Shirley Willer

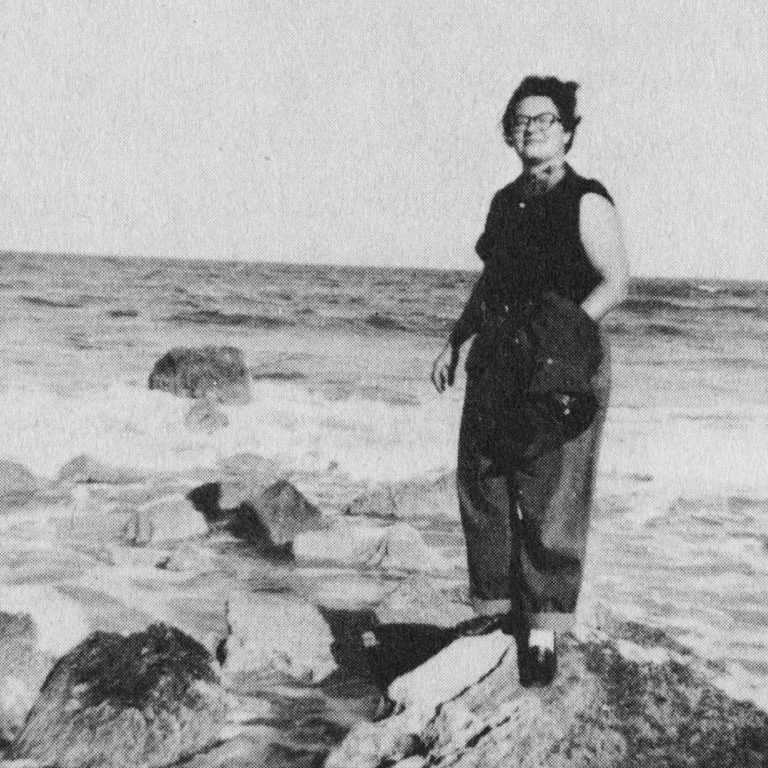

Shirley Willer in the mid-1960s at the beach in Atlantic City, where she and her partner, Marion Glass, had gone to scout a location for a Daughters of Bilitis outing. Credit: © Lesbian Herstory Archives

Shirley Willer in the mid-1960s at the beach in Atlantic City, where she and her partner, Marion Glass, had gone to scout a location for a Daughters of Bilitis outing. Credit: © Lesbian Herstory ArchivesHelp Us Find “Pennsylvania”!

Shirley Willer traveled the country in the 1960s, spreading the word about the homophile movement, and sharing information about both the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society. Her work was financed by a wealthy lesbian who chose to remain anonymous. The donor went by the codename “Pennsylvania.” Do you know who she was? Please help us find her! If you have any information, write to us at hello@makinggayhistory.com.

———

Episode Notes

What do you do when you’ve been slapped around by a policeman simply because the way you look and the way you’re dressed leads him to believe you’re a lesbian? Or when your friend—your gay brother—is left to die in a hospital because he’s a “flaming queen”? Shirley Willer got angry. And, to put it the way Frank Kameny might (and did, in this MGH episode), Shirley was also radicalized and decided that she had to “do something” because, as she says in the 1990 interview featured in this episode, “it had to stop.”

For someone who wanted to do something to make the world a better place for gay people in the 1940s (which is when Shirley got hit by a policeman and her friend was left to die) there were virtually no options. But by 1962, when Shirley moved to New York City, the nascent LGBTQ civil rights movement (then called the homophile movement) gave her the outlet she’d been searching for—first as president of the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis and then as national president.

But the Daughters of Bilitis proved to be an all-too-tight fit for Shirley, whose instincts for activism were more closely aligned with Frank Kameny and the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., rather than the more low-key and cautious Daughters of Bilitis. The conflicts came to a head in 1968 at a meeting of the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations (NACHO) and soon after, Shirley quit the movement. As she told Eric Marcus, “I felt that I had really failed. I saw no future for DOB. For me this was like my religion. To have it explode in your face was not a successful ending to a career.”

———

Watch a July 11, 1987 interview with Shirley Willer from the Lesbian Herstory Archives Daughters of Bilitis Video Project.

Shirley Willer’s oral history can be found in Eric Marcus’s book Making Gay History.

In this episode, Shirley talks about a late 1940s meeting with Pearl Hart, a Chicago attorney, regarding the formation of an organization for gay people. Pearl Hart has an extraordinary story of her own, which you can read up on here and in an April 7, 2014 birthday profile in the Box Turtle Bulletin.

Shirley also mentions The Well of Loneliness, a 1928 lesbian novel by the British author Radclyffe Hall, which many of the women interviewed for Making Gay History cited as being influential in their understanding of themselves. A 2005 article in The Guardian provides interesting background on the book and why it wasn’t published in Britain until 1949.

To learn more about the Daughters of Bilitis and Shirley’s involvement with the pioneering organization, read Marcia M. Gallo’s Different Daughters—A History of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Rise of the Lesbian Movement. Seal Press, 2007.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

Today you’re going to meet Shirley Willer. Shirley was born in Chicago on September 26, 1922.

I had read about Shirley in a gay history book—about how she celebrated her 40th birthday by moving to New York and joining the Daughters of Bilitis, an organization for lesbians founded in 1955. And how she became president of the local chapter, then national president.

But that’s not the story she’s going to tell you today. We’re going farther back, to her life in 1940s Chicago and what drove her to become the passionate activist I’d read about.

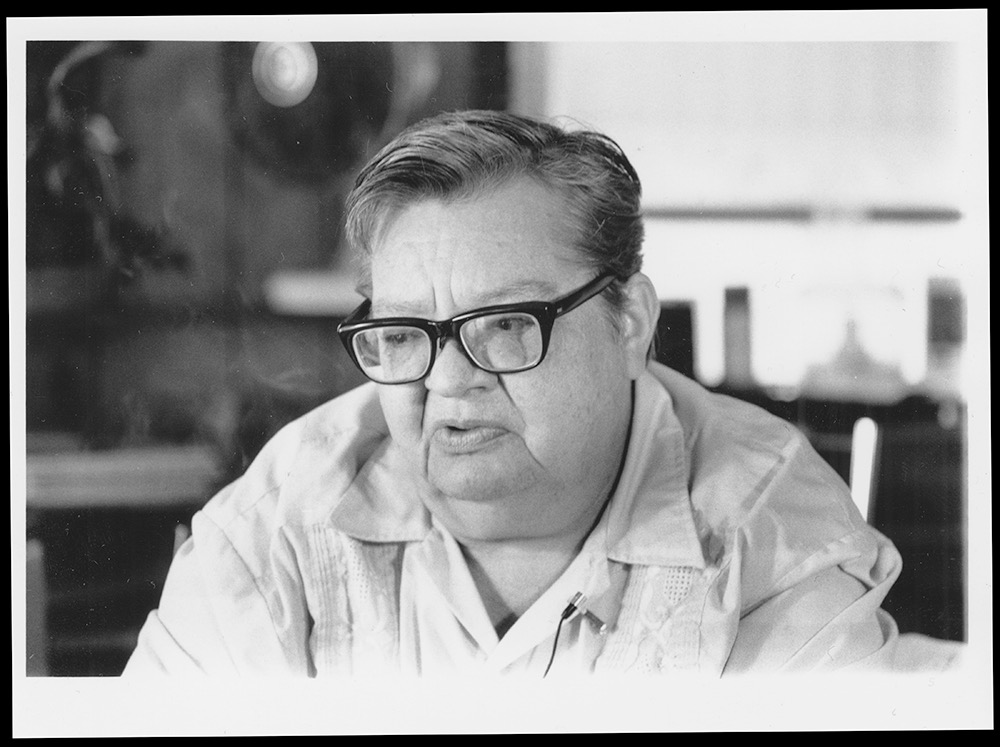

So here’s the scene. I arrive on the doorstep of Shirley’s one-story house in a working class neighborhood of Key West, Florida. It’s a warm, humid fall day in the low 80s. A young woman in cutoff shorts and a tank top answers the door and leads me through a dark hallway to a sunroom at the back of the house. I get a glimpse of Shirley over the young woman’s shoulder.

Shirley is big. She’s sitting in a wheelchair a size too small. Her hair is mostly gray and cut in a flat top style. She looks out from behind thick Coke-bottle glasses, and gives me the once over. I notice that I’m also being inspected by the birds she keeps on her sun porch. Shirley sets her cigarette in an ashtray that’s piled high with butts, and reaches out to shake my hand. I unpack my equipment and clip the microphone to her blouse. I press record.

———

Shirley Willer: I may have to remove this little guy or he’s gonna be taking over the mic. Get over here. You don’t want to, I know.

I’m a nurse, and I discovered I was gay—we’ll use the word, it’s easier nowadays—sitting in a classroom listening to a lecture on mental hygiene.

Eric Marcus: What was the lecture? What did she say in the lecture?

SW: She described what a lesbian was like. I said, “Oh, gee, I’m one of those things!”

EM: What was her description?

SW: Um, how you were not attracted to men. How you had these violent crushes on women.

EM: Where in 1941 would you have read about such things or heard about such things?

SW: Well, I know there were copies of The Well of Loneliness around. Because after I… When I found out I went home and told my mother. And she was able to get a hold of a copy of the book. Then I started looking up words in the dictionary and then the encyclopedia.

EM: And what did you find?

SW: Not very pleasant descriptions. Pervert. It was a perversion of the natural instincts of the human animal. And at that time it was considered a criminal act. In fact, I remember being picked up by the front of my shirt and slapped back and forth by a policeman because I was on the streets at 11 o’clock and I had on slacks, women’s slacks and a sport shirt.

EM: A policeman?

SW: Policeman. I was walking down Rush Street trying to find a gay bar that I’d heard of. I had a woman’s shirt on and women’s slacks, but obviously made as tailored as possible.

EM: Tailored clothing means what?

SW: A Brooks Brothers suit. Now, I’m not talking about a man’s suit. I’m talking about a woman’s suit. I had massive muscles here and they had to rebuild the top here. Oh, that cost a fortune. I think it cost me all of $120 to have it tailored.

EM: Did the policeman say anything when he was hitting you to indicate…?

SW: He called me names. “God damned pervert. You queer. You SOB,” and so forth.

EM: And you couldn’t call the police, could you?

SW: No, I couldn’t call the police. It was a policeman! But, in fact, I finally did find the bar. I’m not sure, but it might still be there. It was the Seven Seas.

EM: Was this the first bar you went to?

SW: Yes.

EM: So you got slapped around the first time you were on your way to a bar?

SW: The first time I was on my way to a bar.

EM: Stupid question here. Was that frightening?

SW: I wasn’t frightened, I was angry.

EM: Why were you angry?

SW: He had no right to do that to me. And that’s been my attitude all of my life. They have no right.

EM: How did you even find the bars? How did you know about these things?

SW: Well, you see, I started out as most people do, thinking I was the only one. Then I realized there had to be more out there or there wouldn’t be any kind of books. And there wouldn’t be any definitions. But of course I didn’t know how to find them.

When the war ended, all these corpsmen came back.

EM: These are the male nurses who came back.

SW: They were corpsmen in the Navy and in the Army. And then, of course, when they were working in the hospital, we met each other. And most of ’em were pretty flaming queens.

EM: When you say these guys were flaming, um, can you describe for me what that means?

SW: Today they would call it being extremely swish. They, um, the mannerisms were very limp-wristed. Even at work, they would emphasize feminine characteristics. Thank goodness the hospital was, simply didn’t seem to pay much attention to it. They did their job right, they did their job right, that’s all that mattered.

At that time, the big events in Chicago were the Halloween balls. Aragon and Trianon. They were huge ballrooms. One on the north side and one on the south side. And every Halloween all bars were off and everybody went in costume. And all of us would get tuxedos and…

EM: All the women…

SW: All the women. And dress in our butchiest styles and we’d all go to the balls. The Aragon was on the north side. The Trianon was on the south side.

These two particular big events were, again, run by the Mafia. And we’d hire limousines, you see, and get a police escort through the crowds in order to get inside and, uh…

EM: This was the one time of year that gay people could be gay.

SW: One time of year that gay people could be gay. But it was the only visible sign that there literally were thousands and thousands of gay people in the city.

EM: When was the first time you went to this, in the 1940s?

SW: It was shortly after the fellas got out of the service, because I remember they dressed me.

EM: How did they dress you?

SW: In a tuxedo. And tied my tie. And put makeup on me. I’d never worn makeup in my life! All the fellas wore dresses.

EM: When did you become aware that there was any kind of organized…?

SW: There wasn’t much of an organized movement. The only organized group that I could find out about was ONE, which was more a literary thing.

EM: And this is already by early 1950s.

SW: That’s right.

EM: So what happened during the 1940s?

SW: Before then it was pretty much on our own volition that we would… There were so many young women that were being thrown out of their homes, so we started our own little informal groups. And we would take in all the kids that got kicked out in the street. And we would keep pushing them to stop trying to hide it, um, be themselves. I believed that you should stand up and be counted.

EM: Wasn’t that dangerous for most people?

SW: It’s always dangerous for anyone who doesn’t have any money in the bank.

EM: But weren’t many of them in danger of losing their jobs?

SW: It would depend on the job they would take. Now, a majority of them wouldn’t take jobs where they were endangered. They would go for the dirty jobs, the rough jobs. Running an elevator. I remember one in particular, a very bright girl. But the only job she could get was running an elevator ’cause she wouldn’t wear a dress. So we didn’t call ourselves any particular group.

EM: How did you come in contact with Pearl Hart? And Pearl Hart was an attorney?

SW: That’s right. Talking to some of the men is where we first heard of her. There was this group of about six of us, six women. And we wanted to form some kind of an organization. So we went to see her. And we asked her, you know, how do you go about doing such a thing? She said, “You don’t.”

EM: Why did she say, “You don’t”?

SW: Pearl at that time was like everyone else. She felt that people would get farther by simply doing things quietly without announcing themselves, without having large formal meetings and so forth. Um, she was a grand old lady.

EM: Was she herself a lesbian?

SW: Ah, yes. Again, I never slept with her so I can’t swear to it.

EM: Right.

SW: But she also wore Brooks Brothers suits, except that hers were tweedy.

EM: So that was one of the indicators.

SW: That’s right. It was a very sad time to be alive.

EM: Why is that? Why do you say that?

SW: Well, for example, we had one young man who was studying medicine. He was working as a nurse. He worked the 11:00 to 7:00 shift.

EM: 11:00…

SW: Midnight until 7:00 in the morning. Then at 9 o’clock he would have his first class. And, uh, so he would go home and he’d shower and a friend of his would pick him up and they’d go to class together. Well, he fell asleep while he was waiting one day and by the time his friend got there the couch was totally in flames.

EM: He’d been smoking.

SW: Yes, and he was very, very badly burnt. They took him to a Catholic hospital run by a brotherhood. He did not receive good care…

EM: Because…

SW: Because he was queer. Now I couldn’t go and see him because women weren’t allowed to go into the hospital whatsoever, but the men did. But they weren’t even changing his dressings. And even then we knew enough to use salt water dressings. If you can’t do anything else, you put dressings on and keep them saturated in salt water to keep them wet. They weren’t even doing that. They’d just let them dry and then seepage was coming through and…

So we moved heaven and earth to try and get him transferred out of there to a veterans’ hospital. And we got him moved the day before he died.

EM: That must have made you furious.

SW: That’s right. In fact, I’ve spent a large percent of my life being angry.

Barney, his name was. Barney.

EM: I guess that shocks me. It didn’t occur to me that such a thing happened before AIDS.

SW: Oh, yes. The hatred of the gay has existed as long as we’ve existed.

EM: But not to care for somebody who’s sick.

SW: That’s right.

EM: Didn’t that go against everything you were ever taught?

SW: Right. And of all people, those who pretended to be religious… I can’t say any more.

EM: Tape one, side two.

Uh, this upsets you a lot.

SW: Uh, huh.

EM: Still.

SW: Always will.

EM: How many years ago was this?

SW: This was about ’47.

EM: That’s more than 40 years ago.

SW: That’s right.

EM: Why is it…? What… What is it about that experience that was… that was and is still so upsetting?

SW: The…

EM: Here you go… a tissue.

SW: I think anybody who calls themselves an American, who believes in any kind of religion, to deliberately allow someone to die or force them into a position where they’re going to die, it’s unforgivable.

EM: So they killed Barney.

SW: They killed Barney. Because he was gay. He was another one of “those.” It was as though they did it to a brother or a sister or a close relative. He was a close relative.

EM: He was somebody you loved.

SW: He was one of my brothers.

EM: Was he a young man?

SW: I would say he was about 24.

EM: He was a baby.

SW: Yes.

EM: They killed a kid.

SW: Yeah.

EM: That’s incredible.

SW: I think this probably had a great deal to do with my aggressiveness. I had done it very privately prior to that time, you know, trying to set something up where we could have an ongoing group that would meet and have meetings and try to accomplish something. I had no specific goals in mind then. But after Barney’s death, I think, many of us became much more aggressive. We had to stand up and be counted. We had to make an impression somehow.

EM: Why?

SW: You couldn’t let that go on. That had to stop.

———

EM Narration: From the turning point of Barney’s death in 1947, fast-forward to the 1960s. By then Shirley’s work with the Daughters of Bilitis was taking her on the road from Boston to Texas and a dozen places in between. She was a lesbian Johnny Appleseed, starting new chapters of the Daughters and a few chapters of the Mattachine Society wherever she went.

When I asked Shirley who financed her travels, she explained that she had a wealthy benefactor, a gay woman, who secretly donated more than a hundred thousand dollars to the fledgling movement. That’s the equivalent of $750,000 dollars today. Shirley was her conduit. If anyone knows who that person was, please email us at hello@makinggayhistory.com. The benefactor was also known as “Pennsylvania.”

Shirley Willer died on December 31, 1991 from heart failure. She was 69.

To learn more about Shirley Willer go to makinggayhistory.com. That’s also where you can find out about attorney Pearl Hart and her pioneering work defending oppressed minority groups in the early 20th century. And you can listen to all our previous episodes there.

———

Making Gay History is very much a team effort, so I’ve got a few people to thank, starting with our executive producer, Sara Burningham. Thank you also to our co-producer and guardian angel Jenna Weiss-Berman. Thanks also to our audio engineer Casey Holford, our webmaster Jonathan Dozier-Ezell, and our social media strategist Will Coley.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Season two of this podcast is made possible with support from the Ford Foundation, which is on the front lines of social change worldwide.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts.

So long. Until next time.

###