Greg Brock

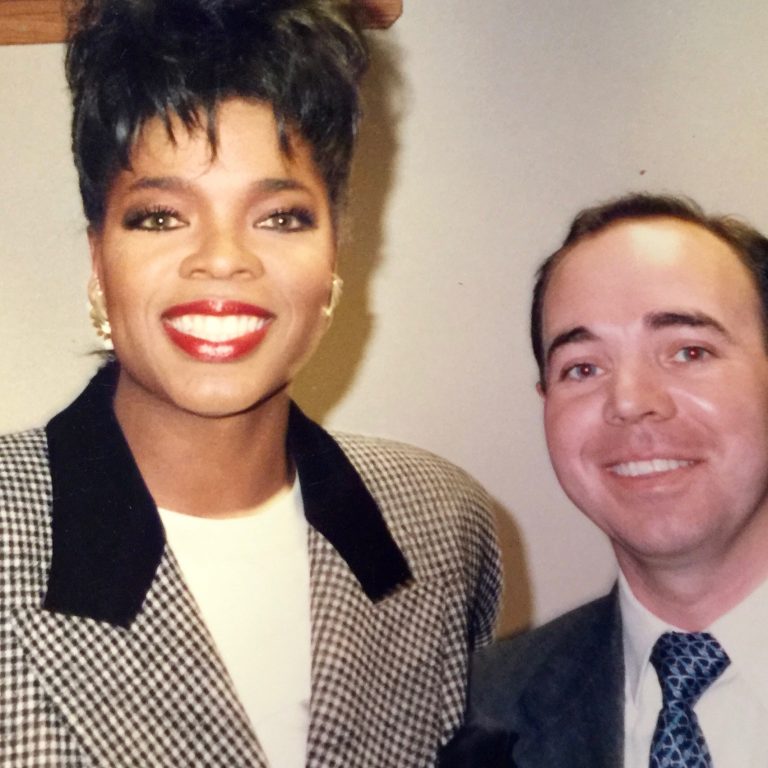

Oprah Winfrey and Greg Brock, Chicago, Illinois, October 11, 1988. Credit: Courtesy of Greg Brock.

Oprah Winfrey and Greg Brock, Chicago, Illinois, October 11, 1988. Credit: Courtesy of Greg Brock.Episode Notes

Greg Brock blazed a trail for LGBTQ jounalists by being himself. No small thing given what the world was like for journalists when Greg was building a career at big city newspapers. At the time of his 1989 Making Gay History interview, Greg had been out on the job at the Charlotte Observer, the Washington Post, and the San Francisco Examiner, where he was the assistant managing editor in charge of page one. Greg was the highest level openly gay person working at a mainstream newspaper anywhere in the United States.

If you’re thinking that it was no big deal to be an out gay man at the San Francisco Examiner in the late 1980s, read Greg’s interview in the original edition of Making Gay History, and you’ll see that what Greg did was an act of courage—and a gamble. It could have cost him his career.

For those of us who can remember the first National Coming Out Day when Oprah Winfrey featured a panel of guests on her syndicated television talk show that included Greg Brock, Greg left an indelible impression. But it wasn’t until I was interviewing Greg at his office at the San Francisco Examiner that I realized I’d seen Greg on the show and that he was the self-described “sissy from Mississippi” who had won my heart and the hearts of millions of Oprah’s viewers.

Greg Brock spent the final two decades of his career at the New York Times and retired on December 1, 2017. He divides his time between Oxford, Mississippi, and New York City. To learn more about Greg, National Coming Out Day, and the history of openly gay journalists, have a look at the information, links, photos, and episode transcript that follow below.

———

In 2012, Greg was awarded the “Silver Em” by the University of Mississippi. The Ole Miss University of Mississippi News article announcing the award provides a great overview of Greg’s career as a journalist.

Read Greg Brock’s oral history in Making Gay History, which includes his account of two gay bashings that contributed to his determination to live his life out of the closet.

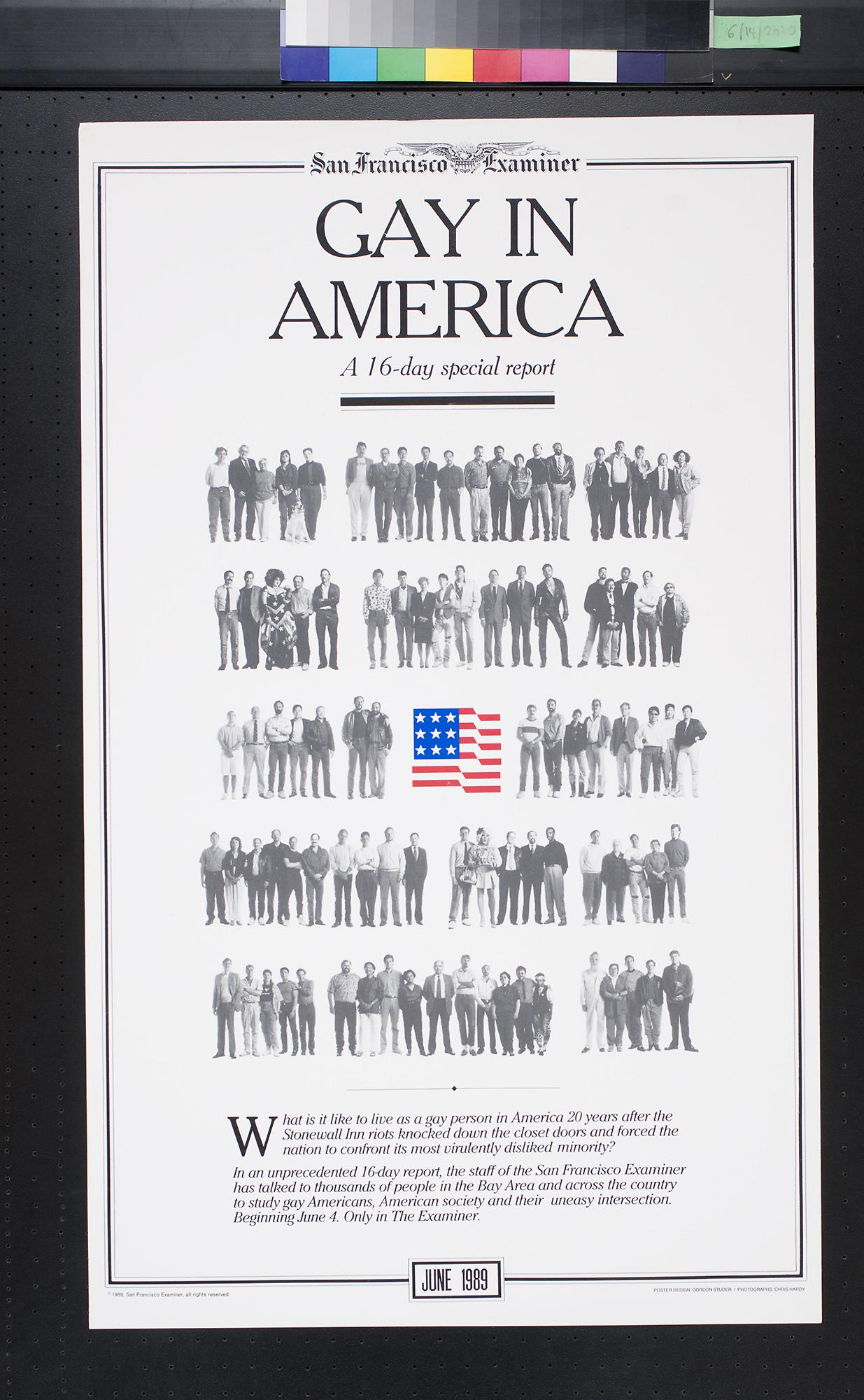

The June 1989 “Gay In America” 16-day San Francisco Examiner newspaper series that Greg Brock championed along with editor Carol Ness can be found in the collection of the Oakland Museum of California. You can see a closeup of the series’ front page here.

To hear about the experiences of journalists who came out on the job when most journalists working in mainstream media were still closeted, have a listen to our episode featuring the late CNN anchor Tom Cassidy. We also recommend a terrific audio documentary about the late New York Times journalist Jeffrey Schmalz called “Dying Words: The AIDS Reporting of Jeff Schmalz and How It Transformed the New York Times.”

Read this December 1992 article in the American Journalism Review for a great overview about what it was like to be an openly gay journalist at that time.

National Coming Out Day was launched on October 11, 1988. It was co-founded by Jean O’Leary and Robert Eichberg to mark the anniversary of the 1987 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Learn a bit more about National Coming Out Day’s history here. And have a listen to Making Gay History’s two episodes featuring Jean O’Leary here and here. At the time Jean co-founded National Coming Out Day, she was executive director of the National Gay Rights Advocates (NGRA). The ONE Archives at the USC Libraries houses the NGRA collection.

To watch a 15-minute clip of the National Coming Out Day episode of the Oprah Winfrey Show on which Greg was a guest, click here. Greg appears at the very end of the clip.

The Association of LGBTQ Journalists (NLGJA) was founded in 1990. You can read the the history of the organization here. In the late 1980s, Greg Brock and other San Francisco Bay Area gay journalists hosted gatherings that ultimately led to the founding of NLGJA. What follows is Greg’s recollection of those gatherings, conveyed in a December 11, 2017 email in response to a question from Eric Marcus regarding whether Greg was ever involved with NLGJA:

No. Believe it or not, I was never a member. Funny story about what led to that. When I went to San Francisco I knew no one. So a guy got a group of gay journalists together. Randy Shilts was there. Maybe 30 of us. Had it at my place. About every six-eight weeks we would have another. I hosted several. Other folks hosted it, too.

The last one we had was at David Perry’s; he made it kind of a going-away thing for me. Leroy Aarons [the executive editor of the Oakland Tribune and founder of NLGJA] came for the first time. He was not out at the time. He was blown away by the number of people.

So he got four or so of us together before I left town to talk about formalizing it. I went back to D.C. and the rest is history. [Roy] came out at ASNE [American Society of Newspaper Editors], formed the group. But I never got involved.

———

Episode Transcript

I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History!

Greg Brock never liked the limelight, but the self-described “sissy boy” from Mississippi, didn’t get a choice. From the moment he was born in 1953, it was clear he was different. And the way he was different brought him the kind of attention no one wants—from bullies, gay bashers, and a disappointed father.

But that didn’t keep Greg from excelling in a profession where just being himself made him a role model and trailblazer at some of the most important newspapers of the time—the Charlotte Observer, the Washington Post, and by 1987, at the San Francisco Examiner, where he was the assistant managing editor in charge of page one.

In the world of journalism back then, an out gay person at that level of the business was a really big deal. Greg was also a driving force behind a 16-day series in the San Francisco Examiner called “Gay In America.” It was published for the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising. No one had done anything like it at any news outlet before.

When I met Greg in 1989, it was rare to find anyone working in mainstream journalism who was gay and out. The reason was simple. For most people in most places it was a career killer. I learned that lesson myself as a young producer at CBS News. In 1988 I was told by a senior executive that they’d never put an openly gay newsperson in front of the camera. I left CBS soon after to write my book Making Gay History.

So here’s the scene. I’ve traveled from my apartment on Russian Hill in San Francisco to Greg’s office downtown on Mission Street. It’s just a couple of months since the publication of “Gay in America” and Greg is getting ready to leave the Examiner to go back to the Washington Post. He’s a little guy with bright blue eyes, a round face, and sweet smile. He’s a few days shy of his 36th birthday. Except for his tie, Greg and I are dressed almost identically in journalist drag—pressed shirts and khakis.

We’re a long way from where Greg grew up—the tiny town of Crystal Springs, Mississippi in the segregated South. As I clip the microphone to his shirt and press record, he takes me back to where he was born.

———

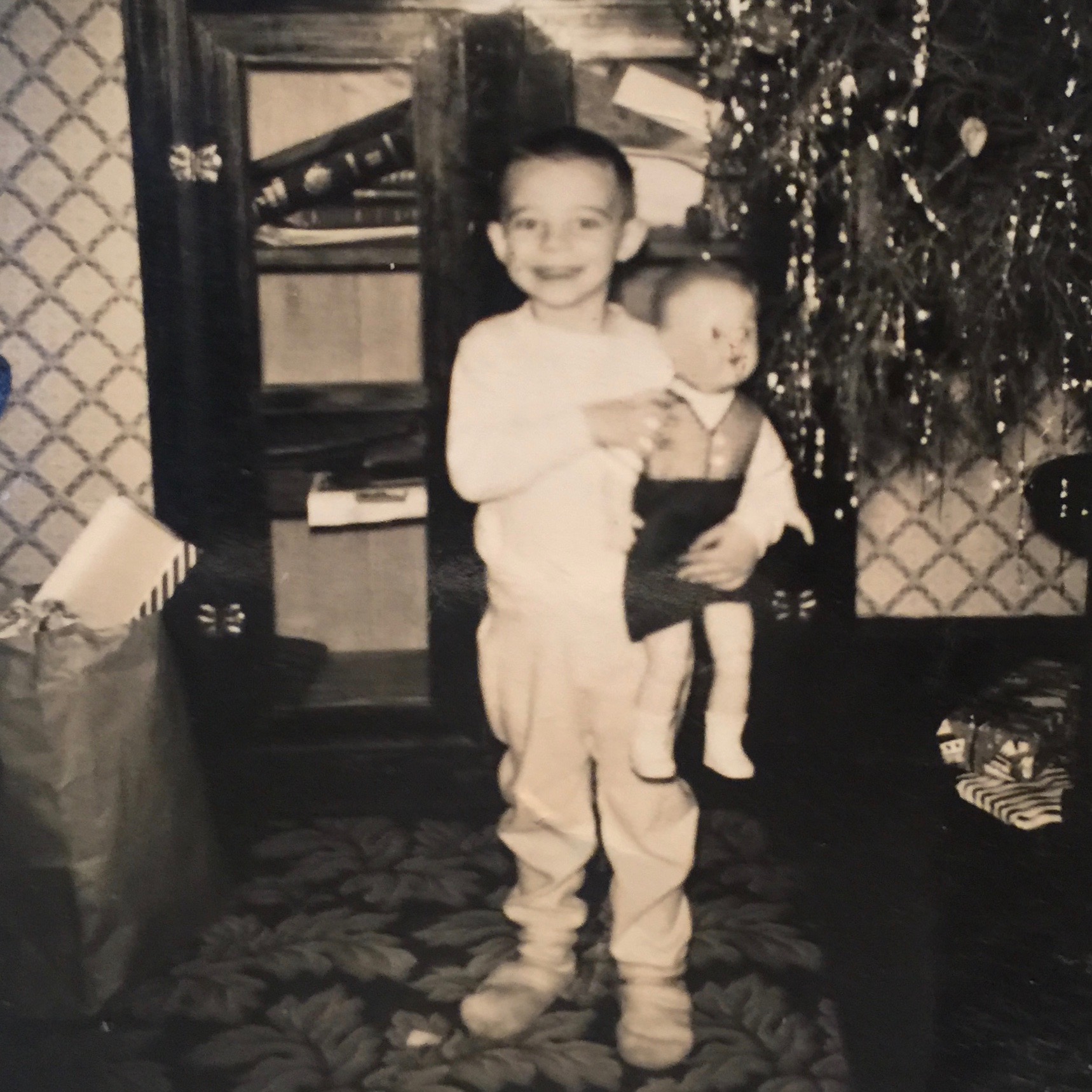

Greg: I mean, I was a sissy boy from the word go. I played with dolls. I took baton lessons. I was a mama’s boy. Effeminate. I was a pretty, pretty little boy. As a child I was really… huge blue eyes and was very soft and very pretty. In fact, my birth certificate, I was marked as a girl. And that was always the running joke at family reunions. My dad, that’s the only thing he ever said, “Well it took him years to figure out otherwise.”

I’d go home and cry myself to sleep a lot of nights. Huge white antebellum home, columns all the way around it. Um, in that town, the context of that town, probably upper middle class. We had money that a lot of people didn’t, though we didn’t have the old family name, which is really what counts there. Um, mother, father, three children. Nice car. You know, you get the scene. Uh, we went to church every week. And we did everything you’re supposed to do, except under that roof there was nothing. There was no love. There was no interaction. There was no nothing.

You know, my dad wanted me to play football and do all these things. Um, he was a very masculine, very blue-collar type. And, uh, you know, I didn’t do anything the other boys my age did. I didn’t like to hunt. I didn’t like to fish. My dad took me to deer camp once. Deer camp being this place that he and all of his buddies had, they belonged to. It’s kind of an old house and about 30 men go and they have bunks. And they have two Black women who cook ’em meals. And they go out in the woods and kill deer. So I went. I don’t remember how old I was—10, 11. I didn’t have a gun or anything, got me a gun. You know, I was like… I wasn’t gonna kill a deer. You know, god, it was just awful, just disastrous.

Eric: You must have felt like you were dropped on the planet from somewhere in outer space.

Greg: Yeah. Every year you got further and further away from your family. One time I went home and—they always put it in the paper, you know, the weekly paper, about who visited whom and who’s home and all this kind of stuff. And I was in the personals column. My mother had put in there that “Greg Brock, editor of the Washington Post, has been home to visit.” I sort of tell Ben Bradlee he had been, you know, booted out. But again, not quite ever getting it.

Eric: What is the name of your town again?

Greg: Crystal Springs.

Eric: Crystal Springs, Mississippi.

Greg: And, uh…

Eric: How many people?

Greg: 4,500, roughly. About 20 miles south of Jackson, Mississippi.

But, uh, since we’re on this, I might as well tell you, I came out last year on the Oprah Winfrey Show to them.

Eric: Were you one of the…? You were the one!

Greg: I was the one from Mississippi, yeah.

Eric: This is Coming Out Day 1988.

Greg: Right. October 11th.

Eric: The National Gay Rights Advocates planned this.

Greg: They called me up and I said, “Why would I do that? Everybody in the world knows I’m gay if they want to know it. I’m very open about it.” “And so what about your family?” I said, “Gulp.”

So all they were doing is submitting my name, though. But I knew it was a given that I was going to make it because my dad and Oprah Winfrey are from the same home town in Mississippi. Kosciusko, Mississippi. The producer interviewed me and talked to me and said, “Well, we’d like you to fly up tonight and do the show in the morning. But the deal is you call your parents and tell them and would you ask them if they would consent to a telephone hookup.”

Eric: Oh, my… This is a little dramatic.

Greg: Oh, yeah. So I call my dad. It was Monday afternoon, October 10th. I’ve never felt so alone. Just, my knees started shaking. There’s just no way to describe it. I was scared. I was… I just didn’t know and…

Eric: You’re a grown man by now.

Greg: I was a grown man. I was 35 years old. And, you know, you call your dad, you know and… It’s a Monday afternoon. He’s semi-retired and he has his little business kind of next to his house now and he gardens a lot. Oh, I just had this mental image of what he was doing. I could see his little house. They live out in the country. Um, Mississippi some things don’t change. You go out and check the mailbox every day. You get a letter from long distance, you know, across the miles, it’s really a big deal. Or when a long distance phone call comes. I’ve been out there and I know what it’s like when you get the phone call that someone’s died or this has happened or that’s happened. And that’s about what I was about to do to him. I was about to, on a Monday afternoon, October 10th…

Eric: 1988.

Greg: 1988, shatter his life.

Eric: Your father picks up the phone…

Greg: My stepmother picks up the phone. “Ah, well, we’re out in the garden…” You know, the whole bit.

Eric: Did you dial more than once?

Greg: No, just once. So I asked to speak to Daddy and I said, you know, keep… She said, “Let me get him.” And I said, “Well, you stay on the phone, too.” So immediately my voice…I said, “Well, there’s something I wanted to tell y’all and been wanting to do this for a long time and just never it’s been appropriate.” And, so my voice started cracking, breaking.

And she said, “Well, honey, that’s alright, what is it?” I said, “Well, I guess the best way to say it is the good news I’m going to be on the Oprah Winfrey Show tomorrow.” And she says, “Oh, that’s wonderful, that’s wonderful. I’ll have to watch it.” And I said, “Well, the bad news is I’m not sure you’re going to want to invite the neighbors over.” So that kind of broke the ice a little bit and I chuckled and kind of got my voice back.

I said, “That’s the news, but it’s the type show she’s doing.” I said, “Since I’ve been out in San Francisco,” I said, “I’ve sort of moved into the public eye a little bit. There have been some feature stories written about me, or a feature story.” And, I said, “A lot of people know me here now.” And, I said, “There’s a reason for that. But,” I said, “I can’t mail you these articles, clip ‘em out.” I said, “I’d like to, I’d like to share it with you. And I’d like to think that you, you know, this would be in the same vein as when as when I was at Ole Miss and I got awards and I was this and, you know, you always got the newspaper clippings and you put ‘em in the scrapbook. But,” I said, you know, “I guess my fear is that you wouldn’t put these clippings in your scrapbook.” And, I said, “The reason is,” I said, “in this city I’m very well known because,” I said, “for years now at newspapers I’ve worked at,” I said, “I am gay and I am very open about, but I’ve never told y’all.”

And I was just waiting–I can’t remember the precise conversation, the reactions, but I remember my dad saying, well, that he had prayed a lot that his suspicions were wrong. And then we went on to talk and, you know, it was kind of teary. But he really opened up and he talked a great deal. And I was surprised. And he even said that if they called him he would talk to them on the telephone, which stunned me. They didn’t. They ended up choosing my mother.

Eric: What kind of reaction had you expected from him?

Greg: Hang up. Tell me not to ever come home again. Didn’t want to hear from me, or whatever. Um, but they said, you know, that they loved me and wanted me to come home to visit and stuff like that.

That made it easier calling my mother, but I couldn’t reach her. So I was already in Chicago at the hotel before I finally got a hold of her. And that was again just the opposite of what I expected. I told her. And she didn’t say much. I thought she would start crying and falling on the floor and, you know, whatever.

Um, she was pretty low key about it and went into the typical Mississippi thing about, which I had heard for years, “Well, you know I’ve got Black friends, too.” Well, she said, “Well, I know son, there are these two lesbians that come in the store all the time and they’re just as nice as they can be.” And, um, a short conversation—she didn’t say much. And said she’d talk to the Oprah people if they called her.

So, the limo picks me up and I go down there…

Eric: Were you nervous at all?

Greg: Oh, uh, not really.

Eric: Because you’ve done the worst part.

Greg: The worst part was over.

It’s an all gay audience, been hand picked by gay rights people there, or parents of gays, the PFLAG people were there. So it was a friendly audience. And, um, the format was the first five minutes Oprah says, “It’s National Coming Out Day. People’s lives today will be changed. They’re about to tell people…”

So they start popping up in the audience at mics saying, “Hi, Mom, hi, Dad, there’s something I’ve been wanting to tell you. I’m gay.” “Hi cousin Sid, you know, you’ve made me feel really uncomfortable at all these family reunions and I just wanted you to know I’m gay.” It was great. And, uh, then she took us one by one and did our individual stories.

So she started talking to me and the whole bit and really, she really got into the southern routine, you know, it was great. And, uh, that made me that much more comfortable. And then, you know, just she’s reading cue cards and she says, “Well, we have Greg’s mother, Mrs. Sharpe, on the phone.” She’s remarried, was remarried. That’s the second part of the Oprah story.

And, um, my mother’s very southern, very country sort of soft spoken. And, um, she said, “Mrs. Sharpe, are you there?” And she said, “Yes I am.” I should have thought, what are they going to do with the camera. This is a voice being piped into the studio. It’s either on me or Oprah, right?

Eric: You didn’t think about that.

Greg: And she starts talking and she says, “Well, Mrs. Sharpe, what have you been thinking since Greg called you last night.” “Well,” she said, “I haven’t gotten a wink o’ sleep all night.” And I thought, oh my god! What have I gotten myself into? I could hear how distraught she was in her voice. She sounded pretty cool about it the night before. Well…

Eric: She was in shock.

Greg: She had been in shock. She had called my little sister and my redneck plumber brother-in-law and I was sure that, like, they had been up all night and the family was just in a tizzy. I mean, they live for these things in the South, you know. Crises is what gets a southern family from one day to the next. And so Oprah says, “Well, like, what did Greg say when he called you? Did he ask you about your gardening or how the weather was or did he just lay it on you say, ‘Well I’m gay.’” And she said, “Well, he just laid it on me.”

So they talked back and forth. And she did tell Oprah she had never suspected. And I, just like, I made this horrendous face. It made my dad really mad that she said that. And, um…

Eric: Because she had in fact suspected. You talked about it.

Greg: Of course. Hell, she had gotten me to take baton lessons at age five. And, uh, so, then she talked about her dad and how he had married late in life and she thought with my career and everything that I would eventually get around to finding the right person and settling down. And Oprah said, “You mean, the right woman.” She said, “Yes, the right woman.” But she ends by saying, you know, she says, “But the bottom line is that he’s my flesh and blood and my only son and I love him.” And the audience just burst out into applause. It was really very nice. And then she talked to me some more, Oprah did. And, uh, it was quite an experience.

But then four days later… So I come back to San Francisco—that’s Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and she calls me. She said, “Well, your sister said you were gonna call me this weekend, wait a few days. But,” she said, “I wanted to call and tell you that it’s been a rough week, son, and I haven’t been anywhere in a long time so John”—that was my stepfather—“is gonna take me down to New Orleans just to get away.” I said, “Well that’s good, y’all should go. Enjoy yourselves. Get some rest. I’ll talk to you when you get back.”

Saturday morning, the… my machine has a message, hysterical message from my little sister that my step father has dropped dead of a heart attack in New Orleans. I immediately pick up the phone and call my ex-lover who I talk to every day, still. And I says, “My stepfather just dropped dead with a heart attack and I know it’s gonna be my fault.” So sure enough, there was that discussion in the family. “Well he just broke his mama’s heart.” No matter that my stepfather had one lung, one kidney, and had had four heart attacks. You know, “Just watching Greg’s mama just with a broken heart and he just couldn’t stand the strain, just keeled over with a heart attack.”

And then his mother, by the time they got his body back to Mississippi, his mother had died. So they had a double funeral. And I say in the South there’s nothing better than a double funeral—than a double wedding, than a double funeral. I mean, they love those, you know. They had matching casket pieces and buried ’em side by side. So I have a great book in me, too, when they all die off.

So I didn’t go back. No, um, umm. No way. I decided my absence would be best. I had caused enough stir that week. ‘Cause I’d love to have known what that little town was saying. They were in quite a stir. You know, all the old ladies were calling each other. “Well, I always knew it,” they said, “I just always knew he was queer.”

Eric: This must have changed your life in some way.

Greg: Yeah, it started my life, I think, on a lot of levels. Living a lie. Not being yourself. Not being open. Carrying this tremendous burden around. Ooh. It’s a burden lifted.

Eric: And now it’s theirs.

Greg: Yes, now it’s theirs.

———

Greg Brock did exactly the opposite of what his tormentors expected he’d do. Instead of cowering, Greg chose to be himself. And it wasn’t just the teasing that gave him the determination and courage to live his life openly. Greg was the target of gay bashers when he was living in Charlotte, North Carolina. Twice.

In preparing for this episode, I re-read Greg’s story in my oral history book and found myself in tears revisiting how Greg was beaten the first time and then kidnapped from his own home the second. Greg thought he’d be killed, but found an opening and ran for his life—and that experience left him all the more determined never to hide. His bravery throughout his life takes my breath away.

Just recently, Greg retired from his job as a senior editor at the New York Times. He’d been there for two decades. I was in touch with him the other day and he told me that he’ll be spending the next year in Oxford, Mississippi, where he has a small house not far from Ole Miss, the university where he got his undergraduate degree in journalism back in 1975. That’s the same university that gave Greg the Silver Em in 2012. It’s an annual award given to a Mississippi-connected journalist whose career has “exhibited the highest tenets of honorable, public service journalism, inside or outside the state.”

Making Gay History is a team effort. Thank you to executive producer Sara Burningham and audio engineer Anne Pope. We had production assistance from Josh Gwynn. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers. Thank you, also, to social media strategist Will Coley, our webmaster Jonathan Dozier-Ezell, researchers Bronwen Pardes and Zachary Seltzer, and photo editor Michael Green. A very special thank-you to our guardian angel Jenna Weiss-Berman.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season three of this podcast is made possible with funding from the Ford Foundation, which is on the front lines of social change worldwide.

If you like what you’ve heard, go ahead and write a review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. Your reviews really help other folks find us.

And if you haven’t subscribed yet, go to makinggayhistory.com for a full list of options. That’s where you’ll find all our episodes, including photographs, notes, and links to additional information about the many people we’ve featured in Making Gay History. And don’t miss the totally adorable Christmas 1956 photo of Greg Brock clutching his most prized present in front of the tree: a baby doll.

So long! Until next time!

###