Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis — Chapter 4

Episode Notes

“I hope you both die of AIDS,” the young man in the pickup truck yells at Eric and Barry as they wait for the light to change while on a run in Central Park. By 1985, the AIDS crisis has arrived on their doorstep.

———

For a comprehensive overview and useful links related to HIV and AIDS, consult this HIV.gov timeline.

For a New York City-specific timeline, see this New York magazine article. (Please note, however, that the Patient Zero theory referenced at the top has since been discredited; for more information on the subject, watch the documentary Killing Patient Zero.)

This chapter covers mid-1985 to mid-1986. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), by the end of June 1986 there had been 24,976 reported cases of AIDS in the United States and 15,464 deaths. These numbers included thousands of cases and deaths that the CDC had retroactively added to prior years’ totals as more reporting emerged and the disease became better understood. Although a blood test for HIV became available during this time, the actual numbers remain unknown.

March 1985 saw the approval of the first test to detect antibodies of HIV (known until 1986 as HTLV-3 or LAV) in blood. You can see the test kit here. The test was developed to screen blood donations for the presence of HIV, but its sensitivity regularly produced false positives.

The same type of test was soon used for people, but as the episode indicates, its unreliability was not the only reason why so many—including Eric and Barry—were hesitant to get tested; the decision was far more complicated than it might seem. There were no treatments available, and people with HIV/AIDS suffered discrimination and public hostility. If your positive test were known, it could jeopardize your employment, housing, and relationships. You could even have your visa revoked.

In 1985 in New York City, men with an AIDS diagnosis were 66 times more likely to die by suicide than the general population. San Francisco saw a similar trend.

Read the stories of some survivors here.

In the summer of 1985, Hollywood star Rock Hudson released a public statement confirming he had AIDS after rumors of his “mysterious illness” had been circulating on the nightly news. His diagnosis shocked the nation; everyone in the country now knew someone with AIDS. Hudson died just a few months later, bequeathing a quarter million dollars to start the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR). After his death, the national conversation around AIDS grew louder and money for research and services increased dramatically (more about that here)—but so did homophobia and discrimination against those with AIDS.

Some gay men found that their straight friends began to distance themselves. Medical professionals were pressured to steer clear of AIDS patients. Homophobic Congress members like California’s Wiliam E. Dannemeyer stoked the public’s fears that AIDS could be spread through saliva and mosquitos. Around the country, legislation was introduced to try and prohibit people with AIDS from working in healthcare, to mandate that the names and addresses of people with AIDS be turned over to state health authorities, to close bathhouses, and even to bar children with AIDS from attending public schools. The New York Times published an op-ed from William F. Buckley that called for all people with AIDS to be tattooed. (Nevertheless, right-wing radio talk show host Dennis Prager recently chose to deny that people with AIDS were treated as pariahs—a claim that was soundly refuted in this PolitiFact piece.)

In September 1985 in Queens, the borough where Eric grew up, parents organized a boycott in response to the school district’s decision to allow a second grader with AIDS to attend class; 11,000 elementary and junior high school students were kept at home in protest.

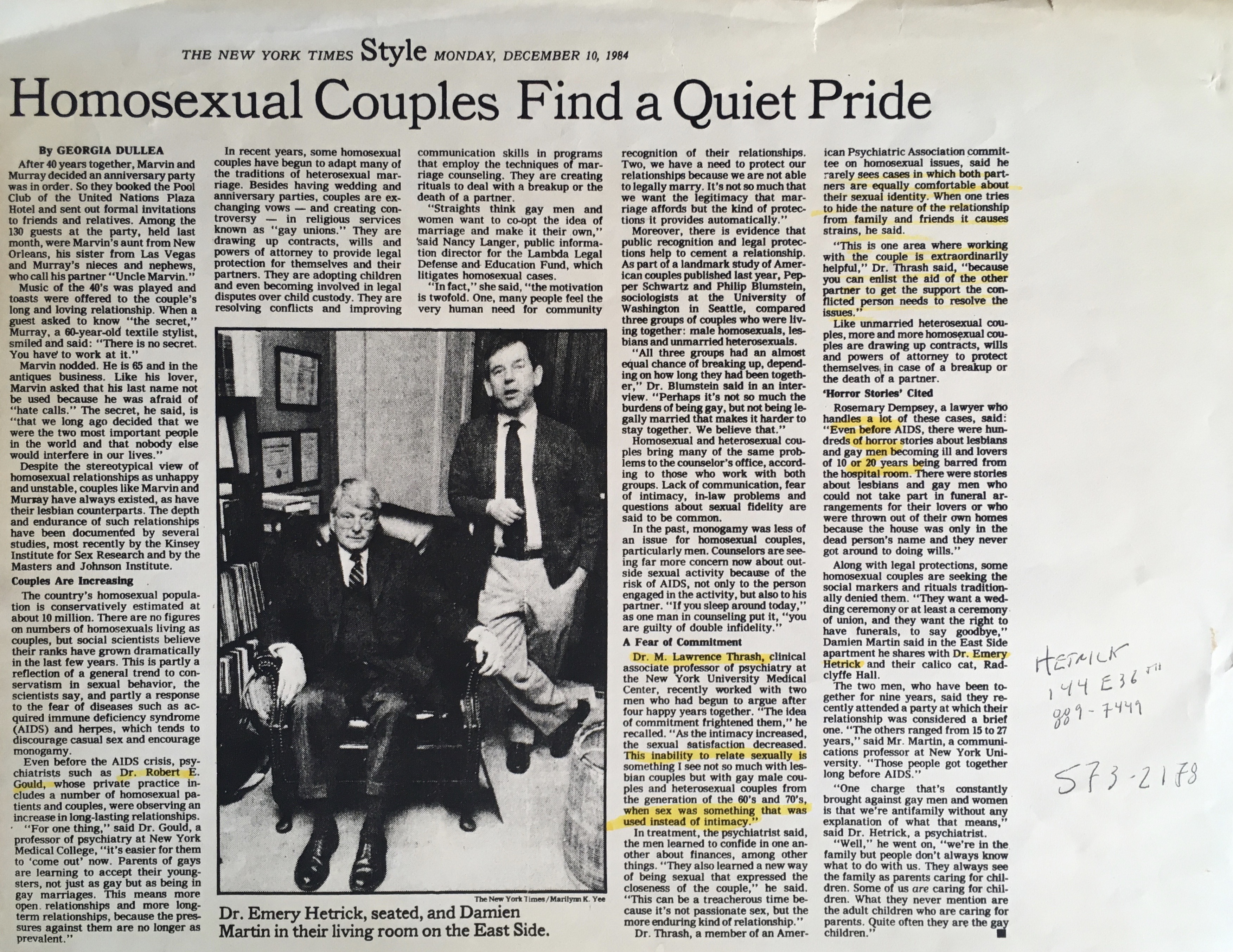

In the episode, you’ll hear the voice of Dr. Emery Hetrick. In 1979, he and his partner, Damien Martin, founded the Institute for the Protection of Lesbian and Gay Youth (IPLGY), later renamed the Hetrick-Martin Institute (HMI). Read more about the organization’s history here, and about the services they provide here.

Dr. Hetrick died from AIDS-related complications on February 4, 1987. Damien Martin died from AIDS-related complications just a few years later. They are buried together in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery; their gravestone reads, “Death ends a life, not a relationship.” Find out more about Hetrick, Martin, and HMI in this Making Gay History episode featuring Damien Martin, and in the accompanying episode notes.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and in this season of Making Gay History, I’m sharing part of my story, of navigating my 20s in the 1980s in New York City. This memoir is also about my friends, the people I met along the way, and what happened to them, as the AIDS epidemic took root and upended our lives.

This is chapter four: “Complications of AIDS.”

It’s the late summer of 1985, and Barry and I are on the tail end of a run in Central Park, a few blocks from our new apartment in an old building on 69th Street and Broadway. We’re waiting at a stoplight and catching our breath. A black pickup truck pulls up alongside us. As the light changes, the driver rolls down his window and yells, “I hope you both die of AIDS.” And then he’s gone. Barry and I look at each other and think the same thing: what gave us away? Couldn’t be our mismatched running gear, which is so not gay. Maybe something about the way we ran?

We’re shocked, but not surprised. AIDS has unleashed waves of anti-gay propaganda and given homophobes just the excuse they need to share their ugliest thoughts.

A couple of weeks later we’re on a plane headed to the Caribbean, our first big trip as a couple, my first trip overseas with a boyfriend, and I’m worrying about how two gay men traveling together will be treated.

Barry loves islands—something about them each being their own little world—so we’ve decided to visit three in 10 days. First stop, Anguilla, where our room comes with a queen bed, and a pullout sofa that’s made up as a bed. When I made the reservation, I didn’t want to tell them we were a couple, and they’ve gone ahead and set up the room for two single guys. We heard that the people in Anguilla are traditionally religious, which usually translates into anti-gay, so in the morning we mess up the sofa bed so it looks like one of us has slept there, and then we do the same for the next two mornings.

When we arrive at our cliffside hotel in Saba, a dormant volcano with a postage stamp-sized airport, we meet Bob and Jim, an older couple from Forest Hills, Queens, who look us over like we’re a couple of lamb chops. They take us under their wings and we have dinner together every night. We’d never met an older gay couple before, and they regaled us with stories about life in 1950s gay New York.

Our final stop is St. Barts, where it’s the mosquitoes that give us the once over and dive in for a meal. St. Barts isn’t yet the international jet set destination it’s become, and our modest one-room cottage in a swampy garden comes without air conditioning or window screens.

On our second afternoon, just back from a swim in the aquamarine water of St. Jean Bay, Barry yells for me from the bathroom. He turns from the mirror and says, “Look!” He sticks out his tongue. We’d always joked about what a big tongue he had, but that’s not what he was asking me to look at. Barry’s tongue is coated with a whitish film, especially in the back.

“Maybe it’s nothing,” I say, but my attempt at reassurance evaporates when I burst into tears. We knew that thrush—a kind of mouth fungus—was an early symptom of AIDS. We’ve both read the alarming studies suggesting that AIDS could have a long incubation period—not just months, but years. And in October 1984, the New York Times had reported new scientific evidence that suggested AIDS might be transmissible through saliva.

Barry and I curl up together on the bed, hold each other, and sob. If you could contract AIDS through saliva, could you get infected from tears?

The day after we get home, I sit nervously flipping through People magazine in the waiting room while Barry is in with the doctor. The doctor asks Barry to stick out his tongue, takes a close look, walks over to the mirror in the examination room, and sticks out his own tongue. He turns to Barry and says, “Yup, that’s what a tongue looks like.” Barry tells me the story on the way home and we wind up standing on a street corner laughing. It wasn’t funny, but you had to laugh. Mostly from relief, but also over our hypervigilance gone wrong.

That study about saliva and AIDS wouldn’t be debunked for another year.

———

Shane O’Neill: So can you tell me about when people in your orbit closer to you began getting sick. Are there some memorable instances of the first people that you knew who started getting sick?

Eric Marcus: My friend Carl got sick first. We were classmates in college. We had been sort of friends with benefits occasionally. Um, he was a brilliant concert pianist, um, really lovely guy, so comfortable in his skin about being gay.

Carl was very sexually active. Um, and so I took comfort in that, thinking, well, you know, even though he went to Vassar, like I did, and we were friends, he’s still different. He was the first to get sick.

———

EM Narration: I had really admired Carl. Someone so comfortable in his sexuality, one of the first people I’d known who didn’t seem tortured by it. He was also cute and we liked each other. Not enough to be boyfriends, but sex with Carl was fun and uncomplicated, the way sex could seem uncomplicated back in the late 1970s.

Carl was a senior when I was a freshman at Vassar—a music major, incredibly talented. He was the kind of friend who lent me his concert dress shoes so I could work as a wedding cater-waiter for extra cash. After he got sick, I visited him often at his studio apartment on the Upper West Side. A grand piano filled the whole room. He slept on a mattress underneath. From visit to visit, I watched Carl melt away, until he was a blind, deaf skeleton. Eventually, he moved home to Pennsylvania to die. Carl died on September 11, 1985. He was 28.

I drive out to Pennsylvania with Carl’s ex-boyfriend Larry, and we meet up with a few Vassar classmates for the funeral. We fill a pew at the church, leaning on each other through the service, often in tears. All these years later I’m left with the marrow-deep memory of the breathtaking shock of Carl’s wasting away, of seeing his skeletal hand come around the edge of his front door to open it the last time we visited and instinctively taking a step back. My first friend to die of AIDS.

Going back into the closet to work for a politician in Queens had turned out not to be a good fit. Shocking, I know. I lasted six weeks. In the fall of 1984, I had quit, stepped back out of the closet, and was lucky enough to walk right back into a job at the computer magazine publishing company. I got a promotion, and a raise, and the chance to ride the subway to work with Barry again. A graphics designer who worked with Barry on PC Magazine became a close friend. Barry and I would double-date with Mark and his partner, and I had seen Mark almost every day for the past year.

———

EM: He was this sweet Midwestern kid who’d come to New York and found success. He was a, a really talented designer. He wore little bow ties to the office and just… We, we, we always, we always said he was cute as a bug’s ear. Started having, uh, light symptoms in the summer of 1985 and then was diagnosed in the fall. That was, that was—such, so many cliches—it’a a wake-up call, it was… Um, and he and his partner were together about as long as Barry and I were together. And they were among—we had hardly any friends as a couple, but they were our friends. Um, and I remember when we sat, sat in their apartment and they told us.

———

EM Narration: Mark and his partner invite us to dinner at their cozy one-bedroom apartment. We know that Mark’s been in the hospital, but they haven’t said why, and we’re hoping it’s not what we fear. “I’m going to beat this,” Mark says, protectively nestled between his partner’s legs—Mark on the floor, his partner on the sofa, hands resting on Mark’s shoulders. I think to myself that that could easily be Barry and me. None of us has much to say over dinner, but Barry and I manage to pledge our support and save our tears for after we’re out on the street.

Mark is back at work the following week wearing one of his signature bow ties and seems great. Barry and I hope that Mark’s natural optimism and his unflagging spirit keep him alive until there’s an effective treatment or even a cure.

Now it’s November of that same year, and David and Louis have come to our apartment for dinner. Those aren’t their real names. David asked me to use a pseudonym because this chapter of his life is very different from the life he lives now. We’re close, but we used to be closer. Our friendship was forged over a memorable night in Denmark all the way back in 1979, when we were both on our junior year abroad from Vassar, and our paths crossed in Copenhagen.

———

David: You were doing a junior year abroad, obviously, there, and I was doing junior year abroad in Stockholm.

EM: Yeah.

D: And we had dinner with my parents…

EM: Yes.

D: … until the restaurant burnt down and we had to leave.

EM: [Laughs.] Yeah. I remember the place started filling with smoke.

D: Yeah.

EM: And, and, uh, we were thinking at first, well, maybe that’s just how it’s done here.

D: [Laughs.] ’Cause they had an open kitchen.

EM: Right.

D: We said, “Oh, they’re just grilling.”

EM: Right. Right. And, and I hadn’t been to any restaurants in Copenhagen because it was so incredibly expensive, but your parents were paying.

D: We never did get a meal, though.

EM: No, we didn’t. What did we do?

D: I think we ate in the hotel.

EM: Oh, oh. Well, that was still very nice. Yeah. Um, but I remember becoming fast friends. We were up the whole—I stayed at your hotel.

D: And we talked all night long.

EM: Yeah, yeah. And that was it.

D: That was it.

EM: Yeah. Um, and we’ve had all kinds of adventures since.

D: Many.

———

EM Narration: I introduced David to his partner, Louis, at our Vassar reunion in June of 1985. Louis was five years older; he was there for his tenth and we were there for our fifth. We were all runners, and I think that’s why I introduced them. Or maybe I was matchmaking. I can’t remember. Either way, David and Louis went for a run together.

———

D: We ended the run, and I think we said, “Oh, well, maybe we should get together sometime.” And, um, that was it until the Gay Pride Run, when we literally ran into each other some weeks later. And we ran the race together, and then at some point we said, “Well, we should get together.” And we continued to date, and then I remember sometime in September, being the romantic that he was, he said, “You know, if we lived together, we could save a lot of money.” [EM laughs.] So he moved in into my apartment in September.

EM: And what did you like about Louis?

D: He had a confidence about himself. He was, uh, very kind, he was thoughtful…

EM: And he was cute.

D: And he was, yes, he was very good-looking.

EM: Doesn’t hurt

D: Does not hurt.

EM: [Laughs.] Um, when I think back to that period of history, I was pretty aware of AIDS at that point, because I, I knew a number of people who’d gotten ill. And I wonder what you were thinking in that regard in 1985, when you wet—met Louis.

D: I was not aware of it. At the time I didn’t know anybody. It’s, it still, back in ’85, felt it was for a certain subpopulation of gay men. And I was very much involved in my career and very much involved with Lou. So in some respects I was probably naive because obviously it hit home soon thereafter.

EM: Um, when did it become clear that there was some kind of—that he wasn’t well?

D: Well, that was pretty amazing when you think about the fact that we literally ran into each other in June, started living together in September, and by October he was having symptoms that he nor I knew what was. And he was having, I think, stomach problems and maybe some other things. So, um, at some point in, I would say, even in November is when he got a full makeup and that’s when he discovered that he was HIV positive.

EM: I remember vividly when, when you and Louis came to our house, our apartment—Barry and I lived on 69th and Broadway—and I can see exactly where Louis was sitting in our kitchen. We had a chair that was from my parents. Um, I don’t remember what he said or what you said.

D: When we told you?

EM: Yeah.

D: I don’t remember… That period of time, and still to this day, has a very surreal quality. It was almost like Alice and, you know, going through the, the glass, and you go into this alternate universe. And I was suddenly put in along with Lou in an alternate universe. But he was and continued to be very stoic and strong. He had a very positive outlook, you know, with his diagnosis and, um, he would not let it get in the way of living his life. And he continued, as you know, to work full-time.

Because, thinking back, November he was HIV positive and still had the symptoms. And then May I was actually at another college friend’s wedding, where I was the, um, um, best man, and I found out literally in the hotel room the night before the wedding that Lou was in the hospital, diagnosed with pneumocystis pneumonia. And I…

EM: I didn’t know that.

D: … and I had to not let it affect me because here was another dear friend getting married, and I was the best man. And I, I can remember clear as day at the cer—at the, uh, reception—obviously the best man makes a speech—and I made a speech about how wonderful it is to see two people who found each other, fell in love, and they’re going to have a wonderful, beautiful life together with many adventures and many wonderful memories. And I’m thinking, in my mind, my lover, my partner, is diagnosed with basically a death sentence where the average lifespan at that time was nine months or less.

EM: Yeah.

D: So, and, and I remember there wasn’t a dry eye in the house at my speech. And everybody came up to me and said what a beautiful, you know, speech I made. And I said, “Well, it came from the heart,” and it did.

So I remember, I went to him to the hospital, and back then—if you remember, Eric, all too well—that’s when hospital staff wore all the garb and the masks and the gloves, and the AIDS patients were put in a separate ward and pretty much under lock and key… So there I was seeing someone who, you know, when I left, you know, less than a week ago, a few days before, you know, he was up and about, and now he’s in a bed with tubes and so forth. And I remember when he came home, the first thing I told him was, “No matter what happens, I will never leave you.” Um…

EM: Why not?

D: Because I made a commitment, and I felt it was important, you know, especially under these circumstances, to keep that commitment. And, uh, in fact, we had a ceremony after that, if you remember. I mean, back then, it wasn’t, you know, a big wedding ceremony, but—may, may have been just been the two of us—but we exchanged rings, you know, and, and then reaffirmed our vows.

EM: When did you get tested?

D: I waited a while because I was fearful that I, if I tested positive, that, um, I wouldn’t be able to take care of him. So I said, well, I don’t have any symptoms of any sort, um, so I waited, I don’t know, maybe a year, maybe longer.

EM: I don’t remember you telling me what your status was, but you must have at some point, because now that we are talking about it, I’m having a, a sense memory of how terrifying it was. Um, because Louis’s diagnosis left me thinking that—what about you? And you were my closest friend, and the thought of losing you… And Barry and I hadn’t been tested yet—we didn’t know. We didn’t get tested until ’88. Um, and given what was going on around us, all of us could have been dead.

D: That’s right.

EM: Yeah.

———

EM Narration: The test for HIV, the virus that caused AIDS, had been available since March 1985, but Barry and I decide not to take it. Remember, there was no treatment, and since there was no treatment, why get a test? The safest thing to do to prevent the spread was just to assume you were HIV positive and behave accordingly. The thinking was that knowing for certain that you were infected, which was a virtual death sentence, would lead to anxiety that could further suppress your immune system. Believing that knowing might make us sicker quicker, we decide to wait and practice super safe sex. We were actually almost too terrified to touch each other.

Barry and I are out to dinner with another young gay couple—we know them from work. We’re at an Italian place on the Upper West Side. Calamari, club soda, couples talk. Evenings like this with other gay couples are part double date, part trying to figure out how to be this thing we’ve never really seen.

We’re asking each other all the questions: who did the dishes, family relationships, finances… And then the conversation turned to the new complications for couples related to AIDS: getting life insurance, preparing a will, coping with the fear of getting sick or infecting each other, drawing up a power of attorney to make decisions for the other if one got sick.

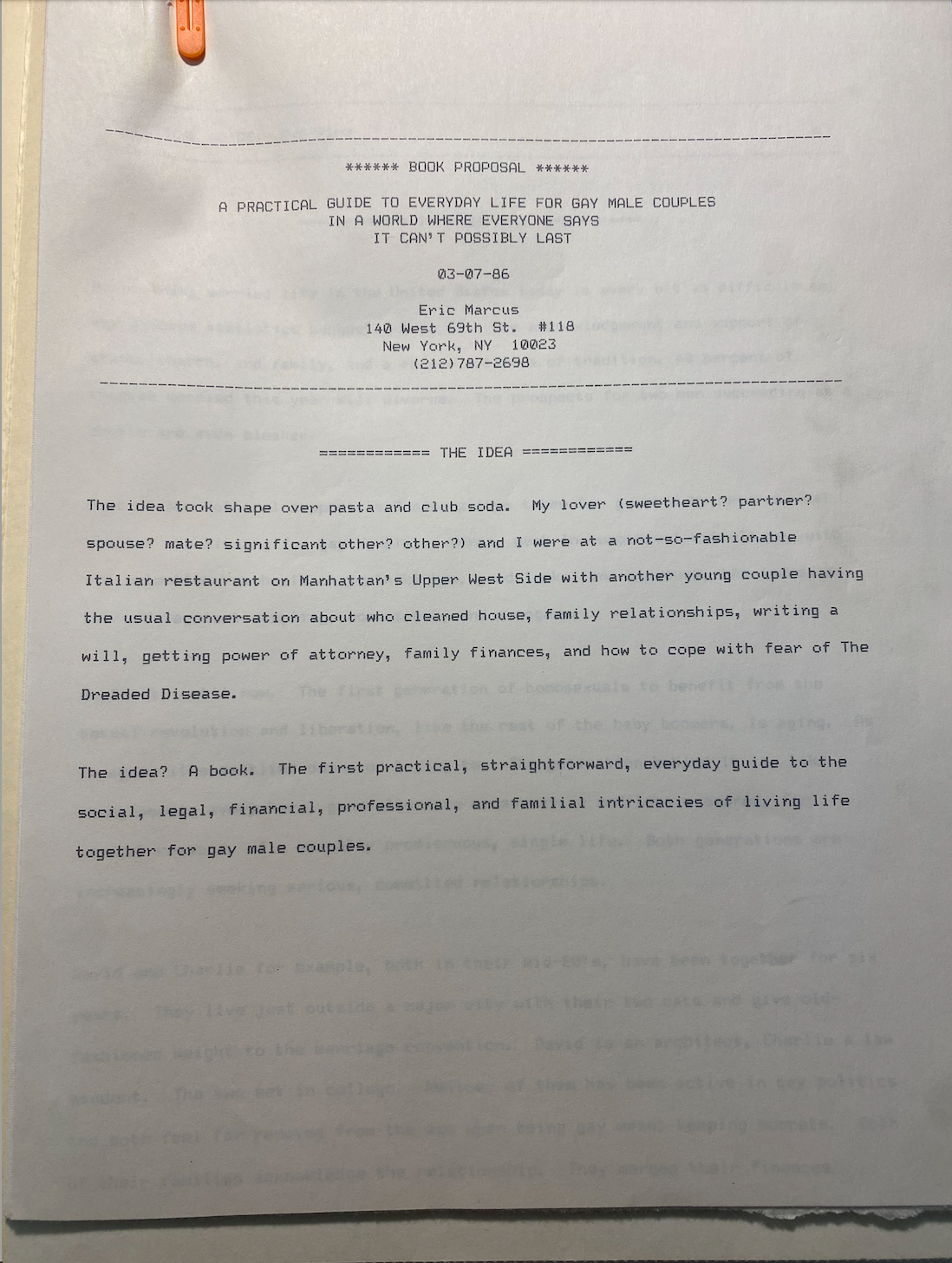

And then I asked a casual question: “I wonder if there’s a book out there that has some answers?” I was sure that there had to be. A couple of days later, I went to the New York Public Library to search the card catalogue for such a book. There wasn’t one.

———

EM: And that was at around the same time I was laid off from Ziff-Davis Publishing because our publication, which was called Computer Industry Daily—it was gonna be the first digital publication for the computer industry at a time when there was no Internet and almost no one had email—uh, we were set to launch, I believe, on September 20, 1985, and we were killed the day before we were to launch. But we were given three months’ severance, so I thought, well, while I look for work, I’ll work on a proposal for a book for male couples.

———

EM Narration: I didn’t want to be a professional homosexual, I wanted to work in mainstream journalism. So through every step of the process of writing the book proposal and trying to sell it to a publisher, I half-hoped that someone would say no and the project would die. The other half of me hoped that I might write something that meant other young gay couples might have some answers—that I might find some answers for myself in a world where almost everyone, including other gay men, said that our relationships couldn’t possibly last.

What I wanted to write was a really practical book about everyday life, from how to arrange your finances to coming out to your parents as a couple. And to get the answers, I’d interview experts and lots of couples. For the proposal, I knew right away who I wanted to interview. I’d clipped their photo from the New York Times the year before. Dr. Emery Hetrick and his partner Damien Martin. Emery in a three-piece suit seated in a wingback chair, Damien in a tie and cardigan standing behind him. The headline read, “Homosexual Couples Find a Quiet Pride.” They couldn’t have looked more conventional, and that was shocking—and thrilling. They were what I aspired to be.

I meet with Dr. Hetrick, who was a psychiatrist, at his compact, book-lined office in Manhattan. I’ve brought along the junky cassette tape recorder I’d used to record interviews when I was working on my senior thesis back in college. Dr. Hetrick is dressed almost exactly as he was dressed in the New York Times article, in a three-piece suit.

The first thing I had to establish was, what did it mean to be a male couple? Did we have to be sexually exclusive? Lots of couples weren’t. What did monogamy mean anyway? So I was eager to hear a professional’s take.

———

Emery Hetrick: These days, if there’s still a range of behaviors, there’s the person who will define being monogamous as being mostly involved with his lover, with his life partner, and not step out maybe more than once or three times a year.

I don’t think that some of the ways we think of as, of, of monogamous is relevant to a relationship. Now if monogamy becomes a, an issue, and people are going to say, “I want you to be monogamous, I don’t want you to sleep with anybody else, I want you to be faithful,” and whatever, they’re setting up a criterion that they probably can’t enforce. And if they can’t enforce it, then, you know, uh, what, what’s that do to the…

I think it’s important, and it has to have a perspective on it that’s one that the couple kind of has a consensus about. And there aren’t any, you know… If you make hard and fast rules, by golly, they’re there to be broken. [Laughs.]

EM: Right. I think the idea is to leave yourself a, um… We have hard and fast rules at home, but we have a, we have an out, um, also. I, because humans are humans, that’s just…

EH: One of the rules that we have, Damien and I have, is that, um, he, he does not want me to tell him.

EM: That’s one of our rules, yeah.

EH: And Damien says, “I won’t tell you either,” but, you know, if we have an affair, then, you know, expect us to be honest and let the other one know.

EM: Right, right.

EH: But if, if he slips off and is at a conference and gets laid, I don’t care. I really don’t, ’cause it depends—I really don’t because our sexual relationship, until I got ill this last year, was so good, I didn’t worry about it.

I understand some people are saying, “If you go out and fuck, don’t come home. If you, if you get AIDS, I don’t want it.”

EM: I can understand that. I mean, it seems very reasonable. Um, that’s like coming home and, you know… “Don’t come home and kill me” is, is, uh, is what that partner is saying then.

EH: That is another thing. See, the, the thing is that you, we don’t know yet what’s going to be the full story here because it takes up to five years…

EM: I’m going to save most of the rest of my questions for when I interview you and Damien. I think that will be more fruitful, um, for us, um…

———

EM Narration: Emery didn’t say he had AIDS, but that’s what I assumed. And even if he’d said nothing about being ill, it was obvious. He looked like he was running a fever and was extremely pale. My plan was to come back for a second interview, so I could interview him with his partner Damien. I’d save my questions about coping with AIDS for then, but first I had to finish the proposal and find a publisher.

I found a publisher in three days.

———

EM: I didn’t know what I was doing because I got off the phone with the editor, and I said to Barry, “I don’t know what I just agreed to.” Um, because he spoke about an advance and I didn’t know what that meant. And he told me how much money it was, but I didn’t know how it worked.

And so I had to call the editor back and ask him for some clarification. But he said to me, “How, how soon do you think you could have it done?” And I said, “Oh, I think I can have this done in seven months.”

———

EM Narration: Before Barry and I paid the check for our celebration dinner at the sushi restaurant around the corner from our place, the excitement about my new book contract fizzled and my anxiety took over. Two things now terrified me. First, I’d never written a book before and I’d just told the editor at the prestigious publisher Harper & Row that I could hand in a manuscript in seven months. And, second, which is more terrifying than the first, what was I going to tell my grandmother and my sister? Neither of them knew I was gay. Next time.

Postscript. I never got to do that interview with Emery Hetrick and Damien Martin. Emery got progressively sicker and died a month after I handed in the manuscript for The Male Couple’s Guide. His New York Times obituary said that he died of “respiratory failure attributed to an AIDS-related condition.” He was 56. Back then, when you were diagnosed with AIDS, your life expectancy was nine months to two years. I would always regret missing the chance to interview them together.

David’s partner, Louis, beat the odds. He didn’t die in nine months or even two years.

———

D: So basically he was diagnosed HIV positive in November. He was diagnosed with AIDS, pneumocystis pneumonia in May. And at that time he got nine months. He lived another seven years. So he lived—we lived—with him being sick for seven and a half years, out of less than an eight-year relationship. So that’s pretty much all I knew.

EM: Yeah. I remember. Um…

D: All too well. You were an amazing pillar for me because, uh, again, not many people knew many of the layers of my life except for you and a few other people. And I don’t think I ever shared with you how much that meant to me, because I did not have an outlet. And, you know, you were the kind of person that was never judgmental, always supportive, always there. And, uh, that got me through some very difficult periods.

EM: Well, you’ve always meant the world to me, so, um… What was it like living with somebody who had AIDS?

D: Well, again, he was not someone who, you know, lived as an AIDS patient, although at, at some point soon thereafter, he got a job, as you know, at GMHC. And he was also one of the first people to go to where there were experimental drugs. I remember he and I went to France because there was a physician that had some kind of a treatment, and I remember that he was also one of the first people to do AZT. And at the time, AZT was prescribed—you had to take it every four hours. So I would be the one that would set the alarm. I would wake him up. I would make sure he took his medication when I was home with him. So we didn’t even sleep through the night—you know, it’s like having a, a newborn—for months and months.

There was also the honeymoon period, where things kind of just stabilized for him. And so he, you know, continued to live a full life. We traveled, he worked full-time. It wasn’t always living under the, um, roof of sickness, but it was always present, obviously.

EM: What did you think about him going to work for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis?

D: It felt that this is what he needed to do. He was really diligent in what it would take to stay alive. He wanted to live, he had a strong will up until, literally, the, you know, the day he died. And so it felt it was the right thing for him. For me, it was like, I was very private and had my own questions of my identity, and there I was basically with a very public figure, because he became the poster boy. His disease became just a lot of who we were as a couple.

EM: How did you navigate that? Because I, I remember—you’ve always led a life with lots of layers to it. How did you navigate that?

D: I think in hindsight or looking back, I leaned on his strength also. I think we became a source of each other’s strength and, um, and we did the best we could to live a normal life. Because he didn’t ever talk about what he may have been going through physically, mentally, emotionally…

EM: If I remember correctly, he never spoke of the possibility of dying.

D: No. No, he did not. I think I remember there was a dinner that you were at, and he had really basically pretty much stopped eating. He just could not eat food. And he was, again, incredibly weak and rail thin. Um, but he insisted on going out. He would, you know, cut a piece of food and put it on his fork, and then he would hold the fork up, but he wouldn’t eat it, knowing that he really couldn’t digest it. And I said, “If you don’t put that,” excuse my language, “effin’ piece of food in your mouth, I’m gonna take that fork and I’m gonna stab you with it.” And, um, but that was pretty much near the end.

EM: Yeah. I was at that dinner.

D: You were at that dinner.

EM: And I remember you threatening Louis because he fell asleep mid—with the fork in the air.

D: That’s right.

EM: We were at a restaurant on 72nd Street, and—I think it was 72nd Street—and he had ordered a lot of food, and he did that… He, he was so determined to live normally, he ordered food as if he could eat.

D: He, he just really was—I never want to say denial ’cause he knew exactly what he needed to do to stay alive—but it was not something he wanted to talk about.

EM: Yeah. Yeah. But when, when you threatened him, when he—to stab him with the fork, um, he did not smile. Um…

D: No.

EM: No.

D: But he, he might’ve eaten a piece of food. And it’s funny, you know, you talk about him not being very romantic. He, he was not, and he was not, um, flowery in his language, although, you know, I knew we loved each other. But there was one moment that always, you know, kind of stuck in my mind and my heart was, maybe a few days before he died, and I was in the kitchen and I fainted. Just passed out on the floor, not for long.

And, you know, I opened my eyes and there was Lou—you know, this poor, gaunt man, my, you know, my lover, my partner—and he looked at me because he could not help me up, he was so weak. He said, “I am so sorry for everything that you have had to go through, but I could not have done it without you.”

EM: And I, I’m not sure I can imagine what it took for him to say that, because that was not in his nature. And it meant acknowledging that, acknowledging what a huge lift it was to care for him in those years for you.

D: He did not—you know, he would not go into hospice, he wouldn’t go into a hospital. He was determined, he—even when GMHC said, “Lou, you know, don’t come to work anymore,” he would still go into the office, and they would call me and say, “We don’t know what to do,” because he would not not come, but we, we basically put him on disability because he really wasn’t able to, to function. And I said, “Well, you know, put him someplace and then you can always send him home.”

And then finally I got hospice for him—basically 24-hour care. We only had maybe three days, I don’t remember, that we had hospice. And I remember he was, you know, um, very uncomfortable, very, um, agitated, and I said, “Louis, let’s just, let’s lay down on the bed, let’s rest,” you know? Um, and, you know, he, he settled down, and I didn’t know what it was called at the time, but it was the death rattle that you could hear in his throat. And I put my arm around him and I might’ve been maybe asleep for 15 minutes. And then, I think that was a gift from God, because when I woke up, he had died. And I looked at the window and there was a bird, a pretty little bird, and I said to myself at that time, that’s Lou and he’s leaving me, but he’s gonna be in a good place.

And, um, you know, I stayed with him for a little bit. It wasn’t even until when I woke up in bed and, you know, he had died, when I saw him truly as an AIDS patient. He, ’cause he—because, again, my belief was that his soul had left, had become or gone to this bird, the bird had left. So what was just left was just the shell of, you know, his body, and it wasn’t even Lou anymore. And it’s that, and it really—that’s when I saw him as someone who really lived with, got sick from, and died from AIDS and, and the impact it has, you know, on a, on a human being.

But going forward a little bit, a memory that I have with you—that you and I still laugh about, even under the darkest of circumstances—was, I turned to you to help me write his obituary. And there—’cause you were such, and still are, such a great writer—and I remember sitting side by side in your apartment, you know, and, oh, and, you know, yes, it’s a very, very sad moment, but we were laughing at some of the memories and some of the things we couldn’t put down in the obituary [laughs], and when we finished, we turned to each other, as I remember it, and we both said, “That’s good copy.”

EM: [Laughs.] We did. We did. We somehow managed—yes. Yes.

D: “That’s good copy.”

EM: Yeah. And I remember feeling that it was so important for me to hold it together during that time for you, that you, that it was, you were going through enough, but at the funeral… It was, you gave your, your eulogy, um, and it was at, at Riverside…

D: Yes, it was.

EM: And it was a packed house.

D: It was a packed house.

EM: Hundreds of people. Um, I remember you finished, you sat down. I was right behind you. I burst into tears. And I don’t know if you said to me then, or later, like, “Oh, come on,” you know, “couldn’t you have held it together a little longer?” And, and I couldn’t.

D: But I do remember that what was important to me is that he had the ring on, that, um, I had the matching one, too. And that was, that was a connection. And it’s interesting because, again, I never considered myself a religious person, but I always, after that, I knew that he was my angel and still is. That he, that—’cause, as you know, my life went in a much different direction than it could have—and it was just like this comfort, that his way of saying “thank you for everything” was to become my angel.

You fucker.

EM: [Laughs tearfully.] Sorry. Do you ever think about, uh… [EM and D laugh.] Thanks, David. Um, hmm…

———

EM Narration: We couldn’t pull ourselves together after that—two men with a lot of history and 45 years of friendship dissolving into tears, then laughter. We hadn’t talked about that time since that time, and it was tough. I’m grateful David agreed to talk. AIDS changed everything forever, for all of us.

———

Many thanks to our hard-working crew at Making Gay History, including story editor Sara Burningham, assistant producer and sound designer Rae Kantrowitz, deputy director Inge De Taeye, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. This season was recorded at CDM Sound Studios. Special thanks to interviewer-slash-oral historian Shane O’Neill and our listening circle, including Syd Baloue, Cheryl Furjanic, Dr. Jamila Humphrie, Ann Northrop, Benjamin Riskin, Jenna Weiss-Berman, and Mike Winerip.

A very special thank-you to David for trusting me enough to go back in time to share his memories.

Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers, with additional scoring by Rae Kantrowitz.

This season of the podcast was made possible by the generous support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Calamus Foundation, the Kipper Family Foundation, Andra and Irwin Press, Bill Kux, Louis Bradbury, Jeff Soref, Amy Quispe, and scores of other individual supporters.

“Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis” is a production of Making Gay History.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###