit a wall and couldn’t write another word.

My relationship with Barry does not have a fairytale ending, despite how it began on a sailboat on Peconic Bay back in 1983.

———

Shane O’Neill: I’m Shane O’Neill. I’m here at Eric Marcus’s house and it’s our third session taping of Eric’s oral history. How are you feeling, Eric?

EM: I liked interviewing people better than I like being interviewed.

SO: What—now, forgive me, if this is too personal we can just skip over it… Did anything change in your relationship with Barry? When was your next HIV test? What was your thinking in terms of how it impacted your relationship?

EM: It’s not too personal a question, and I have thought about it. And, um, AIDS pretty much killed the joy in our sex life, and we never found our way back. I was still terrified. Um, and we still practiced very, very safe sex. Um, and I still have anxiety all these years later. And I’ve obviously been tested since—um, I shouldn’t say obviously—I’ve certainly been tested since.

Um, it was such a terrifying time that I couldn’t—even though I knew he was negative and, and I was negative—it wasn’t as if we could throw open the doors and skip into the street and say, “We can do everything! We’re both, we’re both negative.” Barry and I were elated and relieved that we were negative… Um, we didn’t go back to having the kind of sexual relationship that we’d had.

———

Barry and I split up three months after Making History was published and I moved back to New York City. Our relationship unraveled for so many reasons, not just our loss of intimacy. It was complicated. And painful. He threw me out. And he had every right to.

Barry found love again and spent the last 18 years of his life with the love of his life, who was at his side when Barry died of pancreatic cancer in May 2020. He was 67.

I found love again, too. My partner Barney and I have been together for 27 years. My understanding of what it takes to have a mutually satisfying, committed relationship now goes well beyond having a bedroom with wall-to-wall carpeting—100 percent wool. We work at it together. Decades of therapy have helped.

I walk past an otherwise nondescript brick building nestled in a grove of mature London plane trees a few times a week. It’s just a few blocks north of where Barney and I live in Chelsea. I never pass that squat beige clinic without thinking about the first time I got tested there for HIV. Sometimes I get a sinking feeling in my stomach when I think about an all-too-easy-to-imagine alternative reality where the good news I got there was bad. Other times it takes my breath away when I consider how lucky I am when so many others were not. And, still, other times I look at that New York City Department of Health building and think of it as the place where I was born again at age 30.

———

Many thanks to our hard-working crew at Making Gay History, including story editor Sara Burningham, assistant producer and sound designer Rae Kantrowitz, deputy director Inge De Taeye, researcher Brian Ferree, research intern Amelia Donhauser, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. This episode was mixed and mastered by Evan Viola.

Special thanks to Will Coley for his production help. This season was recorded at CDM Sound Studios. Thanks, as well, to our interviewer-slash-oral historian Shane O’Neill and our listening circle, including Syd Baloue, Cheryl Furjanic, Dr. Jamila Humphrie, Barney Karpfinger, Ann Northrop, Benjamin Riskin, Jenna Weiss-Berman, and Mike Winerip.

Thanks also to Solveig Simonsen and Heidi Katz for sharing their memories. And special thanks to research sleuth Tyler Albertario and genealogist Michael Leclerc for helping to find Solveig.

Thank you to the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division for their assistance.

Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers, with additional scoring by Rae Kantrowitz.

This season of the podcast was made possible by the generous support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation; Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS; the Calamus Foundation; the Kipper Family Foundation; Christopher Street Financial; Andra and Irwin Press; Joel Sekuta and Christopher Williams; Bill Kux; Louis Bradbury; Jeff Soref; Kathy Danser; Mitchell Draizin; Bryan, Christine, and Alex White; and scores of other individual supporters.

“Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis” is a production of Making Gay History.

This season was my story. Stay tuned for our next season. We’re planning to bring you a range of voices from the HIV/AIDS epidemic, people you might not have heard from before, but whose stories and experiences will help bring this history to life.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###