Tom Cassidy

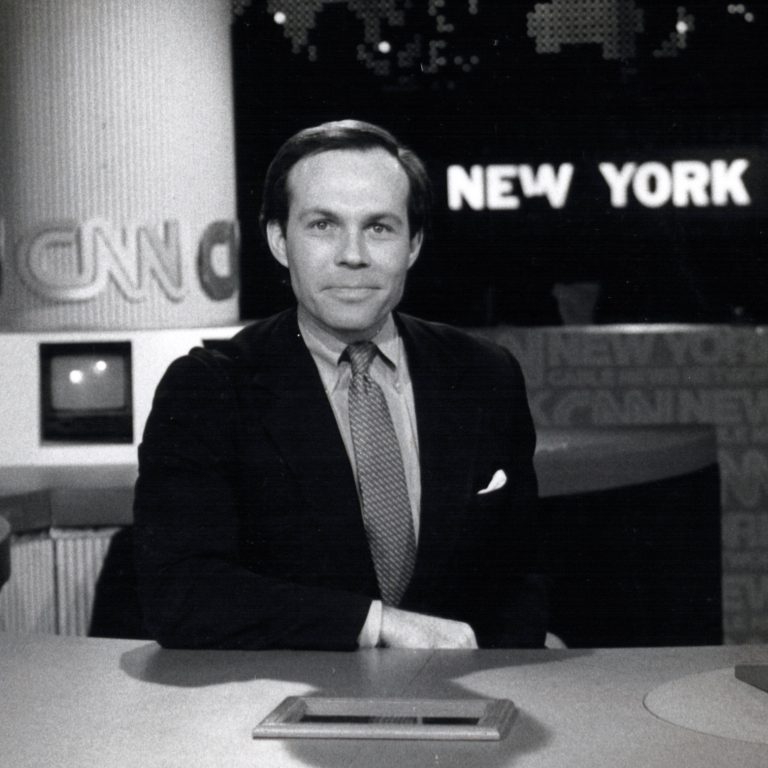

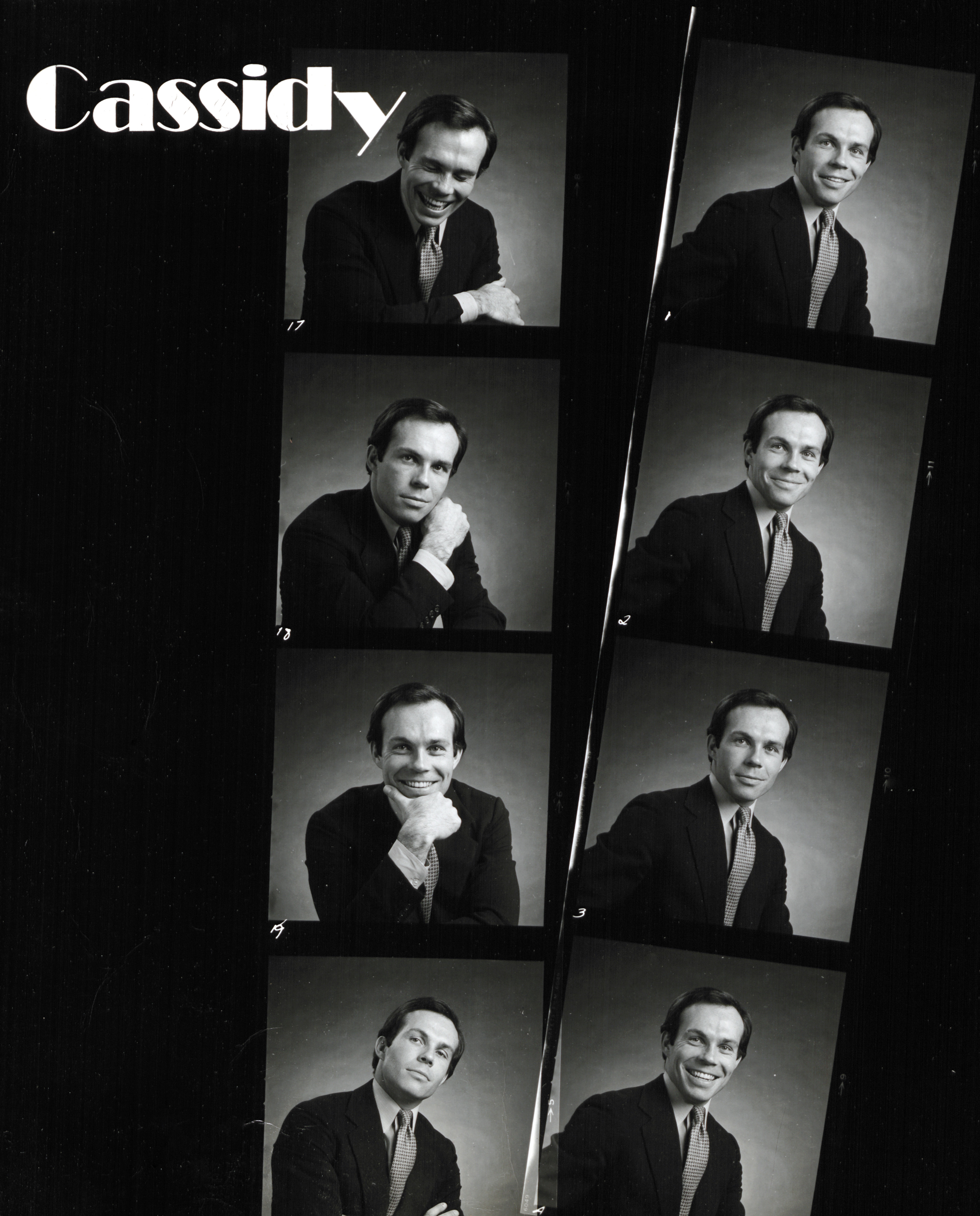

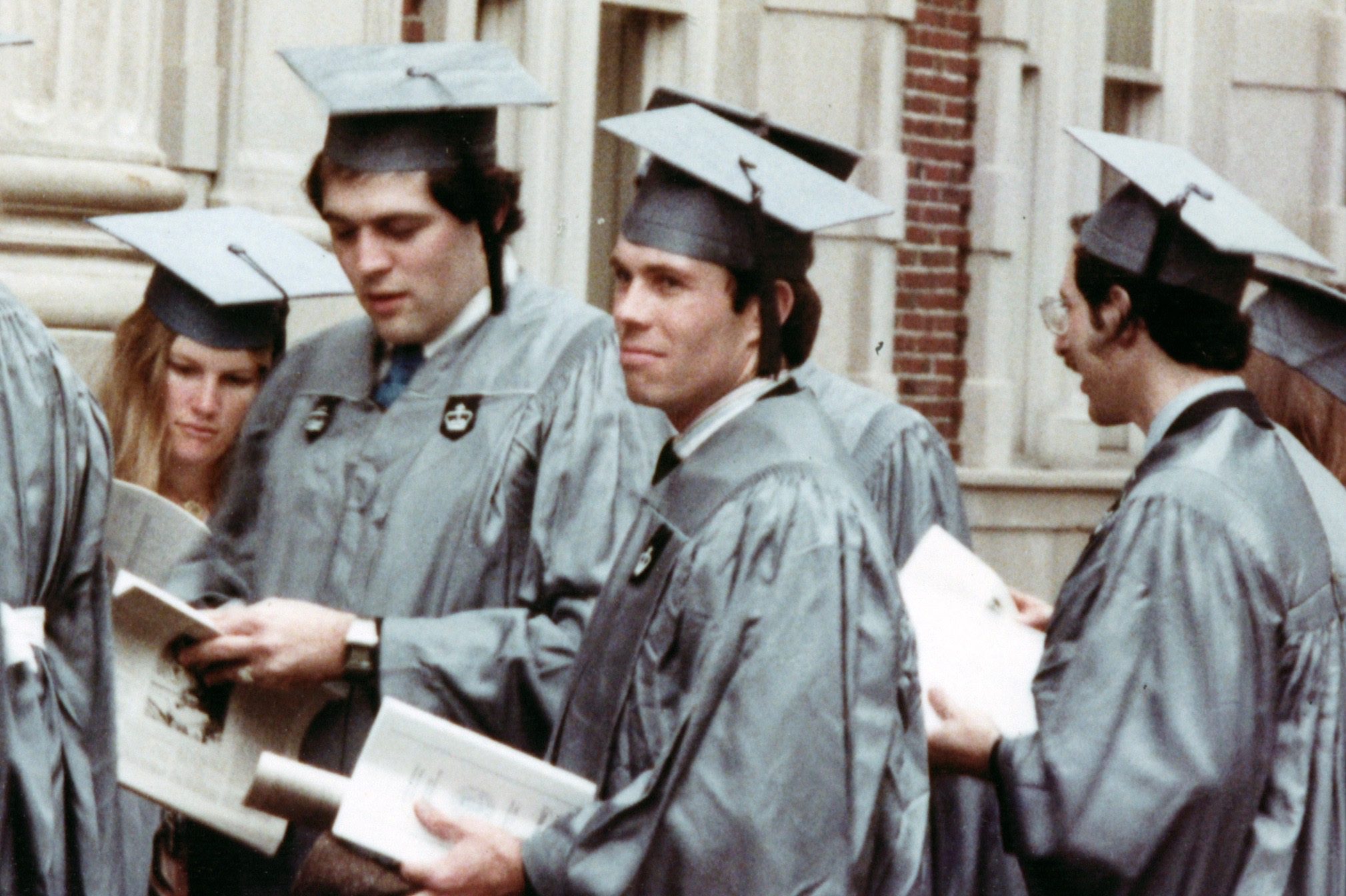

Tom Cassidy on the set at CNN, mid-1980s. Credit: Courtesy of Whit Raymond.

Tom Cassidy on the set at CNN, mid-1980s. Credit: Courtesy of Whit Raymond.Episode Notes

For the first decade and a half of the AIDS epidemic, before there were effective treatments, AIDS rewrote the unwritten rules of the closet. Because AIDS was inextricably tied to gay men—the vast majority of those who were struck down by the disease in the United States during this time were gay men—tens of thousands were forced out of the closet as they sickened and died.

Tom Cassidy knew the rules of the closet. As he built his career from local TV reporter to CNN business news anchor and host of that network’s “Pinnacle” series, Tom kept his gay life and his professional life strictly separate. And then he found out he was going to die.

Unlike some gay men diagnosed with AIDS whose high-profile careers led them to disappear from public when they became seriously ill, Tom Cassidy chose the opposite course. He decided to bring his experience into the living rooms of viewers through a three-part television series produced by journalist Mike Taibbi for WCBS-TV, New York City’s CBS affiliate.

As Tom told MGH host Eric Marcus in his 1990 interview, “I wanted to do some good. I really wanted to make a political statement as a gay person, as well as an AIDS patient… I thought I could make AIDS patients feel better. I could make the public understand that some of their TV newsmen are gay and sick… Everyone identified me as one of the good guys, and there are millions of people who have seen me on television. I wanted them to know that a favorite of theirs could get this disease—and, secondarily, that he happened to be gay. I also thought that maybe I could help show people that AIDS is not just a gay problem. When gay people die of AIDS, the whole society is so much poorer…”

To learn more about Tom Cassidy and the AIDS epidemic, please have a look at the resources, links, and photographs that follow below.

———

Tom’s appearance in the WCBS-TV three-part television series led to many additional media interviews, including this article in People magazine.

You can find Tom Cassidy’s oral history in Eric Marcus’s book Making Gay History.

The New York Times published Tom’s obituary on May 29, 1991.

Tom left money in his will to Bowdoin College to establish the Tom Cassidy Lectureship in journalism, which continues to this day. Guest lecturers have included Tom’s former boss Lou Dobbs, NPR’s Linda Wertheimer, and David Brooks of the New York Times.

In the same year that Tom came out about his AIDS diagnosis, a former KGO-TV reporter in San Francisco, Paul Wynne, sold his one-time employer on the idea of producing a weekly chronicle of his life as an AIDS patient. You can read about Paul and the series here. You’ll find his New York Times obituary here.

Author Larry Gross provides a solid overview of LGBTQ people in relation to mass media (prior to 2001) in his book, Up from Invisibility: Lesbians, Gay Men, and the Media in America.

NLGJA (originally knowns as the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association) was founded in 1990 by openly gay newspaper editor Roy Aarons. It’s an organization of journalists, media professionals, educators and students working from within the news industry to foster fair and accurate coverage of LGBT issues. NLGJA opposes all forms of workplace bias and provides professional development to its members. To learn more, click here.

To learn more about the AIDS epidemic, read And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts and How to Survive a Plague by David France. David France also directed a documentary of the same name.

In June of 1993, New York Times reporter Jeff Schmalz wrote reviews of two other documentaries about AIDS that we recommend: Silverlake Life and The Broadcast Tapes of Dr. Peter. Jeff, who wrote in the New York Times about his experience of having AIDS (and died from complications of the disease in November 1993), was himself the subject of a recent audio documentary called “Dying Words.”

———

Episode Transcript

I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

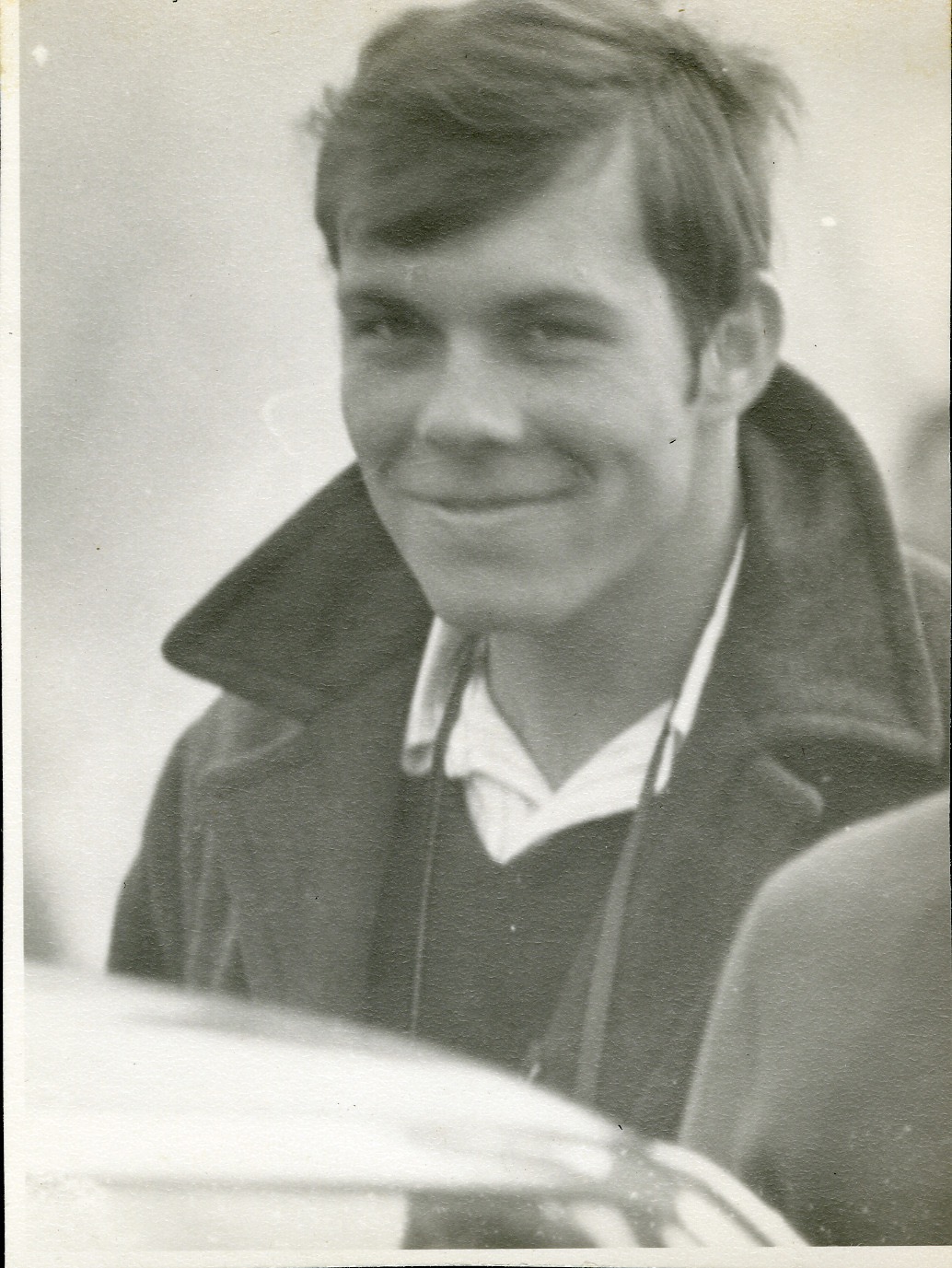

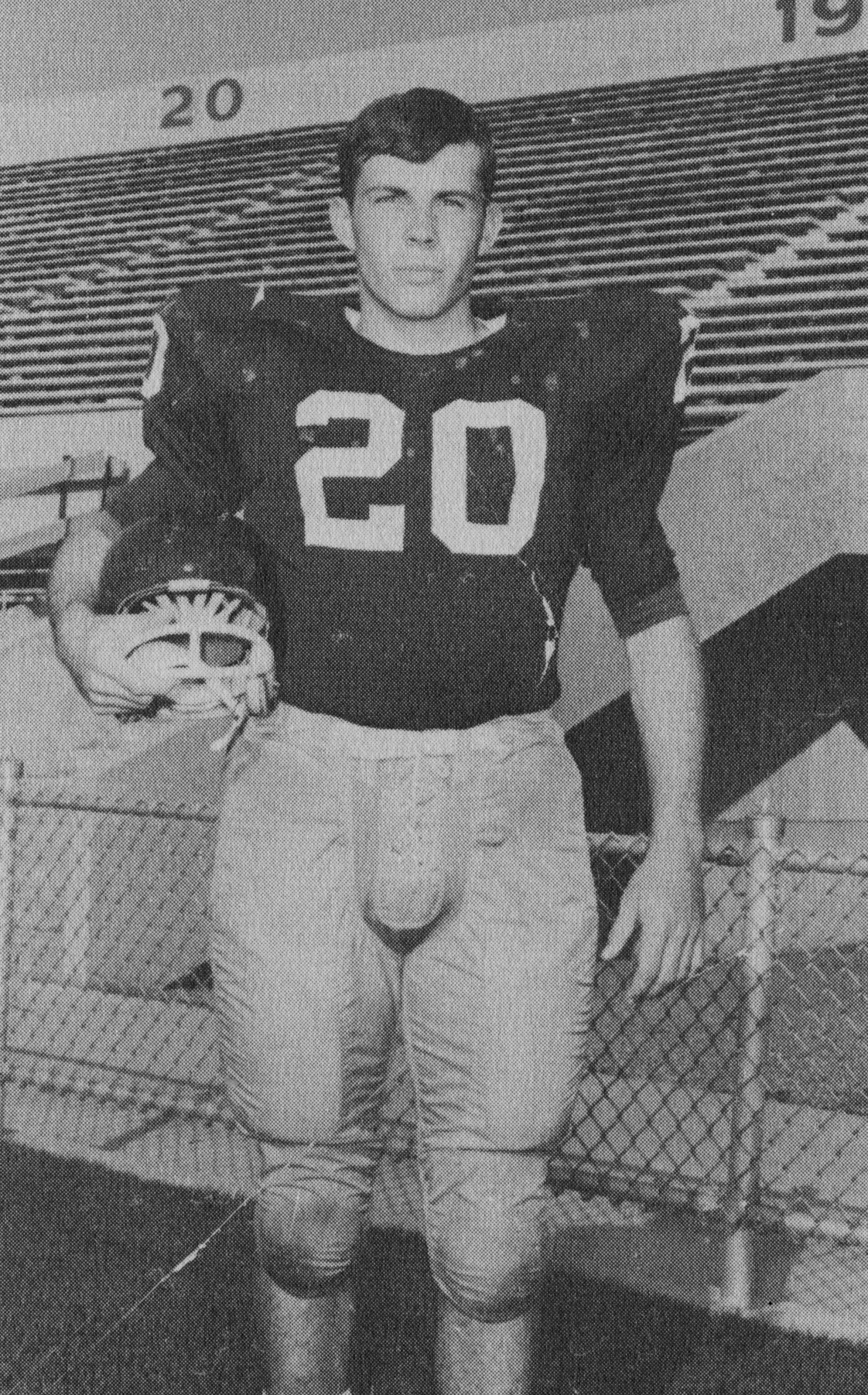

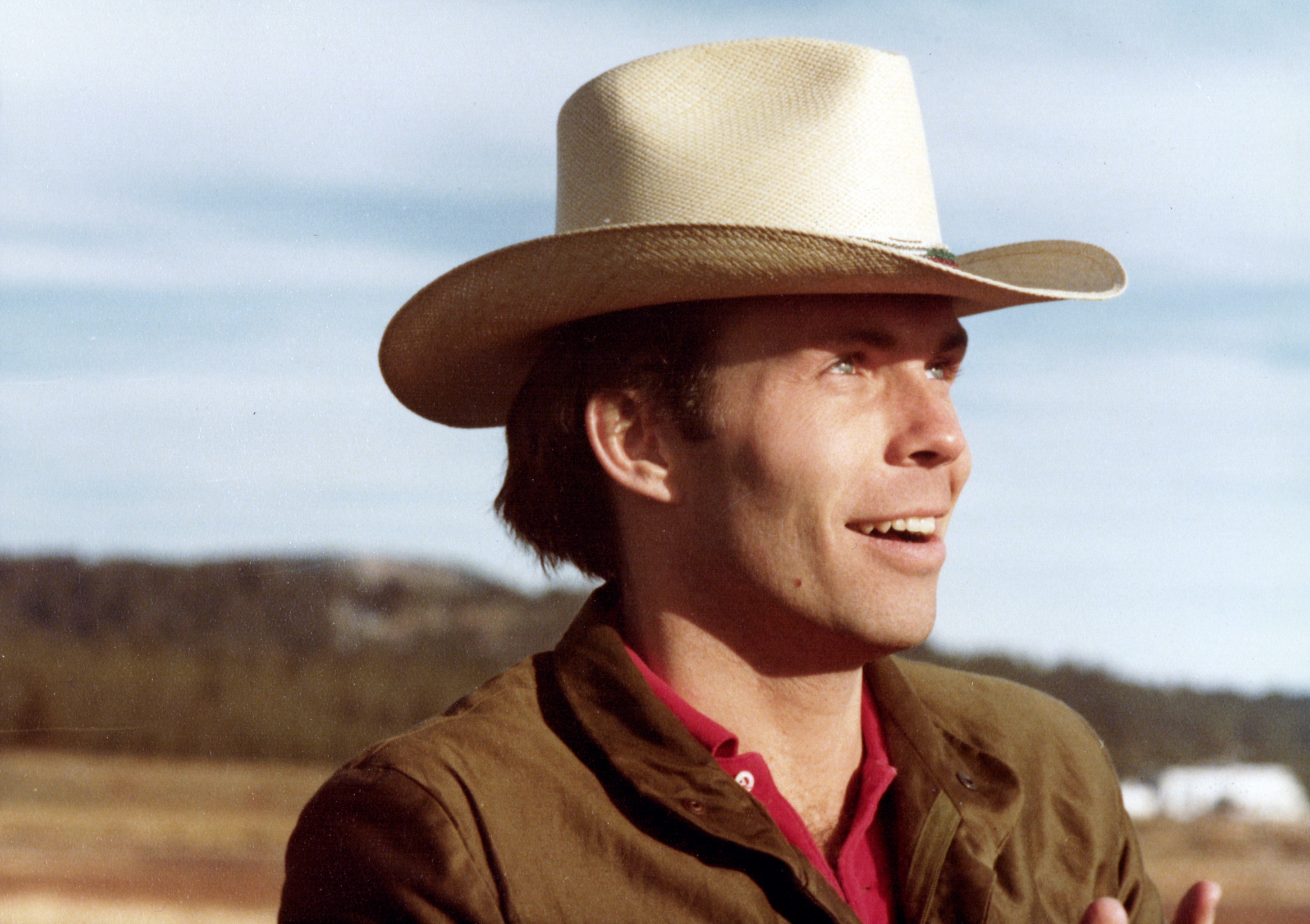

Tom Cassidy was a total alpha male. Athletic, smart, in charge. And proud of the way he’d worked his way to the top despite growing up poor in a Boston housing project. His alcoholic, abusive father abandoned the family when Tom was two-and-a-half.

Tom earned a football scholarship to the University of Massachusetts and after his freshman year muscled his way into Bowdoin, an elite liberal arts college in Maine. He followed four years there with joint masters degrees in business and journalism at Columbia University.

And then he set his sights on TV journalism. By 1983 Tom was a rising star at the three-year-old Cable News Network where he was a business anchor and host of CNN’s “Pinnacle” interview series. He had status, respect, and financial security. And he loved his job, even though that meant hiding the fact he was gay. Back then, almost all gay people who worked in journalism—and virtually everyone who worked in front of the camera—kept their private lives very private.

Tom’s peak professional moment came on October 19, 1987, when he anchored CNN’s coverage of the Black Monday crash as stock markets around the world plummeted. It was the single largest percentage drop for the Dow Jones Industrial Average in its history. And Tom provided a calm, steady voice on a day when both were in short supply. It was also the day he found out he was HIV-positive.

So here’s the scene. It’s the fall of 1990. I arrive on the 20th floor of CNN’s headquarters in New York City. The newsroom is buzzing. I’m escorted to Tom’s private office by an assistant. He steps from behind his desk and shakes my hand, which disappears into his.

Tom looks older than he does on television, but knowing he’s had two close brushes with death, I’m surprised by how good he looks. At 41 he still has the solid build of a college football player and a boyish, disarming smile. His face is lined and a bit gaunt—the skin tight around his well-defined cheekbones. His brown hair is thinning, but his blue eyes dazzle. I’m just a little bit smitten.

Tom motions for me to close his office door and sinks into his padded chair. I reach across his desk and clip my microphone to his tie. He gets a few coughs out of the way before I press record.

———

Interview Date: Monday, October 8, 1990

Eric: Tom Cassidy at CNN in New York City. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Tom: It had become crystal clear to me that I was in love with my roommate. And we talked about it.

Eric: Your roommate was straight.

Tom: Yeah.

Eric: Was he also a football player, also?

Tom: Yup. He was football, hockey. He was a very good athlete. Yeah. Whit.

Eric: How’d you break it to him that you were in love with him?

Tom: I just told told him that essentially. And he was very understanding about it.

Eric: Was he the first man you fell in love with?

Tom: This was a mature, a maturing love that I was feeling for the first time.

Eric: As opposed to a crush.

Tom: Yeah, I’d say so.

Eric: That must have been very frustrating.

Tom: It was very frustrating. And when we graduated, he hoped to go to medical school. So I just left altogether and I went to Europe for almost a year and just traveled.

Eric: What did you find?

Tom: Part of it, well, that’s really kind of where I came out. I remember meeting this American in London. I didn’t know what to do. I really didn’t. I didn’t know what to do. We go back to my place in London and we proceed to chase each other around and, during the process, the pillow falls off the bed and goes into this heater and catches fire. You want to talk about interruptus. That was really very frightening. Then…

Eric: Was it the Catholic god come to…?

Tom: Probably.

Eric: You think that?

Tom: Well, maybe a little guilt, but it’s a guilt that’s mixed with excitement, you know. And that had been really the first time.

[Knock at the door.]

Eric: One second.

Tom: Come in.

Unidentified person: Hi, I’m sorry to interrupt you.

Eric: Do you need to…

Tom: I gotta do an update.

[Tom removes his microphone, departs, then returns.]

Tom: There.

Eric: Um, so you came back.

Tom: Um, hmm. I moved here to New York and I went to work for Reader’s Digest, the publishing side of Reader’s Digest. I really thought all the fun was being enjoyed on the editorial side. But I wasn’t prepared for it. I decided that I would go to graduate school in the business school at Columbia and also the Journalism school at Columbia.

And at the time, I got involved with somebody, John Woods, he was 12 years older. He was an illustrator. And he was real jet-set New York. And it was just a blast.

John was somebody I had known for five years when I graduated from the schools. And my choice was Eugene, Oregon, or Butte, Montana, to get started in television news. I go to Eugene, Oregon. Nine months later I go to San Francisco. Nine months later I go to Chicago. Right when I landed in Chicago, you know, John took the wrong person home and he ended up having a dreadful death. He was murdered.

Eric: And he was still your lover at that point?

Tom: Well, we talked all the time, yeah. He really kind of was. We were very close. We talked a lot. It happened about two months after my mother had suddenly died of a stroke. I had lost the two most important people in my life.

I remember the general manager of the station in Chicago kind of not wanting to let me go to the funeral because I had only gotten there three days before. He said, “You’ve just started here.” He goes, “It’s not family.”

Eric: Did he know who he was to you?

Tom: No. So I just turned around and I said, “It’s not negotiable,” and I walked out. And I went to Duncan, Oklahoma, where John was buried. And I was right between the mother and father.

Eric: They knew who you were to him.

Tom: Yeah. They did, although it was never really discussed, yeah. Then I just sort of came back to Chicago and was the business editor for Mutual Broadcasting in WCFL there. I couldn’t grieve in any public way. And I was in shock and I couldn’t talk to anybody about it.

Eric: How hard was it to stay in the closet then at work?

Tom: It wasn’t difficult for me at all. I almost have felt like I have a mechanism that I can really separate work from play. And I did not… I made a point of not really socializing with people that I worked with. Once you make a decision and you get a habit down.

Eric: And you were good at it.

Tom: Very good at it.

Eric: When did you first think you had AIDS?

Tom: It all happened kind of quickly. I tested positive the day of the stock market crash in ‘87.

Eric: October 19th.

Tom: Right. And then I started to have to think more about it, what all this meant, testing positive.

Eric: Were you surprised?

Tom: Yeah, kinda, because I felt good and I was traveling 200,000 miles a year and being the attack dog reporter here in the money market area. And I was just going full speed. And I eventually had pneumonia in July.

Eric: And you couldn’t come to work with that.

Tom: No, what was funny was I had taken a week’s vacation just before and gone out to Fire Island to shake this cold, I thought. And I came back and called my doctor and he said I should come to see him that afternoon. And it was classic pneumocystis [pneumonia]. And he said, “Do you know what that means?” And I said, “AIDS?” My instinct was, “I have to go back to work!” And he said, “You are to go home and pack a bag and go to Mt. Sinai.”

Your life changes in such fundamental ways when that word comes to you. I felt terrible, terrible! And I was a jock and I had never felt terrible.

Eric: How long were you in the hospital?

Tom: Sixteen days. I mean these fevers were unbelievable.

Eric: You must have been scared.

Tom: I was scared. I was scared in that I wasn’t prepared to die. It was such a shock. And it was kind of rude. It really was. I mean I hadn’t said goodbye to anybody. Nobody knew what the situation was.

Eric: It wasn’t your time.

Tom: It wasn’t my time. Exactly. And I’m certainly supposed to not just suddenly die.

And I came back to work. They put me on the air the first day back. And I looked very skeletal. For, gee, a year-and-a-half, a solid year-and-a-half there were probably a maximum of six people in my life that knew I was sick. I was popping those AZT and going to work every day and feeling wobbly. And the camera doesn’t lie. And so you had extra make-up. Eventually I became so anemic I had nine transfusions. And I would go and get the transfusions and then rush to work. And I eventually came off AZT…

Eric: Because it was making you so sick?

Tom: Too anemic, yeah. And they put me on DDI and everything was going hunky-dory from January…

Eric: Of this year…

Tom: Yes, until April. And on Easter Sunday, I was in Boston and I started to not feel right. My stomach. I was really hurtin’ right there. And I jumped in the shuttle, came down. So I get down here and I go to my house and call my doctor. And he gets back to me in like 15 minutes. He said, “You are to meet me in Mt. Sinai in 20 minutes.”

I went into the emergency room. And as it turns out my pancreas was six times normal size. They did not know for the next six days whether I was gonna make it. You can’t eat or drink a thing and your pancreas makes up its mind whether it wants to live.

Eric: So how did the truth make its way out?

Tom: Well, that was actually kind of funny.

Eric: Because none of this is funny.

Tom: It isn’t, but I always had a good sense of humor.

Eric: Good thing.

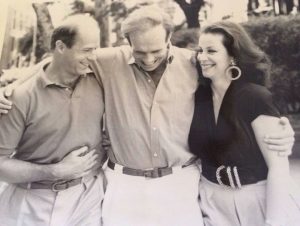

Tom: I’ve always had a good sense of humor. Before I left for the Mt. Sinai emergency room, like a responsible reporter, I had called the assignment desk and said I would not be in tomorrow. This message for some reason got lost. So, on Monday, they can’t find me here. They called the police. They called the FBI. They ended up calling morgues. Then they called my sister. And my sister calls my college roommate.

Eric: Whit.

Tom: Whit.

Eric: With whom you’re still friends.

Tom: Very much so. And he was one of the few people who did know I was sick. And he remembered that when I was sick the first time with pneumonia, I was in Mt. Sinai. And Whit calls me in the hospital and I answer the phone. I said, “Hi Whit, how are ya?” And he goes, “What am I supposed to tell Lorraine?” My sister. And I said, because I was hurtin’, I said, “Tell her everything. Everything!” And he said, “Are you sure?” I said, “Uh, huh, yeah.” And, so, he told her and she called me 20 minutes later. She was great.

Eric: When did they find out here at the office?

Tom: When I came back to work my boss, Lou Dobbs, asked me to come into his office. And he said, “How are you doing?” And I said, uh, I was trying to put the best foot forward, and said “Great. Great.” And he said, “How sick were you?”

Eric: Were the beads of sweat on your forehead at that point?

Tom: Yeah. And I said, “Well, I was pretty sick.” And he said, “Well, how sick?” I said, “I was very sick.” And he said, “How sick?” And I said, “Well, I have AIDS.” And his eyes just sort of rolled back.

It was very much a feeling of relief for me, because Lou Dobbs is clearly one of the most important people in my life. Almost, clearly a brother figure. He’s a western cowboy, a macho homophobe, who was really a very good friend of mine. And I was afraid of what his reaction would be.

Eric: Because of the AIDS or because of being gay?

Tom: Both. He totally surprised me. I did not have any negative reaction from him. He said, “What do you want me to do?” He said, “Do you want me to tell anybody or do you want me not to tell anybody?” I said, “I think you better tell everyone.”

Eric: Why at that point?

Tom: I was tired. I was tired of living a lie.

Eric: About AIDS?

Tom: And also about being gay. Because they were intertwined at that point. And he scheduled a meeting for the whole department. And he told them. I wasn’t around.

Eric: That must have been very hard.

Tom: It was very hard for him.

Eric: For you, as well.

Tom: Well…

Eric: Or was it simply comforting?

Tom: It was almost comforting.

Eric: Did they surprise you?

Tom: Oh, yuh.

Eric: What did you expect?

Tom: I didn’t know.

Eric: What did you fear?

Tom: Rejection and people freaking…

Eric: Because of…

Tom: Because I had AIDS, first of all. That’s not an easy message to get and to be around.

Eric: And you’re a prominent figure within the company.

Tom: Very prominent, yeah. And I’ve been here a long time. And I came in the next day…and…you know, there were flowers… and mass cards… and a lot of messages. There was a lot of love. And my life hasn’t been the same since.

For the last two years I had lived a very difficult, fabricated life. I used to have to sneak home sometimes and lay down during the day when I had some time off.

Eric: So you had a double closet.

Tom: Yeah, exactly.

Eric: It was not as if you had some disease that you could extricate from the fact you were gay.

Tom: Right. Plus, I mean, I could… I suddenly became very tuned in to what was going on with the plague and it wasn’t lookin’ good. And I had to think about dying. I’m still trying to figure out, like a peripatetic reporter, what happens next. I mean, when you close your eyes, I mean, take your last breath, what happens? I haven’t gotten figured out.

Eric: You can’t take a notepad or a television camera so you can… It’s all on your own.

Tom: You know, you don’t hear from people… I don’t hear from people that have passed away. So I don’t know. It’s kind of intriguing, in a way.

Eric I wonder if there are gay people in heaven.

Tom: Oh, I think so. I think so. Maybe heaven is one big gay bar.

———

Tom Cassidy had reason to be surprised by how his colleagues rallied around him. It was 1990, and effective treatments for AIDS were still years away. Back then many people were actually afraid to be around someone who had AIDS.

After Tom went public with his diagnosis at CNN, he jumped at the opportunity to be the focus of a TV series about AIDS for New York City’s CBS News affiliate. Tom told me, “I make my living essentially being a face. What I decided to do was to lend that face to AIDS.”

Tom had a chemotherapy infusion following our interview, so I rode along with him to his doctor’s office on the Upper East Side. As soon as we left his office at CNN, I could see how unsteady he was on his feet, but I really resisted taking his arm because I knew he didn’t want anyone’s help. At 85th Street we parted with a hug. Tom said to stay in touch. In my notes from that day I wrote, “I wonder how long he has.” It turned out he had seven months and I never saw him again. Tom Cassidy died on May 26, 1991. He was 41 years old.

Tom’s name lives on at Bowdoin College where he endowed an annual lecture series that brings working journalists to the school’s campus. The first lecture was given by Tom’s CNN boss, Lou Dobbs, and in the years since, speakers have included NPR’s Linda Wertheimer, David Brooks from the New York Times, and Ben Bradlee and Sally Quinn from the Washington Post.

———

This is our final episode of season two, so please stay tuned for season three, coming this fall. To get the latest news on our plans for Making Gay History and upcoming events, please sign up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. That’s also where you can find photos and additional information about Tom Cassidy and where you can listen to all our previous episodes.

Before I say my final thank-yous, I want to share an email with you. At the end of a recent episode, I told you that whenever I spoke with legendary octogenarian activist Kay Lahusen, she greeted me by saying, ”Hello dear. What have you got for me?” So I invited you to write to me so I could pass your message on to her. This one jumped out at me:

Hello,

I just got through listening to your podcast on Kay Lahusen and Barbara Gittings. You closed with a reference to Kay’s question “What do you have for me?” Well, here’s something. I am the proud father of a beautiful young woman named Annika. She is 17 years old and dating a most spectacular young lady. She is totally at ease with who she is, quite open about her life, her love and personality. Indeed, she and I just finished shopping for a prom dress in anticipation of when she and Mattie go to the prom this spring.

I have to credit the work and bravery of Kay and Barbara for that. Here, in of all places, Laramie, Wyoming, my daughter loves another young woman and she is totally at ease with that.

Tell Kay thank you for me, for Annika and for Mattie.

Charles F. Pelkey, Minority Whip, Wyoming House of Representatives

Kay loved all the emails, which I read to her by phone and she asked me to thank you for your thoughts and love. And feel free to keep them coming. Write to me at hello@makinggayhistory.

———

I’m beyond grateful to the many people who have made Making Gay History possible. Thank you, Kevin Jennings, for the Arcus Foundation grant that got us launched. We’re grateful, as well, to Barbara Raab, a program officer at the Ford Foundation, who made the funds available for Making Gay History’s second season. And then there’s our crew. Sara Burningham, our executive producer, always finds a way to make the Making Gay History voices sing. Jenna Weiss-Berman, our coproducer from Pineapple Street Media, believed in us before we believed in ourselves.

Thank you also to audio engineer Casey Holford; researcher Zachary Seltzer; our website designer Jonathan Dozier-Ezell; and social media strategist Will Coley. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

And finally, thank you to my partner in life, Barney Karpfinger, who never doubted that the little podcast that could, could.

Making Gay History is a coproduction of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives Foundation.

Season two of this podcast is made possible with support from the Ford Foundation, which is on the front lines of social change worldwide.

So long. And we’ll see you in the fall.

———

Tom: 1275. Tom Cassidy from CNN. 5 Penn Plaza. 85th and Park—85th and 5th. 7147907. Yes, okay, great. Thank you. Now I have to go take some real serious drugs.

###