Jean O’Leary — Part 1

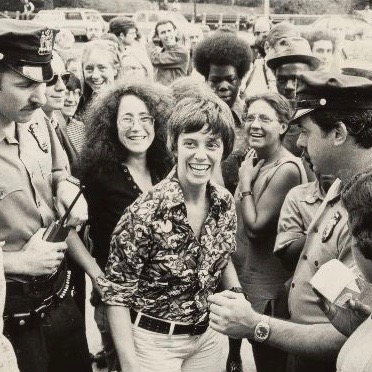

Jean O'Leary at the Museum of Natural History in New York City, August 1973. Credit: © Bettye Lane, courtesy of Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute.

Jean O'Leary at the Museum of Natural History in New York City, August 1973. Credit: © Bettye Lane, courtesy of Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute.Episode Notes

Jean O’Leary was passionate—about women, nuns, feminism, and equal rights. She left an indelible mark on the women’s movement and the LGBTQ civil rights movement, but not without causing controversy, too. After all, she was a troublemaker. And proud of it.

Episode first published March 23, 2017.

———

Jean O’Leary planned to be a nun, but her experiences at a Cleveland convent propelled her into a very different life. After moving to New York City in 1971, O’Leary became one of the leading voices in the LGBTQ civil rights movement. A passionate advocate for women’s rights, she founded Lesbian Feminist Liberation in 1972 and two years later joined the National Gay Task Force (now the National LGBTQ Task Force) as co-executive director.

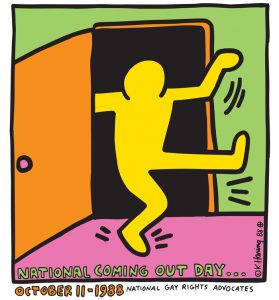

O’Leary is perhaps best known for two key events: she organized the first meeting of lesbian and gay rights activists at the White House on March 26, 1977 (this historic meeting is the focus of part 2 of O’Leary’s interview, which is featured in this episode); and she cofounded the annual National Coming Out Day, which was first held on October 11, 1988.

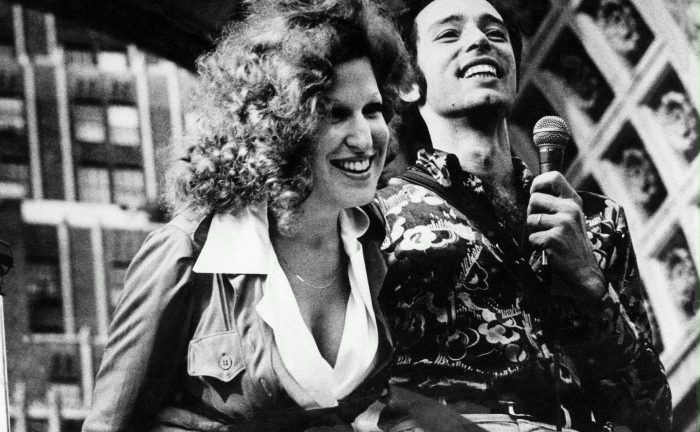

In this episode of Making Gay History, O’Leary discusses a confrontation between her and trans activist Sylvia Rivera—another event for which she is remembered. The confrontation took place at the 1973 Christopher Street Liberation Day rally in Washington Square Park in New York City’s Greenwich Village. The photo below is from that event, which was emceed by Vito Russo. (You can listen to Vito Russo’s MGH episode here and Sylvia Rivera’s episode here.)

Here’s the story behind the photo as told to Eric Marcus by Vito Russo: “The rally used to be a battleground for ideas and politics. I knew that the tensions would be running high that day because a group of radical lesbians were opposed to a couple of comic drags scheduled to be a part of the entertainment program. Drag was high on their hit list. So I began working on Bette Midler weeks in advance to come and sing to sort of calm things down. Well, the lesbians heckled the drag queens throughout their numbers, and when it was over, Jean O’Leary got up and made a very angry speech in which she said that men who impersonate women for profit insult women. All hell broke loose in the audience between the men and the women, and Bette got up on stage and sang ‘Friends.’ She had brought Barry Manilow with her. Bette worked like a charm. It wasn’t that the issues were forgotten, but she provided a tremendously healing presence. It was a great thing for Bette, too. She said later that it was one of the great things she did, that she felt like she was Marilyn Monroe singing in Korea.”

———

For an overview of Jean O’Leary’s life, read this article by Linda Rapp. O’Leary’s oral history is included in the first edition of Eric Marcus’s Making Gay History book (titled Making History).

O’Leary wrote about her experiences at a Cleveland convent in the 1985 anthology Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence.

The audio excerpts of O’Leary and Sylvia Rivera speaking at the June 24, 1973, pride rally in New York City’s Washington Square Park that we included in the episode were taken from videos recorded by the L.O.V.E. (Lesbians Organized for Video Experience) Collective. Members of the L.O.V.E. Collective include Betty Brown, Delia Davis, Tracy Fitz, Blue London (Doris Lunden), Barbara Jabaily, and Denise Wong. You can watch Sylvia Rivera’s entire speech here.

In 1972, O’Leary founded Lesbian Feminist Liberation (LFL), a lesbian rights advocacy group. In 1973, LFL organized a protest against New York City’s American Museum of National History for its erasure of women’s history and culture. Read about the demonstration—which involved a giant lavender papier mâché dinosaur named Sapphasaura—here.

National Coming Out Day (NCOD) was founded by O’Leary and Robert Eichberg in 1988. A history of NCOD can be found here.

Watch O’Leary’s 1989 address, “From the Margins to the Mainstream,” here.

O’Leary’s 2005 New York Times obituary can be found here. Gay City News published a more comprehensive obituary here.

———

A Remembrance of Jean O’Leary from Her Friend Sean Strub

After listening to the episode, the writer and activist Sean Strub emailed MGH to share his memories of his dear friend Jean O’Leary:

Jean was one of my very closest friends from around 1985 until her death. I did NGRA [National Gay Rights Advocates]’s fundraising mail and wrote many of her public comments about the epidemic, at the DNC, etc. Both of my younger sisters, at different times when they were in their early 20s, attended the annual Women’s Dance Jean organized in Los Angeles for the LA Center, as her guest.

At the War Conference in 1986 or 1987, she and Rob [Eichberg] took on the task of urging people to come out and it was initially designed as an ongoing program (not establishment of a “day”), to kick off in DC that year when the Quilt was on display.

A few months before, we were discussing when over the weekend we would have the coming out program with some prominent people who had agreed to participate. The question was which day of the weekend should we pick—it could have been Friday, Saturday or Sunday; other activities planned for the weekend could have worked around our much-hyped celebrity coming out. I suggested October 11, which was Cleve [Jones, founder of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt]’s birthday, as a surprise and honor to him, since the quilt was the major attraction and the impetus for the coming out event in DC that weekend.

Jean and I had long phone conversations, sometimes spanning several hours, spent a number of holidays together, including the Thanksgiving right before my partner Michael died. When I stayed with her when I was in LA we would sit in her bed watching TV and talking and doze off, several times spending the night in the same bed. I’m wistful even thinking about it. She left her papers to me, because she knew I would treasure them and find a good home for them. I hired professional archivists right after she died, to sort and organize them, and recently they went to the Beinecke Library at Yale, in New Haven.

I’ve considered Jean’s activism unique in that she achieved credibility, respect and had a big impact in four distinct arenas: the women’s movement, gay and lesbian rights movement, Democratic Party activism, and AIDS activism. She was most modest about the last of those. Yet it was NGRA’s AIDS Civil Rights Project that was gutsier, innovative and driving much of the litigation strategy on AIDS-related issues in the mid and late ’80s, including their litigation against the National Institutes of Health. The first published demand for a “medical Manhattan Project” to combat AIDS was from NGRA.

For various reasons, including, I believe, stylistic differences, sexism, regional parochialism and fundraising jealousies (by 1987, NGRA had 27,000 donors, more than HRCF, NGLTF, Lambda or any other LGBT group), she became a target, which ultimately led to her leaving NGRA and its eventual absorption into HRCF.

Anyway, thanks for sharing the interview. Her birthday was earlier this month.

— Sean

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

Jean O’Leary was a troublemaker. I don’t think she’d argue with that description. She went to an all-girls Catholic school in Cleveland where she earned a reputation as a cut-up. Jean held the record for the most detentions ever. What she called her “baby pranks” included setting off fire alarms and holding dances in the auditorium during lunch.

Jean also fell in love over and over again, beginning as far back as third grade. She loved girls, plain and simple. In the 1960s, that was anything but simple.

Once Jean came to terms with who she was, she got to work. Her activism in the LGBTQ civil rights movement spanned more than 30 years and took her from a convent in Ohio, to a contentious rally in New York City’s Washington Square Park, to a landmark meeting at the White House.

Here’s the scene. I meet Jean at her office in North Hollywood. First we go to a nearby cafe and then continue our conversation at The Ivy, a very gay-friendly restaurant on the border of Los Angeles and West Hollywood.

Jean is casually dressed in slacks and a blouse. She has thick, brown, close-cropped hair. She couldn’t have been more open and thoughtful. And funny. She had a great laugh. And a dazzling smile. Before I even set up my tape recorder, we are deep in conversation. So we’ll pick up her story after she ran away from a marriage proposal to live in a convent.

———

Jean O’Leary: The convent was great. It was one of the best experiences of my life on every single level. When I got there, I wasn’t there for more than six months when I really did come out. And so I came out sexually. Emotionally, it was incredible. We had a priest who was a therapist, who came in and ran sensitivity groups. And if you want to talk about living in a closed environment and being in sensitivity groups and sort of stripping down the defenses and then going away and living with these same people for 24 hours a day, day in and day out. We were on a villa at the novitiate. And so we didn’t go off that villa either. So the intensity was really intense. We were up to all hours of the night. We would go smoke in the cafeteria. Or, you know, do whatever. And I was always in love. I had like eight relationships when I was in there.

Eric Marcus: Oh, my god.

JO: I know, God was an innocent bystander. In fact, I had an affair with a postulant mistress, which was a very deep affair. At the same time I was having an affair with Bunnie and the priest was involved with the both of them, but not sexually. But it was a real sort of a balancing kind of an act. I went in and told him, I said, “I think I’m a homosexual.” So, anyway, he said, basically, “Well, don’t you think, you know, just because we’re in a same-sex environment, really, and these feelings are just natural and we just have to try to be celibate.” I said, “Great.”

EM: You said…?

JO: I said, fine, you know, but it was so debilitating to me, because I was ready to come out. I was ready to tell the truth and everybody was ready to cover it up again, or he was.

EM: That was your coming out.

JO: It was. Yeah.

EM: Had you even said it verbally to yourself, verbally spoken I mean?

JO: No. No.

EM: You had never spoken the words before.

JO: No. Uh, uh. No. Not with the “I” attached to it. “I am,” you know…

EM: Can you remember, do you remember saying that to him?

JO: Yes!

EM: How vivid is that?

JO: Oh, it’s extremely vivid. And I remember all the feelings afterwards, too. Because it was like, this is it. Then I gotta get out of here because I don’t belong here. I don’t know what I’m going to do with my life, but, you know, this is it. And then I tell him and he, like, glosses over the whole thing because he didn’t want to hear it. He said I was a very interesting person, very vivid, very open. And then he wanted to analyze my dreams. And I’m like, “Oh boy.” So I went out and… I remember going out and sitting in this silo. It was empty. And it just was sort of a personification… not a personification, but an emphasis of what I was feeling in terms of the loneliness, the emptiness, the not being heard, the “Oh, my God, I finally said it,” and this is what I get back.

EM: How did you get from that silo?

JO: How did I get from out of it?

EM: Yes.

JO: How did I? I stayed around for a while.

EM: In the silo.

JO: No, in the convent. I don’t remember how long I was in the silo. But I remember coming out and I remember talking to my friend Linda, who was in her dorm and almost telling her what had happened, but not quite.

EM: You weren’t ready yet.

JO: Uh-uh. Especially now that I’d been saved one more time. Ha. You know? Saved from the truth that I really wanted to… You know, I mean, everybody was in collaboration. It’s like that conspiracy of silence, and even when you’re ready to break out of it, it’s not easy. People don’t want to hear it.

———

EM Narration: Jean did make it out of the silo, and the convent. In 1971 she moved to Brooklyn to a studio apartment that came with a male roommate who turned out to be gay. Together they went to their first Gay Activists Alliance meeting, and that was the beginning of Jean’s decades-long involvement in the movement.

In the end, Jean had no regrets about leaving the convent. But there were other things she regretted in her life. And you’re about to hear about one of those things.

It’s 1973 and Jean is at the gay pride rally in Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. By then she’d led a split of the women from the Gay Activists Alliance and formed a new organization called Lesbian Feminist Liberation.

Jean’s group was protesting the rally organizer’s decision to include drag queens as part of the entertainment. While Jean and other LFL members were passing out flyers to the crowd, Sylvia Rivera took the stage and made her now famous speech.

———

Sylvia Rivera: You all tell me go and hide my tail between my legs. I will not for longer put up with this shit. I have been beaten. I have had my nose broken. I have been thrown in jail. I have lost my job. I have lost my apartment. For gay liberation. And you all treat me this way? What the fuck’s wrong with you all? Think about that. The people that are trying to do something for all of us and not men and women that belong to a white middle-class white club. And that’s what you all belong to. Revolution now!

———

EM Narration: Jean was reluctant to talk about what happened. The Jean I was sitting with outside The Ivy was not proud of what her 25-year-old self had done.

———

JO: This is so embarrassing. You’re not going to print this, are you? You know, I hate this, because, you know, oh, well, anyway…

EM: Let me tell you why it’s important. What it shows is the evolution of thought and how we got to where we are now. Why you think the way you do now. And you didn’t come to where you are now without having gone through all of this.

JO: Okay, just so long as you can really put this in context. I will trust you more as we go along.

EM: The whole book… I have to put the whole book in context, because some of the things people did and said they can’t believe what they said and did.

JO: I know. I mean, this is really something. This was at a time when the sexism was just rampant between men and women in the gay community.

EM: How did the sexism show itself?

JO: Well, it was blatant. The men actually treated women like surrogate mothers, lovers, sisters. The woman’s role should be respected and that’s where you are. There was, uh, very little… few women in leadership positions and they were consciously kept out of them.

Because just as gay people, you know, have to become visible in the society, lesbians had to become visible, because whenever people said “gay,” they always thought about gay men. We sat around, actually, for months and tried to figure out what were the women’s issues that were different from feminist issues, or different from gay issues. And, quite frankly, to this day no one has been able to come up with what those issues are. But it’s a matter of attitude. It’s a matter of positioning. It’s a matter of respect. It’s a matter of power. It’s a matter of all those types of things, which are a little more subtle. And, um, so, what… and visibility, of course, visibility. Just having people realize that there are lesbians in the world and when you say “gay” it has to include gay men and women.

So, I guess the thing with the transvestites—I would never do this now—but in those days, it was like, well, here’s a man dressing up as a woman and wearing all the things that we’re trying to break free of.

EM: Such as?

JO: High heels, girdles, corsets, stockings, you know, all the things that were just sort of binding women. And, um, so we just decided to make a statement.

We stayed up that night and typed up this little statement on the typewriter. We actually worked all night on it and I’m sure it was just some small statement. Because we were knocking out theory at that time. So it wasn’t just like we were, you know, writing off a paragraph of something. We were actually creating theory. The discussion was, well, but there are laws on the books in the state. If a person had on more than three items of clothing of the other person’s sex then they could be called on that. And so they said, well, that must mean the women, and we could all be thrown in jail for cross-dressing and so we really shouldn’t criticize. We should try to kind of support this kind of thing. So then we decided that, okay, well, we’re not going to attack cross-dressing. We’ll attack men who do it for profit as opposed to do it for a statement.

So, Vito Russo was a very good friend of mine. And we had a falling-out over this issue but he was still trying to be… trying to accommodate. Actually I think he helped me come up on the stage because I was not scheduled as a scheduled speaker. So I got up there…

EM: On the stage.

JO: On the stage.

EM: In front of how many people?

JO: Oh, I mean, you know, tens of thousands, whatever it was. It wasn’t, you know, the 200,000 we have nowadays, but it was quite a few. And I remember, then I got up there and this is a little hazy. I don’t remember the whole thing. Because you’re in the situation…

———

JO: Lesbian Feminist Liberation negotiated for a week-and-a-half using the means that rational women and women have always used in the past, not disruptive means, to try to get up here and read a statement. We were told no, that there would be no political statements read today. Because one person, a man, Sylvia [Rivera], gets up here and causes a ruckus, we are not allowed to read our statement. And I think that says something right there. Now I’d like to go on and speak, but I have written here a statement that’s backed up by a hundred women and this was voted on so I’m just going to read this statement.

———

JO: So, I read the statement…

EM: What did you say?

JO: Well, that we at the Lesbian Feminist Liberation protest the cross-dressing of men in women’s clothes for purposes of profit and we wanted to make that statement clear.

———

JO: When men impersonate women for reasons of entertainment or profit, they insult women. We support the rights of every person to dress in the way that she or he wishes. But we are opposed to the exploitation of women by men for entertainment or profit. Men have been telling us who we are all our lives. They have tried to do it with scholarship, with religion, with psychiatry. When all else fails, they have used humor to tell us and each other who and what we are. What we object to today is another instance in which men laughing with one another at what they present as women by telling us who they think we are. We don’t want to know. Men have never been able to show us ourselves. We are coming into a time and a place as women in which we can and will show one another who we are. Let men tell each other what they think of women. Let us tell you who we are.

———

JO: There was an incredible reaction. A lot of hostility. Men and women started fighting with each other out in the crowd.

EM: Physically or verbally?

JO: There was some physical. There was a lot of verbal. I don’t know what happened after that. I remember leaving.

EM: I can tell you what happened.

JO: Okay, what happened?

EM: Another drag queen got up on the stage, who was livid, and referred to you as “those bitches,” I believe.

JO: Maybe that’s what started the fight.

EM: He said, “The queens started the Stonewall riot and you’re not going to kick us out of the movement.” Do you recall him getting up there at all?

JO: Vaguely, now, I do, vaguely. I don’t have a picture of it, but I do remember that. I remember getting off the stage and walking through the crowd. I was alone for some reason. And, um, everybody had gone every which way and I guess we were going to meet over at Bonnie and Clyde’s, which was right around the corner. And we went in there to meet. And I think that’s where we heard that Bette Midler had come down to sort of smooth things over and sing, you know, “You Gotta Be Friends.” And how did that happen? I don’t think I was there to see her actually do that because I don’t recall it. I just was like, “Okay, bye.” It wasn’t that I was running away from it. But I remember I was out of there. It’s like I had done my thing and now let’s get out of here. Let’s leave. This is hard.

EM: Looking back on it, why are you embarrassed by that now?

JO: Um, because I have since then, I mean, I’ve gone… During the Anita Bryant campaign, for instance, down in Dade County, Florida, I used to go down there and help them with the campaign. And I’d stay at the Windward Hotel, which was just full of transvestites, transsexuals, wonderful, darling, lovable people that I got to know as people and got to know their lives and their stories. And who they are. Why they were. And, you know, just as you grow older, first of all, you learn more and you mellow in terms of your precision about what has to be exactly right and politically correct.

And right now I have… I like… It’s hard even to be tolerant for myself of exact political correctness. And I know that I went through it and I have to have patience with the people that come up now that are going through the same thing, because it’s a process. It is a process.

———

EM Narration: Later Jean said to me, “How could I work to exclude transvestites and at the same time criticize the feminists who were doing their best back in those days to exclude lesbians?” She was right.

If you haven’t heard it yet, go back and listen to the very first episode of season one, my interview with Sylvia Rivera, where she talks about the anger and hurt she felt that “her people” were sidelined in the movement.

I spent a lot of time talking with Jean during two visits back in 1989 and 1990. There were many stories to choose from. And that’s why we’ll be back soon with a special extra episode about when Jean took the first group of gay rights activists into the White House in 1977. It’s a little hard to imagine now, but it was national news. I’ll also be sharing a couple of secrets with you about that meeting that have never been told before.

The archive tape you heard from the 1973 rally in Washington Square Park is from footage shot by the Lesbians Organized for Video Experience Collective, or LOVE. If you’re interested in donating to or using the LOVE collective tapes, please contact Tracy Fitz, that’s Tracy with a “y,” tracy@innerbeing.net, or the Lesbian Herstory Archives.

A big thank-you to the folks who make this podcast happen each week: producer Sara Burningham; mentor, friend, and co-producer Jenna Weiss-Berman; audio engineer Casey Holford; our website designer Jonathan Dozier-Ezell; and social media consultant Will Coley. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

———

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Season two of this podcast is made possible with support from the Ford Foundation, which is on the front lines of social change worldwide.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher, NPR One, and wherever you get your podcasts.

So long. Until next time.

###