Barbara Gittings & Kay Lahusen — Part 1

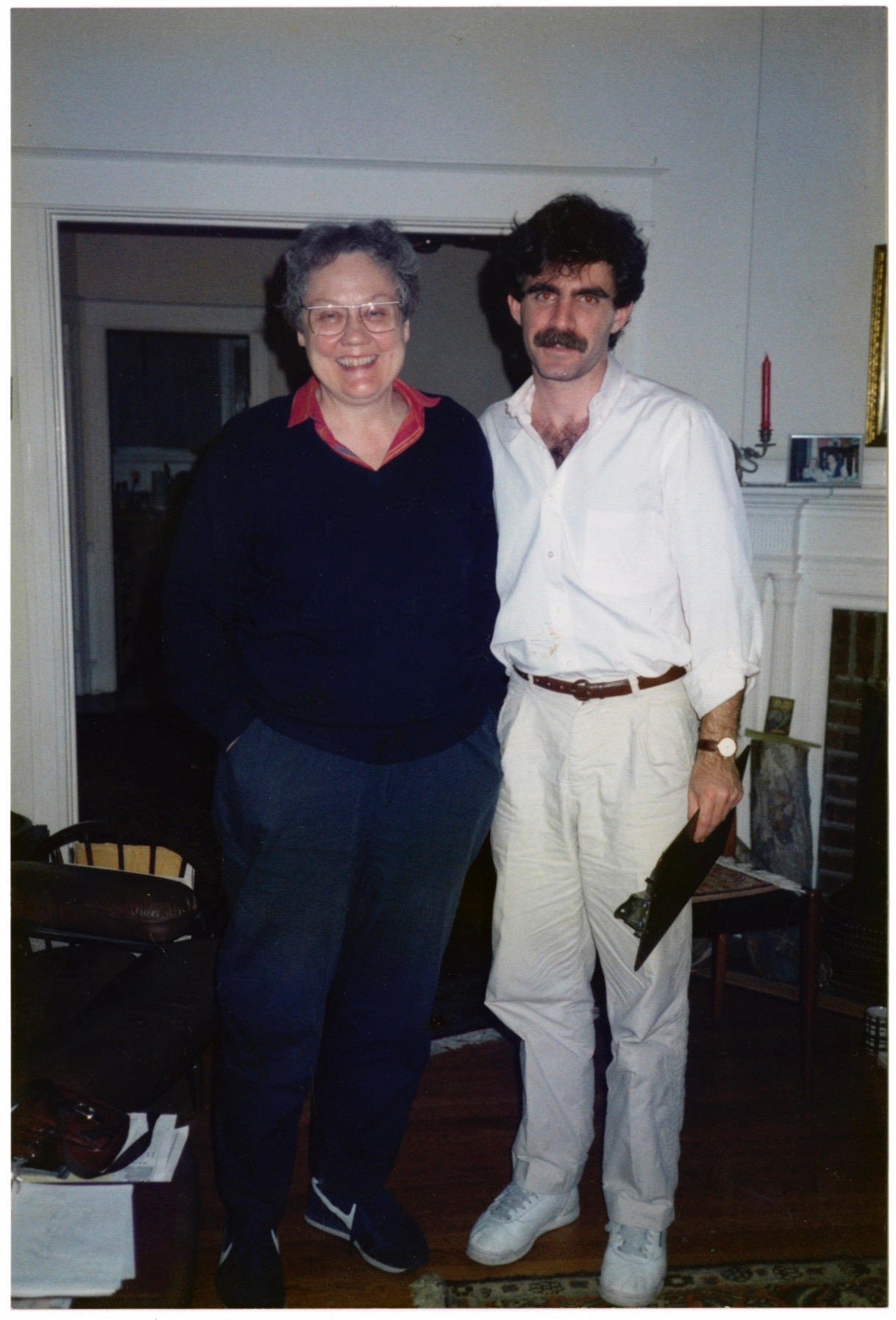

Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen at a party in the mid-1970s. Credit: Harry R. Eberlin, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen at a party in the mid-1970s. Credit: Harry R. Eberlin, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: Self-described gay rights “fanatics” and life partners Barbara Gittings and Kay “Tobin” Lahusen helped supercharge the nascent movement in the 1960s and brought their creativity, passion, determination, and good humor to the gay liberation 1970s, leaving behind an inspiring legacy of dramatic change.

Given the era in which they grew up—Barbara was born in 1932 and Kay in 1930—Barbara and Kay faced the challenge of gaining an understanding of themselves at a time when learning about homosexuality was a risky treasure hunt. Both found themselves in books—Barbara through novels like The Well of Loneliness and nonfiction books, including Donald Webster Cory’s 1951 The Homosexual in America: A Subjective Approach.

Kay did her research at the Christian Science Monitor reference library where she worked—and where material about homosexuality was shelved under “vice.” Kay recalled in her 1989 interview with Eric Marcus, “It said, ‘See Vice,’ when you went to homosexuality, which got me! I used to argue with some of the other staff about that. Of course, not saying I was gay, but arguing purely as an intellectual exercise.”

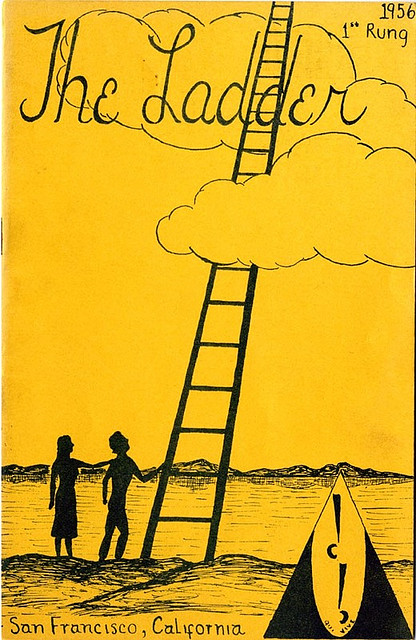

Barbara and Kay’s early involvement in what was then called the “homophile” movement was focused on the Daughters of Bilitis and the organization’s magazine, The Ladder.

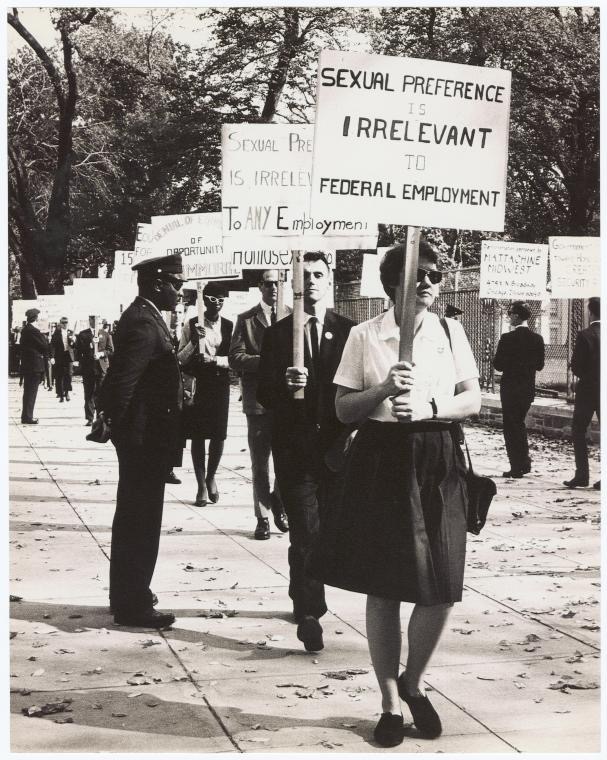

By the mid-1960s they had joined forces with Frank Kameny (who was featured in this MGH episode) to lead early public demonstrations in Washington and Philadelphia. They were among the relatively few activists from the pre-Stonewall homophile movement to make the transition into the post-Stonewall gay liberation era, each pursuing her own interests—Kay with the Gay Activists Alliance and as a photographer and author, Barbara with the American Library Association and the American Psychiatric Association.

For this first of two episodes featuring Barbara and Kay, we focused primarily on their early activism, which is why we’ve featured photographs that cover their lives and activism up until 1970. The resources that follow below are more far-ranging, although not nearly complete.

———

Kay Lahusen co-authored The Gay Crusaders, which was published in 1972, under the pen name Kay Tobin.

In 1983 Vito Russo (featured in this MGH episode) interviewed Mattachine Society founder Harry Hay and Barbara Gittings for his Our Time TV program in two parts: part one and part two.

Barbara Gittings is featured in the 1984 documentary Before Stonewall.

To see Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen in an extended 1988 interview, have a look at this three-part video available through the Lesbian Herstory Archives.

Barbara and Kay’s oral history can be found in Eric Marcus’s book Making Gay History.

Marc Robert Stein’s wide-ranging 1993 interview with Kay Lahusen is available from OutHistory.org. And here is his interview with Barbara Gittings.

For further reading, please refer to this full-length biography of Barbara Gittings by Tracy Baim, co-founder of the Windy City Times.

The New York Public Library’s Digital Collections offers nearly 1,000 photographs from the Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen Gay History Papers and Photographs collection online. For an overview of Barbara and Kay’s entire collection click on this link for the Archives & Manuscripts Division.

You can find Frank Kameny’s 2007 heartfelt eulogy for Barbara Gittings here. Kay Lahusen died on May 26, 2021; read her New York Times obituary here.

In July 2016, a historic marker dedicated to Barbara Gittings was unveiled in Philadelphia.

To learn more about the Daughters of Bilitis, we recommend exploring the resources available through the Lesbian Herstory Archives Daughters of Bilitis Video Project.

Malinda Lo wrote about The Ladder magazine in this 2005 AfterEllen article.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen were a pair of happy warriors who battled their way through decades of the LGBT civil rights movement. Over two visits in the spring and winter of 1989, I spent five hours with Barbara and Kay in their cozy living room in Philadelphia.

Barbara first found her way into the movement in mid-1950s, and Kay found Barbara in 1961. Together they devoted most of their lives to the cause.

Now, I can’t do justice to describing these two extraordinary people, so have a look at one of their early photographs on makinggayhistory.com. It’ll light up your screen.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen, Wednesday, May 17, 1989, at the home of Barbara and Kay in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Barbara Gittings: Kay. Kay.

Kay Lahusen: Yeah, what?

BG: I need some coffee.

KL: I’m making right now.

BG: And the fruit we should get out that’s on the front porch.

EM: The reason I want to ask you about… I’ll save Americans for Gay Rights for the next time.

BG: Bring some of the blue bowls. Bring out the fruit bowl from the… And there are a couple of knives I had out. Take care of your whistling… It never fails. I’m a musical person. I want a whistling kettle. I get a shrieking kettle.

EM: We have a harmonic kettle.

BG: You do! What does it do? Westminster chimes?

EM: It’s frightening. It’s off-key.

When did the two of you first meet?

BG: 1961. At a picnic in Rhode Island whose purpose was to pull together some women to try to start a Daughters of Bilitis chapter in the New England area.

EM: Do you remember what you thought the first time you saw Barbara?

KL: The first time I saw her, I thought she was a very interesting person. I was quite taken with her.

EM: And you?

BG: And I was taken with her. I happened to answer the door when she rang the bell for this picnic. And I was very taken because this was not at all what I had expected.

KL: She expected some mousy little old lady, I think, to turn up when I turned up.

BG: Because I knew that she worked for the Christian Science Monitor and my stereotypes were such that I expected this rather mousy, dour type of person, and she was everything—anything but when she turned up at the door. You know, bright, cheerful colors. Red hair. Just awfully attractive. And we started talking and jabbering away and…

EM: And this was… You were coming from where at that time? You were visiting from what city?

KL: Well, I lived in Boston.

BG: I wrote to all of the women on DOB’s mailing list who were within a hundred-mile radius of Rhode Island and invited them to start a chapter up there.

EM: That was a fortuitous invitation.

BG: Yes, very much so, brought her into my life.

KL: Well, in those days, Eric, you have to realize there were like, you know, five people who might have been possible for the Rhode Island chapter. I mean, it was nothing. It was just…

BG: I think we had all of 12 or 15 people at this picnic, and that was a big turnout. A really big turnout in those days.

KL: Was it that many?

BG: I think it was about that.

EM: What kinds of people came to that picnic?

KL: We were certainly a motley crew in those days.

EM: Married women came?

BG: Married women? Possible. Nobody stands out in my memory from that particular…

KL: Marge and her hopeless love for Jan. Jan didn’t reciprocate. And then an older woman who wasn’t with anyone, but she told Barbara to go after me, that I was a cute little package. Really ticked me off.

BG: Oh, yes. It’s been a standing joke with us ever since.

KL: Frankly, Eric, in the beginning days of the movement, I’ll tell you, the people who turned up were by and large pretty oddball.

EM: Why is that?

KL: Because in the early movement, it was such an unpopular thing to do, when most gay people were trying to blend in and pass.

EM: You were saying, you had to be a little…

BG: Yes, you had to be a little bit unconventional to be willing to come out to meetings of a group like that.

KL: And you had to have some reason to want to crusade, in spite of whatever it might cost you.

EM: And you started in what?

BG: What got me started in the movement was, I found in 1953 or so a book called The Homosexual in America: A Subjective Approach by Donald Webster Cory. His book was very much a call to arms. He was saying that we ought to be working to gain our equality and our civil rights. So I met him and found out from him that there were organizations of homosexual people.

EM: Was that a stunning revelation?

BG: Yes, yes, I didn’t realize that there were such groups.

KL: We’re using the term of the day, “homosexual.”

BG: Not “gay.” “Gay” didn’t come until the late ’60s.

EM: Was “lesbian” used at the time?

BG: Yes, but not as much.

KL: Well, it was in the statement of purpose of DOB, honey.

BG: “The variant.”

KL: Oh, the variant, that was it.

BG: The variant. They didn’t call her lesbian at all. They called her the variant. Never. Never.

KL: I forgot that.

EM: The variant.

BG: But anyway, I found out from Cory about the existence of an organization called ONE Incorporated, in Los Angeles. And lo and behold, the next vacation that I had I arranged to take a plane out to Los Angeles. And they told me about the Mattachine Society in San Francisco, so I hopped another plane and went up to San Francisco and talked to them and they told me about the Daughters of Bilitis, which had formed a year ago and was about to start a magazine.

EM: It was founded by…

BG: Eight women including Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. I did accept an invitation to come to a meeting and then I found myself in a living room in a normal social setting with 12 other lesbians, and it was a marvelous experience. And I just sat there sort of reveling in the company. It wasn’t a bar setting. These were nice women. And it made a big difference. But I didn’t actually join Daughters of Bilitis until two years later, in 1958.

EM: So ’58 you decided, what made you decide to…?

BG: I was invited by Del and Phyllis in San Francisco to help start a New York chapter. I guess they had sized me up as someone who would be willing to take the bit and run a little.

EM: How many were in the New York chapter when you started out?

BG: Official members? You might have had 10.

EM: In all of New York City.

BG: Official members, yes, but a lot more turned up for the social events, the public lectures, …

KL: Thirty, 35, if we were lucky.

BG: That was a lot.

KL: That was a lot.

BG: That was a lot for an invisible people at a time when you could hardly poke your nose out.

KL: Daughters of Bilitis didn’t have big public lectures. Mattachine did, but we members of Daughters of Bilitis would go.

BG: And sometimes we would co-sponsor, so we’d sort of hitch with Mattachine’s greater strength to get our name onto something.

KL: And it was usually a lecture on the law and changing the law.

BG: Or on changing homosexuality.

KL: Or it was some psychotherapist or some shrink.

BG: Some shrink looking for clients or to cure, usually.

KL: Or a gay therapist who wasn’t out, and who just got up and gave an academic paper on…

BG: Or there were, there were…

KL: Fritz, what did he always used to talk about? Monkeys and things. Homosexuality and animals.

BG: These lectures were really excuses…

KL: … to get together…

BG: To get together and to let people come out a little bit. The content of the lecture really didn’t matter that much. We really needed the recognition that we got from these people who were names in law and ministry and the mental health professions. They had a credential and they were willing to come and address a meeting of ours instead of ignoring us entirely. That was important.

EM: Just by coming.

BG: Just by coming and recognizing our existence and our being a legitimate audience. That gave us a boost.

KL: Most gay people in New York who had any kind of income were going to the therapist.

EM: What did the therapists tell them at this time?

KL: Usually trying to cure them.

EM: Fix them.

KL: See, I decided at 18 I was right and the world was wrong. But the people who were in New York were in that intellectual stew pot there, and the going theory at the time was that you were sick and you should go to the doctor and get turned around. Deep analysis. Find out what went wrong in your childhood and so forth. Not too many people just, you know, thought for themselves and thought, you know, this is a crock of shit.

BG: But, anyway, we would have these events, and then Daughters of Bilitis had its own socials and what were called “Gab ‘n’ Java” sessions. Literally, talk and coffee. And there was a topic for discussion that evening. Topics like telling your parents. Going to the therapist. Legal issues. Legal problems. Whatever was the going…

KL: Should lesbians wear skirts.

BG: Oh, yeah. Acceptance by the world at large.

EM: Should lesbians wear skirts?

BG: Well, that was a big thing.

KL: Gus would tell endlessly about her therapist and what her therapist said. Therapy was…

BG: Very big.

KL: … the overriding thing then. Law reform was secondary and politics…

BG: And yet, obviously I was beginning to feel my crusading oats a little bit. I couldn’t help it. And yet I didn’t have a very clear sense of what we were doing and why we were doing it. We sort of bumbled along but where we were going, if you had asked me, I probably wouldn’t have been able to say very clearly.

EM: When did you develop an awareness…

BG: Well, Kay was a big help because Kay’s got a very, very clear mind and some very definite ideas about the world, much more…

KL: The Mattachine guys pushed things along. After all, they did a sit-in in a bar and demanded to be served.

EM: This was the Sip-In. I’ve interviewed a couple of people on this event, including Dick Leitsch.

KL: And that was very important.

BG: Well, and we’re moving along. But this coincided…

KL: Randy Wicker was the first to picket.

BG: He picketed the White Hall Induction Center in 1962 or 1963. Yes.

KL: All very exciting.

BG: And this is beginning to filter through to me, that you could do this like that…

KL: But I think even before the real activism, Barbara and I were unhappy with the Daughters of Bilitis posture.

BG: It was sort of a scolding teacher attitude.

KL: It was, “Now, you lesbians had better put on a skirt and shape up and hold a job and go to work 9 a.m. to 5…”

BG: “… and make yourselves acceptable to the world…”

KL: “… and make yourselves acceptable…”

BG: “… and then you can expect something of the world in return.” It was scolding the laggard lesbian.

KL: Right.

BG: And we didn’t, somehow it didn’t really sit well with us.

KL: It was pointed toward the ne’er-do-wells who would loll around in the gay bar all day long and…

BG: … and we didn’t know any of those.

KL: As if this was…

BG: … the majority of us…

KL: … the most of us. Whereas the most of us really were in skirts fitting in all too tightly.

BG: Right. Very painfully wearing the mask.

KL: I know I did at The Monitor. I was in a skirt every day, fitting in all too tightly. We didn’t like it, and we thought it was very demeaning, and we thought it was very inappropriate.

BG: And it seemed to me that at every national convention of Daughters of Bilitis, Kay and I would come up with radical proposals that were always voted down.

KL: We didn’t want the name, we wanted the name of the magazine changed.

BG: We wanted memberships for men, we wanted associate memberships for men. We wanted to change the name of the magazine. We wanted to change the composition the national board.

KL: The magazine was called The Ladder because you were supposed to climb up the ladder…

BG: Did you ever see the cover of the first few issues?

KL: … and into the human race on an okay basis.

BG: Very badly drawn. The first six issues or so had this picture, a ladder, literally, from some kind of a muddy, muddy marshland with some vaguely humanoid figures down there and this ladder up into the clouds and into the sky.

KL: The little lesbian is beginning to climb the ladder, upgrading herself so that she will become an okay person instead of a variant who has a poor self-image, who doesn’t go to work 9 to 5, who doesn’t hold a regular job, who isn’t a participating member of society, as if there weren’t thousands of lesbians who were already…

BG: … fitting in all too well.

KL: … great contributors to society. No recognition of them.

BG: What they needed was support. Help to get the bigots off their backs and ways to meet other lesbians. They didn’t need the…

KL: … the scolding.

BG: … the teaching. They didn’t need to be taught. They really didn’t need to have to learn that much about themselves. But education of the variant was one of the big things in Daughters of Bilitis. Well, we were sort of itching under all of this, and yet we stuck with Daughters of Bilitis for several years, especially because DOB was then joining with several other gay groups in the east to form what was called ECHO—East Coast Homophile Organizations. The word “homophile” was very big in the late ’50s and the early ’60s.

KL: “Homosexual” was deemed too clinical. So they tried to conjure up this word, which still sounds clinical.

BG: “Homophile” was the word they came up with. It was also supposed to mean that you could be heterosexual and support the organization and belong to it.

KL: The theory was you could make up your own word, but it never did sail.

BG: Anyway, we met Frank Kameny at one of the ECHO conferences…

EM: This is in the early ’60s.

BG: Early ’60s. He was fantastic. He’d been discharged. He was an astronomer and physicist.

KL: Did you read my chapter on him [in The Gay Crusaders]? He is so eccentric, you’ll have to forgive a lot.

EM: I’ve met him.

KL: He’s worth it.

BG: But he was a big influence on me because he had such a clear and compelling vision of what the movement should be doing, and I just…

EM: And that was…?

BG: That was that we should be standing up and demanding our full equality and our full rights and to hell with the sickness issue. They put the label on us. They’re the ones that need to justify it. Let them do their justification. We’re not going to help them.

KL: So the burden of proof is on them. In the absence of valid evidence to the contrary, homosexuality is not a disease, impairment, blah, blah…

BG: … malfunction, disorder of any kind. It is fully on par with heterosexuality and fully the equal of it. And when he put that forward as a…

KL: … credo…

BG: Yes, a credo for the movement in 1964, it was the most radical thing that had come down the pike.

EM: And DOB said, “No, we can’t take a position on it.”

BG: DOB was one of the groups that wouldn’t go along with it.

EM: They said, “Nobody will listen to us. We have to get the professionals to say we’re okay.”

BG: We can’t say it ourselves.

KL: “So we had better help them with their research studies and all of that. And once the professionals say we’re okay, then the world will accept it.” And Frank said, “This is rubbish.” He said, “If we stand up and say, ‘We’re right,’ and nobody listens, we will not have lost anything. But if somebody listens, we will have gained something.”

BG: Even if it’s only one gay person who needs a little reinforcement.

KL: “Even if it’s only the gay people who listen, we will still have gained something.” Suddenly we’re catapulted into this vigorous intellectual back and forth where DOB was back in the mire of wanting to upgrade the variant and we were saying, “To hell with this, there’s nothing wrong with the variant, it’s society.”

BG: That’s right. That was the shift that Frank helped put into focus for us.

KL: Well, he packaged it.

BG: Yes, he did. He marketed it. That is, he really pushed for its acceptance by the ECHO affiliate organizations at these ECHO meetings.

KL: Of course this was a very uneasy alliance because DOB wasn’t ready to go along with all this stuff. For one thing, it was the intellectual East vs. San Francisco, where they have nice coffee klatches and all that, right? And Florence said…

EM: Florence Konrad…

KL: Yes. “This isn’t the kind of subject matter that can be marketed like toothpaste.” And Frank said, “Unfortunately, this can be marketed like toothpaste.” Well, poor DOB. They had never been grabbed by the short hairs and shaken up this way in their lives, these San Francisco ladies.

BG: But what happened was, we were editing The Ladder around that time.

KL: Well, Barbara was the editor.

BG: I was the nominal editor. Actually, we both worked on it.

EM: Of The Ladder…

KL: And, Eric, we would go out and would distribute it ourselves. We would go to newsstands. We had…

BG: And to bookstores. Only two places in New York would take it. We tried distributors. They wouldn’t touch it.

KL: This was a labor of love. You’ve got to realize you’re talking to two fanatics here.

BG: I mean, we spent our own gas money and our own everything to do this.

KL: We were living on a shoestring. We are like, you know, the little old lady in tennis shoes, to use a sexist phrase, “lady.” We have a little old lady in tennis shoes here, locally, who’s outside our supermarket handing out her socialist literature all the time. That’s us in the gay movement. You know what I mean? Little old ladies in tennis shoes living on a shoestring. Totally fanatics. Caught up in a cause.

BG: You’re caught up in it and there’s tremendous reward. Sure, there are setbacks, but there’s a satisfaction in seeing the accomplishment, in seeing the progress forward. For every setback, we’ve made three major strides forward.

KL: Wouldn’t have it any other way.

BG: I can’t imagine not being gay. What would life have been like? Dull? Dismal? Decrepit?

KL: Barbara likes to say she loves organizations and she would have joined the conservation cause…

BG: Oh, that’s true…

KL: … or save the wilderness or save the whales or something.

BG: Oh, sure, but the gay movement is so much more fun.

EM: Thank you both again.

BG: I’ve had such a good time.

———

EM Narration: If it sounds like Barbara and Kay’s work on The Ladder was just the warmup phase of their activism, well, that’s because it was. By 1965 they were out on the picket line at the White House and the Pentagon with Frank Kameny for some of the first public protests by gay people.

And even those historic protests were a just prelude to what Barbara and Kay did after the Stonewall uprising. But these stories will have to wait until season two of Making Gay History. That’s when we’ll share another episode with Barbara and Kay.

Barbara died on February 18, 2007. She was 74. Kay lives in an assisted living facility outside Philadelphia. She’s 86.

———

As always, thank you to our executive producer, Sara Burningham; our audio engineer, Casey Holford; our social media guru, Hannah Moch; our webmaster, Jonathan Dozier-Ezell; and our researcher, Zachary Seltzer. We had production help from Jenna Weiss-Berman and our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and One Archives Foundation.

Funding is provided by the Arcus Foundation. Learn more about Arcus and its partners at arcusfoundation.org.

Making Gay History is also made possible with support from the Ford Foundation, which is on the front lines of social change worldwide.

And if you like what you’ve heard, and we hope that you did, please subscribe to Making Gay History on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also listen to all our episodes on makinggayhistory.com.

So long. Until next time.

###