Chuck Rowland

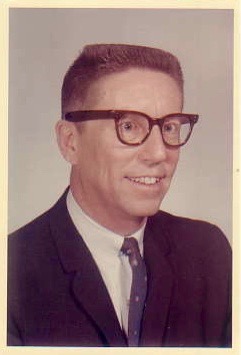

Chuck Rowland in the early or mid-1960s, when he was a high school teacher in Orange City, Iowa. Credit: From the estate of John Callahan. Used by permission.

Chuck Rowland in the early or mid-1960s, when he was a high school teacher in Orange City, Iowa. Credit: From the estate of John Callahan. Used by permission.Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: Like many World War II veterans, Chuck Rowland returned to civilian life full of hope and optimism for the future. For Chuck, these weren’t just thoughts. He set out to change the world by going to work for the American Veterans Committee (AVC), a left-liberal organization for veterans that, among other radical concepts, promoted racial equality and equal rights for women. He also joined the Communist Party during that period of his life believing that the communists “were out there on the barricades or picketing or closing down something—doing something about [socialized medicine, integration, and the rights of women] instead of just talking.”

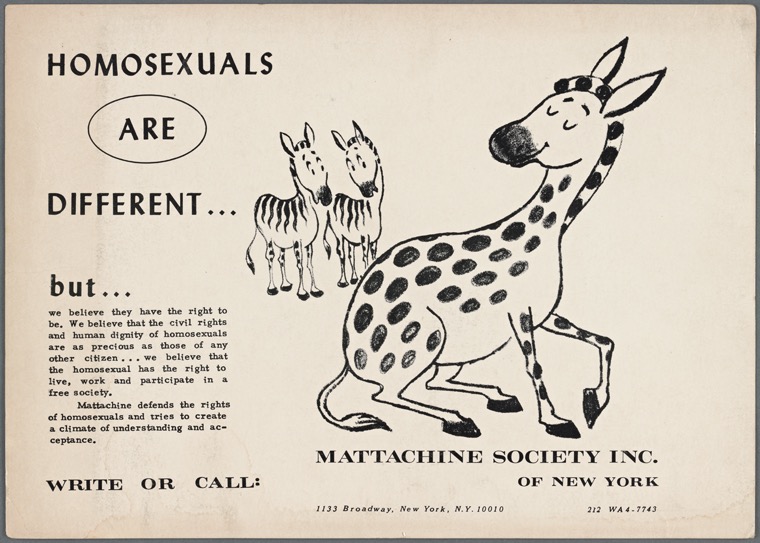

In 1950, Chuck brought all of his organizing and social theory experience to a new challenge. Having left behind the AVC and his membership in the Communist Party, Chuck joined with four other gay men in Los Angeles to launch the Mattachine Society, the first gay rights group to take root and grow in the U.S., first along the West Coast and then across the country. But just three years later, Chuck and the other Mattachine founders were out and Chuck struggled to find a way forward. His lasting legacy is a civil rights movement that changed the course of history and an LGBTQ theater company that he founded in Los Angeles.

To learn more about Chuck Rowland and the Mattachine Society, we encourage you to explore the resources that follow below.

———

For more information on Chuck Rowland, you can find a brief biography here.

You’ll find a more detailed overview of Chuck’s life and information about the early history of the Mattachine Society and Chuck’s involvement with ONE, Inc. here.

Chuck Rowland’s oral history can be found in Eric Marcus’s book Making Gay History.

For an in-depth look at the Mattachine Society and Hal Call, who was behind the coup that removed the organization’s founders, including Chuck Rowland, have a look at James T. Sears’s Behind the Mask of the Mattachine: The Hal Call Chronicles and the Early Movement for Homosexual Emancipation.

We also recommend Pre-Gay L.A.: A Social History of the Movement for Homosexual Rights by C. Todd White. This book covers Chuck Rowland’s involvement with both the Mattachine Society and ONE, Inc.

In 1982, Chuck Rowland founded the Celebration Theatre in Los Angeles, California, an award-winning theater company that’s dedicated to telling the stories of the LGBTQ community and is in operation to this day.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

In this episode you’ll meet Chuck Rowland. Chuck was one of five men who gathered in a Los Angeles apartment on November 11, 1950, to found the Mattachine Society—a gay rights organization.

Mattachine wasn’t the first gay rights group in the U.S. There was a very short-lived organization called the Society for Human Rights, which was founded in Chicago in 1924. But the Mattachine Society lasted, and very quickly chapters spread along the West Coast and across the country.

Just a quick fun fact about one of the other five guys. In the early days of Mattachine he went by the initial “R.” Most people who had anything to do with the gay rights movement back then used pseudonyms. His real name was Rudi Gernreich. He was an Austrian-Jewish refugee and in the 1960s he became famous for designing the topless bathing suit, better known as the monokini. Just Google it, but not at work.

So back to Chuck Rowland. Chuck served in the Army during World War II and came home full of idealism and determined to change the world. He went right to work for a veterans organization that promoted racial equality and women’s rights, setting up new chapters across the entire Midwest.

Then he joined the Communist Party, because he thought that the communists knew how to get things done. But it was fighting for the rights of gay people that really captured Chuck’s passion.

To Chuck it didn’t matter how bad things were for gay people in the early 1950s. Like a lot of the early gay and lesbian activists I met, Chuck had an internal compass that told him he was right and the rest of the world was wrong. I wish I’d had that compass when I was a young man.

Chuck had a vision for a national civil rights movement and wasn’t gonna let the police, the government, or the church get in the way. What he hadn’t counted on were the gay people who would get in his way.

I met Chuck at his small one-bedroom apartment where he lived in Hollywood, California, just down the block from Grauman’s Chinese Theater. He was two days shy of his 72nd birthday, but seemed so much younger. I think it was just his energy more than anything.

As I step in Chuck’s front hall, I notice a portrait of Dr. Evelyn Hooker hanging on the wall. That’s the psychologist who did the first study comparing gay men to straight men. You can hear her story in an earlier episode.

She proved that gay people were no crazier than straight people. Chuck explains that he was one of the 30 gay men in Dr. Hooker’s study. I’d just met Dr. Hooker two days before, when I interviewed her in Santa Monica. I had no idea that they knew each other, but I should have guessed because Dr. Hooker told me that she’d been a guest speaker at Mattachine meetings.

So Chuck takes a seat on his living room sofa. I sit across from him in an easy chair and set my tape recorder on his glass coffee table. I clip the mic to his blue button down shirt and press record.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Chuck Rowland, Tuesday, August 22, 1989. Location is Los Angeles, California. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Chuck Rowland: Unlike so many people, I know so many people who had guilt feelings. I never had any fuckin’ guilt feelings. I knew I was gay probably by the time I was–certainly by the time I was nine. At 10 I fell in love for the first time with this beautiful boy. Ah, this was no puppy love affair. I mean, I would have… I would have killed or died for that boy. And I knew it was the real thing without… I knew I was in love. And I knew of course that this was strange, but it was so clear to me. I knew I wasn’t crazy. That never crossed my mind. My dad was a pharmacist. And his drugstore, I grew up in the drug store. His drugstore had the only newsstand in town, a little rural village called Gary, South Dakota, and population 535 at that time. My father, being a pharmacist, was one of the leading citizens of the community. Ah…

EM: You were saying you were grateful that he had a newspaper, I’m sorry that…

CR: He had the only newsstand in town. And we got—and he didn’t want to put it out in front ’cause it was too daring—but he got copies of Sexology. I don’t know, I think that maybe it’s still in print. I don’t know.

So of course I immediately snatched a copy and took it out to the backyard of our house. So I remember this very distinctly. I was lying, I was on my stomach, in the shade, in the backyard reading Sexology.

And there was a whole special section on homosexuality. And he explained that if one were homosexual, he shouldn’t feel strange or odd or anything, there were millions of us, and that there was nothing wrong with it. Perfectly marvelous.

As soon as I read that there were millions of us, I said to myself, “Well, it’s perfectly obvious that what we have to do is organize. And we will have to…” Now I’m about nine years old at this time. “We have to organize and why don’t we identify with other minorities such as the Blacks and Jews.” And I had never known a Black, but I did know one Jew in our town. And obviously has to be an organization of other minorities and we would wield tremendous, tremendous strength.

I don’t think that there is any, any thinking gay person who hadn’t at some time back in the ’20s, back in the ’30s, has said, maybe at a bar one night when feeling a little happy, you know, “We should have an organization. We should get together and have a gay organization.” And usually you’d be laughed out of the place. People would say, “You’ll never get a bunch of faggots together. I mean, those dizzy queens, you’d never get them to do anything.”

Well, then in 1950, Bob, my best friend and former lover, was taking a course in the history of folk music that was given at the California Labor School. And for some reason Harry Hay took over the course. I don’t know what Harry’s qualifications were.

Harry showed Bob a thing that he, Harry, had written about a gay organization. And Bob brought this home and showed it to me and Dale, who was Bob’s lover at the time. And I said, “My god, I could have written this myself.” And so Bob said, “Well, you’ve got to meet Harry.” And I don’t remember it this way, but it may be right, Harry said I jumped out of my car waving the document saying, “I could have written this myself.” So Harry’s lover was Rudi Gernreich at the time. And so then Bob and Dale and Rudi and Harry and I started talking about this. And so we started having regular meetings.

EM: Now I read somewhere that at those meetings you discussed even the nature of homosexuality was and whether or not homosexuality constituted a minority group.

CR: Right.

EM: Was that new thinking that homosexuals would form a minority group?

CR: What we’d been saying is we’ll just have an organization. And I kept saying, “Well, what is our theory?” Having been a communist, you’ve got to work with a theory. I mean, “What is our basic principle that we are building on?” And this came from Harry and I give him, despite our many, many disagreements, I will give him credit forever for saying, “We are an oppressed cultural minority.” And I said, “That is it. That is exactly it.” And that is the first time that I know that the… and nobody was buying it, oppressed cultural minority. They didn’t want to be a minority. They wanted to be like everybody else. Gay people didn’t want to be an oppressed cultural minority. “Why we’re just like everybody else, except what we do in bed.”

EM: Why did you disagree with that?

CR: Because it isn’t true.

EM: Why not?

CR: I don’t think or feel like a heterosexual. My life was not like a heterosexual. I had experiences, emotional experiences, that I could not have had as a heterosexual. I think, my whole person, my whole being, my whole character, my whole life differed, differs from heterosexuals, not by what I do in bed, because I don’t do any of that in bed anymore. And I never was as sexually active as an awful lot of people. I mean I…

EM: So sex was a part of who you were, but…

CR: Yeah, but I… I believe there is a gay sensibility. I would say, “Well, there is a gay culture.” People would say, “Gay culture? What do you mean? Do you actually think that we’re more cultured than anybody else?” No, I’m using culture in the sociological sense, a body of language, feelings, experiences, thinking, feeling that we share in common.

EM: People didn’t buy what you said.

CR: They were horrified. At the constitutional convention of the Mattachine…

EM: In April ’53…

CR: … Society I made a speech. And I don’t remember what I said exactly. I was building up to a resounding climax, what I thought would be a resounding climax. And I said, “The time will come when we will march arm in arm, 10 abreast down Hollywood Boulevard proclaiming our pride in our homosexuality.” Well, I got some applause, but people were more in shock. But it seemed to me perfectly reasonable and it still seems perfectly reasonable.

EM: What did they find shocking about your comment at that time?

CR: Well, in the first place, the only way we’re ever going to get along is by being nice, quiet, polite little, uh, little boys that our maiden aunts would approve of. And this is the only way that we’re going to get along in the world. We’re not going to get along in the world by going out and flaunting our homosexuality. We mustn’t, must keep it very, very quiet. And there are people of good will, uh, who will, who will help us, but we cannot do anything naughty like having picket signs or parades. Why, only communists would do things like that.

And so they started calling us communists, we, the founders of the Mattachine. And although some of us had been and others had been fellow travelers, they began calling us communists, not because they had even the faintest shred of evidence for this accusation, but just because we were saying such daring things. I mean, that’s what communists do. They create waves. They make scenes. They make people un—unpleasant. They don’t balance their coffee cups on their knees politely.

EM: You retired from Mattachine essentially in ’53 then.

CR: Well, we…

EM: You stepped aside, anyway.

CR: See, it was growing so fast that it became obvious to me there was no way we could control it. So I said that the only thing to do is to open it to a democratic, fully democratic organization. And to this end, I proposed that we call a constitutional convention.

So I wrote a constitution, which I think was a damn good one. Never occurred to us that anybody would come up with another constitution, would arrive with another constitution. Or if they did, that they could get anybody to vote for it because we thought ours was so good. So, but they came up with this half-baked piece of shit and it was obvious that they were going to pass it.

And I said, “Well, we can’t live with this constitution. It is clearly unworkable.” And so we had a very, very quick meeting and we agreed that it was impossible. So we decided that we would resign. Then several of us tried to work… We said, “Well, we’ll try to work with some of the individual clubs.” And so I was with one club. Then for the second convention… They couldn’t solve anything at the first convention.

EM: That was the April convention…

CR: So they were going to have another convention. And I was chosen as delegate. They wouldn’t seat me. I said, “How can you not seat me?” I am sent here as a representative of my club.” And, uh, “No, because we don’t seat communists.” You know, ridiculous.

We founders of the Mattachine had given so much of ourselves, had dedicated ourselves so utterly to this. This was our lives. And suddenly it was gone, simply gone. And as a result, lovers began breaking up. People who had been the closest of friends were at, were screaming and swearing at each other.

As I think of it, in retrospect, it was a terrible, terrible time. And I felt… The time… I became absolutely suicidal because it was… This was my life. I was, was prepared quite literally to devote my life to the Mattachine, and here this, this bright glory was, was all gone. It turned to shit.

———

EM Narration: After Chuck was kicked out of the Mattachine Society, he struggled for years with alcohol and depression. In 1962 his ex-boyfriend Bob Hull, who co-founded Mattachine, killed himself. That’s when Chuck decided it was time to start over.

So he moved to Iowa and somehow landed a job as a high school teacher. At the same time, he got his master’s degree in theater and later chaired the theater arts department at a junior college in Virginia, Minnesota.

Chuck retired in 1982, moved back to L.A., and founded the Celebration Theatre. It’s still in business and its mission hasn’t changed—creating an outlet for LGBTQ voices.

When I interviewed Chuck, he told me that he’d been treated for prostate cancer. I had no idea how serious it was. And I don’t think he did either. He died 16 months later. He was 73.

———

I’ve got a few key people I’d like to thank for making this podcast possible. Thank you to our executive producer, Sara Burningham; our audio engineer Casey Holford; and our composer, Fritz Myers. Thank you also to our social media guru, Hannah Moch; our webmaster, Jonathan Dozier-Ezell; and our head of research, Zachary Seltzer. We had production help from Jenna Weiss-Berman, who believed in this project before it was even a podcast.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Funding is provided by the Arcus Foundation, which is dedicated to the idea that people can live in harmony with one another and the natural world. Learn more about Arcus and its partners at arcusfoundation.org.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also find all our episodes on our website at makinggayhistory.com. That’s where you’ll also find photos and really interesting background information on each of the people we feature. You’ve gotta see Chuck’s photo, by the way, because he looks more like Leave It to Beaver boy scout than former communist, whatever a former communist is supposed to look like.

So long. Until next time.

###