Deborah Johnson & Zandra Rolón Amato

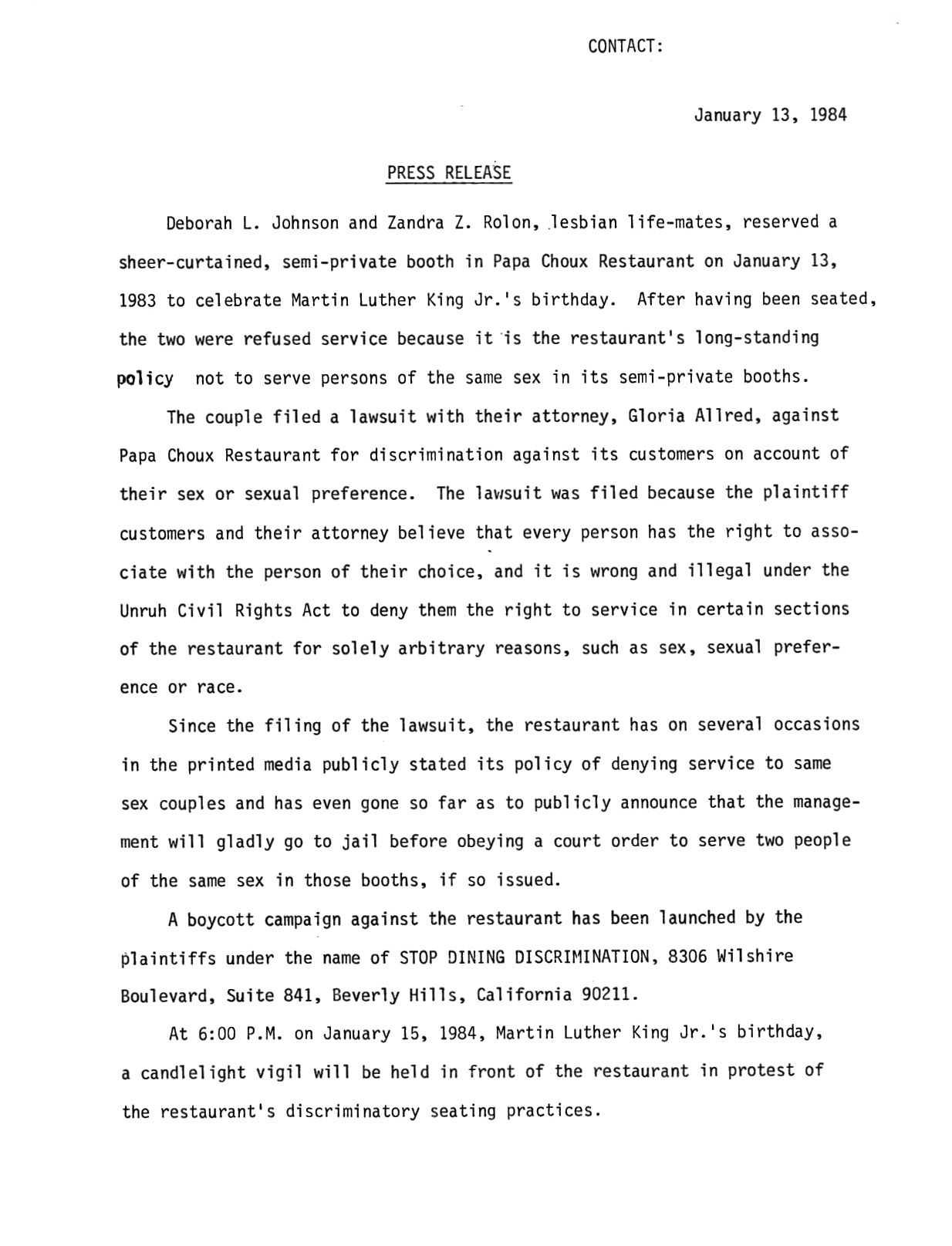

Zandra Rolón Amato (left) and Deborah Johnson in front of the Papa Choux restaurant sign following their court win in 1984. Credit: Courtesy Deborah Johnson.

Zandra Rolón Amato (left) and Deborah Johnson in front of the Papa Choux restaurant sign following their court win in 1984. Credit: Courtesy Deborah Johnson.Episode Notes

When Deborah Johnson and Zandra Rolón Amato, two 27-year-old veterans of the LGBTQ civil rights movement, headed out for a romantic dinner on Thursday, January 13, 1983, at the Papa Choux restaurant in Los Angeles, they had no idea that they’d wind up in court defending their right to be served.

Their landmark discrimination case, which was led by attorney Gloria Allred, has particular resonance today as a growing number of Americans claim they have a legal right to discriminate against LGBTQ people, most famously in the case of a baker who refused to make a wedding cake for a gay couple, which you can read about here.

To learn more about Deborah Johnson and Zandra Rolón Amato and the Papa Choux restaurant discrimination case, have a look at the links, photos, documents, and episode transcript that follow below.

———

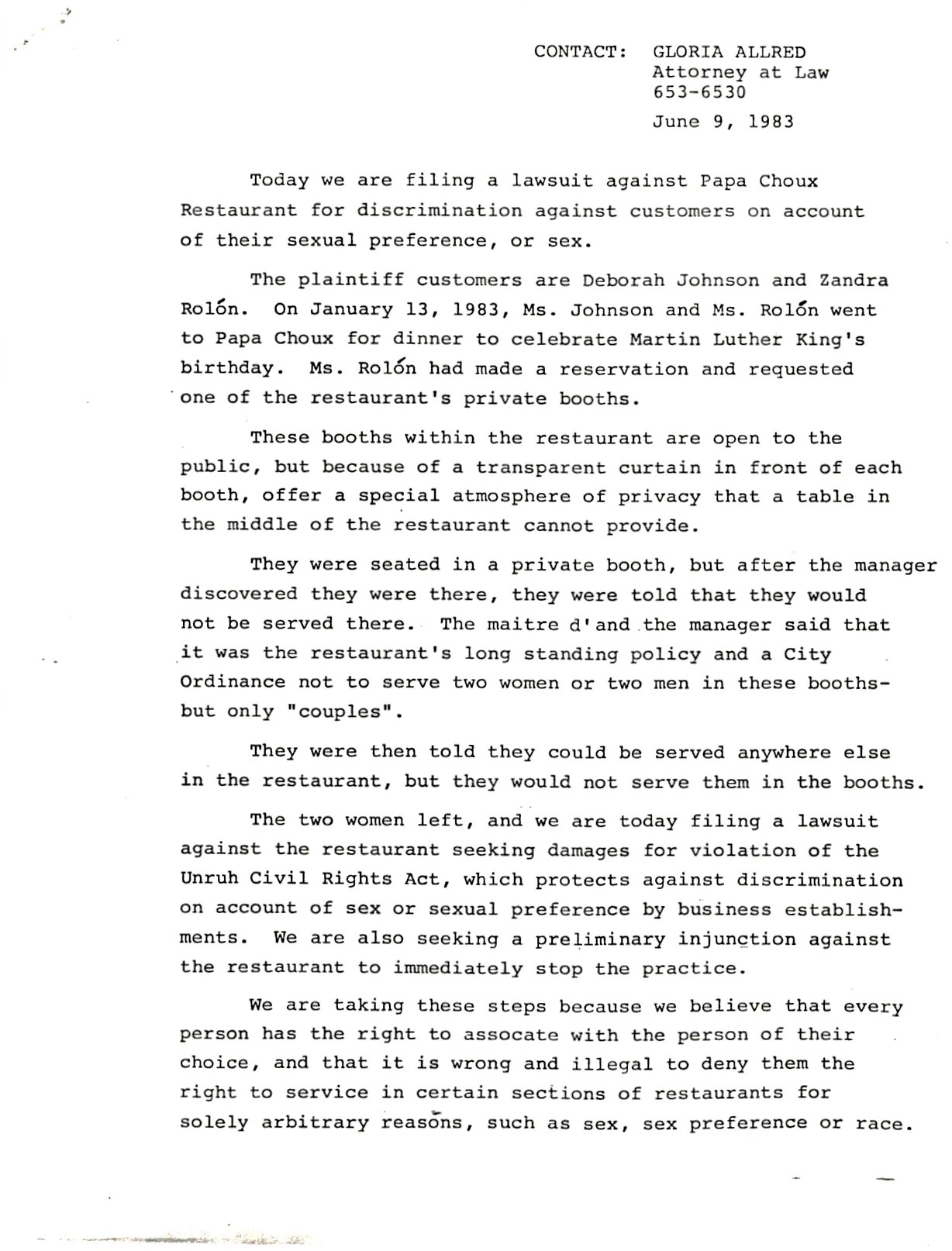

Pasted in below is the June 9, 1983 press release from Deborah and Zandra’s attorney, Gloria Allred, announcing the filing of the lawsuit against the Papa Choux restaurant.

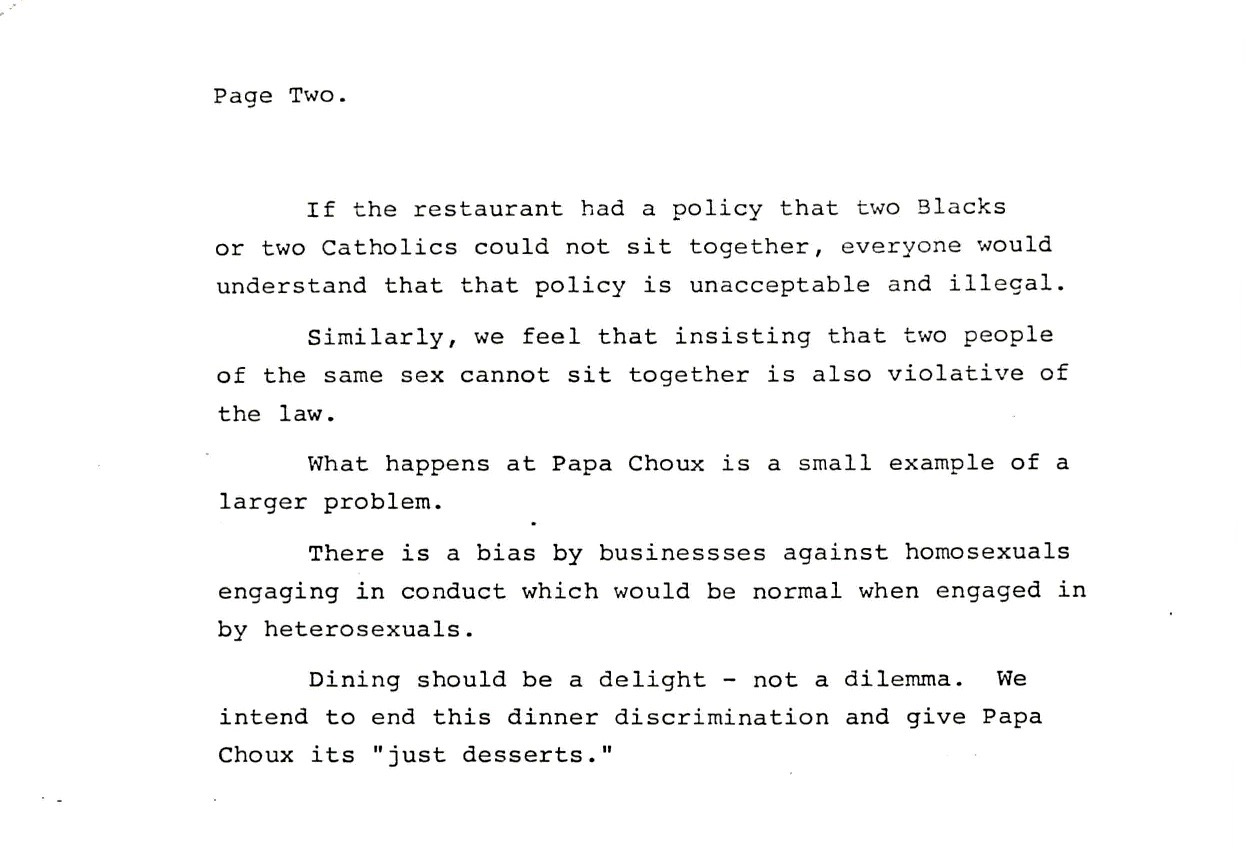

The Los Angeles Times reported on the case in an article published on June 10, 1983, which you can read below.

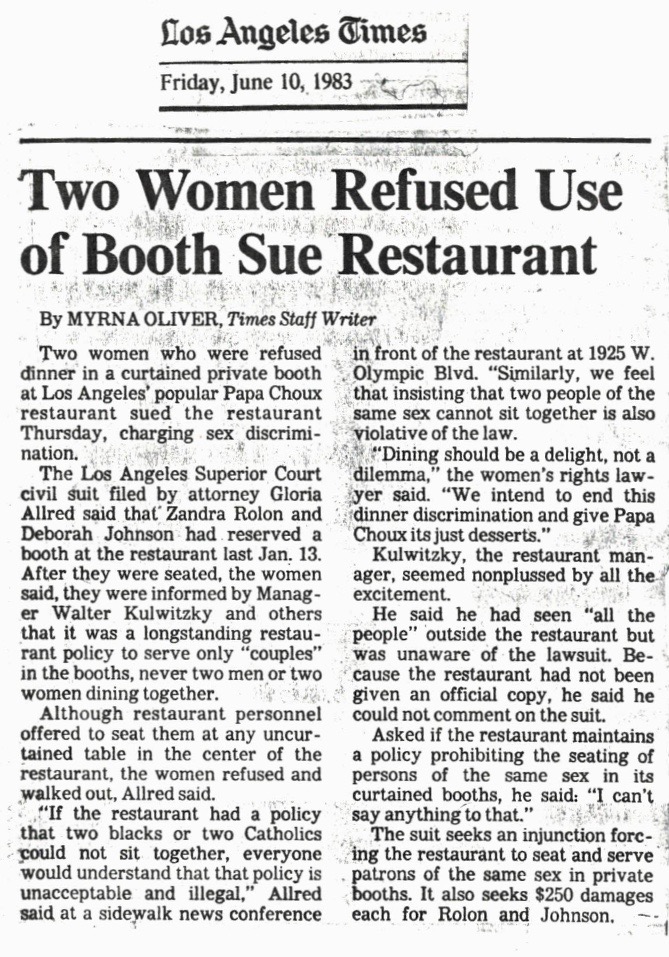

Read the January 13, 1984 press release (pasted in below) announcing a candle light vigil at the Papa Choux restaurant on on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday protesting the discrimination against Deborah and Zandra.

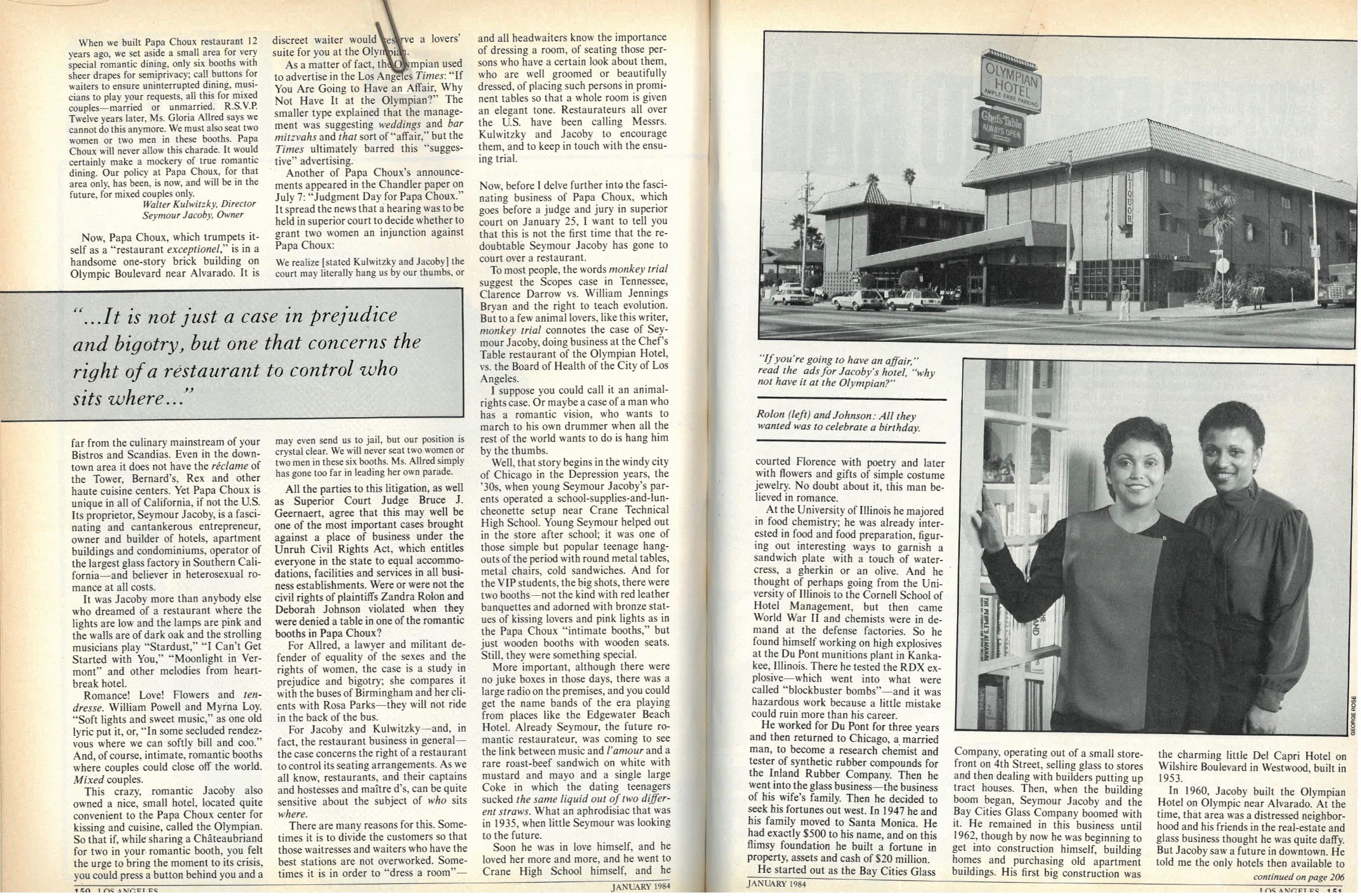

After Deborah Johnson and Zandra Rolón Amato brought their case against the Papa Choux restaurant, the restaurant’s owner placed a newspaper ad on June 24, 1983, which you can see here or below.

On May 25, 1984 the Los Angeles Times reported on a wake held by the owner of the Papa Choux restaurant to mark the “death” of “true romantic dining.” You can read the article below.

You can learn more about Gloria Allred, the attorney who represented Deborah and Zandra in their case against the Papa Choux restaurant here.

In their MGH interview, Deborah Johnson and Zandra Rolón Amato discuss their experience of being discriminated against at the Studio One gay club in Los Angeles, which closed in 1988. Here are two takes on the club: an op-ed by Ann Friedman about preserving the club’s building and a letter to the editor in which Don Kilhefner paints a portrait of a Studio One that would be familiar to Deborah and Zandra.

You can find Deborah and Zandra’s oral history in the first edition of Eric Marcus’s Making Gay History book (titled Making History).

Listen to Deborah Johnson talk about California’s Prop 8 in a 2008 interview on NPR’s Tell Me More.

To learn more about Deborah Johnson’s background and current work, click here.

And to learn more about Zandra Rolón Amato’s work, click here.

———

Episode Transcript

I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History!

In 1983, 27-year-olds Deborah Johnson and Zandra Rolón Amato went to a Los Angeles restaurant for what was supposed to be a romantic dinner. Instead they wound up in court. The two seasoned activists from the 1970s and early 1980s gay and lesbian civil rights movement found themselves face-to-face with the kind of discrimination they thought was history.

By the early 1980s, dozens of cities and counties across the country had passed laws protecting the rights of gay people in employment, housing, and public accommodations. That included restaurants. But that didn’t mean everyone complied with the laws. And a lot of those new laws had never been tested in court.

Deborah Johnson grew up in Los Angeles in what she described as a very “upper-middle-class bourgeois Black household—a very well-rooted, extremely well-connected family.” Deborah called Zandra’s family “a Mexican commune.” Zandra explained, jokingly, that she was related to three quarters of the population in Brownsville, Texas.

So here’s the scene, it’s January 5, 1991 and I’m sitting in Deborah and Zandra’s living room at their little ranch house in Aptos, California, just a couple of blocks from the Pacific Ocean in Northern California. They are on the edges of their seats, eager to tell me how they found themselves in the middle of a very public civil rights battle represented by the famous attorney Gloria Allred.

After I ask Deborah and Zandra to identify themselves, I ask Deborah what inspired her to be an outspoken and very public activist.

———

Debra: What is this book about?

Eric: I’m going to tell you, but I just want to check your voice levels. If you can just introduce yourselves.

Zandra: Zandra Rolón.

Debra: Debra Johnson

Eric: Why did you do this?

Deborah: For my life. I thought I was gonna die. I mean it was my life versus people’s attitudes. I used to secretly read the Lesbian Tide. It used to come in the brown, you know, envelope and I’d stick it in between my mattresses. And remember I used to read it and think, “God, how could they be so dykey? How could they just be playing baseball and stuff and everybody know, you know, that they’re out and how could they do this?” Because I was still very much into the double hiding thing. And then I had a sense that I was gettin’ a free ride. That there were a lot of people who were puttin’ a lot of shit out on the line, you know. Almost kind of like a stand up and be counted sort of thing.

Zandra: Whenever the occasion came up for gay people to speak on the issue of gay—on gay issues, I would always volunteer. Whether that meant on radio talk shows, on panels, colleges, the media, newspapers, anything and everything. And I think it was becoming more open about my gayness. I was also being a lot more politically involved because of the need to come out even more.

Debra: I have the advantage, one, of being educated. My experience is that there’s a lot of academic bias within the gay and lesbian movement, and if you split verbs and can’t write and all of that… And, you know, there are a lot of good grassroots activists out there who are very bright people, you know, who don’t have the college experience. And I have watched time and time again for their opinions to be devalued or them not to be taken seriously, you know particularly like when you’re dealing with people of color.

And there was just a lot racism. I mean, perhaps the most blatant kinds of racism were the exclusionary kind of policies, the sort of shit like you would see in the clubs where if you’re Black you can only get in on a certain night. We used to call it “plantation night.” Like at Studio One, you know, or that kind of thing.

Eric: They really had that?

Deborah: Oh, yeah!

Eric: Blacks were only allowed in certain nights?

Deborah: Oh, yeah, we used to picket all the time, sure. Yeah, you could only get into the club… which is sort of the irony because the gay and lesbian community was much further behind than the straight community when it came to basic civil rights kind of things.

Zandra: Certain people were, needed to show like two or three picture IDs.

Deborah: Three picture IDs.

Zandra: Now, how many people carry three picture IDs?

Deborah: Give me a fuckin’ break. No open-toed shoes.

Eric: That’s because you were Black.

Zandra: It wasn’t—they never said that…

Deborah: Arbitrary.

Zandra: Yeah, they never said that, but everybody that was people of color would get carded, you know, heavily.

Deborah: Yeah, so if I went with a white friend, maybe I wouldn’t make it in the door and they would. You know, that kind of stuff.

Eric: They really had a designated night when Black people could come?

Deborah: Yes! I’m telling you.

Eric: Did they advertise it as such?

Deborah: The way they would advertise it would be through the entertainment. Like a Black DJ or Black music or some kind of like connotation that it was gonna be like more that kind of culture was that day.

Eric: Then you wouldn’t be carded three times.

Deborah: I’m telling you, that was the biggest joke. Plantation night.

Eric: Did it make you crazy?

Zandra: It’s terrible.

Deborah: Beyond, I mean, beyond crazy. Just, how fucking dare you? Who the shit do you think you are? I mean, just, really, who do you think you are? You know, you’ve got to realize, too, that like we’re both women of color. And you cannot separate that, you just can’t, you know, separate like our lesbianism from our racial identities. So we’re in this really high consciousness stuff. I mean, up against all kind of stuff, and then we come to the gay and lesbian community naively, expecting it to be more sensitive.

Zandra: How can an oppressed group oppress other people?

Deborah: And what I kept getting over and over and over again was that people of color didn’t matter and that we were somehow real ancillary. It’s like white was right and just racial comments, just racial slurs.

Eric: People would say things.

Deborah: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. I mean, like, all of the time. All of the time. And then out of my own need, feeling ostracized, round about 21, 22, I started a big social club network thing for Black lesbians, about 600 women. And actually I met Zandy through that.

Eric: A social group for lesbians. And you walked through the door?

Zandra: They had a party at this club. I remember walking in and seeing her at the bar and thinking to myself, “Goddamn, perfect.” And then meeting her and realizing, “Oh, I am going to get in trouble with this woman. Somehow, somewhere, sometime, I will definitely get in trouble with this woman.”

Eric: Let’s lead up to the restaurant. Why did you make the reservation?

[Phone rings.]

Zandra: Sorry.

Eric: You hadn’t planned to make any political statement by going to dinner.

Deborah & Zandra: No. Oh hell, no.

Zandra: It was the first time…

Deborah: Privacy.

Zandra: It was the first weekend… At the time I was working on Saturdays. So this was the first weekend that we were gonna have a complete weekend together since we had gotten together. It was also the year right before the Martin Luther King’s birthday was made into a holiday. So it was the first real weekend that we were gonna to have together.

Deborah: So we were gonna take off Friday. His birthday was on the 15th, a Saturday, and we were going to take Friday off. So this was for Thursday night, the 13th of January. ‘Cause see we were gonna have this three-day weekend.

Eric: 1983.

Deborah: Of 1983.

Zandra: And a friend of mine told me about this restaurant that was really nice. And the restaurant had these six booths on one side that were real romantic, and little sheer curtain and it was just perfect.

Eric: And what was the name of the restaurant?

Deborah & Zandra: Papa Choux.

Zandra: So I made the reservations. And at this time Deborah didn’t know where we were going so it was going to be a surprise to her. And we got to the restaurant they… and I had requested the booths. We got there and…

Eric: The reservation was in your name…

Zandra: Yes, the maitre d’, or the person that we thought was the maitre d’—later on we find out that he wasn’t the maitre d’—was a waiter, kind of questioned us about, “Are you sure you want the booths?” And we told him, yes, that’s what…. Deborah didn’t know what we wanted because she didn’t…

Deborah: I said we wanted the booths. Yes, we wanted the booth.

Zandra: So they showed us to the table. And it’s the type of restaurant, or the booths where you have to move the table out so that you can get in.

Deborah: It was like a horse shoe.

Zandra: Yeah, it was like a horse shoe. And in the middle of the horseshoe was, was like a fountain and there was a guy with… a violinist who came around. And the booths… right in front of the table was a little white sheer curtain that closed. And the candle light. And it was just romantic.

Eric: Did it occur to you that this might be a problem?

Zandra: Not at all.

Eric: Didn’t cross your mind.

Zandra: Not at all. I mean, to me, discrimination never enters my mind first, ever.

Eric: You didn’t feel funny making reservations…

Zandra: No.

Deborah: We don’t ghettoize ourselves like that. We don’t ghettoize ourselves. The world is what we live in.

Zandra: They showed us to our table. We sit down.

Deborah: And we were waiting for the menus. We were there like three minutes, which is like a decent amount of time—three to five minutes. And the same guy came back and yanked the table away and told us, you know, “So sorry, you know, but you can’t sit here.” You know, and that’s when he went into all this bullshit about, “It’s against the law…”

Zandra: “It’s against the law,” and, you know…

Deborah: “… to serve two men or two women in these booths.” And that’s when we explained to him that we had been activists for a very long time and that, that’s bullshit. That if I can get a motel room with this woman, I know I can eat with her. That’s what we told him. We said, “I don’t know what, you know… you on drugs? I mean, what is the problem?”

Zandra: And of course, at that point it was, you know, everybody is looking out of their little booths. And we started… We asked to see the manager and…

Deborah: We weren’t gonna move.

Zandra: Oh, and the manager came… the guy that turned out to be the real maitre d’ and not the manager. We thought we were talking to the manager. He kept giving us the back-of-the-bus type of thing. You know, “Well you can sit over there. And you can sit over here and you can have free drinks.” The whole thing. “But you will not… you cannot sit here. You will not be served here.” And kept insisting that it was against the law, it was against the law. And we kept saying, that’s bullshit.

Deborah: And, you know, that really makes me crazy thinking about it. You know, that made me more mad. So you gotta remember, we were there about Martin Luther King’s birthday and we were going to take it off the next day as this real show of solidarity and its importance and the whole bit. And if there’s anything that King had taught us, it was that we could sit anywhere in the restaurant we wanted to sit. And he kept saying it was for couples.

Zandra: Oh, yeah, for couples only.

Deborah: Only. And we said, “A couple of what?”

Zandra: We’re a couple.

Deborah: Then he started copping out on the owner. He said the owner was adamant…

Zandra: We took everybody’s name.

Deborah: … that no two men and no two women were going to be served there. So this is like going on for about 15 minutes now, you know. We’re not budging and we were screaming at each other. And, I mean, he looked at us like, you know, “You can rot and freeze your ass over in hell, you know. We will serve you some place else, but this section is for other kinds of people than you.”

Eric: Did he have any idea who he was talking to?

Zandra: No.

Deborah: Nah, I don’t think so.

Zandra: We left fuming, and taking everybody’s name, just fuming.

Deborah: You know, I think she was more angry than I, even as angry as I was.

Zandra: Fuming, I have never, ever, ever been denied blatantly anything because of who I was, ever. You know, I knew about, you know, the discrimination that went on. My grandfather was discriminated in the same way that Blacks were discriminated, where it was segregated and segregated meant white and others, you know. So I had heard about the discrimination that my grandfather had to go through and… But never did it happen, never did it happen to me. And I had never been told that I couldn’t do something or have something or be somewhere or because of who I was or the color of my skin. And I… How dare you! How dare you!

Deborah: It fucked with her date.

To summarize it quickly… Yeah, what happened. Okay, we go to court. The lower courts rule against us. The appellate court rules for us. So they have a right to petition the Supreme Court, which they did. When the Supreme Court said they weren’t going to hear it, then that meant that the next lowest level, the appellate court’s, ruling was going to stand.

There’s like a four- or five-day window in between the appellate court finding out that the Supreme Court is not going to hear and then following through with what they started to do in the first place. In that window they closed down and had all of these ads and had this public wake and everything else. So it’s like, rather than be—rather than serve us and comply with the law, they just closed the booths. They said, “Fuck you,” you know, “we’re not going to do it at all.” So they had a public wake—you know, the cameras, the 11 o’clock news, and the whole bit. Free drinks. “True romantic dining died on this day.” Ads out.

Zandra: Yeah, it was terrible.

Eric: Disgusting.

Deborah: Yeah, and they closed it.

Zandra: They, they from the very beginning, put the… put the boxing gloves on. I mean, their intent was, we’re gonna fight you to the very end, which is what we ended up doing.

Eric: So that was the end of the booths.

Zandra: That was the end of the booths. That was the end of the booths.

Deborah: Well, basically, yeah, because we went back and they, you know, issued the injunction and they issued, you know, the motion of summary of judgement. We won and they paid the attorney’s fees and gave us our fine, $250 a piece, which was the fine for the local ordinance.

Zandra: They had to pay the attorney’s fees, which was…

Deborah: …almost $30,000.

Zandra: Yeah…

Deborah: Yeah, almost $30,000. So they closed the booths. It’s kinda like what they did in Mississippi and Alabama. You know, instead of lettin’ the Black kids swim in the public pools, they just closed the pool.

Eric: Pull the white kids out of the public schools and start an academy.

Deborah: Yeah, that’s what they did. They just closed it.

Eric: Was it worth it?

Zandra & Deborah: Oh, yes. Oh, hell yeah.

———

Deborah Johnson and Zandra Rolón Amato never set out to test anti-discrimination laws, but they did and they won. And even though the owner of the Papa Choux restaurant simply carted his romantic booths to the curb, Deborah and Zandra’s case put teeth into the local gay rights ordinance. While their case didn’t actually change California’s civil rights bill to add sexual orientation, the appellate court interpreted the law to include sexual orientation. Also, their high-profile court challenge made national news and showed the impact of prejudice on ordinary citizens who were simply trying to live their lives.

Deborah and Zandra separated in the mid-1990s. I called each of them just the other day to see how they were doing and to ask them about their moment in history.

Dr. Zandra Rolón Amato is a chiropractor in private practice. She told me the experience of the Papa Choux case and the media attention that followed has allowed her to be fully engaged in her life as a lesbian and proud of it.

The Reverend Deborah Johnson is the founder and spiritual director of Inner Light Ministries in Santa Cruz, California—a 2,500-member spiritual community.

Deborah said that her favorite memory from that time was hearing their attorney, Gloria Allred, in an on-air radio debate with Papa Choux’s attorney. In his attempt to claim that what the restaurant did wasn’t discrimination against gay people, he said the restaurant staff didn’t know that Deborah and Zandra were lesbians because they were dressed so nicely. Yeah, right, and all gay men love Broadway show tunes. Well, anyway…

———

Making Gay History is a team effort. Thank you to executive producer Sara Burningham and audio engineer, Anne Pope. We had assistance from Josh Gwynn. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers. Thank you, also, to social media strategist Will Coley, our webmaster, Jonathan Dozier-Ezell, researchers Bronwen Pardes and Zachary Seltzer, and thank you to our intrepid photo editor, Michael Green. A very special thank you to our guardian angel Jenna Weiss-Berman.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season three of this podcast is made possible with funding from the Ford Foundation, which is on the front lines of social change worldwide.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, NPR One or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also go to makinggayhistory.com. That’s where you’ll find all our episodes, including photographs, notes, and links to additional information about all the people we feature in Making Gay History.

So long! Until next time!

###